In a courtroom in Zharkent, Kazakhstan, in July 2018, a former kindergarten principal named Sayragul Sauytbay calmly described what Chinese officials continue to deny: a vast new gulag of “de-extremification training centers” has been created for Turkic Muslim inhabitants of Xinjiang, the Alaska-sized region in western China. Sauytbay, an ethnic Kazakh, had fled Xinjiang and was seeking asylum in Kazakhstan, where her husband and son are citizens. She told the court how she had been transferred the previous November from her school to a new job teaching Kazakh detainees in a supposed “training center.” “They call it a ‘political camp’…but in reality it’s a prison in the mountains,” she said. There were 2,500 inmates in the facility where she had worked for four months, and she knew of others. There may now be as many as 1,200 such camps in Xinjiang, imprisoning up to a million people, including Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and especially Uighurs, who make up around 46 percent of Xinjiang’s population.

Sauytbay’s testimony provided the first dramatic public evidence from a Chinese citizen of the expanding gulag in Xinjiang. But news of it has been emerging since 2017, thanks to remarkable reporting by Gerry Shih (now at The Washington Post) for the Associated Press and Josh Chin, Clément Bürge, and Giulia Marchi for The Wall Street Journal, as well as important early stories from other researchers and correspondents, including Maya Wang (Human Rights Watch), Rob Schmitz (NPR), and Megha Rajagopalan (BuzzFeed News). Especially important is the Washington, D.C.–based Radio Free Asia Uighur service, which has for years provided detailed, accurate coverage despite notorious controls on information in Xinjiang.

At first, officials in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) denied there were any camps. Then state media briefly floated a story that 460,000 Uighurs from southern Xinjiang had been “relocated” to “jobs” elsewhere in the Xinjiang region. There have been no further announcements about that jobs program, and the explanation seems to have been dropped. When confronted at an August 2018 UN hearing by Gay McDougal, a member of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the Chinese delegation denied that there were any “reeducation” camps, while admitting that there were “vocational education and employment training centers” and other “measures” to counter “extremism.” When pressed again at the UN Human Rights Council’s universal periodic review in November 2018, the PRC representative accused “a few countries” of “politically driven accusations” and repeated that the camps were simply providing vocational training to combat extremism.

People outside Xinjiang first began to learn about the camps in 2017. Uighurs abroad grew alarmed as friends and relatives at home dropped out of touch, first deleting phone and social media contacts and then disappearing entirely. Uighur students who returned or were forced back to China after studying in foreign countries likewise vanished upon arriving. When they can get any information at all, Uighurs outside China have learned that police took their relatives and friends to the reeducation camps: “gone to study” is the careful euphemism used on the closely surveilled Chinese messaging app WeChat.

