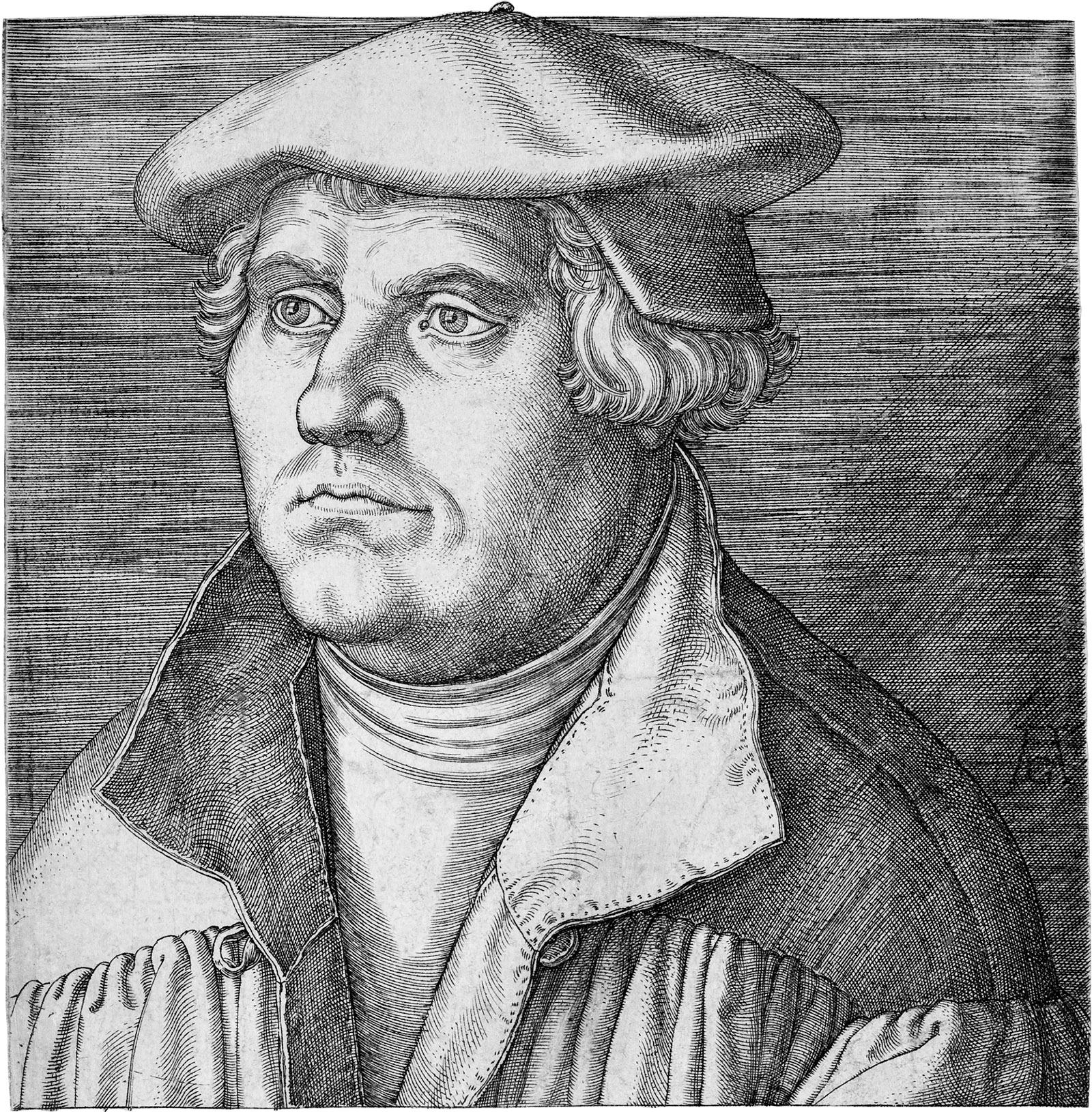

Most people in the West have heard of Martin Luther. Every Protestant is indebted to him for the fundamentals of their faith, and more than 80 million of them—close to ten million in the US—identify specifically as Lutherans. Luther’s vernacular writings, above all his translation of the Bible, have a fair claim to have forged a single German language out of a multitude of local dialects.

