Since the early 2000s, journalism has been a precarious and embattled profession. The news industry has suffered staggering losses of revenue and employment, and journalists have become the targets of scorn and even hatred. The entire field has been politically reconfigured, as media outlets identified with different ideological positions provide their audiences with alternative versions of reality.

The profession’s fall from grace and the industry’s transformation have been all the more dramatic because of the advantages the news media enjoyed in the late twentieth century. Newspapers in most cities had consolidated down to one or two dailies, leaving the survivors with a near monopoly on print advertising in metropolitan markets. Although cable was making inroads, the three big broadcast networks still dominated television news. High-quality journalism itself was never very profitable in print or on TV, but it gave media organizations prestige and influence, and with their profits from advertising, they could afford it.

The monopoly held by the major news media also had the effect of marginalizing radical views on both ends of the ideological spectrum, creating the appearance and to some extent the reality of a broad bipartisan consensus in public life. Bolstered by healthy profit margins, the press was also able to cast itself as uncompromised by any commercial or partisan interest. Journalists and publishers who lived up to that standard of independence in the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the revelation of the Watergate scandal, and other great exposés became heroes.

This was the world that today’s older journalists knew when they were young. It was a world that concentrated power and profits but also enabled the press, insofar as its leaders were willing, to keep watch on government and business. David Halberstam’s The Powers That Be (1979), which focused on four exemplars of the era (CBS, Time Inc., The Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times), was a chronicle of that world at its height.

In the early stages of the digital revolution, the print media saw the new technology as a means of reducing production costs and expanding their audience, and they were so self-confident that they gave away the news for free online. But print circulation began falling, and as the Internet developed in the early 2000s, Google and sites such as Craigslist siphoned off ad revenue the newspapers had depended on, and Facebook would drain away more. The full force of the digital wave hit a decade ago, at the same time as the Great Recession, plunging many newspapers into bankruptcy and leaving others struggling to survive.

Yet there were promising signs too. New online media were creatively applying the unprecedented capabilities of digital technology, fostering new forms of public exchange, and receiving major infusions of capital. Since then, some of the new media organizations have begun to produce serious journalism and become genuine rivals to the traditional news giants, which have adapted to compete in the current environment. In the last few years, journalists who adhere to the profession’s norms have also had a revived sense of mission. Amid the torrent of lies from the highest reaches of government and disinformation on social media, journalism’s leaders are making unabashed claims that their business is “truth,” using that word without apology or qualification.

But because journalism has not been a lucrative business for some time, its ideals of truth-telling have become harder to uphold. The majority of digital ad revenue goes to Google, Facebook, and other companies that do not put it back into producing content; most newspapers no longer have the resources even for many of the routine stories they used to cover, much less for costly investigations. News organizations of all kinds are preoccupied with the new metrics of the digital economy and the old imperatives of revenue and profits. Survival depends on monetizing organizational assets, which in practice often means calling on editorial staff to work on business projects, ending the separation that was once a cardinal principle of journalistic ethics.

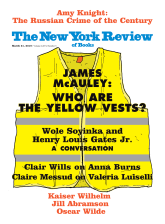

This tension between editorial autonomy and profit lies at the heart of Jill Abramson’s Merchants of Truth. Taking Halberstam’s book as her model, Abramson uses four news organizations—BuzzFeed, Vice, The New York Times, and The Washington Post—to tell the story of how journalism has evolved since around 2007, the point when newspapers began getting desperate and social media began taking off. The book has been dogged by charges of plagiarism and carelessness that have deflected attention from its argument. Several passages in the chapters on Vice all too closely follow other writers’ language; Abramson also got details wrong about a number of young journalists, making them appear inexperienced and unqualified. There is no excusing these failures, but not every damaged vessel should be sunk. For all its deficiencies, Merchants of Truth sheds considerable light on the news in this dark time; anyone who wants to understand what has been happening to journalism will learn a great deal from it.

Advertisement

Abramson is not a detached observer. She was in the thick of journalism’s crisis of survival as executive editor of the Times from 2011 to 2014, when she was summarily fired by the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr. Folded within Merchants of Truth is a personal memoir of her tenure that has inevitably drawn attention for its gossipy details and its significance in the age of women’s demands for equality in the workplace (she was the first woman to hold the Times’s top editorial post). But this is not what her book is about. Abramson believes she was underpaid and judged unfairly on sexist grounds, yet she also acknowledges so many limitations and mistakes of her own that she makes a fairly strong case for Sulzberger’s decision to replace her. What connects her personal story to the book’s larger theme is that she frames her difficulties as arising chiefly from the pressure at the Times to prioritize business concerns.

