In about 570 AD, in the dry hills of what is now northern Yemen, the great dam of Marib collapsed. It had been one of the engineering marvels of the ancient world, with a mud-and-brick retaining wall fifty feet high and 2,100 feet long—twice as long as the Hoover Dam. It fed a complex irrigation network that made the desert bloom and sustained the kingdom of the Sabaeans, who had built it, for more than a thousand years. The fertile plains around Marib were one reason the Romans called Yemen Arabia Felix, fertile or happy Arabia. After the dam’s collapse, the agricultural system failed and famine spread, setting off a mass migration of people.

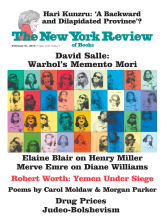

Yemen may now be approaching an equally historic catastrophe. After nearly four years of civil war between Houthi rebels and a Saudi-led coalition determined to restore to power the government of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, every month seems to bring some shocking new measure of civilian misery. Yemen now has the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, the worst cholera outbreak in recorded history, and among the highest rates of child malnutrition. An estimated 16 million people, more than half the country’s population, are threatened by starvation. During two weeks of reporting in September, I saw suffering on a scale I have rarely seen anywhere: overcrowded hospitals full of skeletal, starving children; makeshift camps of displaced people begging for handouts, many of them with war wounds; child soldiers on almost every street. Although the civilian death toll (roughly 50,000, though estimates vary widely) is dwarfed by that of Syria’s civil war, Yemen’s isolation, poverty, and barrenness pose a greater threat to the survival of its people.

In recent weeks, modest hopes for peace have been stirred by a United Nations–brokered cease-fire in the strategic port city of Hodeidah. The UN has sent monitors to bolster this shaky truce, which each side has accused the other of violating. The deal partly reflects a dramatic shift in global perceptions of the war’s primary architect, Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman. In an irony that was not lost on Yemenis, the murder in October of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi turned a spotlight on the deaths of thousands in the deserts of southern Arabia. Soon afterward, then Defense Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called for a cease-fire. In December the Senate voted to end the US policy, which began during the Obama administration and has continued under Trump, of providing intelligence, targeting, and logistics for the Saudi-led bombing campaign.

It is not yet clear how much pressure the Saudis are feeling, but there are signs that they may be willing to settle for less than total victory over the Houthis. Huge obstacles to peace remain, above all the Houthis’ military alliance with Iran, which is what led the Saudis to launch the war in the first place. Stopping the coalition’s bombing campaign would be an essential first step. But it may be too late to stitch the country back together. There are now dozens of local groups fighting and holding territory on at least a dozen front lines, and even a comprehensive peace settlement (which is still remote) might not dislodge them.

This pattern of wars-within-wars is most visible in the south of Yemen, which is nominally under the control of the Hadi government but is mostly ruled by factions allied with the United Arab Emirates, the other chief partner in the ten-member coalition the Saudis assembled in 2015. “There is no future for the centralized state,” I was told in September by Ahmed al-Misri, the interior minister of the largely symbolic government based in Aden, the decayed port city that was the center of the British colony in Yemen. Misri and his colleagues are determined to establish an independent state in the south, but their prospects seem remote; southern Yemen is a patchwork of different regional groups with a bloody history of internecine fighting.

Even within Aden, multiple groups vie for power, and assassinations and kidnappings are so common that my Yemeni friends warned me to stay indoors during my time there. I was able to drive safely through southern Yemen only because the checkpoints there are mostly controlled by Emirati-backed forces that have imposed a modicum of order. If those men are no longer paid by the UAE, they will seek other patrons whose interests are bound to clash. These myriad smaller conflicts, though less visible, may be more intractable than the big war now taking place.

In the north, where the Houthis run a police state of sorts, it is also far from clear what kind of authority would emerge after the war’s end. When I traveled in northern Yemen in September, the Houthis seemed in firm control. They have eradicated al-Qaeda in their areas, and I felt safer than I ever did in the days of Ali Abdullah Saleh, the longtime ruler who was deposed after the popular uprisings of 2011. In part, this is because the Houthis have benefited from popular resentment of the bombing campaign and the Saudi embargo, which blocks most humanitarian shipments of food or medicine. The Houthis have also shown remarkable military prowess. Their movement was forged during a series of wars against the Yemeni government between 2004 and 2010, and the bravery of their fighters is legendary.

