1.

A kindling sense of apocalypse is business as usual for Californians, who live almost nonchalantly with impending doom. Wildfires eat up the landscape, roar into the cities, drop tons of choking ash in the mountain-locked valleys. Mudslides come in winter and spring. Underfoot is the constant threat of “the big one,” the earthquake that will end everything in a few minutes. Dwindling rivers, drained lakes, and recurring droughts keep the southern and most populous part of California in a state of anxious thirst. The most recent drought lasted from 2011 to 2017, and 2011–2015 was the driest period since record-keeping began in 1895.

Yet quotidian life hums on. “There’s no explanation for it, but we feel immune,” a wealthy Angeleno told me. California’s gross economic output is almost $3 trillion, which, were it a sovereign nation, would make it the fifth-largest economy in the world. Today the Republic of California, as a couple of dozen settlers christened it in 1846 during the Mexican-American War, again feels like a breakaway state, with its own mores, laws, phobias, and monumental contradictions.

The California legislature’s rebellion against President Trump’s polices may be the most serious one that an individual state has mounted against the federal government since South Carolina threatened to secede over cotton tariffs in the 1830s. (California’s present-day secessionist movement, called Calexit, has little popular support. Californians don’t see themselves as separate from America but as its epitome, “the keeper of its future,” in the words of its highest elected officials.) The terms of the rebellion were set on November 9, 2016, the day after Trump won the presidency, when the heads of the state senate and assembly issued a joint statement declaring that California “would lead the resistance to any effort that would shred our social fabric or our Constitution.”

“Resistance” has become an overused word, but state lawmakers have made good on their vow. The California Values Act, or sanctuary law as it is popularly known, restricts cooperation between local police and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which has become, in California and elsewhere, a roving deportation force with something resembling paramilitary powers.1 The Justice Department has sued California over the law, and last March then attorney general Jeff Sessions traveled to Sacramento to encourage a gathering of California’s Peace Officers’ Association to “stop actively obstructing federal law enforcement” and “protecting law breakers” at the behest of “the most radical extremists.” Sessions got a polite but far from enthusiastic reception. Most local police have enforced the sanctuary law. Some, like Sheriff Donny Youngblood of Kern County, at the southern end of the Central Valley, where thousands of undocumented farmworkers reside, have openly defied it and given ICE free rein. Youngblood has deemed Bakersfield, the county seat whose population is 50.5 percent Hispanic, a “law and order city,” not a sanctuary. The city of Los Alamitos in Orange County passed an ordinance that exempts it from the sanctuary law. Other localities have contemplated doing the same.

The Justice Department lawsuit is only one of many that the federal government has filed against California since Trump took office. The state prohibits employers from granting immigration officers entry to workplaces in order to verify the legal status of employees without cause, another point of contention. ICE officers haunt courtrooms, grocery stores, bars, housing complexes, and school parking lots, trawling for immigrants who have worked in California for decades and creating, a restaurant employee in Fresno told me, the feeling that “we are being hunted the minute we step out of our homes.” With every new court ruling the legal landscape changes, leaving immigrants unsure of their legal status. Meanwhile, ICE intensifies its push into their lives, insisting that California’s sanctuary law has forced it to invade communities where “illegals” reside, and that if an atmosphere of fear has set in, it’s the state’s fault, not ICE’s.

With equal defiance, California has strengthened its carbon emissions laws in response to the EPA’s rollback of the Clean Air Act, fuel efficiency standards, and other environmental regulations. Every new home built in the state is required to have solar panels, and in September Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill that would make California’s electricity grid 100 percent carbon-neutral by 2045. In addition, the legislature has passed the country’s strictest net neutrality law, a strike against the FCC’s nullification of Obama-era regulations. These are more than token actions. California is the nation’s biggest consumer of automobiles and other manufactured goods. Its laws influence, and sometimes dictate, the way consumer products are made across the US.