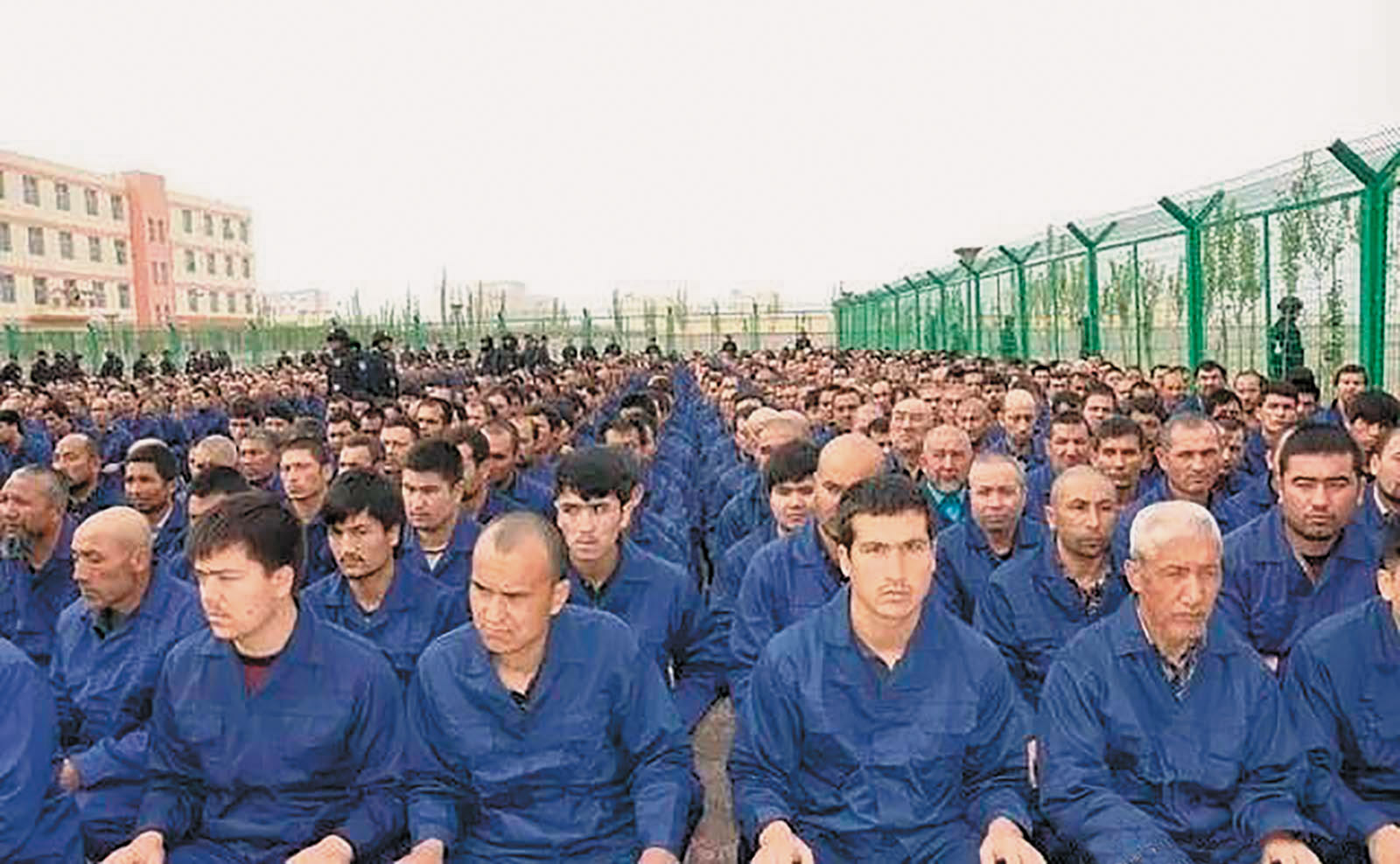

The punitive nature of the new detention facilities springing up in the desert, ringed by high walls and barbed wire and flanked by guard towers and police boxes, became apparent from photos and reporting by the fall of 2017. Our best sense of what is happening inside the camps comes from former prisoners, one writing anonymously in Foreign Policy, and others interviewed in Kazakhstan by Shih and Emily Rauhala for The Washington Post: detainees must sing anthems of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), disavow Islam, criticize themselves and their family’s beliefs, watch propaganda films, and study Chinese language and history. They are told that their culture is “backward.” Some must memorize the moralizing Three-character classic (San zi jing), a classical Chinese children’s primer in trisyllabic verse, abandoned as a pedagogical text elsewhere in China for over a century. Cells are crowded and food is poor. Those who complain reportedly risk solitary confinement, food deprivation, being forced to stand against a wall for extended periods, being shackled to a wall or bolted by wrists and ankles into a rigid “tiger chair,” and possibly waterboarding and electric shocks.

Shohrat Zakir, chairman of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, said in an October 2018 interview with Xinhua that internees must learn Chinese,

gain modern science knowledge and enhance their understanding of Chinese history, culture and national conditions…learn legal knowledge, including the content of the Constitution, Criminal Law and Xinjiang’s Counter-extremism regulations, as well as acquire at least one vocational skill…to suit local conditions and the job market.

Given this imposing curriculum, it is not surprising that we know of almost no one who has been released after being interned in the Xinjiang prison camps, and that we don’t know what internees will face if and when they are let go. There is growing evidence from relatives’ accounts, satellite photos, and internal documents that following a course of indoctrination, internees are forced to work in factories in or near the camps.

Advertisement

Research by Adrian Zenz of the European School of Culture and Theology confirmed the frightening extent of the camps and provided an estimate of how many people are confined in them. Zenz has tracked the discussion of Xinjiang “de-extremification” and “transformation through education” in Chinese media and party journals for several years. He identified seventy-eight bids by contractors to build, expand, or upgrade internment camps; several of them were planned to exceed 100,000 square feet in area, and one was nearly 900,000 square feet. Documentary evidence for the rush of camp construction is corroborated by satellite photographs of the sites—many first compiled from Google Earth as a remarkable personal project by Shawn Zhang, a law student at the University of British Columbia, and since confirmed and expanded by professional remote-imaging firms working with the BBC and other media. Another indication of the breadth of the internment comes from visitors to Xinjiang, who have commented on the shuttering of Uighur shops and a noticeable lack of people, especially Uighurs between fifteen and forty-five, on the streets.