Advertisement

Yet the Houthis are still new to politics. They belong to the Zaydi sect, an independent branch of Shiism, and their movement is profoundly religious; many Yemenis describe it scornfully as a “Shiite Taliban.” Although they cast themselves as victims, they have tortured and murdered many of their civilian opponents, and they allow no views critical of them to be aired in the media. A few brave demonstrations against their rule—quickly and forcefully suppressed—have suggested that a substantial undercurrent of anger might rise to the surface once the Saudis can no longer be blamed for Yemen’s ongoing trauma.

The magnificent old city in Sanaa, northern Yemen’s capital, with its drip-castle towers and curling medieval streets, has suffered only minor damage. Elsewhere, the scale of destruction is staggering. In the northwestern city of Sa’ada, where the Houthi movement first emerged, every government building has been destroyed by bombs. Those can be rebuilt; the greater loss is the medieval souk, a warren of mud-brick buildings where people once shopped in the shadow of a thousand-year-old mosque. I walked through the ruins with a twenty-three-year-old Houthi guide named Ali, who’d grown up a few blocks away. He pointed out the market stalls that had been imprinted on his memory since childhood: “Here there were dates and raisins,” he said, pointing to a shapeless mass of brown rubble. “Here was clothes. Here were big mills for grinding cereal and wheat. Here was the fish market.” Gone, all of it. A sign saying “King of Perfumes” was visible on the interior wall of an eviscerated stall. Collapsed ceilings hung down at odd angles. Piles of rubble and trash stood here and there, with local boys picking through them for anything that could be recycled.

If the fighting does end—or subside—attention will turn to the immense task of rebuilding what has been destroyed. The World Bank has unofficially estimated that Yemen’s reconstruction will cost $30 billion, but it is not likely to be a high priority, given the prospects for renewed conflict and the other war zones competing for attention around the Middle East. Yemen will probably be left to the mercy of Saudi Arabia, which has dominated it, in peace and in war, for a century. The Saudis have the means to help, but their motives often seem to be guided by the words that the kingdom’s founder, Ibn Saud, is said to have uttered on his deathbed: “Our power resides in Yemen’s humiliation, and our humiliation in Yemen’s power.”

It is easy to forget that not so long ago, Yemen was a byword only for backwardness and obscurity. In a 1998 episode of the sitcom Friends, one of the characters fakes a job transfer to Yemen to escape an unwanted girlfriend. Every time the word “Yemen” is mentioned, it is followed by canned laughter, as if the very idea of the country were a joke. That would soon change. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, Yemen began to acquire a sinister reputation as “the ancestral homeland of Osama bin Laden,” in the stock phrase used by the wire services. It was also the site of the attack on the USS Cole in 2000, in which seventeen American sailors were killed. (One of the attack’s planners, Jamal al-Badawi, was killed by an American airstrike in early January.) Within a few years, diplomats and journalists began showing up in Yemen (myself among them). The Bush and Obama administrations delivered unprecedented piles of money and weapons to fight al-Qaeda, and Saleh realized the group was a threat that could be turned to his advantage.

Laurent Bonnefoy, a young French scholar of Islamist movements, laments this narrow focus on counterterrorism in his new book, Yemen and the World. The threat posed by jihadi violence, he writes, has been persistently exaggerated. Between 2000 and 2008, about fifty people were killed by jihadists in Yemen, while during the same period thousands of people were killed in the Saleh government’s campaign against the Houthi rebels, including many noncombatants. The British academic Helen Lackner, who has been writing on Yemen for more than thirty years, makes the same argument in her book Yemen in Crisis, saying the West should have focused more on good governance and economic development in the country.