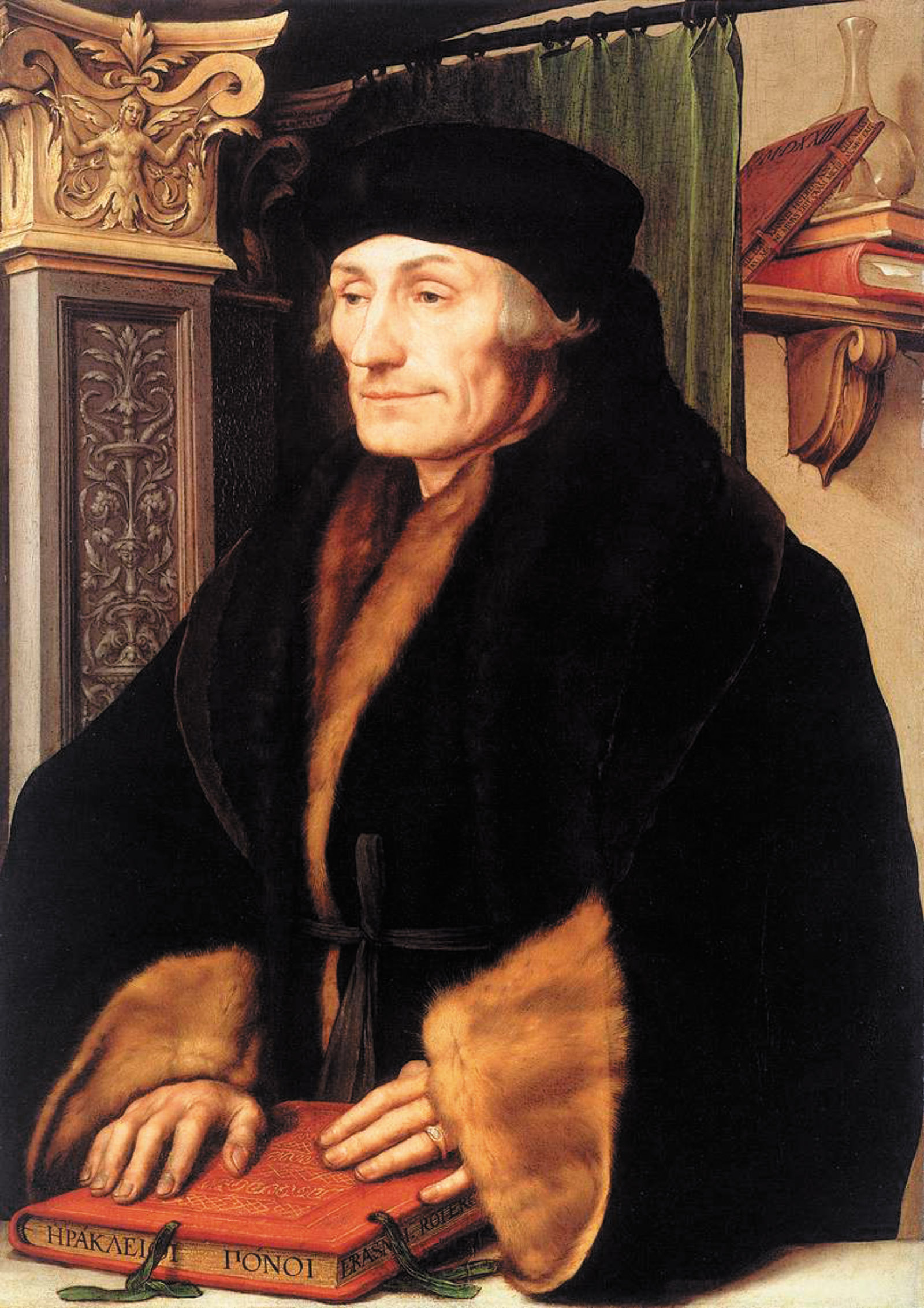

Desiderius Erasmus, by contrast, is now known mainly to scholars. Written almost exclusively in Latin, the international lingua franca of late-medieval Europe, the books that poured from the pen of this restlessly mobile citizen of the world were directed to the reform of his own era and have not aged well. Yet Erasmus was the sixteenth century’s most famous public intellectual and an international publishing sensation who formed close (and profitable) partnerships with the two greatest printers of the era, Aldus Manutius and Johann Froben.