Comparing data from leaked documents and statements by local officials with population data, Zenz and other researchers estimated that between several hundred thousand and over a million people are interned in the reeducation camps. In February 2018 a Uighur activist media outlet in Turkey released a document it says was leaked by a “believable member of the security services on the ground” in Xinjiang. The document, dating from late 2017 or early 2018, tabulates precise numbers of internees in county-level detention centers, amounting to 892,329 (it excluded municipal-level administrative units, notably the large cities of Urumqi, Khotan, and Yining). Though the document’s provenance cannot be confirmed, if genuine it supports the estimates of a million or more total internees. (The US State Department estimates that between 800,000 and two million Xinjiang Muslims are interned in the camps.) These estimates do not include the rapidly increasing numbers of people in ordinary prisons: according to PRC government data, criminal arrests in Xinjiang increased by 200,000 between 2016 and 2017, and amounted to 21 percent of total arrests in China in 2017, even though Xinjiang has only 1.5 percent of China’s population. It is believed that the PRC has so far locked up over 10 percent of the adult Muslim population of Xinjiang.

How did the PRC come to this? I see two broad reasons: an official CCP misunderstanding of what Islam means to most Uighurs and other Muslim groups, and a recent CCP embrace of Han-centric ethnic assimilationism, an idea that runs counter to traditional Chinese modes of pluralism. (The Han are the majority ethnic group in the PRC as a whole, though not in the former colonial territories of Xinjiang and Tibet.)

The people of the Tarim Basin, the ancestors of modern Uighurs, along with Turkic tribes of the steppes and mountains (including the Kazakhs’ and Kyrgyz’ forebears), converted to Islam in several waves beginning around the year 1000. Central Asian Islam is quite different from that of the Middle East, however, and especially from that promoted in modern times by Wahhabi and Salafi groups sponsored by the House of Saud. Uighur prayer can involve chanting and dancing, and music is not forbidden. Visiting the shrines of venerated saints and telling their stories not only structure Uighur religious practice but geographically shape their identity, as the historian and Uighur scholar Rian Thum has shown in his ingenious book, The Sacred Routes of Uighur History (2014). Sufi saints were so important in Uighur Islam, Thum writes, that a circuit pilgrimage of their tomb shrines, all found within Xinjiang’s borders, was an acceptable substitute for making the hajj to Mecca.

Since 1949, Chinese policies have tended to undermine indigenous Uighur Islam and to enforce, through the party-controlled Islamic Association of China, an idealized version of Islam modeled in part on Sunni practice as promoted by Saudi Arabia. Besides reflecting Beijing’s diplomatic ties with Riyadh, these policies may echo a traditional Chinese notion, derived from experience with Buddhistic millenarianism, that religions have safe “orthodox” and dangerous “heterodox” expressions.

Although the CCP has since reversed course and rails against the dangers of “Arabization,” it has not revised its intolerance of Sufi practices in Uighur Islam. By repressing Uighur culture and discriminating against Uighurs, and inadvertently promoting a version of Islam more in line with Saudi practice, the PRC government has increased the attractiveness to Uighurs of Salafi ideas from outside while undermining indigenous defenses against such an ideology. Rahile Dawut, an internationally renowned ethnographer and scholar of Uighur culture and religion at Xinjiang University, could have explained this to Chinese authorities—but she was disappeared in late 2017, another victim of the current mass internment.*

Advertisement

Xinjiang is part of the PRC today only because the Manchu-ruled Qing empire (1636–1912) conquered it in the eighteenth century, in the course of a westward expansion that also included the annexation of Mongolia and Tibet. The Qing administered the Uighurs through local elites, under light-handed military supervision, while promoting trade and agricultural development. The Manchus prohibited Chinese settlement in densely Uighur areas for fear of destabilizing them, and did not interfere with Uighur religion, food, or dress. This culturally pluralist imperialism worked well, and despite a series of minor incursions from Central Asia into southwest Xinjiang, from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century the region was on the whole peaceful—enough so that the Uighur population increased fivefold and the economy expanded. Troubles in the region only began when rebellions in the rest of China cut off Qing funding for its Xinjiang officials and soldiers. Corruption, rebellions, and invasions ensued.