To broaden her account beyond the struggles of the traditional press, Abramson recounts the seemingly improbable transformation of two media upstarts into important journalistic outlets. BuzzFeed and Vice have followed a course that actually has old precedents. Innovation in the media often comes from the bottom of the market in cheap forms that the established institutions initially regard as unserious and vulgar. The penny press in the 1830s and later popular newspapers won mass audiences by catering to their readers’ emotions, inventing new genres such as crime reporting, and adopting visually arresting changes in graphic design.

BuzzFeed was the brainchild of Jonah Peretti, who as a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab had become interested in what he called “contagious media.” He first made a name for himself as one of the founders of The Huffington Post, where his mastery of techniques for gaming Google searches was invaluable in boosting traffic for the startup’s cheap fare, mostly celebrity posts and rewrites of stories from other news outlets. He then saw an opportunity for a new media enterprise based on the viral spread of memes, and in 2006 set up BuzzFeed, originally as a laboratory for creating the tools to detect trends in online sharing faster than anyone else. This was just as Facebook was emerging: “It’s like we happened to start surfing a few minutes before a great wave rolled in,” Peretti said.

When BuzzFeed began offering content, it had no pretensions to journalism, aiming instead to get people to share its cat videos, weird news items, quizzes, and listicles. (Criticized for relying so heavily on lists, Peretti defended them as “an amazing way to consume media,” citing the Ten Commandments and the Bill of Rights.) BuzzFeed’s staff competed not just to go viral but to go “mega-vi”; no website was better at creating million-view posts out of likable or, even better, “relatable” trivia. Abramson mentions that BuzzFeed even discovered an emotion for which no word exists in the English language: “the feeling of having one’s faith in humanity restored.” Posts conveying that feeling went mega-vi. Whether BuzzFeed itself at that point restored one’s faith in humanity was another matter.

Vice, which began as a counterculture paper in Montreal in the 1990s (its founders eventually moved it to New York), appealed to entirely different emotions. It sought to be edgy and provocative, oblivious to political correctness, and indeed intentionally offensive with articles like “Was Jesus a Fag?” and a “Racist Issue” featuring stereotypical racial images. Of Vice’s three cofounders—Shane Smith, Gavin McInnes, and Suroosh Alvi—McInnes was the one responsible for many of the provocations until his colleagues forced him out; he went on to found the Proud Boys, a far-right white-nationalist, antifeminist group. Smith was the dominant force in turning Vice into a media empire. His vision, Abramson writes, was for Vice to be “a bad-boy brand,” but it was also a “laddie magazine” that was somehow a “bible for hipsters” too.

From these unpromising beginnings, BuzzFeed and Vice became respectable enterprises with high ambitions. In 2011 Peretti brought in Politico’s Ben Smith as news editor and gave him the budget to hire accomplished young journalists and a mandate to do news in a way that would be as relatable and shareable as BuzzFeed’s other content. Although BuzzFeed News at first specialized in little scoops that earned fleeting attention, Peretti authorized Smith to create an investigative reporting unit to do more substantial stories. In 2016, through the work of Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed also played a critical part in identifying and debunking “fake news” in its original sense as pure scams and fabrications. Vice’s move up the ladder of respectability came chiefly through its expansion into video and development of international reporting “from the edge,” often exotic and dangerous locations—even North Korea—where other news organizations would not go.

Advertisement

These undertakings were feasible only because BuzzFeed and Vice attracted capital from patient investors and advertising from major brands. With no tradition of strict separation between the editorial and business sides, both organizations created their own in-house staff to produce “native ads” that told stories in the same style as their editorial content and therefore had the same potential to be shared virally. For example, in a charming BuzzFeed video ad, “Dear Kitten,” an older, wiser cat explains to a newly arrived kitten the pleasures and dangers of the house, eventually describing the delicious Purina Friskies that humans magically unlock from armored cans. (That ad, a classic of viral advertising, has been viewed more than 30 million times on YouTube.) Vice’s video ads were so similar to its documentary reports that viewers could hardly tell the difference.

According to Abramson, BuzzFeed deleted posts that might offend sponsors, while Vice also killed stories or “sanitized” them when they jeopardized relationships with potential advertisers. The business of being provocative apparently did not include a readiness to provoke business. In one respect, these new practices were contagious; despite their misgivings, newspaper publishers were soon creating their own in-house agencies to produce native ads too.

