Pity John Burnside. It’s not the best time to publish an appreciation and defense of Henry Miller, whose Tropics trilogy, written in the 1930s, was banned for decades in the US for obscenity, and then indicted by feminist critic Kate Millet in her book Sexual Politics (1970) as a paramount example of chauvinist attitudes toward women. Burnside, a poet, points out that Miller is a romantic who devoted over a thousand pages (the Rosy Crucifixion cycle) to chronicling his narrator’s relationship with the great love of his life (based on Miller’s second wife, June). More specifically, Miller was one of the early-twentieth-century writers—with Lawrence and Joyce—who brought the explicitly carnal, so-called lower functions into the literary language of heterosexual romantic love.

Written in an autobiographical first person, Miller’s dirty books are intimate and ardent. “O Tania, where now is that warm cunt of yours, those fat, heavy garters, those soft, bulging thighs? There is a bone in my prick six inches long. I will ream out every wrinkle in your cunt, Tania, big with seed,” Miller’s narrator croons in his infamous address to a married lover in the opening pages of Tropic of Cancer—reason alone for the book to be unpublishable in his home country until 1961, when it was vindicated as a legitimate work of art in an obscenity trial.

I shoot hot bolts into you, Tania, I make your ovaries incandescent. Your Sylvester is a little jealous now? He feels something, does he? He feels the remnants of my big prick. I have set the shores a little wider, I have ironed out the wrinkles. After me you can take on stallions, bulls, rams, drakes, St. Bernards. You can stuff toads, bats, lizards up your rectum. You can shit arpeggios if you like, or string a zither across your navel. I am fucking you, Tania, so that you’ll stay fucked.

It may be hard to hear the romance and dash of Miller’s address when parts of it (“I will ream out every wrinkle in your cunt”) sound like something an angry gamer might have tweeted to Brianna Wu, the video game developer who received numerous threats after criticizing the sexist nature of her industry (actual example: “I’ve got a K-bar and I’m coming to your house so I can shove it up your ugly feminist cunt”). Fifty years after the last obscenity trials cleared the way for sexually explicit content in art, Miller’s writing still violates community standards, as they say, but for a reason other than its being explicit. Alongside our general acceptance of sexual and profane language, a public language of violent, misogynist intimidation has also arisen. “Take her off the stage and fuck her,” some men from Students for a Democratic Society jeered while Shulamith Firestone was speaking about women’s issues at a New Left anti-Nixon rally in 1969. In 2015 Samantha Bee, who was about to become the first woman to have her own late-night show, joked that she’d created a separate “rape threatline” for all the people sending her sexually violent comments. “Whore” doesn’t have much power as a dirty word, but it does have startling power as the last word in Kristen Roupenian’s story “Cat Person,” texted by a man whose attitudes toward the main character have been ambiguous and freighted with potential menace.

Our contemporary obscenities are the racist, sexist, homophobic language of hate speech, language that reminds us of our ability—our desire, we have to conclude—to dismiss and brutalize whole categories of people. Hate speech is of course not banned within works of art, but its usage is contested depending on who’s speaking in what context. A wish to ream out every wrinkle in someone’s cunt is, for today’s reader, possibly as vexing an expression of heterosexual love as it was when Miller wrote it, “cunt” occupying that narrow, cunt-shaped part of the Venn diagram where explicitly sexual terms overlap with terms of potential hate speech, where the old obscenity is also the new obscenity. “Cunt” can’t get a break. For similar reasons, neither can Henry Miller.

