Workmen throughout Syria are erecting bronze, stone, and concrete statues in what the government calls “liberated areas.” Some of the monuments are newly cast, while others have been in storage since the conflict began in 2011. At that time, protesters in rebellious cities like Dera’a and Homs were desecrating the sculptures of longtime president Hafez al-Assad, his successor Bashar, and Bashar’s older brother, Bassel, the designated heir who died before ascending the throne. It was perhaps an omen of the rebellion’s destiny that popular legend had a massive bust of Hafez in Idlib killing two demonstrators as it crashed to earth. Seven years on, the effigies, like the regime they embody, are back. The war isn’t over, but the postwar era has begun.

Outright victory remains elusive. The Syrian army controls about 60 percent of the land and 80 percent of the resident population of about 16.5 million people, leaving three sectors of the country yet to be “liberated”:

• Northern Aleppo province and the adjoining provinces of Afrin and Idlib near the Turkish border in the north, where the Turkish army and an estimated 70,000 insurgents rule about three million Syrians.

• The northeast beyond the Euphrates River, controlled by a largely Kurdish militia that depends for its survival on the estimated two thousand American Special Forces troops that Donald Trump recently promised to withdraw before changing his mind and committing them to longer duty in Syria.

• A twenty-one-square-mile “red zone” the US declared around its military base in the southern desert at Tanf village, near the intersection of Syria’s borders with Jordan and Iraq, which may revert to government control if Trump closes the base.

The Assad regime faces two tasks, neither easy: stabilizing, governing, and reconstructing the regions under its dominion; and clawing back the rest of the country. While waiting for the Turks, Americans, and jihadis to leave, the state is concentrating on the first objective.

“The big victory is not in war,” a professor at Damascus University told me, “but in peace.” The government must rebuild more than statues with money it does not have if it is to secure peace and a semblance of the status quo ante 2011. Foreign powers who backed Assad’s opponents for nearly eight years could be convinced to provide some funding, but only if he accepts reforms that would make him vulnerable to being replaced. “Assad didn’t step aside for peace when he was losing, and he is not going to step aside for money now,” observed an ambassador with long experience in Damascus. United Nations special envoy Staffan de Mistura, before the Norwegian diplomat Geir Pedersen succeeded him, conveyed Western conditions for aid that include a new constitution, internationally supervised elections, and an end to corruption. The opposition voiced the same demands. The West echoed the opposition’s demands at the start of the uprising, while refraining from requiring similar reforms in client states like Saudi Arabia.

When the UN asked Assad whether a proposed Constitutional Committee should have thirty or 150 delegates, he opted for 150. One diplomat asked me with a smile, “Can you imagine 150 Syrians agreeing on anything?” Arguments over the committee’s composition make Britain’s Brexit negotiations with the European Union look like tic-tac-toe. The delegates, whenever they assemble, must write a document that would allow the US, the EU, and the financial institutions they control to release funds for rebuilding. In any case, as a Syrian defector from the regime said, “You can make the best constitution in the world, but no one will apply it.”

The Arab states that paid jihadis and dispatched them into Syria show no concern about the niceties of constitutional government. Jordan, site of command and control for much of the insurgency, has reopened its border with Syria. The United Arab Emirates, which followed the lead of Saudi Arabia in assisting jihadi fighters attempting to overthrow Assad, has just reopened its embassy in Damascus. It won’t be long before the Arab League, which suspended Syria in November 2011, readmits the country to its ranks.

