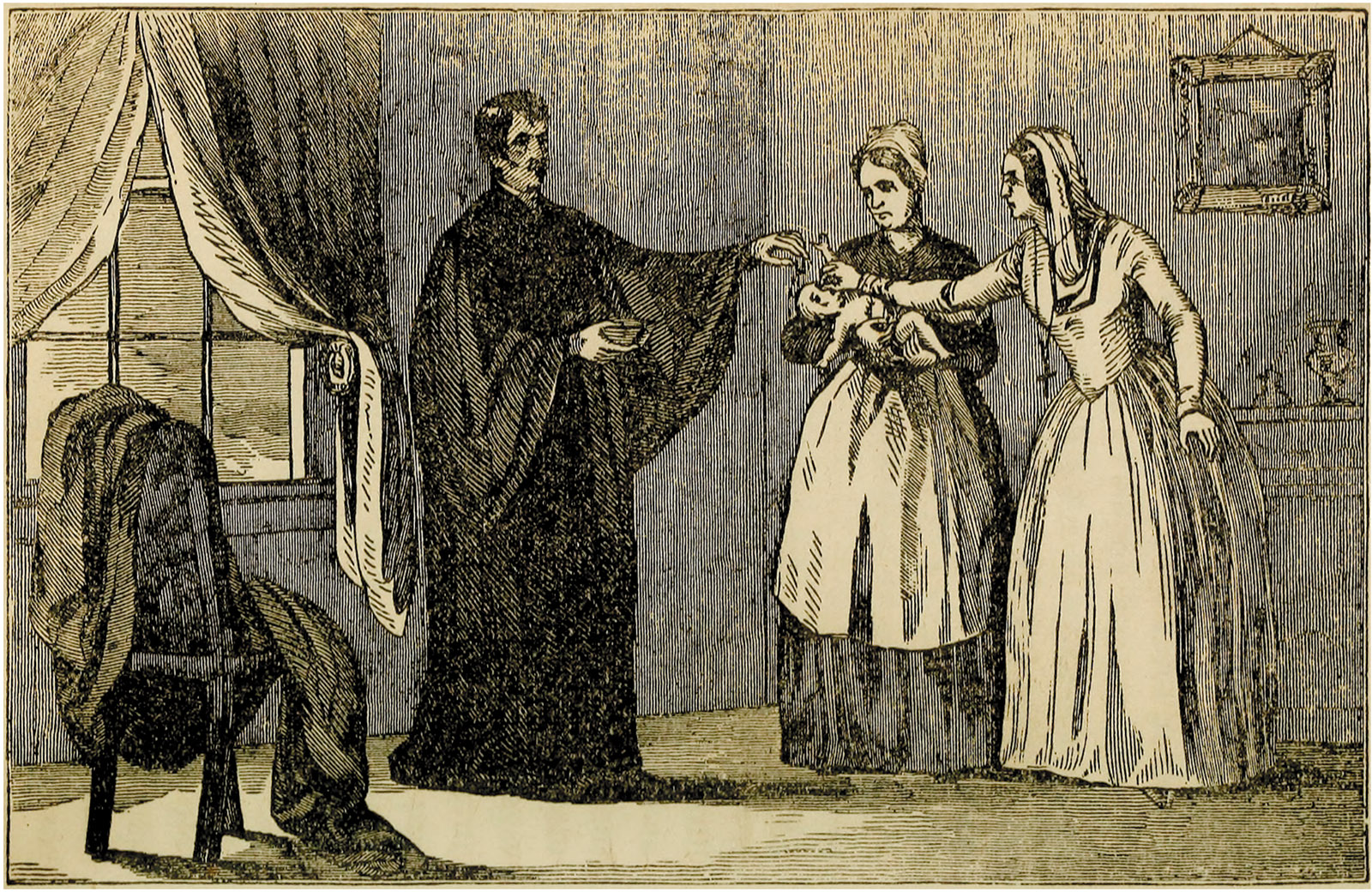

In the early 1830s, the Hôtel-Dieu nunnery in Montreal was reportedly the site of illicit sex and mass murder. Lecherous priests from a nearby seminary snuck in through a secret tunnel and forced themselves on nuns. Scores of babies were born, baptized, strangled, and cast into a cellar. Lime was spread over the tiny corpses to speed their decomposition.