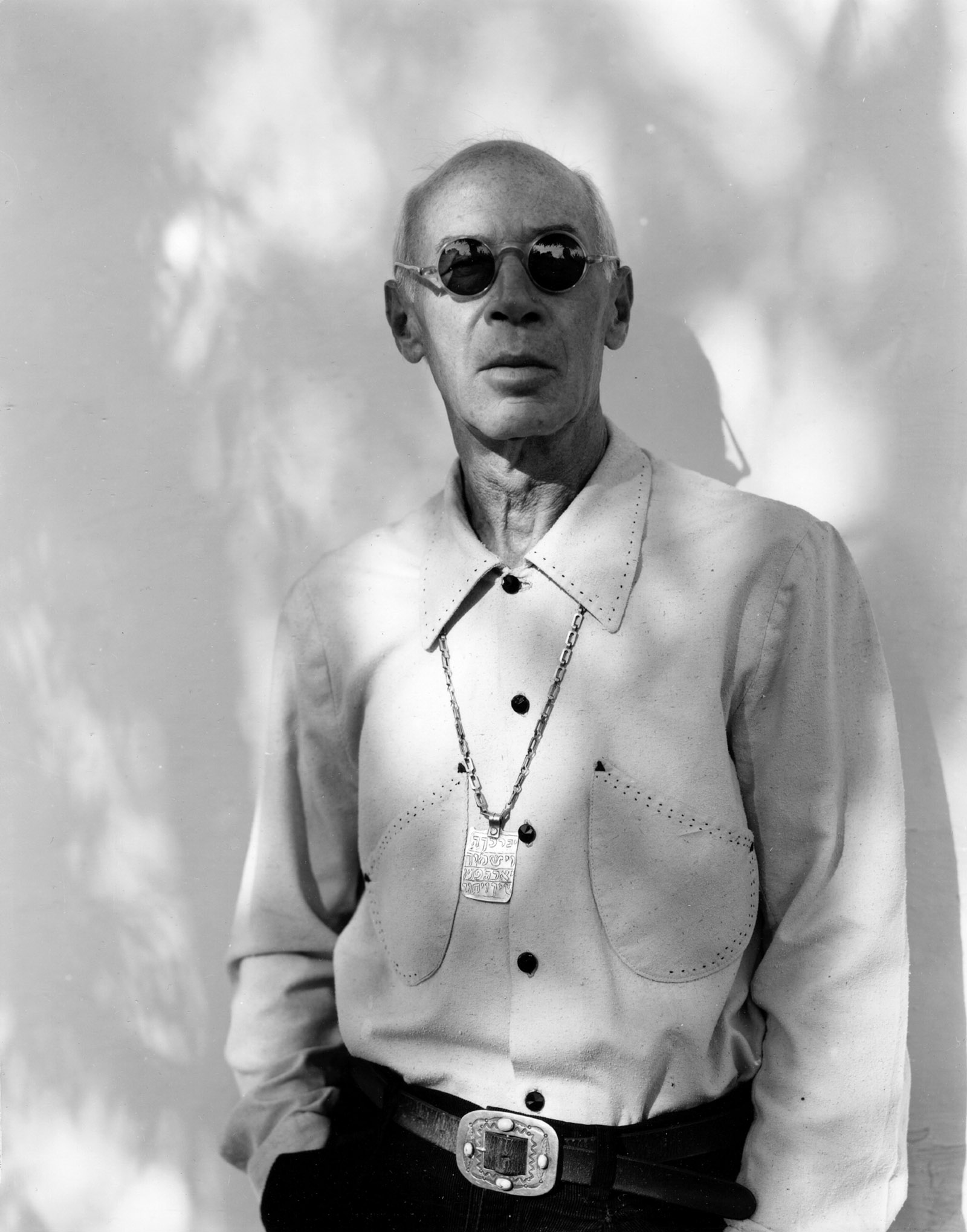

To generations of American readers who got their hands on a forbidden copy of Tropic of Cancer, Miller’s voice sounded like freedom itself. Miller was born in 1891, the son of a tailor, and grew up in a lower-middle-class German-American family in Brooklyn. Until his forties he lived mostly in New York (with short stints in California and the South) and wrote prolifically but fruitlessly for decades, supporting himself with a variety of jobs until he came to rely entirely on June, who found them patrons by striking up flirtations with rich-ish men at the dance hall where she worked as a waitress and dancing girl.