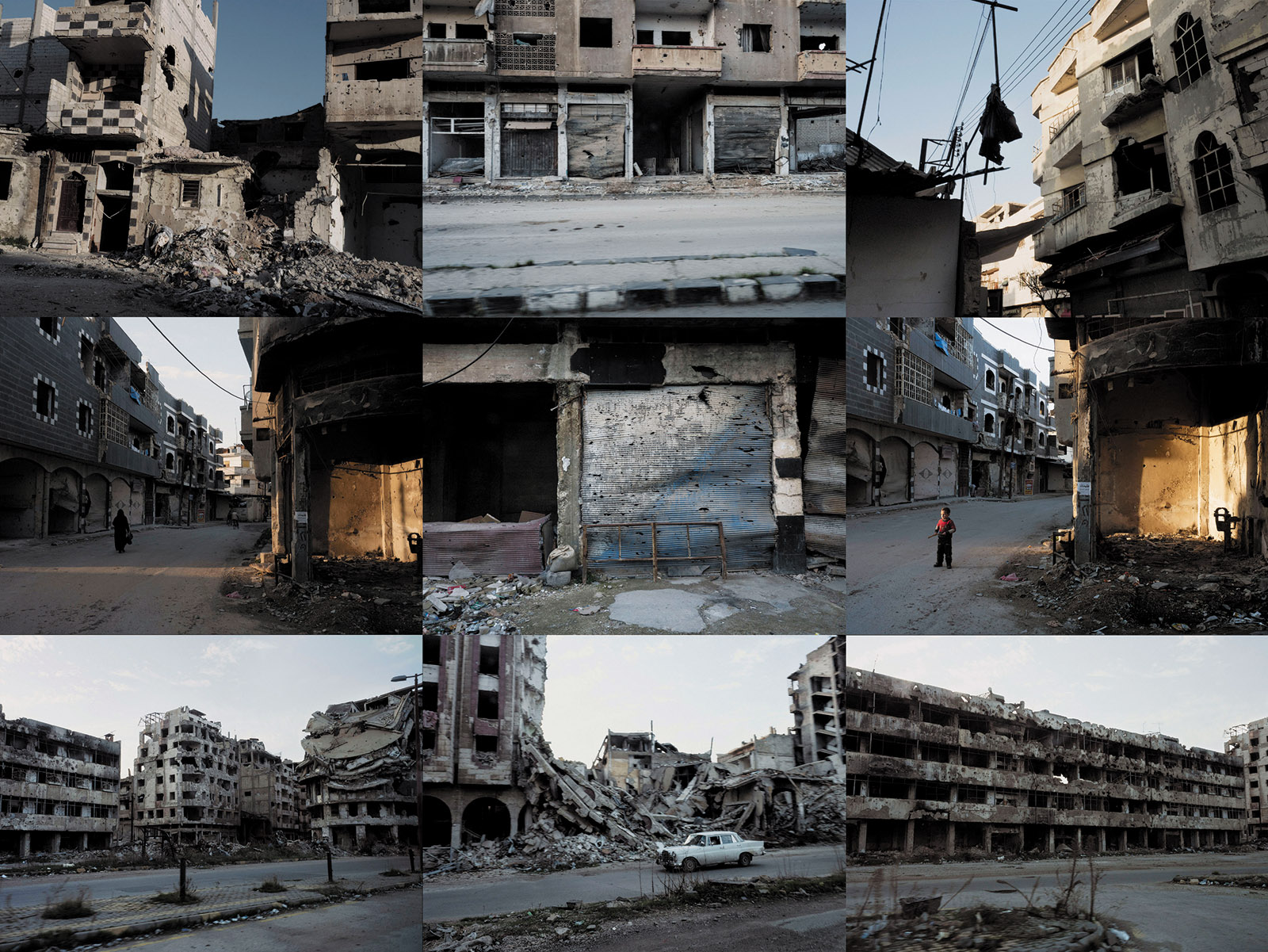

As winter envelops Syria in bone-chilling frost, some six million people, officially designated “internally displaced persons,” are without permanent shelter. For them as for about five million in exile, homecoming awaits the rebuilding of houses and roads as well as water, sanitation, and electrical infrastructure demolished in the fighting. In former battlefields, unexploded ordnance—land mines, booby traps, mortar shells, and cluster bombs—takes lives, limbs, and eyes, mainly of children, and must be removed. So too millions of tons of mangled concrete to make way for new water conduits, sewage channels, electricity pylons, schools, and clinics. Rebuilding a country requires more money than destroying it. Countries that dispatched billions in weaponry have become parsimonious about rebuilding—this applies as much to Russia and Iran on the government’s side as to the US, Britain, France, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar on the opposition’s.