These stories appeared in Awful Disclosures, by Maria Monk, of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal (1836), which became an instant best seller in the US. Its purported author, the “escaped nun” Maria Monk, claimed that the horrors she had witnessed in the nunnery had impelled her to flee. She wrote that she was so distraught by her experiences there that she twice attempted suicide. After escaping from the nunnery, she made her way to New York, where Protestant ministers helped her publish her narrative.

The book was a sham, perpetrated by minister friends of Monk’s. Its ghostwriter was most likely the Reverend George Bourne, who ran a nativist newspaper and had previously written a similarly salacious anti-Catholic exposé. Investigations of the nunnery yielded no evidence of the kind of behavior Monk had recounted. The respected Colonel William L. Stone, an influential New York journalist and public official, inspected it with Awful Disclosures in hand and concluded that she was never a nun but rather “an arrant imposter”; her book was “a tissue of calumnies,” and “the Priests and Nuns [were] innocent in this matter.” Monk’s mother testified that she had suffered brain damage as a child when she ran a pencil into her head and had drifted into prostitution as an adult. Monk had been living in a Montreal asylum for “fallen” women during the seven years she supposedly was at the nunnery. Exposed as a fraud, she sank into obscurity and poverty. In 1849, at thirty-two, she was living in an almshouse in New York when she was arrested for theft. She died in a penitentiary shortly thereafter.

The revelation that Awful Disclosures was a hoax concocted by Protestant men trying to stoke nativist fears of Catholics did not prevent the book from selling more than 300,000 copies before the Civil War and remaining in print to this day. It attained, as one historian writes, “the questionable distinction of being the ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin of Know-Nothingism’”—a prominent anti-Catholic nativist movement.

As Cassandra L. Yacovazzi shows in her lively book Escaped Nuns, Awful Disclosures was a typical example of the anti-Catholic literature that captured the popular imagination during the antebellum period, when over twenty best-selling convent tales appeared. Among them were The Escaped Nun, The Female Jesuit, Priests’ Prisons for Women, The Captive Nun, The Haunted Convent, The Convent’s Doom, and Celia; or, The White Nun of the Wilderness. Such books, Yacovazzi points out, often featured women held as sexual prisoners by lustful priests in nunneries that had labyrinthine passages, trap doors, and rooms used as torture chambers. Those behind the publication of anti-Catholic books before the Civil War were, in the main, Protestant ministers who wanted to portray Catholicism as a dangerous religion that was poised to destroy American institutions.

At different times in American history, members of various religions or nationalities—Quakers, Jews, French, Chinese, Italians, Japanese, and, most recently, Muslims and Central Americans—have been targeted for restrictions on immigration or expulsion from the country. For American nativists of the pre–Civil War period, the surge in European immigrants—many of them Roman Catholics from Ireland and Germany—stirred deep anxiety. The number of European arrivals rose from 60,000 in 1832 to an average of nearly 400,000 annually between 1847 and 1854. Catholics, who had had only a small presence in America in 1800, had become the largest single religious group in the nation by 1860.

From the perspective of conservative Protestants, a Catholic takeover of the US seemed imminent. Anti-popery, the driving force in Protestantism from its beginnings, gained strength after 1830, when the spike in Catholic immigration fueled paranoia that was expressed in literature made widely available because of advances in printing technology and distribution. Besides books, nativists published newspapers with titles like The American Protestant Vindicator, Priestcraft Unmasked, The Anti-Romanist, and The Downfall of Babylon; or, The Triumph of Truth Over Popery.

