From the ill-conceived Brexit referendum onward, Britain’s governing class has embarrassed itself. The Remain campaign was complacent, the Leave campaign brazenly mendacious, and as soon as the result was known, most of the loudest advocates for severing ties with the European Union ran away like naughty schoolboys whose cricket ball had smashed a greenhouse window. Negotiations have revealed the pitiful intellectual limitations of a succession of blustering cabinet ministers, the leader of Her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition doesn’t appear to want to oppose, and the prime minister has engineered her own humiliation by starting the countdown to Brexit without a plan that could command wide support, resulting in the heaviest parliamentary defeat in history. Despite breaches of campaign finance limits and lingering questions over the source of the Leave campaign’s financing, not to mention growing evidence tying it to the same web of influence operations that promoted Trump’s candidacy, there is no equivalent to the Mueller inquiry to bolster public confidence that the organs of state are capable of warding off corruption.

Britain is a country under self-inflicted stress, gripped by fear of the unknown. Remainers and Leavers—two tribes that have taken on the mythic stature of Roundheads and Cavaliers in a second civil war—are clinging together like drowning swimmers, each side convinced that the other is provoking an epochal disaster, neither side understanding why the other won’t submit to its version of reason and allow itself to be guided back to the surface. As the deadline approaches and the clock runs down toward the “No Deal” outcome that was supposed to be unthinkable, the divided nation faces what is, by any standards, a major political crisis. However, as British people like to remind one another, we are supposedly at our best in a crisis.

On December 16, the former Brexit secretary Dominic Raab tweeted, “Remainers believe UK prosperity depends on its location, Brexiters believe UK prosperity depends on its character.” Faith in Brexit does indeed seem to correlate with belief in the existence of national character, an innate and invariant set of shared qualities that apparently includes an aptitude for governance. On December 30 an editorial in London’s Sunday Times spluttered:

After more than four decades in the EU we are in danger of persuading ourselves that we have forgotten how to run the country by ourselves. A people who within living memory governed a quarter of the world’s land area and a fifth of its population is surely capable of governing itself without Brussels.

The many unanticipated problems with Brexit are diagnosed by the Sunday Times writer as a loss of confidence, perhaps accompanied by a faulty memory—something happening not just to people but to “a people.” The implication of the indefinite article, with its baggage of Romantic Nationalism, is clear. Britons, as Rule Britannia triumphantly puts it, “never, never, never shall be slaves.” The underside of nostalgia for an imperial past is a horror of finding the tables turned. For the more unhinged Brexiteers, leaving the EU takes on the character of a victorious army coming home with its spoils. In December 2017 Edward Leigh, a rosy-faced Tory backbencher, suggested in the House of Commons that an important negotiating point should be that the British “take back control of our fair share of [the EU’s] art and wine and not leave it for Mr. Juncker to enjoy.”

The battle over Europe has been fought not over the technicalities of the “Irish backstop” (maintaining the open border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland), NHS funding, or traffic flow through Dover, let alone harmonized airline regulations or the trading benefits of a Canada-plus model (along the lines of the one Canada signed with the EU in 2016, following seven years of negotiation), but through Spitfires, Cornish pasties, singing “Jerusalem” on the last night of the Proms, and what the Irish historian and journalist Fintan O’Toole calls “the strange sense of imaginary oppression that underlies Brexit.” O’Toole’s Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain is an acid and entertaining examination of what he calls, after the scholar Raymond Williams, the “structure of feeling” that has made the project of leaving the European Union politically possible.

O’Toole knows England (and Brexit is primarily an affair of England, the English, and Englishness) as only a member of the former subject races can. He starts his book with an account of arriving in 1969 to live in London as an eleven-year-old Irish Catholic boy, explaining how his family’s experiences, good and bad, complicated the cartoonish opposition to Englishness that characterized popular Irish nationalism: “The English were scientific rationalists; so we Irish had to be the mystical dreamers of dreams. They were Anglo-Saxons; we were Celts….In other words, I know exactly what an either/or identity looks and feels like.” O’Toole has not come to gloat, though many others around the world are doing just that. He writes in the tone of a disappointed friend, perhaps one sitting in a front room with other friends and family, conducting an intervention.

Advertisement

One prong of O’Toole’s approach is psychological. He quotes Herbert Spencer on self-pity as a person’s pathological “dwelling on the contrast between his own worth as he estimates it and the treatment he has received.” This disparity is founded on an underlying narcissism: “One who contemplates his own affliction as undeserved necessarily contemplates his own merit…there is an idea of much withheld and a feeling of implied superiority to those who withhold it.” The other prong is historical. Starting from “the sheer exhilaration of being English for a young, white, privileged man during and after the war,” O’Toole tells the familiar story of an imperial decline that has gradually ratcheted up the tension between this “deep sense of grievance and a high sense of superiority.” As early as 1962, the travel writer James Morris lamented the passing of a “feeling of happy supremacy,” which meant that “frank pride of country has all but gone by the board, and patriotism is very nearly a dirty word.”

In Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, one of a body of thrillers that are also among the most acute literary portrayals of the British establishment’s experience of postwar decline, John Le Carré’s hero, George Smiley, goes to see Connie Sachs, a motherly drunk who was once a secret service librarian and is now a repository of institutional secrets. “Poor Loves,” she says of George and his colleagues, her “boys.” “Trained to Empire, trained to rule the waves. All gone. All taken away. Bye-bye, world.” Many of those who took it away were, of course, foreigners, particularly those former colonial subjects who unaccountably agitated for decolonization. Their arrival “over here” was one of the most visible changes to postwar Britain, and as O’Toole points out, the rhetoric—“swamping,” being a stranger in one’s own country, strain on public services, and so on—that was once used to demonize new arrivals from the Commonwealth has been repurposed for use on EU migrants. O’Toole argues provocatively that the decline of what might be called traditional British racism made room for a new anti-Europeanism, as if there’s a fixed national quantum of xenophobia that must find an object if the United Kingdom is to maintain its integrity.

Though the Suez Crisis and imperial decline loom large in the imagination of Brexit, O’Toole writes that it’s “the war” that is “crucial in structuring English feeling about the European Union.” For half a century, English soccer fans have lamely taunted their more successful German counterparts by chanting that their country has won “two World Wars and one World Cup.” Since the 1960s, comic books with names like Commando, Warlord, and Battle Picture Weekly have kept World War II alive in the minds of British boys with violent stories of “daring bomber raids over Germany, through close-combat jungle fighting against hard-as-nails Japanese, and depth-charge blasted submarine warfare, to hard-hitting battles across North Africa, Italy and northern Europe.” The need for an enemy and the narrative of the plucky island nation resisting invasion is summed up by the famous David Low cartoon, first published in the Evening Standard in June 1940, of a Tommy standing amid crashing waves, shaking his fist at a stormy sky. “Very well, alone” is the caption, and it inaugurates a continuing psychodrama of resistance that sets Britain apart from its European neighbors.

Crucially, the equation of a “European superstate” with a project of German domination is part of what O’Toole calls the “mental cartography” of English conservatism. In 1989 Margaret Thatcher showed François Mitterand a map (taken out of her famous handbag) outlining German expansion under the Nazis, in order to demonstrate her misgivings about German reunification. On January 7 of this year, the pro-Remain Conservative MP Anna Soubry was forced to pause a live TV interview outside Parliament as protesters sang, “Soubry is a Nazi, Soubry is a Nazi la-la-la-la.” The European Union is, to these people, just a stealthy way for the Germans to complete Hitler’s unfinished business.

Of course, the British population did suffer in World War II. Aerial bombardment, rationing, and the other dangers and privations that are remembered under the journalistic heading of “the spirit of the Blitz” swim through the murkier psychological currents of Brexit like red-white-and-blue carp. If wanting to remain under the Teutonic yoke of the European Union is evidence of a loss of national character, then perhaps a fallen England deserves to be punished. As O’Toole suggests, invoking the popularity of the book Fifty Shades of Grey, a strain of masochism (le vice anglais) is as much a part of Englishness as warm beer or ruling the waves.

Advertisement

As the possibility of No Deal looms larger, the government is planning to import emergency supplies of food and medicine, and police are being deployed in expectation of civil unrest in Northern Ireland. These are not the “sunlit uplands” that our dollar-store Churchills promised. Faced with the possibility that the coming hour will not be our finest, some Brexiteers have switched to promoting the benefits of communal suffering. Perhaps renewed bombardment will turn out to be character-building. Perhaps the Euro-Luftwaffe will drop the “friendly bombs” that John Betjeman once willed to fall on Slough, to “get it ready for the plough.” On December 16, Anthony Middleton, a former special forces soldier turned TV personality, tweeted:

A “no deal” for our country would actually be a blessing in disguise. It would force us into hardship and suffering which would unite & bring us together, bringing back British values of loyalty and a sense of community! Extreme change is needed! #nodeal #suffertogether.

Though widely derided, this opinion is, in certain circles, something of a commonplace. In his yearning for a cleansing fire to burn away the disloyal and revive a lost organic community, Middleton displays a disturbing protofascist mindset. The idea that the suffering of No Deal Brexit would be fairly shared is, of course, transparently absurd. A primary driver of Brexit, both among ordinary voters and among the political and business elite, is the desire to circumvent “regulation” in the form of European legislation on workers’ rights and safety, and to prevent appeals to the European Court of Human Rights. Brexit would cement the changes that took place after the 2008 crash, which was the pretext for a reduction of the social safety net under the guise of so-called austerity. The aim is to remake Britain as a “buccaneering” (for which read “predatory”) low-tax, high-risk place, a sort of reset to the pre-1945 world, before the inauguration of the welfare state and postwar social democracy. Nothing about the political complexion of its proponents suggests an ambition to build community of any kind.