Advertisement

There is some truth in these complaints. But they disregard a central reality: until recently, the West’s aims were largely constrained by Saleh, a gifted manipulator whose power and reach allowed him to neutralize almost any foreign efforts that did not suit his short-term political needs. And while it is true that Yemenis often complain about the West’s obsession with counterterrorism, this is sometimes done to save face. More than once, I have heard Yemenis loudly denounce American drone strikes against suspected al-Qaeda members and then—after a few hours of tea and chewing qat—concede more quietly that al-Qaeda was a real danger, and that the drone strikes were a big improvement on the Yemeni military’s clumsy raids against it.

Although al-Qaeda persists in Yemen, it has been overshadowed by the Houthi movement, which has transformed itself in the past decade from an obscure rebel group into the country’s most powerful force. An air of mystery still hovers around the Houthis and their origins, and there is no better guide to them than Marieke Brandt, a German scholar who has done extensive fieldwork in northern Yemen. In Tribes and Politics in Yemen, we see how the Houthis—and the war that has embroiled the country for the past four years—cannot be understood without looking back at the traditional society that prevailed in Yemen until its republican revolution in 1962, and that has still not entirely faded away.

The Houthi movement’s leaders are descendants of a disenfranchised elite that once formed the top rung of an ancient caste system. The sada (the singular is sayyid), also known as the Hashemites, claimed descent from the Prophet Mohammad, a necessary qualification for the kings (known as imams) who ruled most of northern Yemen from the ninth century onward. Below the sada was a group called the qada’, or judges, and so on down to the akhdam, or servants, who are mostly of African descent and can still often be seen sweeping streets in the capital.

This caste system was abolished by the military officers who ousted the last imam in northern Yemen in 1962, in a coup inspired by Egypt’s revolution of a decade earlier. I know some elderly Yemenis who were among the cheering crowds in those early days, and they speak with intense nostalgia about their hopes that the revolution would secure equality, freedom, and dignity for all. What happened instead was a profound yet bitterly disappointing social transformation that paved the way for all of Yemen’s current problems.

Helen Lackner, who lived in Yemen in the early 1980s, provides a fascinating description of the shift from a traditional world where people were defined largely by their inherited status to a modern society dominated by money. The years just after the revolution were hopeful: the economy grew quickly, partly from remittances sent home by nearly a million Yemeni men working in Saudi Arabia. That came to a halt in 1990 when the Saudis—angered by Saleh’s support for Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait—abruptly kicked the workers out. The sudden collapse in household incomes coincided with the regime’s enrichment from newly discovered oil reserves. Saleh, meanwhile, built a patronage network that corrupted the tribal system and its values, and made everyone reliant on handouts from his regime in Sanaa.

A somewhat parallel transformation took place in southern Yemen, despite its vastly different history. After the British abandoned their colonial outpost in Aden in 1967, a Marxist regime took power and became a Soviet satellite. Its leaders dismantled old social identities more aggressively than the north had, abolishing the full female veil known as the niqab and ejecting feudal landowners. Lackner goes a little easy on the Leninists of South Yemen, who were given to dragging clerics on ropes behind cars and inviting terrorists (such as Carlos the Jackal) to train on their territory. Their economy was a shambles, and the state was utterly dependent on Soviet largesse.

After North and South Yemen unified in 1990, the southerners belatedly realized that Saleh, who had been president of North Yemen since 1978 and became president of the united country, never intended an equal partnership. They rebelled in 1994, and Saleh quickly subdued them with the help of irregular jihadi brigades who’d fought in Afghanistan. It was the start of a back-door relationship between Saleh and Islamists that would further poison Yemeni politics.

One consequence of the 1962 revolution was that the old quasi-royal caste—Zaydis of sada lineage—experienced a reversal in status and were now scorned as a symbol of the medieval past. A second blow came in the early 1980s, when the Saudis ramped up a campaign to promote their own puritanical strain of Sunni Islam, often called Wahhabism, in Yemen’s Zaydi heartland. The Saudis, fearing that Iran’s 1979 revolution might spread Shiism to their Yemeni neighbors, funded hundreds of religious schools in Yemen known as “scientific institutes” to pre-empt both social and Iranian influence. Many Zaydis saw the Saudi efforts as an assault on their religion and their way of life. Within a few years, their resentment helped give birth to a Zaydi revivalist movement in the mountains of the Sa’ada province in the northwest, the bastion of the old order, and a new political party was formed.