Anti-Catholic literature has been previously investigated by cultural historians, but Yacovazzi is the first to consider the stories of escaped nuns in comparison to other forms of popular writing, such as lurid “city mysteries” novels and anti-Mormon writings. She analyzes numerous unfamiliar works, including anti-Mormon novels like The Mormoness; or, The Trials of Mary Maverick, The Prophets; or, Mormonism Unveiled, Wife No. 19; or, The Story of a Life in Bondage, Being a Complete Exposé of Mormonism, and the inevitable Awful Disclosures of Mormonism. Sexual bondage, infanticide, and the miseries of plural marriage were common topics in them. One novel, Mormon Wives, sold more than 40,000 copies in the 1850s. By 1900, over fifty anti-Mormon books were in print.

Advertisement

All such works, Yacovazzi argues, revealed the hazards that middle-class women faced when they abandoned the role then assigned to them—that of the pure, pious wife and mother. In her view, the era’s sensational writings served as advice manuals on avoiding tempters, such as lascivious Catholic priests, seductive urban roués, and magnetic Mormon men.

It is fortunate that Yacovazzi does not lean too heavily on this thesis, for the scandalous material she studies comes closer to offering escapist thrills than instruction for women. For those who needed training in motherhood and domesticity, there were plenty of religious tracts, sentimental novels, and housekeeping guides. The literature Yacovazzi discusses operated most powerfully as titillating exposés of alleged religious and social corruption. City-mysteries novels, written by authors like George Lippard and George Thompson, portrayed ruling-class figures—preachers, lawyers, bankers, moguls—as hypocrites who indulged in private debauchery. Anti-Mormon novels emphasized the alleged depravity of Joseph Smith’s followers, who engaged in what most Americans saw as the unthinkable practice of polygamy.

Anti-Catholic works in particular reached bizarre extremes. For example, Samuel B. Smith’s Rosamond Culbertson described Catholic priests in Cuba who kidnapped young African men for the purpose of killing them and making sausages out of them—a story parodied in John T. Roddan’s John O’Brien (1851), in which Protestant boys are cast into a meat grinder, producing “half a mile of sausages…reserved for the eating of priests and nuns.”

Some of the most suggestive passages in Yacovazzi’s book trace the historical background of anti-Catholic literature. She writes of the novices Elizabeth Harrison and Rebecca Reed, who fled the Ursuline convent on Mount Benedict in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in such a distraught state that rumors spread locally of sexual deviance and torture there. Aroused to a frenzy, a Protestant mob burned the convent to the ground, desecrated the surrounding property, and exhumed corpses from a Catholic cemetery, playing with nuns’ bones and pulling teeth from skulls to keep as souvenirs. Reed capitalized on her experience by writing Six Months in a Convent (1835), whose stories of severe penances, women held captive, and plots to extend the power of the pope wildly exaggerated the demanding regimen and harsh treatment she had endured at Mount Benedict.

The incident generated a parody of escaped-nun narratives, Norwood Damon’s The Chronicles of Mount Benedict (1837), in which the Charlestown convent became the scene of revelry, torture, and child murder until a group of Protestants, appalled by the smell of roasting human flesh, attacked and destroyed it. Damon explained that American readers ignored works of “plain common sense and truth,…but give them some awful, nasty disclosures, by Maria Monk, or some other whorish, wild, improbable, bugbear story, and they will gullup it all down voraciously, and lick their lips with ineffable gusto.”

Yacovazzi mentions the rise of the Know Nothing Party (aka the American Party) but doesn’t provide much detail about nativist politics. The American Party, which warned that the pope was trying to take over America and destroy its institutions, called for banning Catholics from public office, deporting foreign vagrants and criminals, and requiring a twenty-one-year naturalization period for immigrants. By 1854, the party had around one million members nationally and elected several governors and hundreds of state legislators and the mayors of Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia, as well as inciting political riots that killed over seventy people and wounded several hundred. In light of the remarkable political success of nativism in the 1850s, it would be interesting to know more about its connections with the scabrous literature Yacovazzi discusses. Nevertheless Escaped Nuns merits praise for the breadth of its coverage of this literature and for Yacovazzi’s suggestions of just how intense cultural fears can become.1

The fear that runs through Catherine O’Donnell’s Elizabeth Seton: American Saint is of an altogether different kind. One might think that Seton, the first American-born citizen to be canonized by the Catholic Church, led a life of harmony and peace. Not so, according to O’Donnell: “Her spiritual life brought not peace but dread.” This was the case even after Seton had achieved international fame as a leader of Catholicism in America. At forty-six, stricken with tuberculosis and approaching death, she refused water despite her intense thirst in order to fast at night so that she could receive Communion. Until the very end, she fixed her eyes on heaven, fearing the consequences if she deviated even slightly from her course. “If I am not one of [God’s] Elect,” she murmured on her deathbed, “it is I only to be blamed.”

