We live in a golden age of reissues. Every publishing season seems to bring fresh editions from a vital but ignored past: say, Clarice Lispector, who had one book come out last year, or Lucia Berlin, who had two. For readers, republication offers something rare: the possibility of reclaiming history simply by opening a book. The proper response to this is surely celebration. But I can’t help feeling a bit depressed that so many of the cool new writers are dead.

I’ve been particularly interested in the resurgence of midcentury women novelists who share certain characteristics. These women were underappreciated in their own lifetimes. They may have gotten prizes and awards, but they never earned the fame or money of their male peers or, in many cases, their more successful husbands. They distanced themselves from the women’s movement. They were rude in ways that were probably deeply unpleasant for their contemporaries but now translate nicely into witty anecdotes and retorts.

Take Elsa Morante. Like many of the authors who are regularly discovered and rediscovered, Morante never became internationally famous. Her novels are not widely read outside of Italy, unlike those of her husband, Alberto Moravia, or the works of many of the artists she collaborated with over the course of her life, like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Natalia Ginzburg. Her novels are not difficult, but they are also not easy: violent, emotionally tangled, lushly written in a way that often reads in English as more melodramatic than dramatic, and almost overwhelmingly ambitious.

“Elsa was a bit totalitarian,” Moravia said of his wife after her death. A man who had escaped fascism could not have meant that lightly, but it comes across as accurate and sincere. Morante’s novels have the drive of a general ready to obliterate the field. She’s also one of Elena Ferrante’s favorite writers, and the one from whom she derived her pen name. The connection is made very clear by the fact that this new translation of Arturo’s Island is by Ferrante’s translator, Ann Goldstein, and has a quote from Ferrante on the back.

The violence of Morante’s world starts at birth. Adults who pine for their childhood, boys who want to climb back into the womb: the men Morante wrote about experience entering the world as rejection. “I know, in fact, that mine was real weeping, desperate mourning,” Manuel says of his birth in Aracoeli (1982), Morante’s final novel. He “didn’t want to be separated from” his mother. “I must have already known that that first, blood-stained separation of ours would be followed by another, and another, until the last, the most bloody of all. To live means to experience separation.” Later, he describes trying to suckle on his mother’s breast as a child after his younger sister died: “A great pounding of my heart shook me, a mixture of shudders and happiness; I felt like someone diving into the sea for the first time…. This fulfillment, this honeyed taste made me close my eyes as if in sleep.”

For Morante, the tangled entrapment of family wasn’t theoretical. Poverty and cramped quarters made independence early in her life impossible. Her parents had hoped to create a happy household. But on their wedding night her mother, Irma, a schoolteacher with thwarted literary ambitions, discovered that Augusto Morante was impotent. Irma punished her husband by making him sleep in the basement. Elsa and her siblings later came to learn that their real father was someone they had been introduced to as “Uncle Ciccio.” In Woman of Rome: A Life of Elsa Morante (2008), the novelist Lily Tuck describes how Morante’s mother used to wait until everyone was asleep before she went to the bathroom. The home was so small that even the facts of living had to be hidden.

Morante was born in Rome in 1912, though she liked to shave off a few years. She was a brilliant student but didn’t have enough money to stay in school. She found an apartment of her own and supported herself by editing bad academic writing and exchanging sex for money. “Every day my life becomes more stupid, subject to and tormented by physical needs: material and sexual,” she wrote in 1938 in her diary, one of the few private writings that she preserved. What comes across, even in these short snippets, is a hungry singularity of mind, a tunnel vision of ambition and desire. She complained about her longing for men and then dismissed them as distractions: “My spirit is slave to these obscene, little pastimes which give me the feeling of death.”

She met Alberto Moravia in 1937. He later recalled that they “had supper together with some friends, and as I was saying goodnight to her, she slipped the keys of her house into my hand.” During the war they married, then fled to southern Italy. Both worried about being arrested by the Fascists. This period of panic was in many ways the high point of their relationship. The chaos of war seemed to create a greenhouse that allowed the otherwise fragile marriage to thrive. Morante, who throughout her childhood had read stories of heroes and gods, could act bravely and boldly, as a character in a romance or myth might. She crossed occupied Rome to save the manuscript of her first novel, House of Liars, a long and convoluted story of love and disenchantment. Morante and Moravia wandered around the Bay of Naples, he with an owl on his shoulder, she with a Siamese cat on a leash.