The scope of his scholarship was breathtaking: textbooks of Greek and Latin, manuals for pious Christians, political treatises advising kings and rulers, pacifist polemics against the concept of a just war. These practical writings went alongside a stream of commentaries on and translations of Greek and Latin classics from Euripides to Seneca and the first multivolume collected editions of early Christian writers like Saint John Chrysostom, Saint Jerome, and Saint Augustine of Hippo. His Adages, an ever-expanding collection first published in 1500 of commentary and reflection on tags and proverbs culled from classical authors, pioneered a new literary form, the essay, and in its many editions (twenty-seven in his lifetime) was one of the most widely read books of the century. Entertained (and funded) by a succession of celebrity patrons—popes and princes, cardinals and bishops—Erasmus was an indefatigable networker, the list of whose correspondents included most of the leading writers and thinkers of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

Both Erasmus and Luther aspired to reform the church and, like every other intellectual of his generation, Luther acknowledged his debt to Erasmus’s pioneering scholarship. But in every other respect they were polar opposites: Erasmus’s intelligence was questioning, nuanced, and ironic, Luther’s explosive, confrontational, and supremely self-assured. And Luther would father a revolution that both built upon, but also spelled the ruin of, Erasmus’s life’s work. Michael Massing deploys his double biography, Fatal Discord, to explore the resulting murderous rift within sixteenth-century Christianity that—somewhat begging the question—we call “the Reformation,” and whose consequences, he argues, we are living with still.

Erasmus was born sometime in the late 1460s in Rotterdam, the illegitimate son of a priest learned enough to have copied both Latin and Greek manuscripts and a middle-class girl, possibly the daughter of a physician. Orphaned in his teens, he and his elder brother, Peter, were educated in schools run by the austerely devout Brethren of the Common Life, and he eventually followed Peter into monastic life as an Augustinian canon, a decision that he came bitterly to regret. Erasmus remained nominally a monk for the rest of his life but soon escaped the constraints of the cloister for a position as secretary to the bishop of Cambrai, who allowed his brilliant protégé to pursue theological studies at the University of Paris. Erasmus professed himself disgusted in equal measure by the old-fashioned scholasticism and the spartan living conditions of the university, and eventually adopted the precarious life of a freelance scholar, teacher, and writer.

The most influential cultural center of the day was Renaissance Italy, where the rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman literature, architecture, and philosophy seemed to offer vital resources for contemporary society. Erasmus eagerly embraced this humanistic scholarship but combined it with the earnest Christian preoccupations of his devout Dutch upbringing. His distinctive contribution to humanism was his search for a synthesis between the pagan literatures of antiquity and Christian civilization. The classics were not, for him, the domain of devilish error but a preparation for the Gospel; in them many of the values of the New Testament had been wonderfully anticipated, and by their wisdom and insight Christianity could be refined and renewed. One of the characters in a later dialogue by Erasmus would exclaim, only half jokingly, “Saint Socrates, pray for us!”1

In 1499 Erasmus made the first of many visits to England, where he was drawn into the circle of English humanists surrounding Thomas More and was befriended by John Colet, the leading English authority on the Greek texts of Saint Paul. Erasmus himself increasingly directed his scholarship to the texts of the Bible and the early Christian Fathers. He traveled to Italy, learned Greek, and became the leading exponent of the return ad fontes—to the ancient sources. He would spend much of the rest of his life scouring the libraries of Europe for ancient manuscripts of the earliest Christian writers, which he then edited and published.

Advertisement

Erasmus arrived at a distinctly moralistic account of true Christianity, which he understood as the devout “imitation of Christ” by loving obedience to his ethical teaching. The arcane doctrinal speculation of theologians and the elaborate ritual observances or extravagant asceticism of monks represented for him a Pharisaic preoccupation with mere appearances, at best superfluous, at worst compromising the luminous clarity of the true philosophia Christi. This “philosophy of Christ” had been first revealed to the unlearned and humble—women, children, uneducated fishermen. If Christians’ hearts were set on heaven and they tried to live by the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount, it did not much matter whether they understood the finer points of transubstantiation or the Trinity, or lit candles on pilgrimage, or kept the Friday fast (Erasmus himself, a lifelong hypochondriac, suffered from chronic indigestion and claimed to be allergic to salt fish, the staple of Catholics during Lent).

