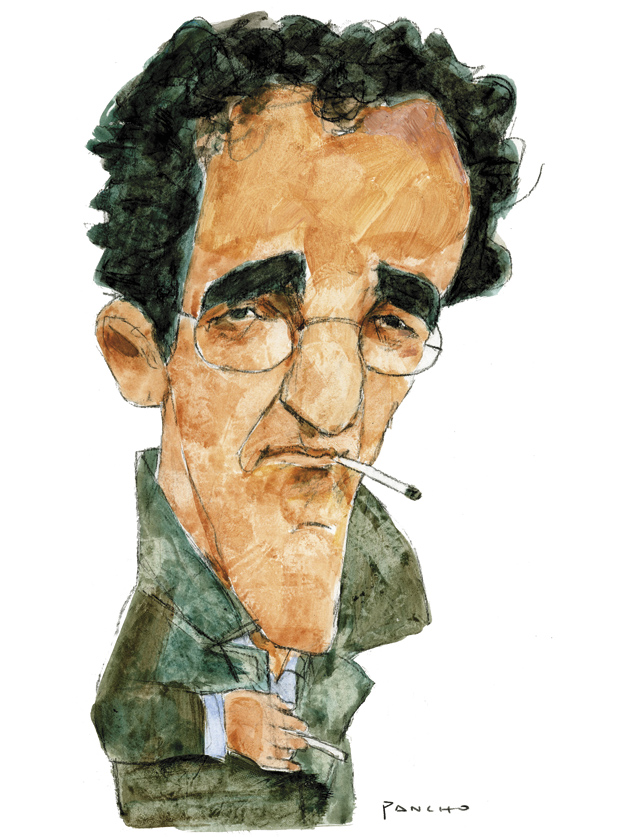

“I abandon books easily,” the Chilean novelist, story writer, poet, and essayist Alejandro Zambra said in a 2015 interview with the Peruvian novelist Daniel Alarcón.

Before, especially when I wrote literary criticism, I had the urge to read books from cover to cover. If I was writing about them, I’d read them twice over. I didn’t enjoy that, in part due to the obligation to say something beyond the obvious. I don’t do that anymore; I became more impulsive—there are just too many books I want to read.

The specter of “obligatory readings” haunts Not to Read, Zambra’s collection of reviews, essays, and lectures; it’s also the title of the first essay in the book, about an early, unhappy encounter with Madame Bovary in middle school at the prestigious National Institute of Chile. “I feel sure that those teachers didn’t want to inspire enthusiasm for books, but rather to deter us from them, to put us off books forever,” he writes. “They didn’t waste their spit extolling the joys of reading, perhaps because they had lost that joy or had never really felt it.”

It is much to the benefit of his fellow readers, then, that through whatever alchemy turns oppressed students into book-mad adults and put-upon book reviewers into compulsively engaging literary evangelists (would that it happened more often!), Zambra has emerged as one of the most perceptive and generous writers on literature currently at work. Most poets and fiction writers are, presumably, obsessed with books. It is rare, however, to find one who is able to articulate that obsession with as little pretense and as much élan as Zambra. He puts down on paper the conversations and internal debates that readers and writers usually have off the page—the number and type of books one takes on a long journey, the judgments one makes about acquaintances upon seeing their bookshelves for the first time, the marginalia found in an old book that seem to uncannily echo or refute one’s own internal reactions. These are the things that make up a bookish life, and in his essays and reviews Zambra captures them with a combination of (seemingly) offhand casualness and authority.