By the early 2000s, financial pressures were forcing the owners of traditional media to sell or adapt. Several newspaper-owning families—the Chandlers of the Los Angeles Times, the Bancrofts of The Wall Street Journal, and the Ridders of Knight Ridder, for example—decided to cash in while they could, but the Sulzbergers at the Times and the Grahams at the Post held on. At first the Post seemed to be on a steadier course because of Katharine Graham’s purchase in 1984 of the Stanley Kaplan test prep company, which became a gold mine, at least for a while, by expanding into for-profit education. Meanwhile, the Times made a series of blunders, including the disastrous decision to pay $1 billion in 1993 for the Boston Globe, which it would be able to unload twenty years later for only $70 million. But the ensuing reversal of fortune is where Abramson’s story holds its main interest. Chiefly because of different decisions about their core news business, the Sulzbergers succeeded in righting the Times, while the Post floundered and the Grahams decided to sell.

The Post’s story, as Abramson tells it, is a case study in strategic short-sightedness. Determined to keep up the paper’s profit margins to satisfy shareholders, the Grahams—first Donald E. Graham, Katharine’s son, and then Katharine Weymouth, Don’s niece—made round after round of cuts in the newsroom. Don Graham also insisted on maintaining the paper’s focus on the local Washington area, rejecting advice to turn the Post into a global brand. In another bad decision, he turned down the proposal for what became Politico, which has developed into a formidable rival to the Post itself in Washington reporting. When Kaplan became implicated in the deceptive practices of the for-profit education industry and the Obama administration changed the rules for federal student loans, what had seemed like the Post’s salvation became a curse. Kaplan’s profits plummeted, and the Post’s entanglement with the company damaged the paper’s reputation. With no answer to the Post’s difficulties, the Grahams in 2013 turned to a buyer whom they trusted to uphold the paper’s traditions, Jeff Bezos, under whom it has rebounded.

In contrast to the Grahams, Arthur Sulzberger Jr. refused to make deep editorial cuts at the Times in the belief that if it maintained its standards, people would continue to pay to read it. The Times sold off its other assets, slashed its dividends, and cut its business staff. “Sulzberger was certain his paper could be ‘the last man standing,’” Abramson writes, “as long as he was careful not to damage the quality of the news.” Even though an initial effort in 2005 to establish a paywall on the website had failed, Sulzberger took the risk of imposing one again in 2011, this time with a design that allowed free access for infrequent visitors but required regular readers to pay. The new paywall proved wildly successful, generating a new stream of income from digital subscriptions.

But the financial pressures continued, and it was against that background that Abramson’s conflicts with Sulzberger developed, especially over the pressure for closer collaboration between the editorial and business staffs. Abramson objected to journalists being “distracted from their work by endless meetings with product managers” who were trying to come up with money-making ventures such as apps and sponsored events. None of the incidents she relates, however, appear to have involved decisions that compromised the paper; her struggles with Mark Thompson, the Times CEO, were as much over turf as principle. She resented being imposed upon. During a discussion with Sulzberger and Thompson about apps for monetizing the Times’s content, she “snapped” at Thompson: “If that’s what you expect, you have the wrong executive editor.” Although she claims that she was unwilling to sacrifice her “ethical moorings for business exigencies,” it’s not clear that any ethical sacrifice was being asked of her.

Yet in writing her book, or perhaps not writing enough of it, Abramson has landed herself in an ethical controversy. Her critics have been hard on her, and it’s not surprising. A writer on lapses in journalism who becomes an illustration of the profession’s problems is like a preacher revealed to be a sinner. No one in the congregation will talk about anything else.

The sermonizer’s sins, however, are sometimes a distraction from bigger problems. The major limitation of Abramson’s book is that it offers too reassuring a picture of journalism. During her two years of work on it, she caught the Times and the Post on an upswing in their finances and BuzzFeed and Vice on an upswing in their editorial standards. In her conclusion, Abramson briefly discusses cuts in newsrooms elsewhere, but the general drift of the book is that things are looking up.

A wide-angle view would bring out a darker story. Newspapers around the country continue hurtling toward collapse, and digital media are not replacing them. Since 2004, according to a study by Penny Abernathy of the University of North Carolina, about 20 percent of newspapers have shut down, while many of the survivors have become what Ken Doctor of Harvard’s NiemanLab calls NINOs (newspapers in name only): diminished ad shoppers with hardly any local reporting. Private equity firms have bought many of these to suck the last profits from them. The new year has also brought editorial cuts in digital news media, including layoffs at both BuzzFeed and Vice.

While the Times and the Post may navigate the digital transition successfully, they belong to a limited class of national news organizations large enough to generate substantial subscription revenue from their readers. There is no sign that the digital market can support local or even regional journalism at anything like the level it had in print.