Advertisement

Despite June’s belief in his genius, his stories and novels weren’t coming out right, and publishers weren’t interested. (At this stage, he was writing third-person, lightly fictionalized accounts of his day job as a personnel manager at Western Union and his relationship with June, material he would later rework for Tropic of Capricorn and The Rosy Crucifixion.) He left for Paris as a last-ditch effort to change things up, make something happen with his writing. He bummed around Montparnasse, cadging meals, cash, and living quarters from other artists and a few sympathetic benefactors—and from June, who wired him money from New York.

The escape trick worked. At the age of forty, he found a way to write that sounded true. First-person, loosely autobiographical, freewheeling, drawing on such various guiding spirits as Whitman and Céline (whose Journey to the End of the Night Miller read in manuscript while working on Tropic of Cancer), Miller’s Paris novels did away with a lot of the narrative machinery that he saw, in retrospect, had been weighing down his earlier work. Tropic of Cancer is about the narrator’s vagabond life in Paris, the city that had recently worked its magic and set his voice free. The discovery of his writing voice is an event that feels so big that Miller casts it as a renunciation, a total break with his past, a break—in the going style of modernist grand gestures—with literature itself: “Everything that was literature has fallen from me. There are no more books to be written, thank God.” But Miller was not a revolutionary or a movement man. He was a writer finally settling down to play. As George Orwell wrote, Tropic of Cancer “is the book of a man who is happy.”

Orwell too was once poor in bohemian Paris, and wrote of the peculiar satisfaction of hitting bottom:

It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often of going to the dogs—and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.

Orwell’s narrator in Down and Out in Paris and London gives the sense of having taken the exact measure of a situation, seen it clearly, described it precisely. Having nailed it, he goes to look for a job.

Miller’s narrator, by contrast, doesn’t describe, he sings. “I have no money, no resources, no hopes,” he tell us on the first page—“I am the happiest man alive.” Though he too will eventually get a job (as a newspaper proofreader), he will first revel in finding himself at the bottom:

My last problem—breakfast—is gone. I have simplified everything. If there are any new problems I can carry them in my rucksack, along with my dirty wash. I am throwing away all my sous. What need have I for money? I am a writing machine. The last screw has been added. The thing flows.

His narrator drinks, writes, gains and loses small amounts of money, has sex with Tania, with whores, and with his wife when she visits from the States. He makes the social rounds in Montparnasse, among the artists, grifters, Russian exiles, and would-be writers. The book is full of comic incidents and anecdotes unfolding in a continuous present. The big thing that happens to the narrator—his finding a way to write—has already happened at the start of the book, and in any case it can’t be narrated directly. All the book can do is point to the conditions that enabled the narrator’s newfound freedom: his exile, his poverty, his submission to the waywardness of his life, his going with the flow. In Tropic of Cancer’s last scene, the narrator, temporarily flush with cash, takes a cab to a beer garden for a drink by the Seine: “The sun is setting. I feel this river flowing through me—its past, its ancient soil, the changing climate. The hills gently girdle it about: its course is fixed.”

Miller proceeds by colloquial exaggeration, hyperbole, and provocative overstatement, spiced with earthy frankness and surreal comic metaphor:

It was only this morning that I became conscious again of this physical Paris of which I have been unaware for weeks. Perhaps it is because the book has begun to grow inside me. I am carrying it around with me everywhere. I walk through the streets big with child and the cops escort me across the street. Women get up to offer me their seats. Nobody pushes me rudely any more. I am pregnant. I waddle awkwardly, my big stomach pressed against the weight of the world.

We are so used to the first-person comic-oratorical (thanks in part to Miller himself) that it hardly needs explanation today, but no one had quite done it like that in English before. He dares us to disbelieve him, knowing full well he has gotten at the truth without having taken the exact measure of anything at all. Measuring is for bureaucrats. “Even if my distortions and deformations be deliberate, they are not necessarily less near to the truth of things,” Miller wrote several years after completing the Tropics, in an essay called “Reflections on Writing.” “One can be absolutely truthful and sincere even though admittedly the most outrageous liar.”