Not to Read is Zambra’s first book that presents itself, at least superficially, as a traditional work of nonfiction, but all his books—from his debut novel-in-miniature Bonsai (which narrates many years in the lives of a couple, together and apart, in less than ninety pages) to his most recent work, Multiple Choice (which takes the form of Chile’s secondary school placement exam in 1993, the year that Zambra took it)—rather freely disregard the distinctions between genres. His short-story collection, My Documents, perhaps the clearest and most expansive delineation of his concerns as a writer, toggles between pieces that read like memoir (an essayistic narrative about quitting smoking, dedicated to his peers in cross-genre experimentation Valeria Luiselli and her husband, Álvaro Enrigue) and stories that, in the clear-eyed third-person ruthlessness with which they depict their usually Zambresque protagonists, stand behind the veil of fiction.

Even in Not to Read, in what seems to be the recognizable, if flexible, form of the essay, uncertainties creep in. The essay about reading Madame Bovary as a schoolboy appears nearly verbatim in the thoughts of the narrator of Zambra’s third novel, Ways of Going Home. “Free Topic,” which began as a lecture delivered at Diego Portales University, includes the full text of a short story, “a text I worked on for months and then decided not to publish, but whose existence I find in some way as undeniable as it is problematic.”

Like that of the best practitioner-critics, Zambra’s writing about literature makes the case for a personal canon that, unsurprisingly, has a perfectly Zambra-shaped space available for his body of work. The subjects of Zambra’s essays lean heavily toward Latin American and Italian writers, many off the radars of American readers, and he has a particular affection for works that, like his own, give the appearance of the minor or the merely personal but, in fact, contain entire worlds.

The English-language edition of the book (it has shape-shifted slightly each time it has been published in another country) is divided into three sections. The first consists mostly of shorter pieces written for newspapers, alternating between pithy personal essays about the writing and reading life and quick takes on books and authors. The second section is made up of longer considerations of writers who have been important to Zambra, including the Chilean (anti-)poet Nicanor Parra, the Peruvian story writer Julio Ramón Ribeyro, and the midcentury Italians Cesare Pavese and Natalia Ginzburg. The heart of the third section is made up of a series of speeches and lectures in which Zambra explores at greater length some of his central ideas as a critic: the tension between “required” reading and that which is undertaken freely, the ways one’s idiosyncratic methods of reading and writing shape one’s perception of the world, and the value of writers who are willing to display the strangeness of their particular obsessions.

Advertisement

Politics are not the priority in these pieces, with the exception of a scabrous 2012 column that, after listing the many failings of the government at the time, concludes that it is “an immense relief not to have to review that devastating and badly written novel that Chile has been for so many years.” Zambra frequently invokes his identity as a Chilean writer, however, with his characteristic blend of pride and self-deprecation. There is a sense—for example in his piece on the poet and reporter Robert Merino’s articles about Santiago, or in his narration of a visit to the elderly Parra—that he is attempting to create a more nuanced, alternative portrait of a country that has been defined for so long by dictatorship and its aftermath.

Zambra was born in 1975, two years after the right-wing general Augusto Pinochet overthrew the democratically elected socialist government of President Salvador Allende, initiating the violent and repressive dictatorship that lasted until he was voted out of office in 1990 following a plebiscite that restored democracy to the country. (As Zambra notes in the interview with Alarcón, though, Pinochet’s psychological hold was such that his true reign over the country did not begin to come to an end until his 1998 arrest in London for human rights crimes, and did not really end until his death in 2006.)

He was raised in Maipú, a suburb of Santiago that serves as the setting of Ways of Going Home. Perhaps as a result of his having grown up on the edge of the city, his writing about Santiago retains some hope in the possibilities of the metropolis, even at its bleakest. “When I was eleven years old and started to travel to school every day (I lived on the city’s outskirts, an hour and a half from downtown) I fell in love with that landscape: dirty, interesting, crowded, dangerous, impersonal, chaotic,” he writes in “The City Will Follow You,” the essay about Merino.

A place where everything was happening, where no one belonged. I started class at two in the afternoon, but I left my house very early so I could wander through those new streets, whose names I only knew because they appeared in the local version of Monopoly.