Advertisement

Seton’s life story has been told several times, most notably in Annabelle Melville’s Elizabeth Bayley Seton, 1774–1821 (1951) and, more recently, in Joan Barthel’s American Saint: The Life of Elizabeth Seton (2014). O’Donnell adds human depth and historical background to the life. Her elegantly crafted biography is a worthy testament to a woman widely respected as the founder of parochial education and Catholic social work in America.

Born in 1774 on Manhattan Island, then largely rural, Elizabeth Ann Bayley grew up in the Anglican Church, which became the Episcopal Church after the American Revolution. Her father was a doctor. When she was three, her mother died, possibly due to complications from childbirth. Her father subsequently married a woman from whom Elizabeth and her sister eventually became estranged.

In her childhood and early adolescence, Elizabeth was curious, reflective, and given to mood swings. She read the skeptical writings of freethinkers like Voltaire and Rousseau, which led her to question institutional religion and to regard ethical action as the surest path to fulfillment. She joined a society devoted to helping poor widows and small children.

In 1794, at nineteen, she married the twenty-five-year-old William Magee Seton, a well-to-do businessman in the import trade. The couple settled into a respectable life in Manhattan and had five children. A caring wife and mother, Elizabeth was increasingly devoted to Episcopalianism. Her spiritual guide at the time was John Henry Hobart, an assistant rector at Manhattan’s Trinity Church (he later became the bishop of New York).

Severe adversity tested Elizabeth’s religious faith. Several of her family members died. William declared bankruptcy when his mercantile firm failed. He also suffered from tuberculosis. Hoping that a warm climate would restore him, he, Elizabeth, and their eldest daughter sailed in the fall of 1803 to Livorno, Italy, where he had business partners. On their arrival, he was quarantined because he showed symptoms of contagious disease. Elizabeth lovingly nursed him, but he soon died. During this dark time, she became dissatisfied with Protestantism and struggled to maintain her faith. In Italy, she attended Catholic services that inspired her to accept transubstantiation, the belief that the bread and wine dispensed at Holy Communion was truly, not just figuratively, the body and blood of Christ.

After returning to America, Elizabeth joined the Catholic Church in 1805. Four years later, she moved to Baltimore to open a school for girls, along with companions who took their vows from the archbishop of Baltimore, John Carroll. The women formed the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s, the first American-based Catholic sisterhood. After a few months, they moved their school to Emmitsburg, Maryland, a bucolic hamlet near the Pennsylvania border. Accepting both Catholics and Protestants of various social backgrounds, St. Joseph’s Academy for girls and Mount St. Mary’s College, Elizabeth’s boarding school for boys, gained fame for their openness and educational excellence.

Now known as Mother Seton, Elizabeth founded a religious order that in July 1813 was officially named the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s, an American version of France’s Filles de la Charité, founded by Saint Vincent de Paul in 1633. Soon the Sisters of Charity had branches in Philadelphia and New York, and by the time of Elizabeth’s death in 1821 the Sisters numbered fifty women. In 1850 the order began collaborating with the Daughters of Charity of Paris, and over time the Sisters and the Daughters of Charity founded schools, orphanages, hospitals, child-care institutions, and programs for visiting the homes of the poor. Today it forms an international network devoted to aiding the vulnerable and the marginalized.