Erasmus became internationally famous for the profound classical learning of the Adages and for a devotional treatise, the Enchiridion Militis Christiani (Handbook of a Christian Soldier), an international best seller that ran through a hundred editions before the end of the century. But alongside Erasmus the sage and Erasmus the scholar, there was a contrasting figure, Erasmus the gadfly. In 1511 he achieved notoriety with the publication of Praise of Folly, in which he lampooned the absurdities and corruption rampant in politics, the law, the universities, and above all the Catholic Church. The book was completed in Thomas More’s house and teasingly dedicated to him (its title, Enconium Moriae, was a pun on More’s name and on the Greek word for folly). Through the mouth of Dame Folly, Erasmus satirized the ignorance and sterile ritualism of monastic life and denounced the greed of the clergy more generally. The book ended with a moving evocation of true Christianity as a form of divine folly, overturning worldly wisdom and ambitions for the single-minded pursuit of heaven. But it was the mockery in the rest of the book that delighted would-be reformers and outraged many within the religious establishment.

He further divided opinion with the publication in 1516 of his most influential scholarly work, the Novum Instrumentum omne, an edition of the Greek text of the New Testament with a facing Latin translation. For a thousand years the Western church had based its theology and pastoral practice on the Vulgate, the Latin translation of the Bible edited in the early fifth century by Saint Jerome. Jerome was one of Erasmus’s intellectual heroes, but he recognized that the Vulgate often misrepresented the meaning of the Greek original. In recovering that original, his new translation seemed to undermine important Catholic doctrines. For example, the Vulgate’s rendering of the angel Gabriel’s greeting to Mary in Saint Luke’s Gospel, “Hail, full of grace,” was used to underpin the doctrine of Mary’s sinlessness. Erasmus’s more accurate translation, “Greetings, O favored one,” removed one of the pillars of medieval devotion.

Equally alarming was his translation of the Greek word metanoia—not, as in the Vulgate, as “do penance” (a reading on which rested much of the church’s penitential discipline) but as the much less specific “repent.” Conservative churchmen were outraged at this challenge to ancient certainties, while humanists like More rushed to defend him as a loyal son of the church whose unrivaled wit and learning had been placed at the service of truth. The Novum Instrumentum was dedicated to Pope Leo X, a patron of humanists unfazed by Erasmus’s radicalism, but neither his friends nor his detractors had any inkling of the far greater religious challenge destined to destroy the unity of Western Christendom and, with it, the entire Erasmian project of gradual reform.

That challenge came in the winter of 1517 from an unknown young professor of biblical theology in the obscure university town of Wittenberg, in Saxony. Martin Luther, the son of a prosperous mine operator, had entered religious life as an Augustinian friar following a vow taken during a freak thunderstorm. Ardently and anxiously religious, he had come to see the mainstream of medieval scholastic theology as a barren exercise in logic, with no power to comfort or inspire. Close study of the Psalms and the Epistle to the Romans intensified his preoccupation with the gulf between God’s “righteousness” or justice and human sinfulness; immersion in the writings of Saint Augustine led him to seek resolution of this terrifying contrast not, as he had once thought, in the hectic pursuit of holiness by fasting, penance, and good works, but in simple reliance on God’s mercy.

Advertisement

This doctrine of justification by faith was in fact a commonplace of medieval theology, but it was obscured in practice by the medieval church’s emphasis on the strenuous pursuit of holiness. Luther radicalized it by making salvation an entirely passive process, in which human will and the practice of good works played no part. When in 1522 Luther translated the New Testament into German, he rendered Saint Paul’s assertion in Romans 3 that “man is justified by faith, without the works of the law” as “man is justified by faith ALONE, without the works of the law,” an apparently minor adjustment that in fact opened up a fundamental breach between Catholic and Protestant doctrines of salvation.

