The story of twentieth-century art is crowded with chastened and disabused idealists. How could it be otherwise? Each of the great movements—Fauvism, Cubism, Constructivism, Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism—began with its own kind of evangelical fervor. These artists were rejecting quotidian experience as they pursued emotional states so unfamiliar or so overpowering as to call into question the fundamentally empirical and materialistic nature of a work of art. Painters and sculptors were raising hopes for artistic catharsis that no painting or sculpture, not even a masterpiece, could ever be expected to fulfill.

Sooner or later, the long, hard hours in the studio had a way of turning even cockeyed optimists into pragmatists. The spirit was rarely any match for the exigencies of clay, metal, stone, or oil paint. Picasso, at least for a time, renounced Cubism’s shape-shifting kaleidoscope in favor of the braggadocio of Neoclassicism. Mondrian, after the Olympian austerities of paintings with the tiniest handful of black lines and shapes, embraced the boogie-woogie rhythms of New York City. Hope wasn’t so much abandoned as transformed. Pessimism provoked new forms of optimism. If Duchamp turned disabused idealism into a radical skepticism, there was Donald Judd to come along and insist, despite all the evidence to the contrary, that you could still hope against hope. With the one hundred mill aluminum boxes that Judd arranged in two buildings in Marfa, Texas, in the 1980s, he reimagined an ancient perfection amid the parched landscape of the American Southwest. Judd’s industrial-strength idealism revived some very old dreams.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the abstract artist who died in 1943 at the age of fifty-three, was the most exquisitely chastened of all the idealists of her generation. Abstract art was in its infancy in the years around World War I when she was a young woman and became involved in avant-garde circles in Switzerland and Germany. She witnessed firsthand the arguments and struggles that attended the search for a new reality—one beyond everyday reality—that preoccupied Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian. Her career began gradually, with experiments in the decorative arts, involvement with the modern dance movement, and participation in some of the earliest exploits of the Dadaists. The ascetic paintings she produced in the last decade of her life—with their forceful rhythmic arrangements of circles, semicircles, and rectangles and their unequivocal orchestrations of color—are rigorous without being the least bit doctrinaire. Her finest work has the clean-lined beauty we associate with the art of Malevich and Mondrian, except that where they saw infinities and eternities she saw particularities and immediacies.

Roswitha Mair describes Sophie Taeuber-Arp and the Avant-Garde, which was first published in Germany in 2013, as a “sketch.” The writing, in a highly readable translation by Damion Searls, is lucid and direct. The entire story, presented in just under two hundred pages, has an easy, agile pace. For readers who are unfamiliar with all the ideological crosscurrents that engaged artists and critics in the early decades of the twentieth century, Mair’s glancing discussions of Russian Constructivism, the De Stijl Movement in Holland, and any number of other matters may feel a little thin. But her rather casual approach to the tangled ideological arguments of those times has its advantages.

Studies of the early years of modernism are all too often sunk by a scholar’s feverish efforts to impart some ultimate clarity to polemics and arguments that by their very nature were emotional, impressionistic, and often downright incoherent. There can be a danger in putting the writings of the painter Theo van Doesburg or the poet André Breton under the microscope. Many of their contemporaries took even their most trenchant arguments with more than a grain of salt. For every argument there was a counterargument. And the battle lines were constantly shifting. Mair’s aversion to polemical intrigue feels appropriate for an account of the life of Taeuber-Arp, who seems to have always known who she was and what she was after.

By the end of her relatively short life—she died in her sleep, asphyxiated by a faulty stove—Taeuber-Arp was a figure to be reckoned with in the exhibitions and journals where several generations of abstract artists were making their case to the still very small audience that took an interest in such work. Because her achievement has never become especially well known, there may be a temptation to argue that the fact of her being a woman has stood in the way of wider recognition. While there is some truth to this, there are other factors to consider. She embraced a kind of abstraction, chaste and at times almost inscrutable, that rarely attracts more than a few fervent admirers—the same kind of small, ardent audience has embraced the work of the American painter Myron Stout.

