On August 26, 1768, a day of fresh winds and cloudy skies, James Cook guided his ship, the Endeavour, past the coast of Cornwall into the open sea. On board, he noted in his journal, were ninety-four men, “Officers Seamen Gentlemen”—including the wealthy young naturalist Joseph Banks—and the ship carried provisions for a voyage of eighteen months. They were heading for the South Pacific.

Cook led three expeditions to the Pacific, each with an overt scientific aim that marked them as typical Enlightenment projects. The first, from 1768 to 1771, was promoted by the Royal Society, which was keen to send expeditions to Scandinavia, Canada, and the Pacific in order to observe the transit of Venus across the sun and to use the differences in angle among the various locations to calculate the distance of the earth from the sun. In early 1768, before Cook’s departure, the British commander Samuel Wallis returned to England with news of his landing in Tahiti the previous year, and the island was chosen as the expedition’s base. Cook sailed west, via Brazil and Tierra del Fuego, and across to Tahiti. From there he would sail on to New Zealand and the uncharted east coast of Australia, and back through Indonesia.

The second voyage, from 1772 to 1775, was sponsored by the Admiralty to hunt for the elusive Great Southern Continent, which the Scottish cartographer Alexander Dalrymple had argued must exist “to counterpoize the land on the North, and to maintain the equilibrium necessary for the Earth’s motion.” This time, Cook sailed east in the Resolution, accompanied by the Adventure under Captain Tobias Furneaux until they were separated in Antarctic fogs. From the Cape of Good Hope the expedition looped along the edge of the great ice fields, and Cook then made two Pacific circuits, visiting New Zealand, Tahiti and the Marquesas, the Tonga archipelago, and the New Hebrides. Sailing home across the southern Pacific and the Atlantic, he concluded that he had traversed the Southern Ocean “in such a manner as to leave not the least room for the possibility of there being a continent, unless near the Pole and out of the reach of navigation.”

Another old Admiralty dream—finding a Northwest Passage—prompted Cook’s third expedition in 1776. In contrast to earlier quests, which approached North America from the Atlantic, he was to attempt this from the Pacific coast, hunting for rivers and inlets that might lead east toward Hudson’s Bay. Unsuccessful, he returned to New Zealand, Tonga, and Tahiti, before heading north and reaching Hawaii in January 1778—the first European landing. From there he crossed to Nootka Sound, off Vancouver Island, and Alaska, twisting through the Bering Straits into the Arctic, before sailing south for the winter, visiting the islands off Siberia and returning to Hawaii on November 26, 1778.

For two centuries Cook was regarded in Britain as a hero of imperial expansion, while in Australia and New Zealand he was seen as a founding father, commemorated in statues and street names, and celebrated on postage stamps. Evoking the late 1930s in a Sydney girls’ school in her novel The Transit of Venus, Shirley Hazzard wrote dryly, “Australian History, given once a week only, was easily contained in a small book, dun-coloured as the scenes described. Presided over at its briefly pristine birth by Captain Cook (gold-laced, white-wigged, and back to back in the illustrations with Sir Joseph Banks).” Reaction against this view developed after World War II. An important turning point came at the 1970 bicentennial celebrations of Cook’s landing at Botany Bay, just south of Sydney, when Aboriginal protesters laid wreaths in the water, remembering those killed during British colonization.

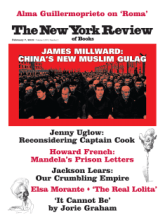

To mark the 250th anniversary of Cook’s departure on his first voyage in 1768, the Folio Society has reissued his journals in a fine three-volume set, bound in the pale azure of a coral-island lagoon, with color plates and a facsimile of the elegant map from the 1794 edition. The text is that of Philip Edwards’s 1999 selection, taken from the monumental four-volume edition prepared from Cook’s manuscripts by John Cawte Beaglehole and published between 1955 and 1967. The use of an existing text follows the Folio Society’s practice of issuing classic works in luxurious editions, but sadly there is no new introduction and no additions to “Further Reading,” a frustrating lack, since new scholarship abounds. Beaglehole’s edition was criticized for omitting much of the violence of Cook’s encounters with indigenous peoples and his dealings with critics at home, and in recent years his voyages have been reconsidered in the light of postcolonial studies.1 More recently, work by leading historians and anthropologists like Anne Salmond in New Zealand has clarified the exchanges between Cook and other Europeans and the people of the Pacific.2