As Beijing sought to regain and maintain control over Xinjiang, a debate emerged pitting Qing-style imperial ethno-pluralism against Han-centric nationalistic assimilationism. The nineteenth-century political thinker Gong Zizhen and General Zuo Zongtang (of the eponymous chicken dish) advocated colonial settlement of Xinjiang by Han Chinese and government by Han (rather than Manchu or indigenous) officials. Zuo’s successors tried this in a limited fashion until the Qing fell in 1912. Thereafter, during the nearly four tumultuous decades until the Communists took power in 1949, most rulers in divided Xinjiang, whether Han warlords, rebel Muslims, or Soviet puppets, built regimes around various types of ethno-pluralism, letting Uighurs govern Uighurs, Kazakhs govern Kazakhs, Mongols govern Mongols, Han govern Han, and so on, in a patchwork across the diverse region.

When the CCP took over, it applied this ethno-pluralist approach, already entrenched in Xinjiang, nationwide. As an ethnically Han Communist Party reoccupying the former Qing empire in Central Asia, the CCP faced the same problem as the Russocentric Soviets with their tsarist legacy: how to run an empire without looking like colonialists. Loosely following the Soviet example, the PRC granted fifty-five non-Han peoples official status as minzu (nationality or ethnic group), with special rights enshrined in the Chinese constitution. Some nominally autonomous administrative territories were named after minzu: hence the province-sized territories of Xinjiang and Tibet became the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region and the Tibetan Autonomous Region of the PRC.

The PRC minzu system also echoed aspects of Qing imperial pluralism: beneath the supreme central CCP power, the fifty-six minzu (including Han) were supposed to stand as equals. Han civilization was, in theory, not considered superior. Actual practice varied, but in the 1950s and again in the 1980s the party did make a show of defending minority groups against “great Hanism,” China’s equivalent of the “great Russian chauvinism” denounced in the USSR. Except during the Cultural Revolution, the minzu system generally celebrated China’s cultural diversity, encouraging publishing in non-Han languages, putting minorities on the currency, and featuring them at public events in colorful “traditional” dress. Western observers have found the kitschy parade of singing and dancing minorities offensively exoticizing, but insofar as it bolsters their cultures, China’s non-Han minzu generally support top-down PRC multiculturalism. The strongest critique delivered by Ilham Tohti, a Uighur economist sentenced to life imprisonment for “separatism” in 2014, was simply to press for genuine observance of the minzu-friendly laws and constitutional provisions already on the books.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, however, which many Chinese political theorists blamed on Soviet nationality policies, a reassessment of the ethno-pluralist minzu system began. The former Qing imperial territories in Xinjiang and Tibet remained restive, despite rapid economic growth. After riots in Tibet in 2008 and Xinjiang in 2009, some scholars of ethnic studies in Beijing who were close to CCP leaders suggested that China’s minzu system was part of the problem and began discussing how to revise it.

The strongest proponents of a radically revised “second generation minzu policy,” Hu Angang (director of the Center for China Studies at Tsinghua University) and Hu Lianhe (then a counterterrorism researcher, now a leading official at the United Front Work Department of the CCP), argued that only after assimilating minorities into a broader pan-Chinese ethnicity (Zhonghua minzu) would China be stable. The two Hus proposed, in effect, to abandon China’s traditional imperial pluralism, as continued under the PRC minzu system, in favor of a concept of unitary identity reminiscent of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century European nationalism.

Terms such as “fusion,” “blending,” and “melting” entered the discussion, and in 2015 scholars and ideologues debated whether Sinicization (Hanhua), the notion that over the ages Chinese civilization spontaneously and peacefully assimilated neighboring peoples, had ever occurred. The myth of Sinicization has been long debunked by Western and many Chinese historians, who accept that acculturation between contiguous groups can happen, but is neither inevitable nor one-way. Yet the idea of Sinicization as a magical power of Chinese civilization is attractive to CCP nationalists, along with the concomitant fable that China only ever expanded peacefully.