Advertisement

As for many of Taeuber-Arp’s other activities—her experiments with marionettes and her interior designs—it’s difficult for even the most accomplished historian to reconstruct their full import. When we consider that Taeuber-Arp died before the audience for abstract art exploded in the postwar years, I think it is fair to say that her impact has been far from negligible. After the war, her work was widely exhibited in Europe. The young American painter Ellsworth Kelly was among a new generation that was deeply impressed by her achievement. In 1981 she was the subject of a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Taeuber-Arp’s art and life are impossible to reconcile with our celebrity-obsessed age. She expressed herself through a language of pure form that she knew from the beginning wasn’t going to earn her instant or easy popularity. She was aware that the fight for acceptance was difficult if not perilous. Then she watched the Nazi rise to power and the extinction, all across Europe, of so many of the schools, galleries, museums, and publications that had only begun to celebrate the avant-garde innovations to which she dedicated her life. And yet among those who are passionate about pure abstract art, her importance has rarely been in doubt.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp was born in Davos Platz, Switzerland, in 1889. She was the youngest of five children, one of whom had died of meningitis as an infant. The family was cultivated and sophisticated, and buffeted by tragedy. Her father, who suffered from tuberculosis, died two years after Sophie’s birth. Her mother, who saw to it that her children had a secure middle-class upbringing despite some financial uncertainties, was felled by cancer when Sophie was still in her teens. Throughout her life, Sophie remained close to a sister, Erika, and a brother, Hans. By the time their mother died, Hans was at the beginning of a very distinguished career as an antiquarian book dealer.

There never seems to have been any doubt that Sophie would have some sort of career; feminism couldn’t be ignored (at least not entirely) in the comfortable, educated middle-class milieu in which she came of age. Her mother was a creative spirit who was involved with the decorative arts, painted in oils, and designed a house for the family. During her studies in her teens and early twenties in Trogen and then in Munich, Taeuber-Arp was swept up in a revolution in the arts that had begun with John Ruskin and William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement in nineteenth-century Britain.

The Arts and Crafts Movement rejected the machine-made objects that were becoming ubiquitous in Europe and the classical figures that had shaped the curriculum of European art academies since the eighteenth century. The new ideal was the artisan of the Middle Ages, for whom the creation of a banner, an altarpiece, a suit of armor, and a stained-glass window were all part of the same glorious creative endeavor. For Taeuber-Arp, who as a woman of her time initially found herself studying embroidery, weaving, and the principles of design, the message of the Arts and Crafts Movement was that what had once been dismissed as secondary disciplines were now absolutely primary. In the avant-garde circles she seems to have nearly effortlessly joined, an education in the principles of design prepared an artist to create just about anything: a blanket, a painting, a building.