Though all of Zambra’s novels engage directly or indirectly with the ghost of Pinochet, Ways of Going Home is his most explicit attempt to grapple with the human costs of the dictatorship. In the novel, the young narrator befriends a girl in his neighborhood named Claudia and agrees to her request to spy on her uncle Raúl, who lives next door to the narrator’s family, and report back to her on his activities. He dutifully does so, collecting information that he doesn’t understand, before he is abruptly told that his services aren’t needed anymore. Years later, he learns the truth: Raúl was in fact Claudia’s father, Roberto, forced to live separately from the family for their protection because of his participation in leftist politics. The narrator, as an adult, brings this news to his apolitical, quietist parents. “It’s a complicated story, but a good one,” his father says. The narrator is furious at his father’s callousness, but his father holds firm: it’s a good story because, despite the years together that the family lost, no one died for political reasons.

Zambra has written and spoken repeatedly about the sense of belatedness that his literary generation has had to confront. “We took refuge in the idea that history had happened to our parents,” he said in the interview with Alarcón (whose novel Lost City Radio Zambra writes about admiringly in Not to Read). “We’re a shielded generation but, at the same time, a brave one. We weren’t the ones having to tell a story, but the ones having to listen to it. We had this generalized sensation of being secondary characters.” As a result, he writes in a review of a book by Pilar Donoso, daughter of the famed “Boom” writer José Donoso, “it took us too long to understand that we also had our own stories.”

Those stories, in Zambra’s hands, are often ones of minor failure or stagnation, of characters who attempt to assess the trajectory of their lives while mostly staying still. His first novel, Bonsai, is a feat of seduction, drawing the reader effortlessly into the relationship of two ordinary Chileans, Julio and Emilia, the latter of whom, we are told in the novel’s first sentence, will die by the end of the book. In a series of vignettes, the reader gets glimpses into the couple’s burgeoning infatuation, most memorably through their shared reading material. Early in their relationship, they lie to each other about having read Proust, requiring them to “reread” it together later on.

Advertisement

But they are genuinely, adorably turned on by literature. “On a particularly joyful night,” Zambra writes,

Julio read, in a joking tone, a Rubén Darío poem that Emilia dramatized and turned banal until it became a genuinely sexual poem, a poem of explicit sex, with screams, with orgasms included. It became a habit, this reading aloud—in a low voice—every night, before shagging. They read Marcel Schwob’s Monelle’s Book, and Yukio Mishima’s The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, which turned out to be reasonable sources of erotic inspiration.

With the impertinence (and none of the usual uncertainty) of the first-time novelist, Zambra skips past the presumably typical souring of the relationship to episodes from their lives after its demise: Emilia suffers through a terrible night out with a friend’s husband; Julio tries to get a job typing up a self-important novelist’s handwritten manuscript, but ends up improvising his own novel instead. “They both knew that, as they say, the end was already written,” he writes, “the end of them, of the sad young people who read novels together, who wake up with books lost between the blankets, who smoke a lot of marijuana and listen to songs that are not the same ones they separately prefer.” The reader can’t help but laugh at himself for hoping otherwise.

His brief, devastating second novel, The Private Lives of Trees, takes place over the course of a night in which the professor protagonist, Julián (whose published novel sounds a lot like Bonsai), tells a bedtime story to his step-daughter Daniela while waiting for her mother Verónica to return home from an art class. As the night wears on without Verónica’s arrival, Julián becomes convinced that something terrible has happened. He imagines her, in great detail, with another man, but dismisses that awful but still relatively benign possibility:

Not even by fanning the flames of his horrible imagination can Julián change the plot: he is sure this is not the reason for his wife’s lateness. The image of Verónica lost on a distant avenue becomes huge, turns into a kind of truth…. To get out of this would mean Verónica crossing, as though nothing had happened, a threshold that has been closed for hours. To get out of this would mean, perhaps, waking up. But he can’t wake up: he is awake.