Yet the desire named “Brexit” may not straightforwardly be for victory and the spoils of victory, but for its very opposite. O’Toole surveys the English cult of heroic failure, exemplified by the charge of the Light Brigade and the evacuation from Dunkirk, as well as such mythologized figures as Scott of the Antarctic and Gordon of Khartoum. He sees the exaltation of effort and vain self-sacrifice as “an exercise in transference,” arising paradoxically out of British power. The British of the Victorian period “needed to fill a yawning gap between their self-image as exemplars of liberty and civility and the violence and domination that were the realities of Empire.”

On this reading, the secret libidinal need of Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Michael Gove, and their colleagues is actually for their noble project to fail in the most painful way possible. The immolation of national wealth and prestige on the altar of Brexit would be an imperial last stand, a way to recapture the spirit, if not the material conditions, of the Victorian apogee of British power. In this way, Brexit would provide a resolution to a problem that, in O’Toole’s diagnosis, has dogged the “poor loves” of the English ruling class since decolonization: “Its promise is, at heart, a liberation, not from Europe, but from the torment of an eternally unresolved conflict between superiority and inferiority.”

For many commentators writing at the time of Britain’s entry into the Common Market in 1973, dominance in Europe was to be compensation for the loss of empire. “What about Prince Charles as Emperor?” asked Nancy Mitford, facetiously expressing the secret belief of many British people that Europe could be a new vehicle for old global ambitions. The discovery that the role of “first among equals” wasn’t on offer led to a loss of enthusiasm for Europeanism, which suddenly appeared in a different and sinister light, as a form of subordination to old enemies.

How has what is essentially an English psychodrama turned into an international crisis? Against Dominic Raab’s John-Bullishness about the verities of national character, we might put W.H. Auden’s tongue-in-cheek notion that this character has been formed by place, or, more precisely, by geology. His 1948 poem “In Praise of Limestone” is a mock encomium to a soft and porous rock and the soft and porous men formed by its landscape. Auden’s self-ironizing “we, the inconstant ones” skewers perfectly the limitations of an elite that has historically adopted what O’Toole calls “a studied ennui, a pose of perfect indifference”:

…the flirtatious male who lounges

Against a rock in the sunlight,

never doubting

That for all his faults he is

loved; whose works are but

Extensions of his power to

charm…

Or the “band of rivals” who are

unable

To conceive a god whose

temper-tantrums are moral

And not to be pacified by a

clever line

Or a good lay…

This patrician fecklessness is one of the most enduring modes of British upper-class charisma, a way to signify superiority over the rule-governed, bean-counting strivers of the bourgeoisie. O’Toole correctly identifies it as a type of camp, allowing mistakes to be laughed off and ignorance to be presented as a virtue, evidence that one is not “touched” by the matter at hand. The English public’s fatal attraction to this posture has been responsible for many otherwise inexplicable political careers. Boris Johnson’s improbable upward trajectory is, for example, entirely due to his pitch-perfect performance in the stock role of the rakish comedy toff, a figure whose avarice and incompetence is indulged because it is somehow enjoyable to watch him getting away with things. It is no accident that the paradigmatically childish image of “having one’s cake and eating it” has been central to Johnson’s promotion of Brexit. As O’Toole notes, even his racism is couched in the language of the nursery. His notorious reference to “flag-waving picaninnies” with “watermelon smiles” is like a phrase from the kind of old-fashioned children’s books that are being quietly withdrawn from the library.

It is Britain’s misfortune to have been ruled by such people, entitled men who don’t feel they need to master a brief and sneer at those who have to endure the consequences of their actions. The form of patriotism they have promoted with their shallow, friable charm is less a spur to excellence than a form of historical arrested development, an adolescent inability to live in the world as it is, rather than a version of it misremembered from schoolbooks. O’Toole lays much of the blame for the fiasco of Brexit on the failure of the political elite to address the rise of English nationalism, which grew in intensity during the early 2000s, partly in response to Scottish devolution. Englishness—“its roar,” as the poet Thom Gunn wrote, “unheard from always being heard”—has, with good reason, become associated with ugly racism and xenophobia. Particularly strong outside London, English nationalism has also become an identity of resistance to globalization, a process that has accelerated the disconnection of the capital’s fortunes, which are dependent on finance, from those of the rest of the country. Brexit has offered a credible political vehicle for the assertion of “Englishness” against a “Britishness” that has lost its emotional appeal, a sudden scream after a period of what O’Toole calls “silent secession.”

The English, whose opinions have been formed by the shallow charmers and their enablers, seem fundamentally unable to conceive of a relationship with Europe that is not one of either subjection or domination. They will try, one way or another, to regain what Enoch Powell called “the whip hand,” even if they have to immiserate the country to do it. The principle of equal partnership on which the European Union is predicated is somehow psychologically unavailable, a possibility that is not fully believed or understood. The prolonged agony of Brexit has given ample proof that, as Auden wrote, “this land is not the sweet home that it looks,/Nor its peace the historical calm of a site/Where something was settled once and for all.” In the next few weeks, we will find an answer to his lingering question about its identity:

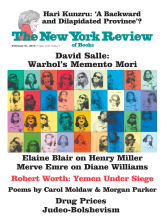

A backward

And dilapidated province,

connected

To the big busy world by a tunnel,

with a certain

Seedy appeal, is that all it is now?

—January 24, 2019