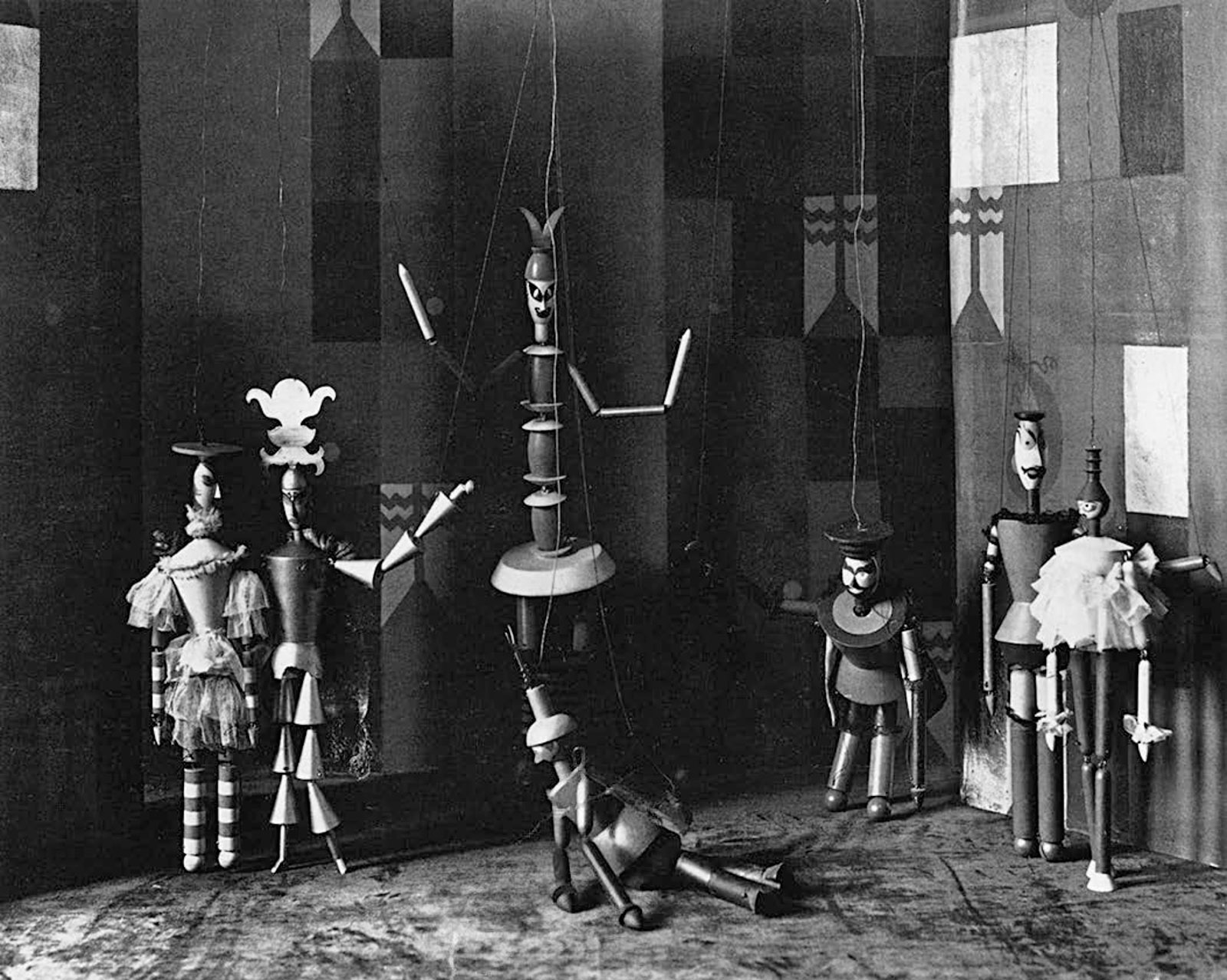

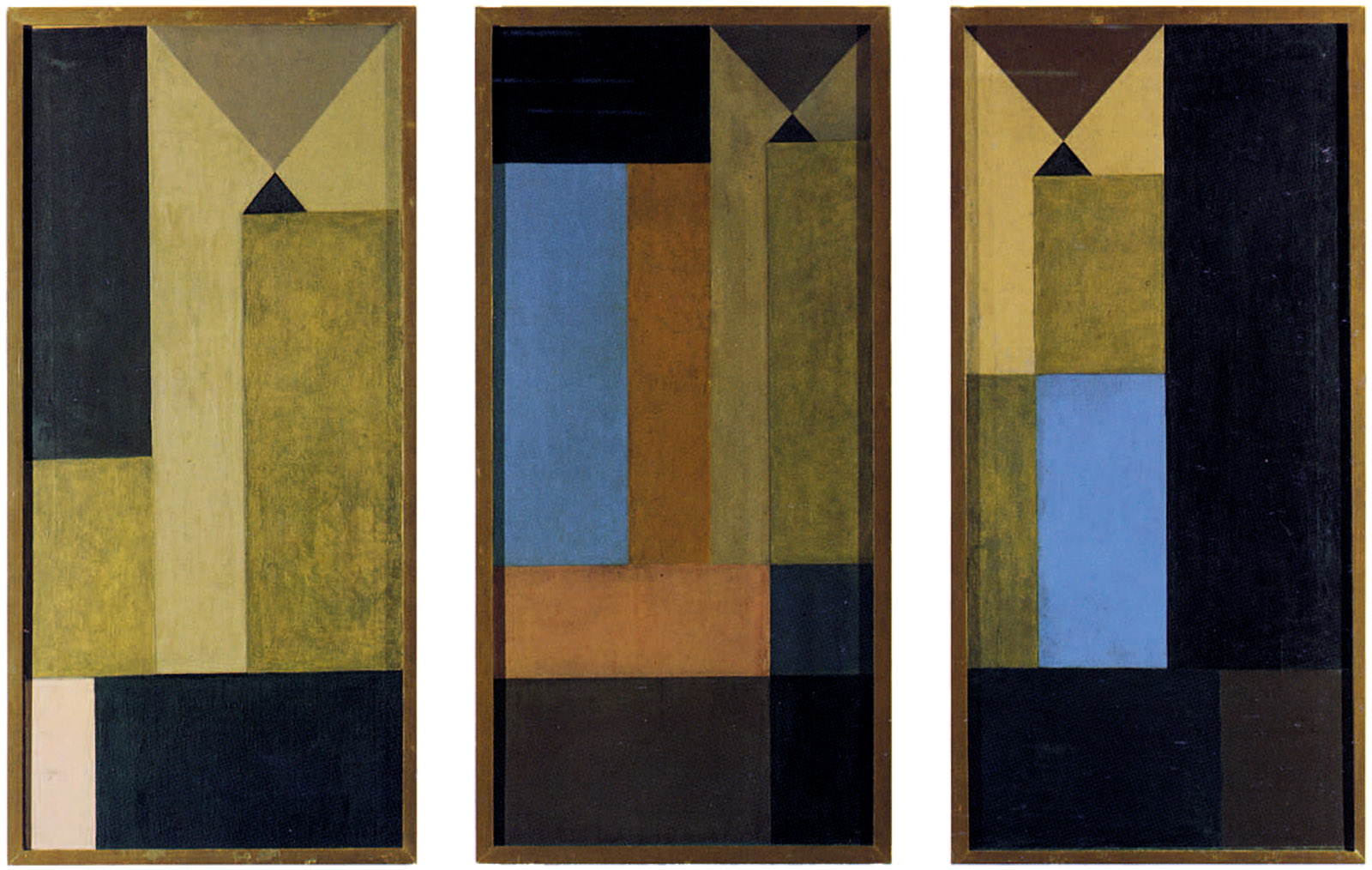

Taeuber-Arp never felt any compunction about moving, almost simultaneously, in a number of different creative directions. Whatever she did in her twenties and early thirties reaffirmed and reinforced a sensibility that was at once steely, stalwart, and playful. For a time she participated in the modern dance movement; she worked with Rudolph Laban and knew Mary Wigman and was said by some to be a striking dancer in her own right. There are beguiling photographs of her in an exotic costume that she designed for herself in 1914 or thereabouts. Just shy of thirty, she created for a theatrical production called King Stag a collection of elongated, brilliantly colored marionettes, with bodies composed of cones, spheres, lozenges, and cylinders that add up to a modern twist on a rococo fantasy. They have long had a secure place in the history of theatrical experimentation. At the same time she produced a first group of abstract paintings, compositions of rectangular forms realized in opulent colors and sometimes accented with areas of gold, as if to suggest a contemporary secular version of an early Renaissance altarpiece. These stirring inventions have a somber, processional power; they are among the signal achievements of the first decade of abstract painting in Europe.

Advertisement

Taeuber-Arp was young and ambitious—but then youth and ambition were the order of the day. While the horrors of World War I and its aftermath made the optimism of the first years of the century difficult to sustain, she belonged to a generation that when forced to give up the old faith in perpetual progress embraced the loss of faith as if it were a new faith. The chaotic spirit of the times found an outlet in the celebration of the irrational and outrageous embraced by the Dadaists, who were determined to thumb their noses at anything and everything and see what happened next. The movement has come to be identified with the idea of anti-art—an art, in other words, that confounded all the conventions of form, structure, and meaning traditionally associated with painting and sculpture. But Dadaism was also wildly heterogeneous. As the movement spread from Zurich to Berlin, Hanover, Cologne, New York, and Paris it was constantly changing, with Dadaists sometimes embracing elements of social or political critique and at other times arguing for what amounted to a more hard-edged and cynical version of the old art-for-art’s-sake.