The picture of the news that Abramson provides is also too reassuring because it leaves out the radical transformation of the right. The problem is not just the omission from her book of any sustained discussion of the major right-wing outlets such as Fox; Abramson is also missing a larger change. When Halberstam wrote The Powers That Be, it made sense to focus on a few individual news organizations. Most Americans got their news from a paper they subscribed to, an evening news program they watched regularly, and perhaps a weekly news magazine. Now they get news from more diverse and only hazily known sources, and much of it via social networks.

In Network Propaganda, Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts illuminate this new “media ecosystem” through an analysis of how political news was linked, liked, and shared from 2015 to 2018 and how the news media either amplified or checked the diffusion of falsehoods. The study is based on four million political stories from 40,000 online sources, as well as case studies of conspiracy stories, rumors, and outright disinformation.

The pattern that emerges from the data contradicts the idea that there are two symmetrical echo chambers on the right and left. On the right, Benkler and his colleagues find an insular echo chamber skewed toward the extreme, where even the major news organizations (Fox and Breitbart) do not observe norms of truth-seeking. But from the center-right (for example, The Wall Street Journal) through the center to the left, they find an interconnected network of news organizations that operate under the constraint of established journalistic norms.

The result is two different patterns in how falsehood travels. On the right, major news organizations amplified stories concocted in the right’s nether reaches, such as Pizzagate (Democrats were purportedly operating a child-trafficking ring out of a pizza shop in Washington) and the Seth Rich murder conspiracy (an aide at the Democratic National Committee was killed supposedly because he divulged its e-mails to WikiLeaks). False stories originated on the left as well, but they were generally not relayed to a wider public. The right-wing media failed to correct falsehoods or to hold their journalists accountable for spreading them, whereas the rest of the media checked one another, corrected mistakes when they made them, and in several cases disciplined or fired those responsible for errors. These differences contributed to the greater susceptibility on the right not only to home-grown propaganda but also to Russian disinformation and commercially fabricated clickbait whenever these were consistent with what the authors call the “tribal narrative.”

The analysis in Network Propaganda does not, however, exonerate mainstream journalism from all that has gone wrong in the media. In 2016, Benkler and his colleagues argue, the right was able to “harness” the press to its cause because of journalists’ preoccupation with “balance” and eagerness for scoops. They note that the press had an institutional problem: How would it maintain balance if reporters did hard-hitting stories about Trump? Borrowing from a study by Thomas E. Patterson, they conclude that the solution was to run equally hard-hitting stories about Hillary Clinton. Journalists “performed” neutrality with harshly negative coverage of both candidates. In fact, according to Patterson’s analysis, negative coverage of Clinton outpaced positive coverage 62 percent to 38 percent, while coverage of Trump was 56 percent negative to 44 percent positive.

The interest of mainstream journalists in balance created a market for scoops about Clinton that the right was able to help satisfy. A clear instance of this pattern is the coverage of the Clinton Foundation. The Times entered into an arrangement that gave it advance access to Clinton Cash, a book by a Breitbart editor, Peter Schweizer, sponsored by a project founded by Schweizer and Steve Bannon and funded by Robert Mercer. The resulting Times article insinuated that in exchange for money for the Clinton Foundation, Hillary Clinton had enabled a Russian firm to acquire control of American uranium assets, even though the Times had no evidence that she had intervened in the decision to approve the deal, which a committee representing nine government agencies had made. The Times article and other overwrought and often misleading pieces in the mainstream press about the Clinton Foundation and the Clinton and DNC e-mails became some of the most widely shared news items in 2016, thus helping the Republican effort to depict Clinton and the Democrats as corrupt.

The negative mainstream coverage of Clinton, according to Network Propaganda, mattered far more than Russian disinformation to the outcome of the 2016 election. The authors’ point is not to deprecate the value of professional journalism, which they recognize is indispensable. Even though perfect objectivity is impossible and truth is “necessarily provisional,” Benkler and his colleagues write, truth-seeking organizations function differently from organizations set up to produce propaganda. While they are not always successful, the media that observe journalistic standards of truth make it possible to stop lies in their tracks. They give us some hope that a democratic society can reach a rational understanding of the world.

Yet the truth about our truth-seeking media, as Abramson’s book rightly emphasizes, is that they are also profit-seeking; our merchants of truth operate not only under journalistic norms but also under commercial constraints. When a publisher succeeds financially, as Sulzberger did, by protecting the quality of the news, we ought to celebrate that achievement as a victory for democracy itself. When an organization like BuzzFeed hunts down and exposes fabrications, that is a victory too. But when so much of journalism is at risk of disappearing and so many Americans inhabit a right-wing echo chamber, we ought to recognize that our country is in a crisis that strikes at its foundations.