Advertisement

Morante could deal with the stress of war. The boredom of peacetime was what she found difficult. “She considered herself, as it were, an angel fallen from heaven into the practical hell of daily living,” Moravia wrote. (Morante herself refused interviews for much of her life and destroyed many of her papers. Biographers are therefore unfortunately reliant on the words of her ex-husband to gloss her own.)

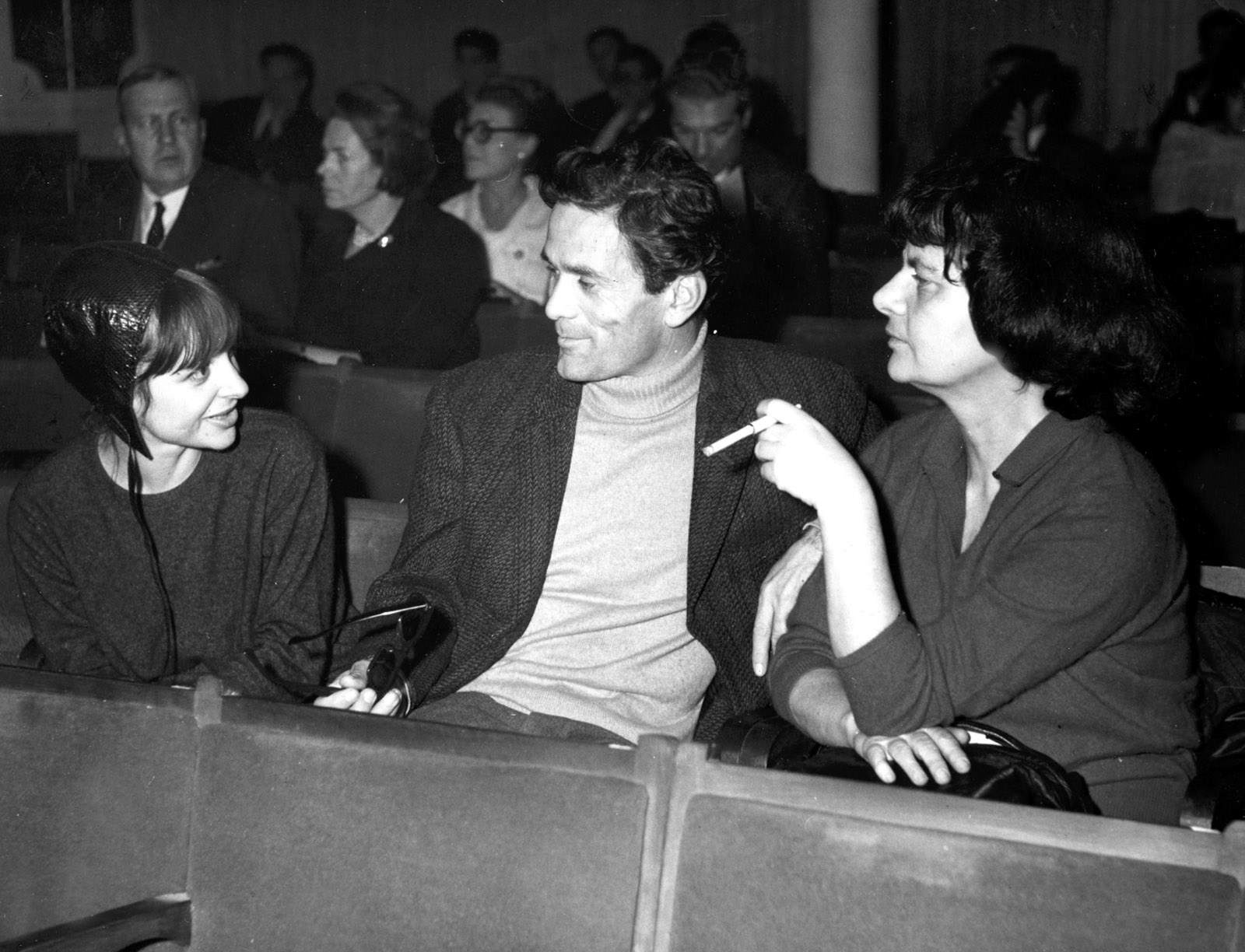

Both Tuck’s biography and Elsa Morante, a French biography by René de Ceccatty, ponder whether Moravia and Morante were the Sartre and Beauvoir of Italy. Like their French counterparts, they were a visible and successful literary couple. They worked on a magazine together and each won many prizes. Morante seemed to enjoy competition with her husband, especially when she won. The translator William Weaver remembers how the only way to get them to come to dinner was to invite Elsa first, then mention that Alberto could also come, if he was available.

From the 1950s, each began to sleep around, Moravia with younger writers (he eventually married one of them, and then another), Morante with a series of men, including the director Luchino Visconti, who were either gay or bisexual and with whom she had tortured relationships. When they separated a decade later, someone told Moravia, “Pity. Morante-Moravia had such a good sound.”

Morante and Moravia each had a Jewish parent, a fact that flits in and out of Morante’s work like a family secret. In History (1974), her best-known and probably best novel, a widowed schoolteacher named Ida is raped by a German soldier and becomes pregnant with a second child. Her fear about the imminent rape is tempered only by her real terror: that the German will discover that her mother was a Jew. Her mother has already escaped her worries through insanity and drowned herself trying to swim to Palestine. Ida raises her children alone in Rome. She fears what will happen if someone learns about Useppe, her son born out of wedlock. She leaves him at home, with a dog as a babysitter. At school, she teaches her students about the glory of Mussolini. “Copy out three times in your good notebooks the following words of the Duce,” she tells them. Lonely and lost, she wanders through the ghetto in a confused search for family or connection. In one of the book’s most remarkable scenes, Ida watches Jews being deported by train without realizing what is going on:

The interior of the cars, scorched by the lingering summer sun, continued to reecho with that incessant sound. In its disorder, babies’ cries overlapped with quarrels, ritual chanting, meaningless mumbles, senile voices calling for mother…. And at times, over all this, sterile, bloodcurdling screams rose; or others, of a bestial physicality, exclaiming elementary words like “water!” “air!”

The book is overtly political: Morante punctuates the story of Ida and her two sons with summaries of what’s happened in any given year of the war, like intertitles in a silent movie: “December [1941]: Leningrad does not surrender.” But the war is seen at eye level, viewed only through characters who have lost nearly everything but can’t put their grief into words. Ida doesn’t quite understand the photographs of concentration camps that appear in the newspaper. She tears them up and tells Useppe to do the same. “Throw away that nasty paper! It’s ugly!” she says. “Perhaps a week afterward,” Morante writes, “Ida was wakened in the night by a curious prolonged sob. And when she had turned on the light, she saw Useppe sitting beside her, half out of the sheet, waving his little hands frantically…. ‘It’s uggy…It’s uggy!,’ he moaned.”

History is the most capacious of Morante’s books. The story seems to wish to be several things at once: dispassionate and warm, realistic and magical. When Ida and Useppe return to Rome after several months in a refugee camp called “the Thousand,” Morante begins to recount their fate from the point of view of their dog, Bella. It’s amazing that the project hangs together, a feat Morante accomplishes through an evenness of tone and an innate understanding of storytelling. The book’s Italian title, La Storia, means both “history” and “story,” and it is one of Morante’s most powerful insights that the former too often lacks the latter: the more people die, the less we see them as people, with loves and fears and hopes. When it was published, she insisted that it be made widely available as a cheap paperback. The book sold nearly a million copies within a year. An article from The New York Times described how “for the first time since anyone can remember, people in railroad compartments and espresso bars discuss a book—the Morante novel—rather than the soccer championship or latest scandal.”