Advertisement

After he moved back to the US and settled in Big Sur in 1944, Miller had a steady trickle of visitors—pilgrims, really—mostly young white men in flight from middle-class ideals or working-class dead-end jobs, who had been moved by his books to reconsider their ways of life. By this time Miller, an anarchist since his twenties, had not only published the Tropics novels and Black Spring, but also several books of critical and personal essays in which he laid out a worldview that valorized individual liberation from social rules, materialism, and spurious national values, while advocating the pursuit of inner freedom and a self-guided life. Tropic of Capricorn’s narrator dreams of a stateless, lawless, borderless world, a vision more suggestive than prescriptive, where “you wouldn’t own anything except what you could carry around with you and why would you want to own anything when everything would be free?” Miller wrote numerous essays and passages in his novels broadly condemning Western culture, colonialism, capitalism, and the extraction of the earth’s resources. He also considered himself a kindred spirit of the Dadaists, and he captures more in his witty glancing riffs than in his broad direct attacks. Here is the fevered reverie of Tropic of Capricorn’s narrator on a cold night in New York:

To walk in money through the night crowd, protected by money, lulled by money, dulled by money, the crowd itself a money, the breath money, no least single object anywhere that is not money, money, money everywhere and still not enough, and then no money or a little money or less money or more money, but money, always money, and if you have money or you don’t have money it is the money that counts and money makes money, but what makes money make money?

Burnside, who loves and lives by some of the anarchist principles that Miller advocated, argues that “in an age of environmental crisis” these principles are newly relevant: “What we need, each of us, is to become our own anarchists—which is to say, unlearn our conditioning and refuse to be led, thus transforming ourselves into freethinking, self-governing spirits.” But Miller is vague on the question of how liberated spirits are to coexist, and Burnside doesn’t explain how we get from refusing to be led to the kind of large-scale collaboration that seems almost certainly required by the climate crisis. Miller’s vision doesn’t easily mesh with today’s skepticism toward personal transformation, or with the growing conviction that even the most productive and salutary forms of self-liberation can’t serve as substitutes for collective action.

Miller’s own inclinations, in any case, were strongly bohemian, and for most of his life he lived practically hand to mouth. After he and June divorced in 1934, he relied on handouts from Anaïs Nin (whose rich husband and rich psychiatrist-lover provided personal funds as well as financing for the European publication of Miller’s first book), from a few close friends, and from other supporters of his writing. He published short pieces in obscure, low-paying magazines, and he took up watercolor painting and sold his work for badly needed cash. He had a daughter from his first marriage whom he did not support (or see much of after the divorce) and two children with his third wife. Only when his books were published in the US in 1961, when he was seventy, did he finally make a comfortable living from his writing.

When Burnside decided to write about Miller, he tells us, he

had been thinking for some time what it means, not to write the odd poem or two, but to work as a writer, trapped in a seemingly unending struggle to render unto Caesar just enough to buy an hour or two each day to sit in a narrow room and confess, to a sheet of cold white paper, the inner workings of a botched heart.

Burnside—born in Scotland, growing up in England, the son of a steelworker in the East Midlands—had come to Miller’s books as a young man in the 1960s in search of permission and the validation of his desire to write:

Growing up, I had not intended to take up writing as a métier. In fact—as my father frequently told me, whenever I expressed an interest in anything other than manual labor or the armed forces—I knew all too well that “people like us” did not presume to “go into” the arts, where only one in a million “made it,” and that one in a million came from an entirely different background from the gray, uninspiring streets of the impoverished coal and steel towns where I was attempting, despite my father’s derision, to grow up as a different kind of man from the specimen he wanted me to be (tough, hard, ready for anything, devoid of trust).