Advertisement

“Everyone wants to come here, but they don’t know how,” said a European official who attended meetings with potential donors. Since US sanctions forbid donations and loans for reconstruction, some countries, including Germany, propose to channel aid to Syria by calling it “rehabilitation and not reconstruction.” At the same time, in a sign of schizophrenia not exclusive to Germany, State Secretary of the Federal Foreign Office Walter Lindner admitted that his ministry had paid €37.5 million to Syrian rebels in Idlib. Italy, while officially backing the American position on Syria sanctions, has opened channels to the Syrian government. Syrian security chief Ali Mamlouk, a target of US and EU sanctions, visited Rome in January 2018. Mamlouk has also been paying calls on his counterparts in Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The Czech Republic, whose embassy remained open throughout the war and represents US interests, plans to establish a school in Damascus. Several European diplomats in Beirut told me that their countries want a face-saving formula to reopen the embassies they closed in Syria when the US ambassador departed in 2012. “Europe has lost the battle” to unseat Assad, said one EU representative, “and still we don’t know what to do.”

Resident and expatriate Syrian business people are filling the vacuum left by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and overseas commercial banks prevented by US sanctions from assisting the Syrian economy. Shopkeepers have cleared rubble from their premises in Aleppo’s majestic old city, and new hotels are going up in Damascus to welcome the entrepreneurs the government imagines will descend on the capital to cash in on a promised building boom. Syria may eventually benefit from the disappearance of its archaic industrial plants, as Germany’s coal and steel industries did after World War II, by starting anew with modern machinery.

The Syriac Orthodox Church and private investors have committed $8 million to construct a state-of-the-art pharmaceutical factory in the ancient Christian village of Sednaya. The concrete structure atop a hill forty minutes north of Damascus is scheduled to begin production in the spring. On another of Sednaya’s hills, the Antioch Syrian University has just opened its doors to its first class, composed of 110 engineering and business students. Although backed by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate, it admits Muslims and offers no courses in religion.

One of the largest obstacles to development, apart from Western distaste for Assad, is corruption. Already endemic before the war, it has ballooned thanks to arms smuggling and sanctions dodging. The government has sporadically sponsored anti-corruption “drives” that few take seriously, given the popular belief that corruption starts at the top. When the minister of the interior, Major General Mohammed al-Sha’ar, arrested a civil service clerk named Riyyad al-Batal in Aleppo in early November for pocketing 50 Syrian pounds, about 10 cents, the whole country laughed. The man’s son wrote on Facebook that “no one dares to take bribes without directions by chairmen.” The son, it turned out, had been serving in the army since the start of the war. Three weeks later, Assad reshuffled his cabinet and appointed a new interior minister, demoting Sha’ar to a largely ceremonial post in the National Progressive Front, the Baath Party–led coalition of legal Syrian political parties. (Al-Batal was eventually released without charge.)

Damascus is a mixture of normal and abnormal. Regime loyalists and opponents alike are relieved that mortars from the suburbs, from which rebels have now been evacuated, no longer explode in the metropolitan area. The army has dismantled many of its checkpoints. Schools and businesses are functioning, albeit below pre-war capacities. The National Museum, with its historical treasures from several millennia, has reopened to the public. Restaurants and bars, for those who can afford them, are thriving. Some young people have turned away from politics to open music venues, art galleries, and cafés. Many exiles from rural areas who took refuge in Damascus to escape violence are returning to their now peaceful, if damaged, houses.

On the capital’s outskirts, where the rebels reigned for six years, the landscape resembles another planet. The UN reckons that in some areas up to 90 percent of the structures have been destroyed. The estimated 350,000 inhabitants who stayed in Eastern Ghouta following the insurgents’ departure for Idlib are free of the heavy government bombardment that leveled their homes, hospitals, schools, and businesses. But their ravaged neighborhoods lack basic services, and they must deal with contaminated water, which causes diarrhea and other ailments, while only half the schools and just one hospital are functioning.