Here the worst possible horror is uncertainty, and the reader feels Julián’s grim need to carry on in the face of it. Will it be, in the end, “a good story”? It does not seem likely. While the fear shadowing Julián is not explicitly political—we are in the tentative, post-Pinochet era—it echoes the fear of the country that Zambra was born into: the possibility of disappearing without a trace, directly or indirectly by the hand of the state.

Reading Not to Read alongside Zambra’s fiction is like being given a blueprint to the author’s technique, though one in which all of the rooms have been reordered and transposed to a different neighborhood. As a reviewer, Zambra is an enthusiast par excellence—one reads his pieces with a search engine window open, hoping that these tantalizing titles will be available in English. Some of his most adventurous-sounding subjects—the stories of Hebe Uhart and Alejandra Costamagna, the playful memory books of Sandra Petrignani, the metafictions of Josefina Vicens, the uncategorizable diaristic works of Mario Levrero and Alejandro Rossi—have either not been published in English or have fallen out of print, rendering Zambra’s descriptions of their contents and authors valuable feats of imagination in their own right, especially for those of us with insufficient Spanish. (Happily, Coffee House Press will be publishing an English translation of Levrero’s Empty Words, a playful chronicle of the author’s attempts to improve his handwriting, in May 2019, and a selection of Uhart’s stories will be published by Archipelago Books in the fall.)

In Zambra’s universe, as in that of his always-looming and much lionized predecessor Roberto Bolaño, literature can transmit power in spite of, and even as a result of, its existence as nothing more than rumor. Scarcity and, in Pinochet’s Chile, censorship can breed invention. Zambra writes nostalgically of his collection of books that he owns only as photocopies, though by the time he was engaged in this clandestine copying it was due to the high cost of books in Chile rather than political necessity. Zambra recalls how the act of copying made these editions wholly distinctive, bestowing on the works of literature the personal touches of their assemblers. “I remember a classmate who photocopied War and Peace at a rate of thirty pages per week, and a friend who bought reams of light blue paper because, according to her, the printing came out better,” he writes.

The greatest bibliographic gem I have is a slipshod but lovingly made copy of La Nueva Novela [The New Novel], the inimitable book-object by Juan Luis Martínez that we tried to imitate anyway. My version is complete with a transparent inset, a Chilean flag insert, a page with Chinese characters intermingled in the text, and fishhooks stuck to the paper.

It is hard to imagine a better synecdoche for Zambra’s ideal vision of what a book should be: heterogeneous, unique, and at least a little bit dangerous. (It’s also hard to imagine what the book he describes actually looks like or how, if at all, one reads it, but that does not decrease its allure.)

In Not to Read’s longer pieces, he circles his subjects keenly, noticing details and finding new angles from which to approach the work. His essay on Bolaño takes a discursive, fragmentary form, echoing the elder writer’s preferred structural approach, making connections via juxtaposition rather than explicit argument. “Bolaño’s poems are the poems Bolaño’s character’s wrote: the unintelligible novelist brings the unintelligible poet to the fore,” he writes in one of the sections, attempting to pin down the elusive nature of his verse. Then, later in the essay, he restlessly flips that observation:

Perhaps Bolaño’s characters would not have written the novels that Bolaño wrote: they would have needed a lot of glue, and above all, resignation…. Archimboldi [the mysterious central figure of Bolaño’s novel 2666] is a hero, but he is not a poet: he thinks that all poetry can fit into a novel, that only a novel can communicate what poetry is. Bolaño’s work tells the story of a poet resigned to being a novelist. A poet who descends to prose in order to write poetry.

It is worth noting here that Zambra, like Bolaño, began his writing life as a poet but, also like him, found far greater success as a fiction writer. In his gloss on the paradoxes of Bolaño’s most successful work—fictions that glorify poetry for a wider audience but inevitably, even in Bolaño’s adventurous prose, tame it—Zambra speaks to the dilemma of the avant-garde writer torn between innovation and communication.