The next stage in the PRC transition from imperial pluralism to Han assimilationism has been the demonization of religion. Although today official sources still publicly blame ethnic unrest in Xinjiang and Tibet on extremist ideas from abroad and small numbers of individuals, articles in party journals and leaked internal discussions reveal that the CCP leadership increasingly views religious belief itself as contradictory to the unitary pan-Chinese identity it desires, and it hopes to cure whole populations of supposedly deviant thinking. A speech distributed as an audio recording online in October 2017 by the Xinjiang Communist Youth League, apparently intended to reassure Uighurs, fully embraced the medical metaphor:

If we do not eradicate religious extremism at its roots, the violent terrorist incidents will grow and spread all over like an incurable malignant tumor.

Although a certain number of people who have been indoctrinated with extremist ideology have not committed any crimes, they are already infected by the disease. There is always a risk that the illness will manifest itself at any moment, which would cause serious harm to the public. That is why they must be admitted to a re-education hospital in time to treat and cleanse the virus from their brain and restore their normal mind. We must be clear that going into a re-education hospital for treatment is not a way of forcibly arresting people and locking them up for punishment, it is an act that is part of a comprehensive rescue mission to save them.

The PRC does have some legitimate concerns about Uighur unrest. Sporadic incidents of resistance broke out in the late 1980s and 1990s, including student marches, a small uprising (in Baren, outside Kashgar), bombings of a bus and a hotel, and a major demonstration that turned violent in Yining (Ghulja) in 1997. Before 2001, the PRC generally attributed such “counter-revolutionary” events to “Pan-Turkism/Pan-Islamism,” designations that, although anachronistic by the late twentieth century, did recognize the ethno-national as well as religious roots of Uighur identity. After the September 11 attacks, however, taking advantage of the terminology used in the Bush administration’s “global war on terror,” the PRC rebranded all Uighur dissent as Islamic terrorism. The PRC State Council issued a white paper in early 2002 that cited, with few details, 162 deaths and 440 injuries from acts of “terrorism” in the 1990s, and also listed a number of Uighur separatist groups. Only in a few cases did the white paper attribute specific acts to named groups.

In return for China’s vote in November 2002 for UN Security Council Resolution 1441 condemning Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, the Bush administration agreed to list one Uighur group as an international terrorist organization. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) was chosen, although it was extremely small, because of evidence that it had had some contact with Osama bin Laden from its base in Afghanistan. (“East Turkestan” was a term embraced by Turkic groups who established two short-lived independent states in parts of Xinjiang in 1933 and 1944–1949. Many Uighurs in diaspora prefer it to the colonial name “Xinjiang,” which literally means “New Frontier.”)

The Chinese white paper had not claimed that ETIM perpetrated any violent acts, but the US government’s public statement mistakenly attributed all ten years’ worth of incidents mentioned in the white paper to ETIM. Thus was born the notion, still prevalent inside and outside China, that an organized terrorist group is responsible for separatist violence in Xinjiang. (ETIM collapsed in 2003 after Pakistani troops killed its leader, Hasan Mahsum, in Waziristan, though someone, under the new sobriquet of the Turkestan Islamic Party, subsequently claimed in videos to have taken up ETIM’s mantle.)

Despite constant warnings in Chinese propaganda and foreign media, for years the much-prophesied Islamic terrorism failed to occur. From 1990 through the Beijing Olympics of 2008, while Xinjiang was not entirely quiet, the incidents that did occur did not fit the jihadist pattern of attacks on random civilians. Though official Chinese statements and state media call all Uighur resistance “terrorism” and “separatism,” most events of the past decade, as best we can tell through the heavy media controls on Xinjiang, are what Western observers would label “unrest” or “resistance” rather than “terrorism”: for example, street demonstrations or attacks on local government offices or police targets by farmers armed with knives or agricultural tools. One demonstration in Urumqi on July 5, 2009, after being repressed by armed police, erupted into the bloodiest civil unrest in Xinjiang since the Cultural Revolution. Nearly two hundred Han died, thousands of Uighurs were arrested, and many died when Han vigilantes took to the streets on subsequent days. The number of Uighur casualties in the riots and during the backlash has never been released. In the aftermath, authorities cut off phone and Internet service to Xinjiang for ten months. (Such Internet “kill-switch” capability has now reportedly been installed across China.)