Among the movement’s leading figures was a revered religious scholar named Badreddin al-Houthi. One of his sons, Hussein al-Houthi, was a charismatic and conspiracy-minded zealot who tapped into popular anger across the Arab world against Israel and the United States. He came up with a slogan, better known in Yemen as the sarkha, or scream, that helped to define the Houthi movement: “God is Great, Death to America, Death to Israel, a Curse on the Jews, Victory to Islam.” Marieke Brandt suggests that Hussein first uttered the sarkha during the second Palestinian intifada in 2000, but I was told by Daifullah al-Shami, a high-ranking Houthi figure who knew Hussein well, that the slogan was a response to the September 11 attacks.

One thing is certain: Hussein used the sarkha to provoke Saleh, who had rushed to embrace the Bush administration’s war on terror despite his own history of aligning with Islamists and other anti-American figures. The sarkha made Saleh look like a hypocrite and opportunist, and he was furious. He soon cracked down on Hussein al-Houthi and his allies, and within three years a brief war broke out in which Hussein was killed. More wars followed. The Yemeni military’s widespread abuses and mistakes elicited sympathy for the Houthis among the northern tribes, allowing the movement to survive and grow even stronger.

Ever since the Houthis first emerged, their enemies have accused them of wanting to turn back the clock and revive North Yemen’s ancient hierarchies. They have always dismissed those charges as absurd. When the Arab Spring revolts began in 2011, the Houthis sent representatives to Sanaa and made common cause with the protesters camped out in what became known as Change Square. They said they stood for human rights, democracy, an end to corruption, and a more equitable distribution of Yemen’s wealth. A year after Saleh was forced to resign in early 2012, the Houthis took part in the National Dialogue Conference, which was meant to forge some sort of compromise about Yemen’s future political direction.

Yet even as the delegates talked—to the delight of foreign diplomats—the Yemeni state was dissolving in the far north, and the Houthis picked up the slack. The period from 2011 to 2014, Brandt writes, “was marked by an enormous territorial expansion of the Houthi dominion, made possible by military coercion, astute political activism at national level, shadowy deals, and adjustment and renegotiation of alliances.” Yemen had never had a sectarian divide; Zaydis, who make up about a third of the population, prayed in the same mosques as the majority Sunnis. But as the Houthis grew stronger, their enemies began casting them as Shias aligned with Iran.

As Yemen collapsed into chaos in the years after 2011, it was hard not to wonder if part of the Houthis’ appeal lay in the public’s deep disenchantment with everything that had happened since 1962. The grand hopes for democracy and freedom had been betrayed so thoroughly, both in the socialist south and the republican north, that some Yemenis wondered whether the whole project was misconceived. And the Houthis had an answer: they seemed to offer an alternative to modernity, a connection to Yemen’s deeper history that some people found reassuring. The speeches of their clerics and their leader, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi (brother of the late Hussein), and even their rhetoric about corruption suggest a divine sanction for their rule. This was partly a matter of Zaydism itself, which originated in an eighth-century rebellion against a corrupt autocrat. Ever since, one of the Zaydi sect’s core principles is that the faithful have an obligation to rise up in revolt against unjust rulers. But the Houthis were not just offering a return to the past. They have adapted traditional Zaydism to their own ends, making it a more political faith with certain echoes of the revolutionary Shiism that reigns in Tehran and southern Lebanon. This accounts for much of the fear they arouse in Saudi Arabia.

Any claims the Houthis may make to popular legitimacy are far less important than their luck and opportunism. At some point in 2012 or 2013, they chose to make common cause with their old enemy Saleh, who was furious about his ouster and looking for allies to help him seek revenge. Lackner describes this partnership as “perfidious,” and it’s hard to disagree. Saleh represented everything the Houthis stood against, and they had suffered terribly at his hands during the wars that lasted from 2004 to 2010. They made the deal because Saleh gave them what they needed to conquer Yemen: vast stores of cash (bilked from Yemen’s oil revenues) and powerful cadres of the Yemeni military that were still loyal to him. Lackner, who finished her book in 2017, predicted that a breakup of the Houthi–Saleh alliance would weaken both parties and lead to a quick victory by the Saudis. She was wrong. The breakup came at the end of 2017, when Saleh quarreled with the Houthis and tried to outmaneuver them. The Houthis killed him and remained as strong as ever.