The work he treasures most, at least in his passionate redescription, often exists in this dynamic space between forms, both democratic and formally or philosophically challenging. In his essay about the revolutionary gay writer Pedro Lemebel, much of whose important work was originally presented in public manifestos, newspaper crónicas, or over the radio, Zambra writes that to give him Chile’s National Literature Prize “would be to reward that whole horde of readers who more or less by chance came across some texts that were provocative, strange, very Chilean, cantankerous, bitter, funny, sentimental, sharp, elegant, entirely legible and at the same time complex.” Despite this paean to Lemebel’s “horde of readers,” Zambra can’t resist a riff at the expense of the very popular Isabel Allende, noting that since she once received the prize, it might not in fact be worthy of Lemebel. (For the most part, when Zambra determines that a book or an author is unworthy, his critique is usually humorous, and the target is, by definition, a writer with an unjustifiably inflated ego or reputation. The most amusing of his infrequent hit jobs is a faux-naive review of a volume “by the eighty-something Polish author Karol Wojtyla,” better known as Pope John Paul II, which makes note of his habit of “writing certain words with capital letters, for no apparent reason.”)

In “Searching for Pavese,” one of the few instances in which one sees the author undertaking something resembling a conventional journalistic assignment, Zambra uses the occasion of a trip to the town of Pavese’s birth to reconsider his relationship to the author’s body of work. Like Geoff Dyer (a spiritual peer) on the trail of D.H. Lawrence in Out of Sheer Rage, Zambra feels his enthusiasm for Pavese wax and wane as he confronts the clichés of the literary tourist trail. “I’m sure that foreigners come to Santo Stefano, like me, just to see Pavese’s birthplace, which turns out to be a fairly uninspiring house,” he writes. “‘The poet was born in this bed,’ the guide tells me, and there’s nothing for it but to imagine little Cesare crying like the damned.”

He contemplates the reasons for his increasingly dim view of Pavese’s diaries, published as This Business of Living, which he had greatly admired in his youth. His ambivalence is all too recognizable to anyone who has returned to a formerly beloved writer and found him or her wanting. A friend suggests glibly that perhaps Zambra related to Pavese when he was young because he too wanted to commit suicide. But no, Zambra thinks, “with Pavesian seriousness,” that’s not it. “Maybe back then, at twenty, I was impressed with his way of expressing turmoil, his precise description of a suffering that seemed enormous and that, even so, couldn’t compete with the possibility of depicting it,” he writes.

He admires Pavese’s language, his refusal to accept commonplace methods of expression:

But in another sense he is a poor guy longing to put his small wounds on display…. I wonder if it truly mattered to anyone to know about his impotence, his premature ejaculations and his masturbations. I don’t think so.

But then he returns to The Moon and the Bonfires and finds much to appreciate all over again. The drama of Zambra’s wavering is contagious: one finishes the essay eager to reread Pavese, even if one hasn’t yet read him in the first place, in order to compare notes.

Zambra’s highest praise is reserved for Pavese’s friend Natalia Ginzburg, whose blend of the domestic and experimental serves as a clear antecedent to his own quiet explorations. He sees in her work the close examination of the quotidian that he admires most. He commends

her refusal to look for the new places far removed from the very nature of experience. She knew that it was impossible not to be original. That any family, any person looked at from up close reveals their singular condition. Or doesn’t reveal it, but also doesn’t deny it: they show their opacity, their impossible recesses, the evidence of their secret.

To reveal the “singular condition” of a character or work of art is perhaps the ultimate goal of the humanist writer, and Zambra, in both his fiction and his criticism, succeeds in doing so with remarkable consistency. One feels, finishing this book, about Zambra and Spanish what he feels about Ginzburg and Italian. “On top of my wish to have read Natalia Ginzburg sooner, I also want to know Italian,” he writes. “Not to learn it, but to know it now, all of a sudden. It’s not so easy.”