Though horrific, the Urumqi “7-5 Incident” was a race riot, not a premeditated terrorist attack or an expression of religious extremism. However, some events since 2008 do resemble jihadi terrorism in their random targeting of civilians and possible religious motivation. In March of that year a Uighur woman allegedly tried to ignite flammable liquids on a plane after takeoff. In October 2013 a Uighur man drove an SUV with his wife and mother inside into a crowd in Tiananmen Square, killing two tourists; the occupants of the SUV perished when it then burst into flames. In March 2014 eight Uighurs armed with knives killed thirty-one people at the railway station in Kunming, in southwest China. The following month, while President Xi Jinping was visiting Xinjiang, three people used knives and (possibly malfunctioning) explosives to stage an attack at the Urumqi railway station, killing three. In May 2014 five assailants in two SUVs killed forty-three people on an Urumqi market street with explosives. And in September 2015, in a strange incident that may have been more labor dispute than terror attack, seventeen Uighurs, including women and children, reportedly killed fifty people at a mine in remote Baicheng country, in Xinjiang. They then fled to a cave in the mountains, where Chinese troops, after an extended manhunt, flushed them out with flame-throwers and shot them.

It is not the case, then, that China faces no threat of Uighur violence, but it exaggerates the threat, often mischaracterizes it as terrorism, and has adopted wildly excessive and indiscriminate measures in response. After years of “strike hard” crackdowns, the situation for Xinjiang’s Turkic Muslim groups worsened sharply after August 2016, when the new Xinjiang party secretary, Chen Quanguo, was appointed. Chen came from a poor family in Henan province, where he climbed the CCP ranks and served there under governor Li Keqiang (now China’s premier). In 2011 Chen was sent to Tibet, which had been roiled by riots and a series of self-immolations by Buddhist monks. Chen quelled resistance in Tibet through grid policing, a dense network of “convenience police stations” in urban parts of Tibet, and thousands of new police. Chen brought these techniques to Xinjiang, and from 2017 complemented grid policing with the rapidly expanding reeducation gulag. He has since been appointed to the Chinese Politburo.

Since Chen’s arrival, Xinjiang, too, has recruited tens of thousands of security personnel, making the region likely more highly policed, per capita, than East Germany was before its collapse in 1989. Chen’s security grid features police boxes every few hundred yards, constant patrols, armored personnel carriers, and ubiquitous checkpoints. Recent reporting has also revealed a vast and expanding surveillance network of facial-recognition cameras, cell-phone sniffers, GPS vehicle tracking, and DNA, fingerprint, ocular, voice-print, and even walking-gait scans that are linked to the growing database of personal information gathered from mandatory surveys of the travel history and religious practices of Xinjiang residents and their families. These surveys are scored: devout Muslims lose points for regular prayer, which the state deems a potential risk factor for extremism. Simply being an ethnic Uighur results in a 10 percent deduction.

Distinctive Uighur religious and other cultural practices are increasingly circumscribed or legally banned. School instruction in the Uighur language, once available from kindergarten to the university level, has been eliminated. Xinjiang authorities now define as “extremist” veils, head coverings, “abnormal beards,” long clothing, fasting at Ramadan, the greeting assalam alaykum (“peace be upon you” in Arabic), avoiding alcohol, not smoking, “Islamic” baby names like Muhammad and Fatima, the star and crescent symbol, religious education, mosque attendance, simple weddings, religious weddings, weddings without music, cleansing a corpse before burial, burial itself (as opposed to cremation), visiting Sufi shrines, Sufi religious dancing, praying with feet apart, foreign travel or study abroad, interest in foreign travel or study abroad, communicating with friends or relatives outside China, having the wrong kinds of books on one’s shelves or content on one’s phone, and avoidance of state radio or television. Though generally not publicly religious, members of the Uighur cultural, academic, and business elite, including top administrators of universities and chief editors of presses, have been singled out for detention.

PRC officials promote these policies as a cure for “extremism.” The official definition of “extremism,” however, has progressively expanded, and authorities confine people in the reeducation camps for mundane Islamic practice and, indeed, for much of what it means to be a Uighur. “It is impossible to be Uighur without violating these new rules,” as Rian Thum puts it. In statements obtained by Radio Free Asia, local officials have admitted that they have been given quotas of Muslims to send into reeducation. Qiu Yuanyuan, a scholar at the Xinjiang Party School, in a 2016 paper since removed from the Internet, warned explicitly against quotas for reeducation, on the grounds that such an imprecise numerical approach could backfire. This suggests that the Party was discussing them internally at that time. Based on figures from localities around the region, Adrian Zenz estimates that up to 10 to 11 percent of the Uighur and Kazakh populations are currently detained, though quotas of up to 40 percent have been cited for some areas, and camp capacity continues to grow.