All of these efforts have turned California into the repository of many liberals’ hopes of rescuing America from the ravages of Trump. But how realistic are such hopes? If rescue means regaining a Democratic majority in the US House of Representatives, then California has done its part. In an astonishing turn of events even for this bluest of states, all seven congressional seats held by Republicans in districts that Hillary Clinton carried in 2016 went Democratic in the 2018 midterms. These included two seats in the San Joaquin Valley, one of the most conservative parts of the state, where Jeff Denham and David Valadao, both relatively moderate Republicans, were narrowly defeated. (Valadao lost by 529 votes in the 21st District, the last race in the US to be called.) In Orange County, birthplace of the John Birch Society and Richard Nixon, Democrats now hold every congressional seat, some of them in districts a Democrat had never won. Only seven of the state’s fifty-three congressional seats are now held by Republicans. (It’s worth noting that Kevin McCarthy, the House Minority Leader, and Devin Nunes, former chairman of the House Intelligence Committee—both Californians and two of the most fanatical Trumpists in Congress—were reelected.) Today only 25.3 percent of registered voters in California are Republicans, a new low.

Advertisement

If, on the other hand, rescue means lifting the country out of a deepening abyss where the bottom 60 percent of households owns just 2 percent of total wealth and more Americans scramble for a living wage, then California offers little hope. When housing costs are factored in, it has the highest poverty rate in the US. More than a quarter of the nation’s homeless live in California, and encampments of the destitute are a part of the landscape in almost every major city and in many towns.

As I traveled through the state recently, housing, not Trump, was the main subject on people’s minds. Lawmakers seem paralyzed in the face of the country’s most dire housing emergency. Local municipalities have no power to regulate their own housing stock: a 1995 law allows landlords across the state to raise rents to whatever the market will bear when a tenant moves out. The real estate lobby is so powerful that a liberal Democratic legislature has repeatedly declined to overturn or even reform the law. A ballot initiative to repeal it, known as Proposition 10, was defeated by more than twenty percentage points on November 6. Both Gavin Newsom and John Cox, the Democratic and Republican candidates for governor, opposed it, on the grounds that stabilized rents would discourage new construction—by potentially reducing profits—and exacerbate the housing shortage. There is no conclusive evidence that this is true—New York City, with about one million rent-stabilized apartments, has plenty of development.

At the same time, in most localities homeowners have tight control over their neighborhoods and reject proposals for moderately priced multi-unit buildings. The standard liberal objection is that greater housing density will increase traffic and air pollution and overload fragile public schools. The school system was a victim of Proposition 13, a homeowners’ revolt in 1978 that froze property taxes—the primary source of school funding—for both commercial and residential real estate. Prior to its passage, California had one of the finest public school systems in the country and was ranked as high as fifth among all states in spending per pupil. By 2009 its rank had fallen to forty-seventh. Proposition 13 discourages people from selling their homes, since a change in ownership results in a much higher valuation for taxes. This in turn contributes to a “lack of product,” as realtors call it, driving up prices. In the second quarter of 2018, the median price for a home in California was $597,000, beyond the reach of three out of four residents.

Nimbyism among most homeowners has become an automatic posture in California, a residue of the slow-growth movement of the 1980s and 1990s, which sought to curb the excesses of developers who pounced on every valuable swath of land with thoughtless, often environmentally destructive projects. Conservation and development don’t have to be at odds, but over the years conservation has devolved into a blunt, socially acceptable instrument for limiting the construction of affordable housing. In a perversion of governmental regulatory intentions, arcane provisions in the California Environmental Quality Act of 1970 are used by homeowners in cities to block high-density development that would reduce pollution and help alleviate the housing crisis. Partly as a result, a unit of affordable housing cost $425,000 to build in 2016, the highest in the country.

For California to meet its antipollution targets it will have to allow the construction of more apartment buildings, especially in areas near mass transit lines where residents wouldn’t need cars. But in April, a bill that would give the state the power to override local zoning laws and approve buildings four to five stories tall near transit lines was squashed in the legislature before it reached the floor. Debate about the bill exposed California’s split psyche, torn between the myth of the self-reliant Far West and the challenge of social emergencies that only the government can solve. On the campaign trail, Newsom made it clear that he wouldn’t sign the bill if it were passed, though he has promised to build 3.5 million new homes by 2025. (A revised version of the bill is being introduced, this time with the support of Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti. Governor-elect Newsom has yet to endorse it, and its fate is unknown.)