Advertisement

“I should be grateful to Mussolini,” Morante once said.

In 1938, by introducing the racist laws, he made me realize that I myself was a Jew; my mother was Jewish, but the thought had never crossed my mind that there was something peculiar about having a mother whose father and mother used to pray in a synagogue…. When the Germans took over Rome in 1943, I learned a great lesson, I learned terror.

Still, what interests Morante in religion is not heritage but faith: how necessary it remains for human survival, even—and especially—when contradicted directly by every fact of life. Morante herself was a practicing Catholic. She insisted on being married in a church and refused to divorce Moravia when he demanded it so he could marry again. “The lack of religious meaning seems to me to be one of the major problems of our time,” she wrote. “Without religion, we cannot live.” (She admired Simone Weil, herself a Jew who turned to Catholicism.)

Morante’s characters are constantly clinging to illusion, even as the realities of the world crowd around, ready to shatter their beliefs. The only real attempt to understand what is happening in History comes from Davide Segre, a Jewish anarchist who meets Ida and Useppe in the refugee camp and slowly loses his mind on drugs. Davide is the only man in the book to have even a theoretical understanding of the larger reasons for the present disarray: “The word Fascism is of recent coinage, but it corresponds to a social system of prehistoric decrepitude…in reality, there has existed no other system but this.” But it does him no good. By the end of the novel he’s alone in his apartment, raving about the Antichrist and revolution, his face “walled-up in a directionless stare, a kind of white and void ecstasy, like that of a man accused but not confessing, when the torture machinery is shown to him.” Several pages later, he dies of an overdose.

Reading Morante today, what’s particularly striking is how closely she ties the hatred of women to other kinds of political violence. One of the best-drawn characters in History is Nino, Ida’s older son, who becomes a Fascist, then a Communist, then a war profiteer, in no small part because he’d rather hang out with blackshirts than listen to his mother. Some of the most telling scenes in the book show how rambunctious teenage energy quickly finds an outlet in the growing Fascist movement. Early in the novel, Nino decides to drop out of school. His mother objects. “Aw, Mà, why don’t you cut it out?” he pleads, and then, sensing her disapproval, begins to sing

Fascist anthems, like an immense chorus, improvising some obscene variants on them, to make things worse. At this point, as could have been foreseen, fear annihilated Ida. Ten thousand imaginary policemen spurted from her brain within that explosive room, while Nino, proud of his success, actually began singing “Red Flag.”

Arturo Gerace, the main character in Arturo’s Island, first published in 1957 and set in the late 1930s, has imbibed misogyny since birth. “Of the many evil females one can meet in life, the worst of all is one’s own mother! That is another eternal verity!” his father tells him. He lives on Procida, off the coast of Naples, but from the beginning it is clear that the island is not a sunny idyll for vacations by the beach. With its volcanic rock, ancient craters, and large prison, it is threatening and unwelcoming, especially to the women who live there:

The women, following ancient custom, live cloistered like nuns. Many of them still wear their hair coiled, shawls over their heads, long dresses, and, in winter, clogs over thick black cotton stockings; in summer some go barefoot. When they pass barefoot, rapid and noiseless, avoiding encounters, they might be feral cats or weasels.

They are rarely seen. “They never go to the beach; for women it’s a sin to swim in the sea, and a sin to watch others swimming.” In fact the entire island seems misogynistic, down to the volcanic core:

When a girl was born on Procida, the family was displeased…. They were small beings, who could never grow as tall as a man, and they spent their lives shut up in kitchens and other rooms: that explained their pallor. Bundled into aprons, skirts, and petticoats, in which they must always keep hidden, by law, their mysterious body, they appeared to me clumsy, almost shapeless figures.

Arturo doesn’t know any women. His mother died in childbirth. He only has a picture of her: “In her black eyes you can read not only submissiveness, which is usual in most of our girls and young village brides, but a stunned and slightly fearful questioning.” He doesn’t go to school. He roams and swims and sails while his father, Wilhelm, is off on unknown adventures. The only female being he spends time with is his dog, Immacolatella, who accompanies him on his daily explorations. The dog is not immune from the island’s curse. She becomes pregnant, and delivering the puppies kills her.