There is a curious cultural specificity to some of the measures in Xinjiang: this is a security state with Chinese characteristics. The traditional Chinese practice of assigning groups of ten households to mutual-accountability units has been revived in parts of Xinjiang, where Uighur families are now made collectively responsible. Because some of the terrorist attacks involved knives (and Chinese believe all Uighur men must carry a blade), authorities in Xinjiang implemented strict knife control: before sale, even kitchen knives must be etched with a QR code carrying the buyer’s personal ID card number and other data. Uighur cooks in restaurant kitchens chop with cleavers chained to the wall.

In an echo of the Cultural Revolution practice of “sending down” city dwellers to the countryside, Chinese officials and intellectuals, mainly Han, have since 2014 been dispatched to live for certain periods in the homes of Uighur families. During a campaign named “Ethnicity Unity ‘Becoming Family Week’” in December 2017, a million CCP cadres moved in to live, eat, and work with Uighurs. In these repeated stays, the Han officials are meant to teach Chinese to Uighur “little brothers” and “little sisters,” instruct them in Xi Jinping Thought, and sing the Chinese national anthem, while helping out around the house.

In a music video celebrating the campaign, produced by the Xinjiang Communist Youth League, the Han arrive in the village wearing hiking boots and carrying backpacks, as if on a camping expedition. Images roll past of the Han and Uighurs looking at books, sweeping the dirt courtyards, and eating together. On the soundtrack, a singer raps in Chinese that living among the Uighurs helps one recapture the romantic revolutionary spirit of Party General Secretary Xi Jinping’s years as an “educated youth” in a rural Shaanxi village.

But a triumphant social media post from the Bingtuan Broadcast Television University (BBTU), which sent teams to the Uighur village of Akeqie Kanle, revealed that the home visits are more about surveillance than ethnic amity: “The [BBTU] work team is resolute. We can completely take the lid off Akeqie Kanle, look behind the curtain, and eradicate its tumors.” A few months after the Bingtuan work teams’ visits, a fifth of Akeqie Kanle’s adult population had disappeared into the camps.

The CCP’s mass internment and coercive indoctrination of Muslim minorities is intended to forcibly remake their identity. The word “conversion” (zhuanhua) appears in official Chinese names for the camps (jiaoyu zhuanhua peixun zhongxin, “Educational Conversion Training Center”) and in the “de-extremification” regulations. The party now increasingly finds Islamic faith and even non-Han ethnic culture to be inimical to the goal of homogeneous Chinese identity.

There are grave dangers to locking up a million people for coercive indoctrination at the hands of hastily mustered, ill-trained guards. Even if the Xinjiang reeducation gulag avoids the widespread torture, rape, and killing that have accompanied ethnic cleansing elsewhere, and Uighurs and other Turkic peoples can endure the psychological trauma of the camps, it is a tragedy for the PRC to abandon Chinese traditions for managing diversity in favor of the Western ideology of nationalism, so ill-fitted to the globalizing age the CCP wants to help shape. The CCP, after all, invented Autonomous Regions, Special Economic Zones, and the notion of “One Country, Two Systems.”

The PRC once experimented creatively with models of reallocated political and economic sovereignty in order to address frontier issues left over from the Qing imperial past (Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, Taiwan). And it did so with policy ideas drawn from that same past (imperial pluralism, frontier trade enclaves, tax-free zones, treaty ports). What is sometimes called the “Xinjiang Problem” is but one dimension of a broader question: Can today’s PRC tolerate diversity? Or does it plan to resolve its Tibet Problem, its Hong Kong Problem, and its Taiwan Problem as it does its Xinjiang Problem: with concentration camps?

—January 10, 2019

This Issue

February 7, 2019

Imperial Exceptionalism

The Twisting Nature of Love

-

*

Dawut publishes mainly in Uighur and Chinese, but writes in English about mazars, or Sufi shrines, in Mazar: Studies in Islamic Sacred Sites in Central Eurasia, edited by Dawut and Sugawara Jun (Tokyo University Foreign Studies Press, 2016). A 2013 exhibition at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City of photographs by Lisa Ross highlighted the startling variety and abstract beauty of Uighur shrines (see illustration on page 40); that work is collected in her book Living Shrines of Uyghur China (Monacelli, 2013), which includes an essay by Dawut. ↩