But in 1517 that gap was not yet apparent, even to Luther. He came to public notoriety with a more limited and practical protest. One of the more dubious features of late-medieval piety was the huge popularity of indulgences granted by popes or bishops in return for the performance of good works such as going on pilgrimage, or in return for charitable donations to good causes like bridges, churches, or hospitals. Indulgences were believed to remit the “temporal punishment” due to the justice of God after sin itself had been forgiven, and were claimed to be transferable to the dead, shortening the sufferings of the souls in purgatory. Such a potentially lucrative source of fund-raising was bound to be abused, and in 1517 an indulgence to fund the rebuilding of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome and promising lavish benefits was being peddled in Saxony by papal “pardoners.” Archbishop Albert of Mainz, who promoted the indulgence, was skimming off his own cut.

The Saint Peter’s indulgence struck at the heart of Luther’s struggle to reconcile divine mercy, justice, and the true cost of salvation. Outraged, he compiled a set of objections, intended as material for a formal theological debate. But these “Ninety-five Theses” were soon circulated in print and became an unlikely best seller in German as well as Latin. Luther’s denunciation of Roman racketeers picking German pockets caught a public mood. From the start of 1518, what had begun as matter for sedate academic discussion was firing controversy in the drinking shops and bowling alleys of Germany.

Rome was slow to recognize the threat posed by what at first seemed a local German difficulty stirred up by this frattelino, or little friar. When a formidable Dominican theologian, Cardinal Thomas Cajetan, was dispatched to Augsburg in October 1518 to persuade Luther to back down, the encounter proved a dialogue of the deaf, from which Luther fled in fear of imminent arrest. His targets widened and multiplied as he pursued the implications of the doctrine of justification by faith alone, challenging the church’s practice of penance, theology of the sacraments, and hierarchical authority.

In June 1520, at last grasping the seriousness of the threat posed by Luther’s rapidly growing celebrity, Leo X launched a formal excommunication. That same year Luther printed a series of manifestos that drastically reconfigured the whole structure of medieval Christianity. In an “Address to the German Nobility,” he insisted that every baptized Christian was a priest, and suggested the recruitment of clergy by popular election of “pious and learned citizens”; he dismissed medieval scholastic theology as a pagan aberration, proclaiming instead a theology exclusively derived from the Bible, and he claimed that the authority of the pope was “usurped,” calling on secular princes to take responsibility for the reform and regulation of the church. In “The Babylonian Captivity of the Church,” he reduced the number of sacraments from seven to three—baptism, eucharist, and confession—and denied that the Mass was a sacrifice. In “Concerning the Freedom of a Christian” (dedicated, with elaborate irony, to Leo X), he expounded his radical version of justification by faith, arguing that good works contributed nothing to the process of justification but rather flowed from it: men and women justified by faith alone inevitably excelled in goodness, as a fruit tree naturally bears its appropriate fruit.

Luther was a brilliant polemicist and the first religious leader to grasp the potential of the printing press; in his friend the painter Lucas Cranach, he also found an inspired visual publicist. Mass-produced prints by Cranach and his many imitators, depicting Luther as a haloed saint or a German Hercules, smiting cringing monks and popes, helped cement a heroic image of the reformer in the popular imagination. Luther’s drastic simplification of the Christian life, pitting Gospel freedom against oppressive human law, appealed to a downtrodden populace while, by contrast, his call to secular rulers to seize control of the asset-rich church appealed mightily to the princes of the Holy Roman Empire.

But the piously Catholic emperor, Charles V, took a different view. When in May 1521 Luther, summoned to appear before the imperial Diet at Worms, defiantly refused to recant his now openly “heretical” opinions, he was placed under imperial ban as an outlaw, and despite Charles’s guarantee of safe conduct left the Diet in fear for his life. On his journey back to Wittenberg he was “kidnapped” by masked friends employed by his patron, Duke Frederick, and spent the next two years in protective seclusion, disguised as “Junker George,” in the Wartburg castle in Eisenach, where he used his enforced leisure to translate the New Testament into resonant German.