Arturo loves his father, whom he considers to be a great hero. The boy spends his days reading chivalric romances and stories of great soldiers of the past: “The books I liked most…were those which celebrated, with real or imagined examples, my ideal of human greatness, whose living incarnation I recognized in my father.” He imagines himself and his father within them. Most of all, he longs to be appreciated by his father: “When I have wrinkles, too, it will be a sign that I’m grown up, and then he and I can be together always.”

The prose here is distant, stiff, as if descended from the chivalric tales that Arturo reads, and is tempered only by Morante’s soft touch. Arturo is young and naive, but Morante preserves the childish seriousness with which he takes his own ideas, which he records in a “kind of Code of Absolute Truth”:

I. THE AUTHORITY OF THE FATHER IS SACRED!

II. TRUE MANLY GREATNESS CONSISTS IN THE COURAGE TO ACT, IN DISDAIN FOR DANGER, AND IN VALOR DISPLAYED IN COMBAT.

V. NO AFFECTION IN LIFE EQUALS A MOTHER’S.

Italian speakers have complained of the stilted way Morante’s prose comes out in English. “The effect is much like that of listening to opera on a scratchy record,” Tim Parks wrote in 1988. Ann Goldstein’s deft translation is an exception; it gives a clear sense of Morante’s love of the romantic, while preserving a lightness of tone that prevents the lyrical prose from calcifying.

When Arturo’s father brings back to the island a new wife only two years older than the now teenage Arturo, his world changes. “Tell him he can call me Ma,” she says. “This was really the boldest, most insulting provocation that the two of them could make!” Arturo thinks. The admiration Arturo felt for his father is now complicated by anger at this new wife, Nunziatella. Wilhelm doesn’t seem to like Nunziatella either. It’s not clear to Arturo why they married. Arturo’s father insults his wife, and Arturo, seeking his approval, does the same:

She looked at us, submissive but hesitant, and because of this hesitation my father’s desire became stronger. With unexpected, violent animation, he called her over again. Then I could see the enormous fear she had of him: it was as if she had to face an armed bandit, and she stood there, struggling between obedience and disobedience, unable to decide which of the two frightened her more. And in one step my father reached her and grabbed her: she trembled, with a wild expression, as if he had seized her in order to beat her….

“What do you imagine, Arturo? No, no: they deloused her thoroughly for her wedding.”

One of Morante’s insights here is how quickly men can bond over the hatred of women. Nunziatella’s presence alone seems to bring father and son together:

One would have said, at that moment, that, for the sole fact of existing and encumbering the air in front of him, she was committing a crime, she was threatening the right of Wilhelm Gerace.

Arturo tries to kiss Nunziatella, but she rejects him. He hits her instead. Arturo learns that his father is homosexual—he’s been pining after a prisoner from the mainland, who rejects him. Another illusion shattered. Wilhelm has been traveling not to exotic places but to nearby Naples in search of lovers. (There’s something a little dated in Morante’s equation of homosexuality with tortured mother-love, whether she realized this or not. “El niñomaderero,” thinks Manuel in Aracoeli. “The mama’s-boy fairy tale is stagnant, typical retrieval of a psychoanalytic session, or subject of an edifying pop song.”)

Having lost his faith in everything, Arturo goes off to World War II: “What I wanted was to fight in order to learn to fight, like an Oriental samurai. The day I was a master sure of my valor, I would choose my cause.” It’s the first time that the outside world has punctured his consciousness. In war, he decides, he can become a great hero. But the reader—whether in 1957 or now—knows that even if he makes it out alive, as an Italian, he will lose, which for a hero is a fate worse than death.