Taeuber-Arp was part of the first wave of Dadaist exhibitions and events in Zurich. She found friends and collaborators in Hugo Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck, Hans Richter, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Arp, whom she quickly became close to and married in 1922, seven years after their initial encounter. From their alliance were born all the confusions about her name. She was sometimes Taeuber, sometimes Taeuber-Arp, and sometimes Arp-Taeuber. But she wasn’t the only one with multiple appellations. Arp, who was born in Strasbourg, was sometimes Jean Pierre Guillaume Arp and sometimes Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp. To this day he is almost interchangeably referred to as either Jean or Hans.

Arp was a brilliant sculptor and a master of the art of collage—and a charmer, a dandy, and a narcissist. People liked him that way. They expected him to take up a lot of oxygen in a room. He exulted in his inability to manage the ordinary business of life and came to take it for granted that Taeuber-Arp would not only cook and keep his clothes in order but also earn a living for the two of them, which she did for many years by teaching. If she sometimes seemed to subsume her will in his—when they first met she executed embroidered panels based on his designs—she never really let him limit what for the quarter-century they were together were her own expanding horizons.

There wasn’t much of anything that Taeuber-Arp didn’t believe she could do. She took up interior design as a way to make some money and was involved, along with Arp and Van Doesburg, in the design of the Aubette in Strasbourg. With its dramatically simplified murals and stained-glass windows, the building is now recognized as one of the most radical architectural inventions of the second quarter of the century. When she and Arp finally had the wherewithal to build a house in Meudon, in the suburbs of Paris, she designed the modernist structure herself, with one floor for her and one floor for Arp, and installed next to it a cubist garden that deserves a place in the history of landscape design. In the late 1930s she founded and pretty much single-handedly edited an art magazine entitled Plastique.

For students of modernism, who feel most comfortable when they can label an artist as a Dadaist or a Surrealist or a Constructivist, both Taeuber-Arp and Arp pose serious challenges. True, they helped ignite the powder keg that was Dadaism in Zurich during World War I. But they also cultivated a lucidity that aligned them with a new classicism and even perhaps a new Platonism that was embraced by Mondrian, the De Stijl movement, and others across the continent. They weren’t the only ones who cultivated what some might regard as a paradoxical union of irreconcilable forces. Van Doesburg, at one point among Mondrian’s closest allies, had a double life as a Dadaist; he was sometimes known by a second name, I. K. Bonset. As for Kurt Schwitters, the collages he made from the utterly anticlassical flotsam and jetsam of everyday life were organized in compositions with a rectilinear rigor.

The careers of both Taeuber-Arp and Arp ought to give pause to the critics and historians who insist on always equating Dadaism with anti-art. In the anything-goes art world that we live in today—where Maurizio Cattelan, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons have broken auction records with their Gilded Age repackagings of Duchamp’s sardonic asides—it is all too easy to regard Dadaism as a wrecking ball and not much else. Certainly demolition is what many people believe that Duchamp, now generally regarded as the king of the Dadaists, was up to when he drew a mustache on the Mona Lisa. But whether Duchamp was a nihilist—and, if so, what kind of nihilist—is a question to which the artist himself clearly preferred that there be no conclusive answer.

As for Taeuber-Arp and Arp, they apparently saw Dadaism as raising questions about the nature of art to which there had to be answers. When they traveled in Italy they were enthusiastic students of the art of the Renaissance. They might have wanted to blow things up, but that didn’t prevent them from seeing the past as prologue. They believed that once you rejected the old reality you were obliged to discover a new one. For both of them that meant a preternatural clarity in the way forms were realized. For Taeuber-Arp those forms were almost invariably strictly geometric. For Arp they were elementally biomorphic. On the shifting sands of nihilism they constructed a new classicism.