O’Donnell writes of Seton that “in her life we…see unmistakable evidence that anti-Catholic sentiment was less pervasive and monolithic in the early American republic than is commonly portrayed.” The crucial phrase here is “in her life.” Seton died more than a decade before the virulent anti-Catholicism that inspired books like Maria Monk’s burst upon the cultural scene. This is not to say, however, that Seton did not encounter resistance after her conversion to Catholicism. To the contrary, as O’Donnell vividly recounts, there was a “boiling cauldron” of hostility toward her among her Protestant friends and her extended family. John Henry Hobart, her erstwhile counselor, was stunned by her religious turn. Confessing that he was “deeply affected,” he wrote an eighty-page tract in response to a screed by Seton’s Italian adviser, Filippo Filicchi, who had encouraged her to embrace Catholicism. Hobart denounced Catholicism’s “corrupt and sinful communion,” which, he insisted, was “abhorrent to reason, to our senses, and to our feelings.” Though moved by Hobart’s plea, Seton felt that the eternal fate of her and her children was at stake. She rejected the Protestantism of her time, which associated getting to heaven with being swayed by powerful sermons, such as those she had heard Hobart give.

But she did not escape anti-Catholic sentiment even in her pastoral Emmitsburg retreat. Her brother-in-law Governeur Ogden wrote that her new faith consisted merely of “senseless addresses to wooden images or imaginary saints.” The Catholic religion, he fumed, “is uncongenial to the habits, manners, and nature of Americans and ere long I predict from many causes, the demolition of every building in that state in any wise resembling a convent or Catholic hospital.” Yet she remained unshaken. She wrote a friend, “You will hear a thousand reports of nonsense about our community which I beg you not to mind. The truth is we have the best ingredients of happiness—order, peace, and solitude.”

On the topic of Catholicism as a refuge for formerly anxious Protestants like Seton, O’Donnell misses an opportunity to make broader comments on American religion. At one point she insightfully compares Seton to the author and reformer Orestes Brownson, who, like her, turned from Protestantism and freethought to Roman Catholicism. But O’Donnell could have supplied more information about American Protestant converts to Catholicism, of which there were thousands in the course of the nineteenth century. The ferment caused by religious freedom in the young democracy generated an array of offshoots of Protestantism. Emerson caught the free religious spirit of America when he wrote, “The Protestant has his pew, which of course is only the first step to a church for every individual citizen—a church apiece.”

Religious leaders swayed by evangelical Protestantism included Robert Matthews (aka Matthias), who was inspired by a religious revival and soon gained a cult following when he proclaimed himself God the Father; Jacob Cohran, who announced that he could raise the dead, heal the sick, and cast out devils; Jemima Wilkinson, whose followers considered her the Messiah; and Jacob Osgood, who said God had told him to warn sinners to flee the wrath to come. Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, had reportedly caught a religious “spark” at a Methodist camp meeting in the “Burned-over District” of upstate New York; he claimed that, later, under the guidance of an angel, he discovered golden plates that he translated into the Book of Mormon. Among the sects that sprang up were many varieties of Baptists, including Primitive Baptists, Free-Will Baptists, Hard- and Soft-Shell Baptists, Particular Baptists, Six-Principle Baptists, Anti-Mission Baptists, Two-Seed-in-the-Spirit Predestinarian Baptists, German Seventh-Day, Close-Communion, General, Sabbatarian, and Foot-Washing Baptists—all with different emphases in doctrine.

America became, in the words of the novelist Catharine Sedgwick, “a country…where old faiths are every year dissolving, and new ones every year forming.”2 Foreign visitors commented on the phenomenon: Alexis de Tocqueville noted the nation’s “infinite variety of ceaselessly changing Christian sects,” and the British tourist Frances Trollope noted that Americans “appear to be divided into an almost endless variety of religious factions.” In this dizzying atmosphere, Catholicism, with its long-established rituals and traditions, offered security to many restless seekers. It would have been useful had O’Donnell considered Seton more fully against this background.