Advertisement

Housing pressures from Silicon Valley ripple outward in every direction. In 2017 the median salary at Facebook was $240,000 a year; at Google it was around $200,000. Nevertheless, many of these employees have resigned themselves to a two-hour commute in order to find living quarters they can afford, pushing up prices in Oakland to the north, Salinas to the south, and across the Coast Ranges as far east as Sacramento and Fresno. Meanwhile, the homeless colonize almost every public space: under freeways, in parks, in private lots whose chain-link fences have been cut and bent open. Pup tents and ripped plastic tarps are everywhere. Thousands more live out of cars or RVs parked on the street. In a considerate act that nevertheless seemed to acknowledge the government’s impotence, Oakland mayor Libby Schaff put up sheds and a central toilet facility in a parking lot near a freeway. In Berkeley I met a public school teacher who was living in her Honda. I was surprised to see virtually no new construction in Berkeley, despite the fact that everyone I talked to, homeowner or not, bemoaned the ruinously high cost of housing. In Salinas, 110 miles south of San Francisco, I visited a two-bedroom apartment with thirty adults and children living in it, the adults sharing the rent, almost all of them with jobs.

In Southern California the situation is no better. Los Angeles, with a population of four million, has 53,000 homeless; Angelenos routinely refer to their city as “the homeless capital of America.” Thousands more live in garages, campgrounds, and makeshift shanties in private backyards. In Orange County rundown motels on the edges of cities and towns are crowded with working families paying week to week for their rooms. Disneyland in Anaheim is the largest employer in Orange County, with 30,000 “cast members,” as its hair stylists, costumers, custodians, puppeteers, candy makers, ticket takers, security guards, and hotel and food service workers are called. A recent survey of Disneyland employees found that “two-thirds meet the department of agriculture’s definition of ‘food insecure’; fifty-six percent are worried about being evicted from their homes or apartments,” and 11 percent reported being homeless at some point in the last two years.2 This invisible homelessness—people living not on the street but without a fixed shelter or address—stretches throughout Orange County: a professor at the University of California at Irvine (UCI) told me that at least 10 percent of his students sleep in their cars.

2.

Irvine, with a population of 275,000, is a flawless expression of California’s exclusionary property laws and the nearly absolute power of its largest landholders and developers. The city wasn’t shaped by restrictions imposed by the Nimbyism of individual homeowners, as in the Bay Area and Los Angeles County, but rather by a single vast corporate entity. Irvine was built on land owned by the Irvine family, originally known as the Irvine Ranch. James Irvine, a Scotch-Irish immigrant, accumulated the holding—a remote, drought-stricken 93,000 acres—between 1864 and 1868 with money he made selling supplies to gold prospectors from a store in San Francisco. It was still intact in 1960, when the Irvine family hired the architect William Pereira to design the core of the city on 10,000 acres and plan the development of 80,000 acres around it. The holding hasn’t been broken up; today it is owned solely by Donald Bren, who acquired it from the Irvines in 1977.

Irvine may be the most fully realized vision we have of a large private city—planned, paved, and spotless. It isn’t so much governed as managed, a real estate venture rather than a municipal entity. It is not a bedroom community. It has set itself up as a mixed-use business center, able to provide its residents with jobs. Toshiba, Allergan, Broadcom, Western Digital, Gateway, and Taco Bell, to name a few, have their corporate headquarters there. Pools of water along the parkways soothe drivers’ sun-fried eyes. Office parks and high-rises are, almost without exception, clad in black metal, gray concrete, and reflective glass.

In 2006 the median rent in Irvine was higher than that in any city of more than 100,000 in the country. When the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis hit, houses there kept their value. When its highly regarded school system faces a budget cut, Bren writes a check to cover the shortfall. A modest “starter” house can be bought for $729,000. I visited one for sale in a predominantly Asian neighborhood, a beige stucco structure that conformed to Bren’s insistence on Mission Style architecture. The realtor had me put plastic covers over my shoes before entering; as I inspected the property, she busied herself with catching a fly that had invaded the house. A middling house in a gated neighborhood can be bought for $2.3 million. The realtor who showed me one proudly described himself as “half Anglo, half Vietnamese.” He pointed up a hill where, about a mile away, another “community” was under construction, with houses going for $6 million. “Prices keep going up,” he said. “A lot of Chinese are coming, new arrivals, and they pay all in cash.”

Kia Hamadanchy, a thirty-two-year-old Irvine native, told me, “There’s no real poverty in Irvine. Poverty isn’t allowed. If a homeless person is spotted, the police are called, they pick the person up, drive him to Santa Ana,” a majority-Hispanic city seven miles to the north, “and drop him off.” (The homeless students at UCI live in other parts of Orange County.) Irvine is consistently ranked the first- or second-safest city in the country. “But,” Hamadanchy said, “everyone is obsessed with crime,” as if their security were so precarious it could be shattered at any moment.