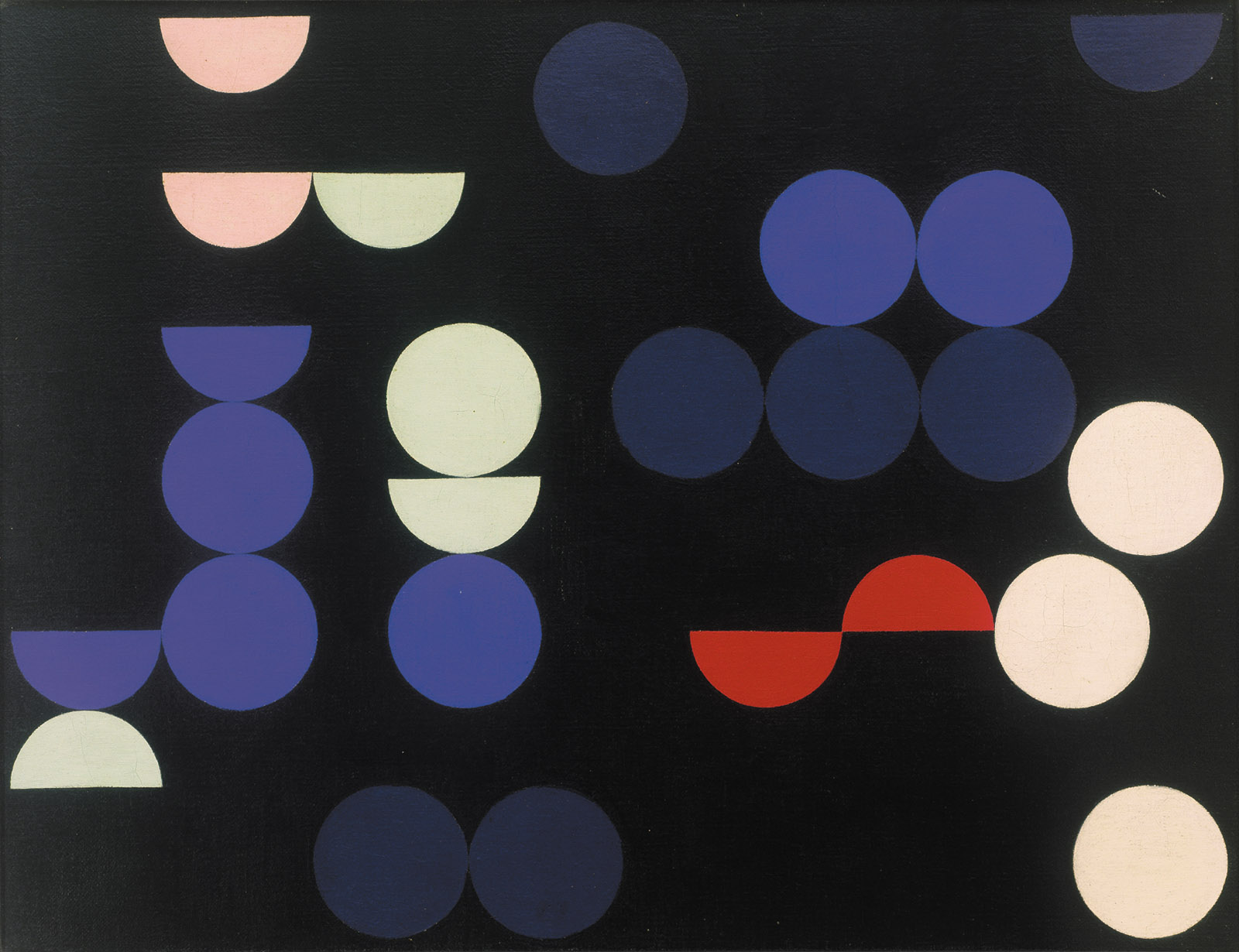

Taeuber-Arp’s finest works have a plainspoken eloquence. Although she first took up a brush when she was a young woman, my sense is that she only fully embraced the art of painting in the 1930s, after her base of operation shifted to France, where Poussin’s classicism had held sway since the seventeenth century. Among the most thoroughly original of her paintings are gatherings of circles, semicircles, and circular segments, sometimes interrupted by rectilinear forms. Taeuber-Arp’s tight-knit compositions have a rhythmic purity and dignity unlike anything else in twentieth-century art. They are flatness incarnate—a flatness so insistent that it seems capable of containing all space and all time. Both her forms and the space or non-space or anti-space that surrounds her forms are rendered opaquely, in white and a few basic colors.