There is also the issue of Catholicism and slavery. O’Donnell informs us that Mother Seton’s Emmitsburg establishment was served by enslaved people—between ten and fifteen in a given year. Her major funders in Maryland were slave owners. It would have been helpful if O’Donnell had discussed the broader picture of Catholicism and slavery. The harsh truth is that, despite an anti-slavery bull issued in 1839 by Pope Gregory XVI, most American Catholics—with notable exceptions like Orestes Brownson and John Baptist Purcell, archbishop of Cincinnati—either condoned slavery or remained silent about it. During the Civil War, Southern Catholics loathed Lincoln and his antislavery agenda. The Catholic archbishop of Baltimore excoriated the “horrible and detestable” Emancipation Proclamation, which, he insisted, was “letting loose from three to four millions of half civilized Africans to murder their Masters and Mistresses!”3

Catholics, of course, were hardly alone among American Christians who supported the South’s peculiar institution. Seton’s non-Catholic maternal grandfather and father-in-law had both held slaves in New York. But her continued indifference to slavery gives us pause. O’Donnell writes, “Elizabeth gave no thought to the institution that supported the Catholic society to which she’d moved.” Though she said she was overjoyed “at the prospect of being able to assist the Poor, visit the sick, comfort the sorrowful, [and] clothe little innocents,” she ignored the ongoing wretchedness and suffering of America’s enslaved millions.

In this respect, she differed notably from the anti-Catholic figures of her day, most of whom were abolitionists. For all their sensation-mongering, clergymen like George Bourne were devoted to fighting not only popery but also slavery. As Yacovazzi notes, it was a short step from exposing Catholicism’s restrictions on women to highlighting slavery’s mistreatment of them. Bourne, lamenting that the female slave had “no means of defense or escape” from her master’s “unbridled passions,” wrote, “Slavery! Thou art the mother of harlots and the abominations of the earth!” Small wonder that the antislavery Lincoln, while he opposed Know Nothingism, won support from anti-Catholic leaders, one of whom, Joseph Flanigan, assured him that his election would destroy both “the Slave Power of the South and the Roman Catholic Power of the North.”

Another question related to Seton involves her canonization. When Pope Paul VI announced her sainthood in 1975, he identified miracles she had performed. The church at the time required that a candidate for sainthood have four authenticating miracles to qualify, but Paul allowed for three in Seton’s case. He credited her with curing a man with a rare brain disease, a Daughter of Charity stricken by pancreatic cancer, and a girl who had acute lymphocytic leukemia. These cures occurred in hospitals associated with the Sisters of Charity: the cancer cure in New Orleans in 1935, the leukemia cure in Maryland in 1952, the brain disease cure in Yonkers in 1963. Although O’Donnell mentions that these cures occurred in the twentieth century, she appears to credit them implicitly without explaining the pope’s reason for assigning them directly to Elizabeth Seton. The healings are surely an important part of Elizabeth’s biography; indeed, they are the justification for her canonization. It would seem important to discuss the evidence—or lack thereof—for the cures, and to probe the pope’s attribution of them to someone long dead.

With or without miracles, Seton emerges from O’Donnell’s biography with her exalted status intact, if we attribute her indifference to slavery to typical Catholic attitudes in her era. For Catholics, she is justifiably enshrined among the great figures of church history. For non-Catholics, she can be admired as a model of selfless benevolence whose spirit remains an invigorating presence behind numerous charitable organizations.

-

1

Yacovazzi’s book also contains some surprising errors. For example, Catharine Beecher appears throughout the book as “Catherine” Beecher. Norwood Damon becomes “Damon Norwood.” Edward Zane Carroll Judson is called “Judson Edward Zane Carroll,” and Lydia Maria Child appears as “Lydia Marie Child.” Yacovazzi identifies the author of Glimpses of New York correctly in the endnotes as William M. Bobo but wrongly as George Lippard in the text. The publisher of my book George Lippard is G. K. Hall, not “University of North Carolina,” and the 1988 edition of my Beneath the American Renaissance was published by Knopf, not Oxford University Press, which brought out the 2011 edition. ↩

-

2

Redwood. A Tale (1824; George P. Putnam, 1950), p. xv. ↩

-

3

Diary of Archbishop Martin J. Spalding, January 1, 1863, in Kenneth J. Zanca, “Baltimore’s Catholics and the Funeral of Abraham Lincoln,” Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. 98, No. 1 (2003), p. 94. ↩