Hamadanchy graduated from University of Michigan Law School “at the worst time, during the 2008 recession,” and worked in Washington, D.C., for Senator Tom Harkin, and then for Senator Sherrod Brown. He came back to Irvine to run for Congress in 2018, as a Democrat, and was one of four losing candidates in the so-called jungle primary—the top two candidates advance to the general election, regardless of party—on June 5 for the 45th District. His parents immigrated to the US from Iran, and he said that during the campaign

people told me I needed a Starbucks name, like Ted or Brett. They tell this to everyone of Middle Eastern descent. There’s never been an Iranian elected to office in Orange County. Iranians don’t vote. They’re too cynical about politics because of what they experienced in Iran.

The 45th District had never sent a Democrat to Congress, but Clinton carried it in 2016. Mimi Walters, the Republican incumbent, was seen as vulnerable this year for voting to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017. Shortly after the election, she was declared the winner by three percentage points, the outcome most observers had expected (she had won by seventeen points in 2016). Her Democratic opponent, Katie Porter, a protégé of Elizabeth Warren who was considered too liberal for the district, had won only 20 percent of the primary vote. Even more discouraging for Porter’s chances was the fact that in the primary only 13 percent of eligible voters showed up at the polls. But when mailed ballots were counted after the November election, Porter scored a major upset. Irvine, the largest city in the district, is now 45 percent Asian, and in California 68 percent of Asians disapprove of Trump. The racism that drives his anti-immigration rhetoric appears to have helped Porter win.

Hamadanchy is wry about growing up in Irvine, though his affection for the city is obvious. As a boy, he and his friends would hang out at a vast outdoor shopping environment—one hesitates to describe it merely as a mall—called the Spectrum Center. It is designed to resemble a perfect American village, like the stage-set town in the movie The Truman Show. The brick-and-tile streets wind pleasantly through a city of shops, with a rectangular commons planted with artificial turf and a Ferris wheel. The commons is crowded with shoppers, their children eating ice cream or racing across the turf. Loitering is encouraged: wicker chairs, round brass tables, and umbrellas appear on one “street”; on another street unraveled bolts of cloth are strung tautly overhead to give shade. One wanders through different architectural motifs and facades, an artificiality so complete, so thought-out in every detail, that it feels like a performance. It is the Irvine Company’s masterpiece, a perfect consumerist dream.

3.