Advertisement

Cook’s account—a mix of spontaneity and anxious revision—gives us his eighteenth-century British perspective, but for other approaches one must turn elsewhere. James Cook: The Voyages, for example, published to accompany an exhibition at the British Library last summer, acknowledges the contested interpretations of Cook’s journeys, setting his account alongside those from the journals of Banks and others who joined his voyages, bringing out buried voices and recognizing the counternarratives of indigenous peoples. Superbly illustrated with images from the British Library’s collection, it is also supplemented by short essays on the library’s website that show, in another twist, how scholars from the South Pacific, Oceania, and Polynesia are now turning back to the journals, drawings, and paintings from the voyages as invaluable sources for the history of dress and tattoos, canoes and dwellings, ceremonies and beliefs. Two other new studies of the rich visual material, both published in 2018, are James Taylor’s Picturing the Pacific: Joseph Banks and the Shipboard Artists of Cook and Flinders and Captain Cook and the Pacific: Art, Exploration and Empire by John McAleer and Nigel Rigby, which accompanies an exhibition of the rich collection at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

On April 13, 1769, Cook reached Tahiti. At Fort Venus on June 3, when “not a clowd was to be seen,” he and his colleagues observed the transit of Venus, although, he recorded glumly, “We very distinctly saw an atmosphere or dusky shade round the body of the planet which very much disturbed the times of the contacts.” Nonetheless, the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande would use the data to calculate the distance from the Sun to Earth as 95 million miles (not too far off the actual 92.96 million miles).

Cook, a fine astronomer and mathematician, had been chosen to lead the expedition, at the age of thirty-nine, largely because of his skill as a cartographer. The son of a Yorkshire farmer, at eighteen he was apprenticed to a Whitby ship owner, sailing on the North Sea and the Baltic. Seven years later he joined the Royal Navy, patrolling the North Atlantic, and learned to survey in Canada, charting the St. Lawrence River and the rivers and coasts of Newfoundland. Part of his brief in 1768 was to search for new lands and to survey coastlines. But he was also asked to bring home specimens of minerals, plants, and seeds, and in this he was helped by Banks, who brought with him Daniel Solander—the Swedish pupil of Linnaeus responsible for the natural history collections at the British Museum—and the Scottish artists Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan.

Banks’s team brought back countless skins of mammals and birds, as well as botanical specimens. Botany Bay was named, Cook wrote, on account of “the great quantity of new plants &ca Mr Banks & Dr Solander collected in this place.” The excitement of discovery echoes through Cook’s record of the strange beast seen near the Endeavour River in Far North Queensland in July 1770. It had a small head, neck, and shoulders, but “the tail was nearly as long as the body, thick next the rump and tapering towards the end…its progression is by hoping or jumping 7 or 8 feet at each hop upon its hind legs only…. It bears no sort of resemblance to any European animal I ever saw.” Back in London, the skin of this small kangaroo was stuffed or inflated and it was later painted by George Stubbs, causing widespread amazement.

Scientific research and exploration, however, were always linked to the competition among European nations over trade and territory. Cook had taken with him a sealed set of instructions from the Admiralty, to be followed on leaving Tahiti. These charged him to “observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them,” offering presents and showing “Civility and Regard,” while always remaining wary. Most significant of all, he was told, “You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the name of the King of Great Britain.” In uninhabited lands he should simply “take Possession for his Majesty.”

The notion of “consent” was meaningless without any system of shared values or laws, but Cook cheerfully raised the British flag wherever possible, taking formal possession and marking trees as he left with the ship’s name and the date. In his journal entry for August 23, 1770, at Possession Island off Far Northern Queensland, where he climbed a high hill and saw a clear passage to the west, he wrote that, although he had already taken possession of several places on this coast,

Advertisement

I now once more hoisted English coulers and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third took posession of the whole eastern coast from the above Latitude down to this place by the name of New South Wales, together with all the bays, harbours rivers and islands situate upon the said coast, after which we fired three volleys of small arms which were answerd by the like number from the ship.

In the manuscript that Beaglehole used, “New South Wales” was written later, over a deleted name. Banks, who was with Cook on the hill, makes no mention of the ceremony in his journal. It has recently been argued that this entry is actually a fiction, and that Cook hastily revised it to lay down the British claim when he arrived in Jakarta and heard that Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, crossing the Pacific the year before, had claimed many lands for the French.3 Which would be worse, the flag-raising or the retrospective bluff?

Though instructed by the Admiralty, Cook also listened to the advice of James Douglas, Earl of Morton and president of the Royal Society. While Morton accepted the idea of consent, he anticipated its abuse, pleading that Cook should “restrain the wanton use of Fire Arms” and noting that

shedding the blood of those people is a crime of the highest nature…. They are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit. No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent. Conquest over such people can give no just title; because they could never be the Agressors.