Up to this point it was possible to see Luther and Erasmus as products of one and the same impulse for religious reform. Responding in his diary to Luther’s disappearance in May 1521, Germany’s greatest artist, Albrecht Dürer, recorded his anguish at the apparent death of “this God-illumined man” and prayed for another to take Luther’s place: “O Erasmus of Rotterdam, where art thou?… Ride forth by the side of the Lord Christ; defend the truth, gain the martyr’s crown!” Erasmus himself, though not made of the stuff of martyrdom, was initially sympathetic to Luther: in 1519 he wrote to Albert of Brandenburg to deplore the motives of those who branded Luther a heretic, and even after Leo X had issued the papal bull Exurge Domine against Luther in 1520, Erasmus encouraged Duke Frederick to go on defending his protégé, whose chief “errors,” he thought, had been “in attacking the crown of the pope and the bellies of the monks.”

Erasmus’s concern was to secure a fair hearing for a man who was being targeted by those who were also the enemies of humanism. Even while doing so, he discouraged his own publisher, Froben, from reprinting works by Luther, and he was careful to distance himself: “Christ I know, Luther I do not know…. They may eat him boiled or roasted, for all I care, but they mistake in linking him and me together.”2 In 1521, increasingly repelled by Luther’s populism, strong sense of personal infallibility, and confrontational nature, Erasmus set out his misgivings in a letter to one of Luther’s most prominent disciples, Justus Jonas. From the appearance of Luther’s very first publications, Erasmus explained, “I was full of fear that the thing might end in uproar and split the world openly in two.”

Prudent reform should be a gradual process, Erasmus wrote, but Luther in “this torrent of pamphlets” had poured everything out at once and given “even cobblers a share in what is normally handled by scholars as mysteries reserved for initiates.” There was about Luther “a sort of immoderate energy” that carried him “beyond the bounds of justice.”3 In 1523 Erasmus had declared “peace and unanimity” to be the “the essence of the Christian faith.”4 But Luther, he told William Warham, archbishop of Canterbury, had been sent into the world by “the genius of discord,” and his movement had brought “good learning into ill repute.”5

Erasmus’s horror at Luther’s propensity to “tumult” and “sedition” was confirmed by the German Peasants’ Revolt of 1524–1525. That bloody, popular uprising was in part inspired by Luther’s rhetoric, though Luther himself, who was as socially conservative as he was religiously radical, savagely repudiated it, calling on the authorities to “smite, slay, and stab” the “murdering and robbing bands of peasants,” which put an abrupt end to plebeian support for his reforms.

Pressure from every quarter forced Erasmus to declare himself openly for or against the reformer. Recognizing that his own good standing in the church was at stake, in 1524 Erasmus at last reluctantly published against Luther, choosing an issue on which they held deeply opposed views, the role of human free will in salvation. Like Luther, Erasmus laid great emphasis on the grace of God as the prime agent of salvation. But Luther had argued that righteousness was “imputed” by God to human beings, who remained passive in the process, and Erasmus’s strongly ethical reading of Christianity gave a significant responsibility to human cooperation with God’s grace. He wholeheartedly endorsed the church’s immemorial teaching that grace perfected human nature, rather than annihilating or negating its faculties. For Luther human faculties had nothing to do with salvation: no human being was free to choose God: instead, God predestined to salvation those whom he wished to save, not for any virtue of theirs, but by a supreme act of divine freedom.

In the subsequent debate “On the Bondage of the Will,” Erasmus presented himself as the sweetly reasonable advocate of a middle position between Luther and his opponents. He emphasized scripture’s obscurity with respect to high mysteries like predestination, about which a reverent agnosticism was the best attitude: to insist on it was to make God an arbitrary tyrant, and humans could not say with certainty what God’s true nature was. Luther was having none of this: on fundamental issues, he insisted, scripture was always clear, and Erasmus’s eirenic nondogmatism was a form of apostasy: “Take away assertion and you take away Christianity.” Erasmus became for Luther a frequent object of scorn, a “Judas” and “atheist” whose feeble pretense to reasonableness elevated human wit over the Word of God and reduced Christianity to the status of “a fairy story.” “This I bequeath you as my testament when I am gone,” Luther once declared,

and I call you present as witnesses of this, that I hold Erasmus for the greatest enemy of Christ there has been this thousand years…. The reason I hate Erasmus with all my heart is that he brings into dispute the things that ought to be our joy.6