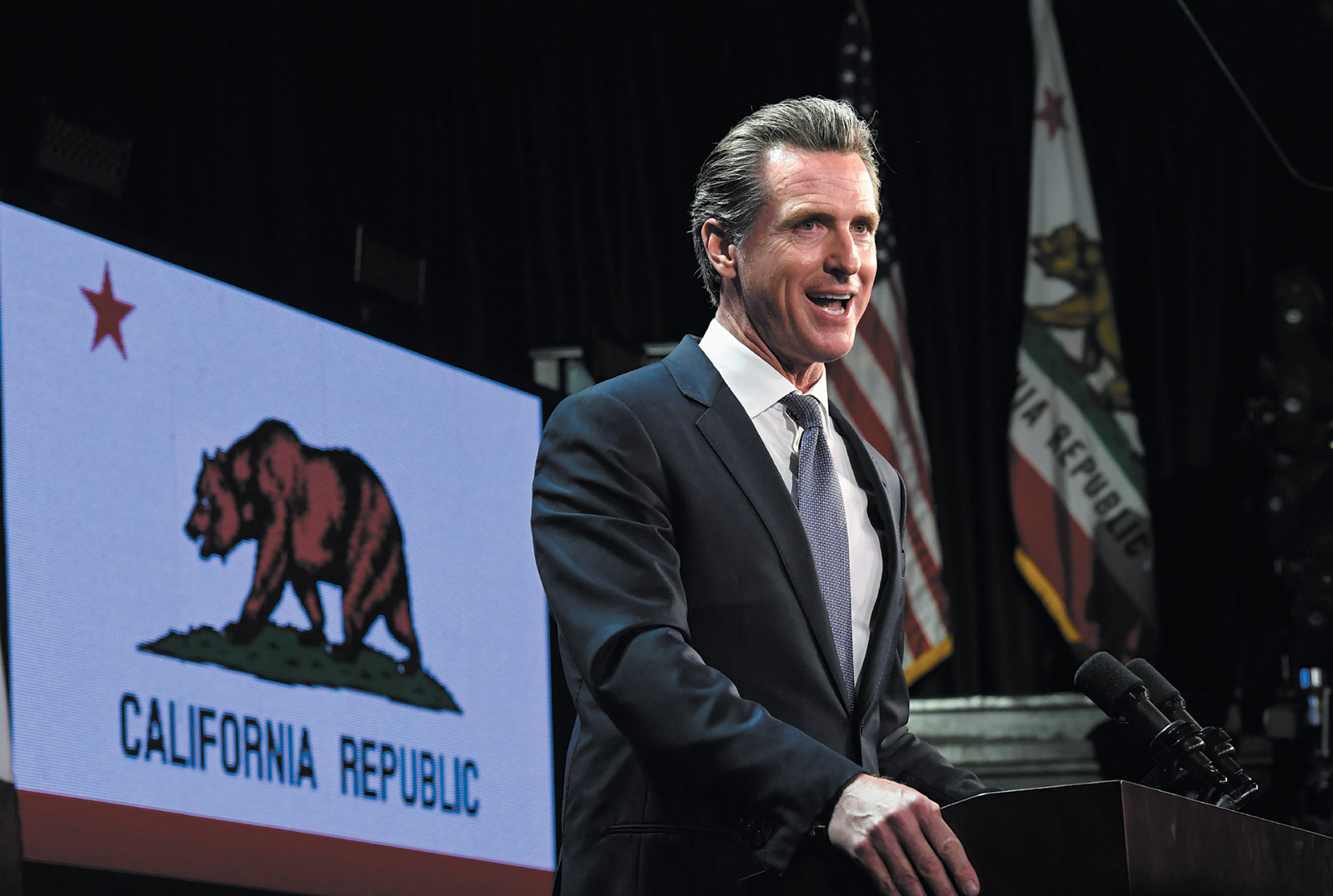

Gavin Newsom, who won the race to succeed Jerry Brown as governor (and “head of the California resistance,” as a New Yorker headline called him) with 61.9 percent of the vote, is a typical Bay Area Democrat: socially and environmentally progressive, with a Machiavellian allegiance to developers and large landholders who have been the major force in state politics since the Gold Rush. “You can’t run for statewide office without money from developers,” Peter Dreier, a professor of politics at Occidental College, told me. There is scant hope that Newsom will be able to put a dent in the state’s problems, especially when it comes to housing. Since his bold defense of same-sex marriage as mayor of San Francisco in 2004, he has been a cautious politician, a self-described “passionate free-enterprise Democrat” who drapes himself in fashionable social justice platitudes. He will continue California’s fight against Trump’s immigration and carbon emissions policies, but it’s difficult to imagine him backing reforms that would put his political career on the line.

Google, Apple, Netflix, Facebook, and the other behemoths of Silicon Valley that are the chief source of California’s enormous wealth have benefited extravagantly from Trump’s corporate tax cuts—particularly the provision that lowered the tax rate on corporate cash repatriated from overseas. There is little evidence that top executives at these companies are displeased with the Republican regime in Washington. California’s tech billionaires have shown a preference for dramatic acts of personal philanthropy over political donations, the more traditional way of parlaying wealth into influence. They have cultivated the image of benevolent lords with the power to replace the usual functions of government. An example of this is Marc Benioff, the founder of Salesforce, a cloud computing service based in San Francisco. Benioff makes large contributions to public schools and hospitals that would fail without him, in effect paying out of his pocket for basic services that government cannot—or will not—provide. But donations are dependent on the philanthropist’s whim—should things go sour, they can be discontinued in the blink of an eye.