Ignoring the legal argument, Cook took note of the warning against firearms. When the ship’s precious quadrant was stolen in Tahiti, he took hostages rather than use arms, and the quadrant was returned. The guns came out, however, when a musket was stolen, or when threatening crowds surrounded them: in New Zealand, when assailants were undeterred by “peppering with small shott” from Banks and Solander, Cook ordered the ships’ cannon to fire over their heads, “for I avoided killing any one of them as much as possible and for that reason witheld our people from fireing.”

His tactics, could, however, cause violent incidents, like the one that culminated in his death at Kealakekua Bay, on the west coast of Hawaii, on February 15, 1779. Arguments, ably summarized in The Voyages, still surround this incident. Some historians suggest that on Cook’s arrival in 1778, the Hawaiians had believed him to be an incarnation of the god Lono, while other sources claim that he was revered simply as a powerful chief. It was on his second visit that tensions began to rise. When a ship’s cutter disappeared and Cook tried to take the chieftain hostage for its return, two or three thousand people gathered on the shore. The stories are confused, but it seems that as he tried to leave, Cook fired on the crowd but was killed, along with four marines, before he could embark. Sixteen Hawaiians also died that day.

Although constantly baffled by island hierarchies, on all his voyages Cook set out to meet local chieftains and establish an understanding with them, and in this he received invaluable help from individual islanders. The most significant of these was Tupaia, whom he met in Tahiti. A high priest from the nearby island of Ra‘iatea, learned in astronomy, medicine, and navigation, Tupaia was, Cook thought, “a very intelligent person” who knew more of the geography of the islands, “their produce and the religion laws and customs of the inhabitants than any one we had met with.” Hoping to visit England, Tupaia sailed on the Endeavour. A good linguist, he quickly picked up enough English to be able to act as navigator, artist, and interpreter in Polynesia, New Zealand, and Australia; he died of fever, with many others, in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) on the return voyage.

If Tupaia gave crucial assistance, the most famous islander to sail on the expeditions was Omai, or Mai, who joined the Adventure in Huahine, west of Tahiti, in September 1773. In London, under the patronage of Banks and the Earl of Sandwich, Omai became a celebrity, presented to the royal family, dining at the Royal Society, and meeting leading Cambridge scholars. He left England in June 1776, Cook wrote, with a mixture of regret and elation. Remembering his British friends, he was near to tears, “but turn the conversation to his native country and his eyes would sparkle with joy. His behavour on this occasion seemed truely natural.” As Frame and Walker point out in Voyages, the British saw Omai as a model of the Rousseauvian noble savage, whose “natural” simplicity was an implicit criticism of the corruption and artifice of supposedly civilized European life. For Cook, however, he was chiefly a useful intermediary, a guide to local customs and a means of smoothing his expedition’s path in complex encounters.

Following the Admiralty instructions, Cook scrupulously, if confusedly, observed the people, their dress and way of life, and particularly their ceremonies. On his third voyage, when he took part in a ceremony at Tongatapu, joining the celebrants in letting down his hair and baring his torso, a pursed-lipped officer, “not a little surprised,” commented, “I do not pretend to dispute the propriety of Capt Cook’s conduct, but I cannot help thinking he rather let himself down.” Cook’s aim was always to write a clear record in his dry, matter-of-fact prose, but even he gave way to awe on Easter Island, which he reached in March 1774. Gazing at the huge statues by the sea, he wrote, “We could not help wondering how they were set up, indeed if the island was once inhabited by a race of giants of 12 feet high.”

Cook rarely gives moral judgments on the ways of indigenous people. Although he describes as “barbarous” the human sacrifice he witnessed at Tahiti on his third voyage (at a ceremony to ask Oro, the god of war, for assistance in a conflict with the island of Mo’orea), he was more interested in the practical details and the choice of victim. Explaining his own distaste to the chieftain, he was joined by Omai, who told the chief that if he killed a man in this way in England he would be hanged. “On this,” Cook wrote, the chief “balled out ‘Maeno maeno’ (Vile vile) and would not here another word; so that we left him with as great a contempt of our customs as we could possibly have of theirs.”

Britain in the late eighteenth century had plenty of barbarous punishments, and hundreds of crimes were still punishable by execution. The journals remind us that Cook may have understood this well. On his third voyage, possibly ill as some historians believe, he became more erratic and draconian, ordering floggings or cutting off ears as punishments for theft, and even the burning of houses and canoes when a goat was stolen—bursts of violence not hitherto seen under his command.