Miller has so thoroughly been cast as a sexist writer, Burnside points out, that readers may not realize how much his writing upends the early-twentieth-century ideals of manhood that he would have grown up with—and that Burnside also grew up with, one generation removed:

My father’s notions of manliness were mostly to do with physical prowess and the ability to endure hardship—work, pain, mental fight—without complaint. Though he was somewhat younger than Henry Miller, he would probably have been exposed to similar idealizations of manly life, of the kind to which Theodore Roosevelt subscribed: “We need the iron qualities that go with true manhood. We need the positive virtues of resolution, of courage, of indomitable will, of power to do without shirking the rough work that must always be done.” What the industrial society wanted from my father was physical endurance in the coal mine or the steel mill, and reasonable courage in warfare. It had no use for his narrative gifts. Like Miller, my father saw through the societal rhetoric, but he did not know how to avoid his fate as a piece of industrial cannon fodder.

Miller’s own father was judged and hounded by his mother for being a failure at his business, a subject Miller elaborated in Black Spring and Tropic of Capricorn. Refusing his mother’s standards, obscurely keeping faith with his father, Miller too failed to earn a living—a circumstance that caused him some shame (especially with his parents) even as he flaunted it defiantly at other times. He did not, however, ultimately fail as a writer, and his belated, spectacular discovery of his voice allowed him to rewrite the story of supposed failure into a triumph over the tyranny of social expectations and economic pressures. You can be a man without property, he insisted, you can be a man without a wife (in the traditional, respectable sense of the word), you can be a man without a home, and you can be a man while talking about the pleasure of emptying your bladder in a Paris public urinal.

In Tropic of Cancer (unlike the subsequent books, where self-mythologizing and sexual bravado creep in), much of the sex is actually failed sex, or sex that doesn’t go the way it’s supposed to. The narrator and his friends are more likely to fail to get erections, or come at the wrong time, or in the wrong place, than they are to brag about a conquest. His friend Van Norden, the most ardent (we would say compulsive) seducer of women, tells a story of how one of his girlfriends shocked him by revealing that she had shaved her pubic hair:

His curiosity aroused, he got out of bed and searched for his flashlight. “I made her hold it open and I trained the flashlight on it. You should have seen me…it was comical. I got so worked up about it that I forgot all about her. I never in my life looked at a cunt so seriously…. And the more I looked at it the less interesting it became…. When you look at it that way, sort of detached like, you get funny notions in your head. All that mystery about sex and then you discover that it’s nothing—just a blank. Wouldn’t it be funny if you found a harmonica inside…or a calendar?

As a portrait of man vainly trying to trace his appetites to their source, this is pretty funny. By the end of the book, Van Norden—on whom the narrator looks with bemused, condescending fondness—gives up women, deciding it just as pleasing and more convenient to masturbate into a cored apple. But the episode isn’t simply about man, it’s about a man and a woman—who, by the way, is doing what while Van Norden is peering into her vagina? Laughing? Hating? Who knows. Miller’s highly subjective first-person (in this case, Van Norden’s first-person-within-first-person) allows him to write rich comedy about sex in which the woman need not be in on the joke.

Does Miller’s freethinking man have a counterpart in freethinking woman? Miller would surely have said yes—the kind of inner freedom he was after is by definition improvised, often in straitened circumstances, and therefore theoretically available to almost anyone yet difficult for almost everyone to attain. In his novels, however, he doesn’t much care to consider the particular matrix in which women had to make their choices and compromises with a moralistic, property-based, and patriarchal society. The novels are taken up with observing and articulating male ways of being in the world, male styles, male attitudes toward sex and love.

He is very good on men, especially the working men of New York making their way in an unforgiving city. There are great passages in the Tropics and Black Spring about the narrator’s father, the Brooklyn boys and men the narrator grew up with, the lowly bicycle messengers whom he was in charge of hiring and firing for a large New York company (based on Miller’s days at Western Union). The narrator’s manager at the company asks him to write “a sort of Horatio Alger book about the messengers,” sending the narrator into a fugue of indignation (he calls Horatio Alger “the dream of a sick America”) on behalf of the many desperately poor men he interviews who don’t have a prayer of advancing in the company: “You shits,” the narrator imagines telling his managers, “I will give you the picture of twelve little men, zeros without decimals, ciphers, digits, the twelve uncrushable worms who are hollowing out the base of your rotten edifice.”