Because of Proposition 13’s property tax freeze forty years ago, 70 percent of California’s budget, which for 2018–2019 totals just over $200 billion in spending, depends on personal income taxes, 46 percent of which are paid by the wealthiest 1 percent. To illustrate the state’s precarious reliance on its richest residents, a single zip code in the town of Palo Alto, where Mark Zuckerberg, Google co-founder Larry Page, and Apple CEO Tim Cook live, accounted for nearly $1 billion in state taxes in 2016. A bad year in the stock market, with reduced capital gains, could lead to a deficit, even if the overall economy does well. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, a mild recession would result in a $20 billion deficit; a moderate recession would cut revenues by $80 billion and leave the state $40 billion in the red.3

Funds for affordable housing, health care, and education would be slashed just when the state needs them most. The vulnerability of a huge swath of California’s population is acute—in addition to those already living in poverty, millions more are what social workers call “one event away” from destitution. A substantial increase in homelessness is almost unimaginable because it is already so widespread, but it could easily happen.

California has a history of turning sharply to the right during hard economic times. In 1994, after defense industry jobs vanished with the end of the cold war and the state descended into a protracted recession that included a real estate crisis and the collapse of local banks, voters passed Proposition 187. That initiative, promoted with the slogan Save Our State (S.O.S.), blocked undocumented immigrants from access to health care, education, and other state services. Fifty-nine percent of the electorate voted for it. Republican governor Pete Wilson rode the anti-immigrant wave to reelection, then ordered state and local employees to report suspected “illegals” to the state attorney general. Although it was struck down by the courts and eventually led large numbers of Californians to abandon the Republican Party, Proposition 187 has provided a roadmap for the Trump administration’s anti-immigration policies.

Like the rest of the US, California is in a pernicious trend of steady GDP growth and low unemployment accompanied by the amassing of wealth and power by the few and intractable poverty for the many—the result less of joblessness than of the increase in minimum-wage service jobs, as well as the high cost of housing. A recent article in The Economist points out that the state’s GDP rose 78 percent in real terms between 1997 and 2017, and “the number of people with jobs has grown almost without interruption since 2011.” At the same time, 45 percent of California’s children are living at or near the poverty line, as defined by the Public Policy Institute of California and the Center on Poverty and Inequality at Stanford University, which have come up with a measure that takes the cost of living into account. Eighty percent of those below the poverty line live in households with at least one working adult.

As a result of these inequities, America’s richest and most liberal state is also its poorest. Yet Californians have recently demonstrated a willingness to put aside immediate self-interest for the common good. On November 6 voters declined to repeal a statewide gasoline tax that is used to build and maintain roads; and in 2016 Angelenos levied a half-cent sales tax on themselves to fund the most ambitious mass transit expansion in the city’s history.

These initiatives suggest that voters may be inching toward the acceptance of more sweeping reforms—even ones that affect their own pocketbooks. Such reforms would have to begin with an enormous housing initiative with the power to overrule the parochial interests of homeowners and developers; they would also include a change in state rent laws and new conservation regulations that couldn’t be used as a pretext to limit the construction of housing for people of modest means.

California’s politicians say that Proposition 13 is untouchable, but is it? At the very least, voters are likely to support an end to the tax freeze on commercial real estate, which would restore a reliable stream of money for schools and affordable housing. But homeowners who have profited spectacularly from rising property values should also have to contribute. California was once famous for its ability to lift its residents out of poverty. This was partly because of its exemplary education system and partly because of an ever-increasing supply of housing built on seemingly endless tracts of land. Today that model of urban sprawl is rightfully dead. But the state has found no model to replace it. For inspiration officials might look to the city of Minneapolis, which has eliminated single-family zoning in every neighborhood, allowing for three units on plots of land where only one was permitted before.

Numerous studies show that stable, affordable housing is the most important factor in people’s social and economic well-being. California cannot address the most essential needs of its residents if it must always defer to homeowners’ dislike of traffic or less-well-off neighbors. If elected officials have the will to enact reforms that would spread the benefits of the state’s prosperity, California would be more than a symbolic “state of resistance.” It would point the way to a future beyond the dystopian nightmare of haves and have-nots that is now the main threat to America’s democracy.

—This is the second of two articles on California.

This Issue

January 17, 2019

‘Has Any One of Us Wept?’

Between Two Empires

-

1

See my previous article, “In the Valley of Fear,” about undocumented immigrants in the San Joaquin Valley, The New York Review, December 20, 2018. ↩

-

2

See Peter Dreier and Daniel Flaming’s exhaustive survey, “Disneyland’s Workers Are Undervalued, Disrespected, and Underpaid,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 2018. ↩

-

3

See the excellent article by Melanie Mason, “Can California’s Next Governor Fix the State’s Problems? It Depends on Palo Alto,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 2018. ↩