Leaving a nightclub in Damascus on foot one night, I was stopped by young soldiers who asked for my passport. Beside them, a half-dozen youths in leather jackets and jeans stood in a circle while two older men inside a covered jeep inspected their identity cards. One, avuncular in rimless glasses slipping down his nose, tapped ID numbers into a cell phone and waited for a response from headquarters. The boys who had already served in the army, or were exempt from service as the only sons in their families, were free to go. The rest had to report to recruiting stations later in the week. Fear of conscription keeps thousands of young men outside the country, even when their families return.

Advertisement

Continued conscription is one sign that the government has not abandoned the military option of reclaiming occupied territories. The most problematic region is the north, where Turkey is entrenching itself as it did in northern Cyprus following its occupation in 1974. About half of Idlib province’s population of 2.5 million, as estimated by the International Committee of the Red Cross, are original inhabitants, and half are exiles from other Syrian regions. Turkey, while ethnically cleansing Kurds from Afrin, is injecting its culture, governance, and economy into the lives of north Syrian Arabs. Schools have begun teaching Turkish. Bilingual Turkish and Arabic signposts are going up on the roadways. Posters in the Turkish-occupied town of Azaz declare, “Brotherhood has no limits.” Turk Telekom has replaced the Syrian cell phone network. In Afrin, a formerly Kurdish town, the Turkish Post Telephone and Telegraph (PTT) has moved into the old Syrian post office, and letters are sent with Turkish stamps. Turkey is exporting to Idlib and Afrin the foodstuffs, furniture, and textiles that previously came from other parts of Syria.

While many Sunni Arabs in the north appear content with Turkish hegemony so long as it maintains order, the occupation is intolerant of expressions of Syrian nationalism. Moreover, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s threat to destroy the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (known by their Kurdish initials YPG), which forms the backbone of what the US calls the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), could lead to the vast expansion of the Turkish occupation zone eastward along the six-hundred-mile border—especially when US forces withdraw. This would give Turkey control of the Kurdish-held zones of Kobane and al-Hasakah Governorate, which juts like a thumb northeast into Iraq and Turkey up to the Tigris River. Erdoğan’s army has regularly shelled the SDF’s positions there, despite the Kurdish-US alliance.

Damascus retains the option, so long as it refrains from directly confronting Turkey’s more powerful army, of destabilizing the occupation as it did with the Israelis in south Lebanon from 1982 to 2000. Suicide bombings, roadside attacks, kidnappings, and assassinations are tools that worked once and may work again. Assad’s allies will no doubt include the Kurds, who hate the Turks even more than they do Assad and favor Turkey’s expulsion from Syria—as do most Armenians and Christian Arabs. Hezbollah can provide hard-earned expertise from its guerrilla war against Israeli soldiers in Lebanon.

Damascus, though, feels like a city that has relegated war to the past. A friend who favored the opposition told me he congratulated a regime supporter on his side’s victory. The man, a Christian, refused to gloat. “It will start again in five or ten years,” my friend recalled him saying. “I’ve sent my family to Canada, and I am leaving too.” Some of the losers seem content with their defeat. A Sunni fundamentalist told another friend of mine that he was going into business with a member of Assad’s minority Alawite sect. To my friend’s surprise he explained, “I’ll do business with anyone. Maybe he can’t marry my daughter, but money has no religion.”

On the morning I left Damascus, I stopped at the Fardoss Tower Hotel’s ground-floor café. It was the hectic hub in 2012 for young activists organizing demonstrations, writing manifestos, and explaining their goals to journalists. They now seem a bit like the college kids who had learned about politics working on Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1968 before reality struck with his assassination and the Chicago cops’ billy clubs at the Democratic Convention. The café was deserted, its walls repainted in subdued beige. A wide-screen television played vapid music videos, and a waiter sat in silence behind the bar. Floor-to-ceiling windows revealed crowded sidewalks where Syrians of all classes and sects were rushing to schools, offices, and restaurants; drivers perpetually honked their horns; and languid policemen ignored the traffic. Syria is returning to what it was before the war. The war’s causes—corruption, political repression, rural neglect, and economic disparities—have not been addressed, and the victors know that somewhere someone waits to topple the statues again.

—January 10, 2019