Women also apply to be messengers at the company, but they inspire a different kind of feeling:

The game was to keep them on a string, to promise them a job but to get a free fuck first. Usually it was only necessary to throw a feed into them in order to bring them back to the office at night and lay them out on the zinc-covered table in the dressing room.

Miller believed in amorality when it came to sex. For him, “sexual morality” could only mean the prudery and hypocrisy and zealous oversight of his elders, which he hated. Nothing could be more foreign to Miller’s narrator than to have regret or misgivings about a sexual encounter based on a woman’s response or her circumstances. But the narrator’s commitment to sexual amorality leaves him unable to size up the plight of those would-be messengers who are both poor and female, or to perceive himself, when he exacts sex for the promise of job, as an instrument of that exploitative corporation that he derides.

Miller did not, in other words, see the subordination of women as one of his society’s many cruelties and stupidities. It could have been otherwise. He moved for some years in the Village bohemia of the 1920s before he left for Paris, in the setting where feminists and suffragists had mixed with other Progressives, anarchists, socialists, and artists of all kinds. Questions of women’s rights and status, alongside questions of free love, were still in the air. And for two centuries, most of the great Anglo-American novelists had been interested specifically in the question of how women could, or should, make their way in the world, given a set of sexual, social, and economic restrictions that would have seemed intolerable to men of the same class. But this was not Miller’s canon—he loved Rabelais, Boccaccio, Dostoevsky, Nietzsche—and these were not his questions.

Nonetheless, his books are full of female characters. Through his narrator’s social and sexual encounters with prostitutes, secretaries, teachers, dancers, desperate job applicants, and other men’s wives, Miller ends up showing us a great variety of women subject to the kinds of economic pressures, narrow prospects, sexual exploitation, and double standards elaborated—and lamented—by Samuel Richardson, Thomas Hardy, George Gissing, and Edith Wharton (most of whom were in their own time notably candid about sex). The difference and the shock of Miller is this: here is a novelist registering the same conditions that two centuries of great English-language writers taught readers to find absorbing, urgent, and unjust, but he has no moral response to them. He sees female characters from the other side, as it were, with cool indifference to their sense of themselves and to their fate, thus seeming to cut off a long-established, artistically fertile current of sympathy in prose fiction for the circumstances and constraints of people born female.

Van Norden’s—and the main narrator’s—attitude of essential aloofness from the woman with whom he’s having sex would be picked up in the work of many (heterosexual) writers and artists Miller inspired: it’s in Kerouac, in Lenny Bruce, in Mailer and Bellow and Roth, and in the work of later writers who make great comedy of male sexual appetites and failures. Miller became a guiding spirit of the 1960s sexual revolution, a movement whose public intellectuals and popular promoters—Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse, Hugh Hefner, and Helen Gurley Brown—ascribed sexual inhibition to a variety of sources (capitalism, property relations, bourgeois values, religion) without considering that a major factor in heterosexual sexuality might be what we now call sexism. They did not take account of the ways in which women’s lower status and limited scope for self-determination might also affect sexual expression—for all parties involved, and not necessarily for the better. The women’s movement would soon sweep in to correct them, and then get corrected itself through decades of intramural and extramural debate about sexual ethics.

There still sometimes seems a gap in our public discourse when it comes to these fault lines of heterosexuality, a hesitancy to suggest that the prevalence of sexual harassment, violence against women, and hiring discrimination have an effect not only on particular victims, but on intimate relationships between men and women. These relationships form and dissolve in a society that has long been sexually permissive without exactly being—or seeming, or feeling—sexually free. In his best flashes of writing about sex, Miller shows us how it might feel to be free and easy. But he can’t imagine what it would actually take to get us all there. Strange as it is to say, he did not think hard enough about women.

This Issue

February 21, 2019

The Fake Threat of Jewish Communism

The Star of the Silken Screen