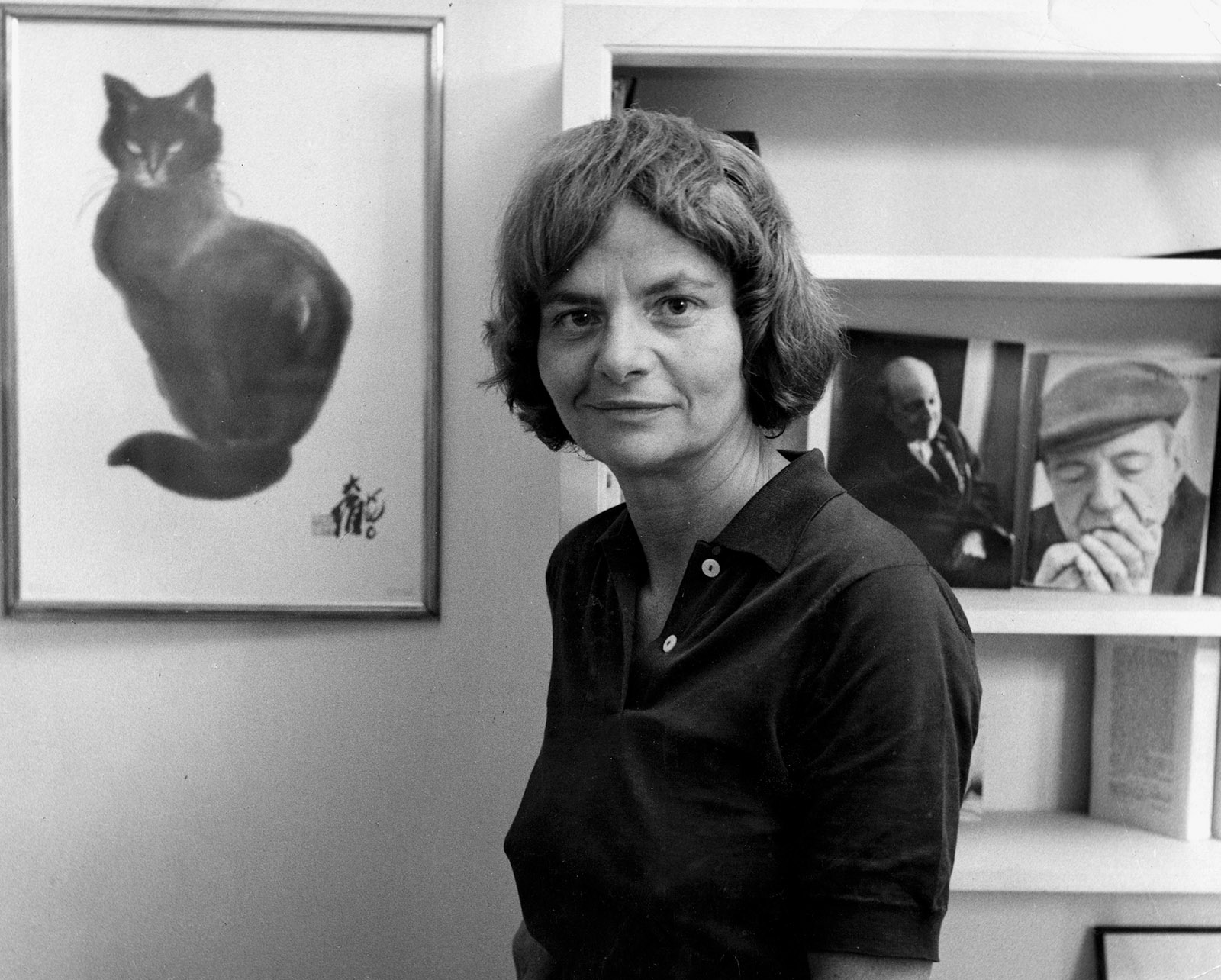

Morante was not interested in the women’s movement. She refused to contribute to anthologies collecting work under that rubric, and said that she identified more with the boys in her books than the women. “Arturo c’est moi,” she declared to a friend, though one suspects that it was really Flaubert she was thinking of. Still, her books were popular among Italian feminists. When the Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective, a group of Italian feminists in the 1970s, put together a list of “mothers” for women to read, Morante was at the top. Now, again, our catalogs are filled with mothers. I’m eager to see what the daughters and granddaughters reading them now will produce in response.