Until his death, Erasmus was convinced that he had got the better of the argument with Luther. But Luther’s bludgeon proved more effective than Erasmus’s scalpel. Religious alliances such as the polarized Holy Roman Empire descended into confessional war. Erasmus’s aspiration for the gradual and peaceable reform of the church by the spread of classical learning and the impact of impish satire seemed increasingly both unrealistic and suspect. Erasmus’s closest friend, Thomas More, turned heresy-hunter and publicly expressed regret for the comfort his own youthful satires might have given to enemies of the church. Not so Erasmus, whose motto was “I yield to no one,” and who refused to reject or be deflected from his life’s work. In 1526, at the height of his confrontation with Luther on behalf of the church’s teaching, he infuriated conservative Catholics by publishing new colloquies pillorying the greed, superstition, and exploitation of the religious orders, and satirizing the bogus relics and religious extravagances practiced at England’s two greatest shrines, Walsingham and Canterbury.

Michael Massing tells the story of this momentous “bifurcation” in Western thought with vividness and panache, though his book would have benefited from being half the length, and he recycles some old myths, like Luther’s alleged posting of the Ninety-Five Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. He follows Max Weber’s classic thesis in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by arguing that Luther’s ideas contributed directly to the emergence of a radical Protestant individualism and a social order “characterized by competition and self-expression, entrepreneurship and free enterprise.”

Erasmus’s influence he sees as more elusive but, one deduces, more benign. Despite his insistence on his loyalty to Rome, Erasmus was believed by many to have “laid the egg that Luther hatched.” In the hardening ideological conflicts of the later sixteenth century, his ideas were condemned by successive popes, and within a generation all his writings were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books. His real influence for Massing lies outside the sphere of organized religion, his most significant disciple being the Jewish philosopher Benedict Spinoza, who “recast” Erasmus’s rationalism, skepticism, and toleration for the theistic age of the Enlightenment, “stripping the ‘Christian’ from the Christian humanism that Erasmus had expounded” and proclaiming “freedom of belief in a democratic system.”

Here Massing assumes too readily that the essence of Erasmus’s message could be detached from its Christian and, indeed, Catholic setting. Like Thomas More’s, his sense of human solidarity was inextricable from his belief in the unity of the church as sacrament and sign of that wider unity. One of his central preoccupations, barely touched on by Massing, was the indispensable role of the consensus fidelium, the consensus of believers in discerning the truth, and one of his main objections to Luther was the reformer’s willingness to pitch his own novel certainties against the collective wisdom of the community. For Erasmus, colloquy, the calm and receptive exchange of thought, was no mere emollient but a fundamental tool in the pursuit of truth. In the church and its traditions he saw a colloquy that stretched across the world and back to the apostles. In that important sense, for all his emphasis on tolerance, he was an enemy of individualism.7

But for Massing, during the Enlightenment Erasmian values, though often unacknowledged, were in fact widely embraced. And in the twentieth century, Erasmus’s “rationalist, ethics-based, pluralistic, and internationalist creed” was a beacon for opponents of Nazi authoritarianism and continues to inspire liberal thought, underlying the ideals, for example, of the European Union and, it is to be assumed, American liberalism as well. Massing, we can conclude, believes that the voice of reason is sadly too often drowned by the voice of passion, as vulnerable now as in the sixteenth century. “If humanists think that their own values represent those of all humanity and offer the best design for living,” he tells us, “they should be able to do a better job [than Erasmus] of making that case.”

-

1

“The Godly Feast,” quoted in C.A. Patrides, “Erasmus and More: Dialogues with Reality,” The Kenyon Review New Series, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter 1986), p. 34. ↩

-

2

Erasmus, edited by Richard L. DeMolen (Hodder and Stoughton, 1973), p. 131. ↩

-

3

James McConica, Erasmus (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 71. ↩

-

4

In the preface to his edition of the writings of Saint Hilary; see McConica, Erasmus, p. 77. ↩

-

5

DeMolen, Erasmus, p. 134. ↩

-

6

Richard Rex, The Making of Martin Luther (Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 214–215. ↩

-

7

On all this see Brian Gogan, The Common Corps of Christendom: Ecclesiological Themes in the Writings of Sir Thomas More (Brill, 1982), and McConica, Erasmus, pp. 74–80. ↩