Some have seen in the orderly marshaling of her forces an allusion to the dance notation that she would have known from her days working with Laban and Wigman. There is something dance-like about Taeuber-Arp’s abstractions. They are slow, deliberate dances. They suggest not theatrical virtuosity but the stripped-down beauty of an athlete doing the most basic exercises. Taeuber-Arp’s circles, semicircles, and rectangles are the bones and muscles of a new visual art.

She kept trying different things. She experimented with the third dimension, arranging rows of small circular pieces of wood to create polychrome reliefs. She mingled her circles with black lines to create fantastical plant forms. She sometimes permitted her circles to turn into sensuous curves, which she picked off one by one so as to isolate their pristine beauty. For a number of works she developed a shape like a hat, with a flat bottom and a slightly peaked top, and repeated it seven or eight times in a series of echoing forms, each one slightly different, like a musical phrase repeated by different instruments or different voices. Her immaculate craft was a rebuke to the chaotic times she was forced to endure.

While at least for a time Arp’s irrepressible self-regard kept him somewhat insulated from the gathering horrors in Germany and beyond, Taeuber-Arp could not look away. Adolf Ziegler, a man for whom she had had romantic feelings when she was a young woman, became a major figure in Hitler’s assault on modern art and organized the notorious “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich in 1937. She was deeply upset when her brother saw in the Nazi liquidation of Jewish businesses a golden opportunity and purchased the distinguished Viennese antiquarian book establishment Gilhofer & Ranschburg at a bargain price.

Her last years were spent in flight. After the defeat of France, life in Paris became impossible for her and Arp. Together with the painter Albert Magnelli and his wife, Susi, they settled in Grasse, in the South of France; their friends the artists Robert and Sonia Delaunay were nearby in Mougins. They had all fought for the acceptance of abstract art. Now a much bigger battle was being waged. It is one of the fascinations of this story that Taeuber-Arp, Arp, and the Delaunays—two couples united less by the sacraments of marriage than by the sacraments of abstract art—were together in those dark days.

Robert Delaunay died in 1941. Sonia was invited to live with her friends. In 1942 Taeuber-Arp and Arp made their way back to Switzerland. It was there, staying at the home of the painter Max Bill, that Taeuber-Arp perished in the middle of a very cold night after turning on a stove that leaked gas. Shortly after her death, Kandinsky, with whom she had exhibited not long before in Paris, composed a salute to the artist and her work. “In order to possess the mastery of ‘mute’ forms,” he wrote, “one must be endowed with a refined sense of measure.” It was an extraordinary homage, coming from a man who by many accounts had been the first to make an abstract painting. Nobody’s sense of measure was more refined than Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s.

The one significant misstep in Mair’s biography comes at the end. Rather than leave the story with Taeuber-Arp’s death, she offers an epilogue in which she discusses Arp’s reactions to her death and his altogether honorable efforts in the years after the war to see that her work was cataloged, exhibited, discussed, and collected both in Europe and the United States. Perhaps it was inevitable that in the process of preserving his wife’s legacy, Arp made something of a myth out of her, transforming her into a guardian angel looking down on him from on high. Eventually Arp married Marguerite Hagenbach, a collector who had been a friend of both Arp and Taeuber-Arp; she outlived Arp and was energetic in her efforts on behalf of both artists’ legacies.

The problem with Mair’s epilogue is that it threatens to undermine the essential power of her book, which is that she enables us to see Taeuber-Arp on her own. By closing with Arp, Mair hands the story to him. It is a literary misstep, but not a fatal one. For nearly two hundred pages we have seen everything, including Arp, through Taeuber-Arp’s eyes. Nobody who painted with her indomitable clearheadedness could ever have been anything but the protagonist of her own story.

This Issue

March 7, 2019

The Migrant Caravan: Made in USA

The Man Who Questioned Everything