With regard to other kinds of offenses, Cook’s attitude was more resigned. He had always been troubled, for example, by his crew’s sexual liaisons with local women, though these never drew ferocious punishments. This is a tale of promiscuous exploitation, although Frame and Walker suggest that in the beginning, at least, most of the men were looking for stable relationships with individual women, “who often sought European goods in return.” Grimly, what the women got in return was sexually transmitted disease. By the third voyage, Cook could see the effect. In January 1778, realizing that they were the first Europeans to land in the Hawaiian islands, he issued firm orders that no women were to be allowed on board: “I also forbid all manner of connection with them, and ordered that none who had the veneral upon them should go out of the ships.” Some men, he noted ruefully, concealed their condition, or simply did not care whom they communicated it to. He had already made the same restrictions in the Cook Islands in March 1777, finding to his horror that the disease was already there, spread from other islands, and knowing that his own crews must be responsible: “I as yet knew of no other way they could come by it.”

Even Cook’s surveying held a threat. His and his colleagues’ cartographic brilliance as they made their “running survey” from sightings on a rolling ship, with compass bearings to prominent landmarks and daily calculations of latitude and longitude, is still astounding. As he sailed, Cook named headlands, bays, and rivers, sometimes from geographical features—such as Lowland Bay or White Island—but also in tribute to royal patrons, as in Queen Charlotte’s Sound. Young Nicks Head honored the twelve-year-old Nick Young, who first spotted the headland. But this naming was in itself a claim of possession, erasing local names and the traditions and stories they contained. Most islands in the Pacific have now reverted to their original names, and in Australia and New Zealand the topographical imperialism of naming individual places has been roundly challenged.4 In New Zealand, for example, Kā Huru Manu, a cultural mapping project, includes an online atlas with over one thousand indigenous place-names.

Cook’s one uncontested achievement, as engrossing as any exploit in Patrick O’Brian’s Master and Commander novels, was his seamanship. Among breathtaking passages, my favorites come from the journal of his second voyage, as he crosses and recrosses the Antarctic circle, surrounded by huge ice islands, watching the petrels, shearwaters, and albatross, and hoping for penguins as a sign of land. But perhaps his most striking triumph was his navigation of the Great Barrier Reef. Having repaired the Endeavour, badly damaged after striking the reef on August 12, 1770, Cook climbed a hill and found to his dismay that the reef stretched in both directions as far as he could see. The only way out was through a passage hardly wider than the ship. This improbable escape achieved, on August 16 they were swept again toward the reef, which Cook described as a wall rising from unfathomable depths: “The large waves of the vast ocean meeting with so sudden a resistance make a most terrible surf breaking mountains high.” “A speedy death was all we had to hope for,” Banks wrote. For twenty-four hours the crew battled the tides, until Cook again risked a dash through a narrow channel, swept on by the ebb tide, “gushing like a mill stream.”

As he sailed and landed and sailed on again, Cook left troves of objects for people to find later, as proof that his ships had been there. One of the last was on Kayes Island (now Kayak Island) off Alaska. “At the foot of a tree on a little eminency not far from the shore,” he wrote, “I left a bottle in which was an inscription seting forth the ships names, date &ca and two silver two penny pieces (date 1772).” If The Voyages steers us through the troubled waters of Cook’s legacy, the Folio Society’s blue-bound edition of the Journals is like one of his time capsules, carrying us back to Cook the explorer and navigator, to the surveyor at his charts and the journal writer at his table, and to the great rolling oceans across which he sailed.

-

1

See Rod Edmond, “Killing the God: The Afterlife of Cook’s Death,” in his Representing the South Pacific: Colonial Discourse from Cook to Gauguin (Cambridge University Press, 1997); Remembrance of Pacific Pasts: An Invitation to Remake History, edited by Robert Borofsky (University of Hawaii Press, 2000); and Glyndwr Williams, Captain Cook: Explorations and Reassessments (Boydell, 2004). ↩

-

2

Anne Salmond, Between Worlds: Early Exchanges Between Maori and Europeans, 1773–1815 (University of Hawaii Press, 1998); The Trial of the Cannibal Dog: The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook’s Encounters in the South Seas (Yale University Press, 2004); and Aphrodite’s Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti (University of California Press, 2010). ↩

-

3

See Margaret Cameron-Ash, Lying for the Admiralty: Captain Cook’s Endeavour Voyage (Rosenberg, 2018), pp. 190–197. ↩

-

4

See, for example, Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and Renaming the Australian Landscape, edited by Harold Koch and Luise Hercus (Australian National University Press, 2009). ↩