The Houthis have also benefited—militarily at least—from their alliance with Iran and Hezbollah, which have provided essential training on infantry tactics, anti-tank fighting, mine-laying, and anti-ship attacks in the Red Sea. Iran has provided ballistic missiles that the Houthis have fired across the border into Saudi Arabia in strikes that would have been devastating if the Saudis did not have American-supplied defense systems. The Iranian connection, of course, is also the reason the Saudis and their allies have laid waste to Yemen for the past four years. They consider the Houthis an Iranian dagger aimed at their heart. The war has not helped them remove the threat. But unless some way can be found to assuage Saudi Arabia’s fears of Iran, the fighting is not likely to end.

As I was driving across the Yemeni highlands in September, there was a surreal sight: a group of five Africans, possibly Somalis, walking northward on the roadside. They were bare-headed in the fierce midday sun and carried almost nothing, apart from a few plastic bags. They had probably crossed the Red Sea by boat from Africa, a common refugee route, and were now walking hundreds of miles, through an active war zone, in hopes of slipping illegally across the Saudi border and finding ill-paid construction jobs. These kinds of migrants were a common sight before the war; hundreds of them died at sea, victims of brutal smugglers or shipwreck. Those who survived faced a punishing journey across the desert and the near certainty of being turned back by Saudi border guards.

I was surprised to see the Africans because for several years now, people have been crossing the other way. After the bombs began falling in 2015, several thousand Yemenis fled across the water to Somalia, and in the following year, Djibouti accepted 20,000 Yemeni refugees, most of them no doubt hoping to make it up to the Mediterranean and across to Europe. As with their Somali counterparts, many of these migrants died at sea. The African group I saw in September was proof that Yemen—for all its legendary remoteness—is also a global crossroads, a hell for some people and a refuge for others.

It is an ancient pattern. Trauma and exodus have shaped Yemen’s culture for centuries, with waves of migrants leaving their stamp on far-flung cultures and often returning to hybridize their own. Traders from the southern coastal region of Hadramawt began traveling to Southeast Asia in the 1600s and played an important part in spreading Sufi Islam there. I know Yemeni families who can trace their ancestors’ odysseys to medieval Spain, then to the Levant, and back to Yemen again. Some of them never broke their ties: long before the advent of Moneygram, Hadrami traders scattered across Asia were sending their earnings back to Yemen. Some of them went home and built grand houses in a style that became known in Yemen as “Javanese baroque.” I saw some of these mansions, abandoned and ghostly, in the Hadrami city of Tarim years ago; their owners fled in 1970 when the Marxists took over South Yemen.

Some exiles never returned. After deadly attacks on Jews around the time of Israel’s creation, the British and American governments helped transfer some 49,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel, in what was dubbed “Operation Magic Carpet.” Decades later, traders in the old city of Sanaa will still show you beautifully wrought silver jewelry and say with pride that it was made by Yemeni Jews, who were renowned for their craftsmanship.

It is tempting to take some comfort in Yemen’s survival through the repeated traumas of its past, which suggests that it will survive the present crisis too. But this one may be different. Yemen’s water crisis is unprecedented. The country is almost totally dependent on subsurface aquifers whose rapid depletion has been accelerated by subsidies for well-drilling. The solution, as Lackner writes, has long been obvious: Yemen must stop using 90 percent of its water for agriculture and start prioritizing people and livestock. That was never done during the long rule of Saleh, who was politically beholden to large rural landlords. To do it now would require a reordering of Yemen’s economic priorities, which seems almost impossible in the country’s present state of fragmentation. But ignoring it, Lackner writes, presents “an existential threat” for Yemen.

The lesson of the loss of the great dam of Marib, which marked Yemen so deeply more than 1,400 years ago, seems more relevant than ever. The need for a reliable source of water may be as great as the need for peace. Yet this, too, may be forgotten. In 2015 airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition hit the remains of the dam’s sluices, sending the old stones toppling to the ground.

—January 23, 2019