“Political language,” George Orwell said, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” He might have added that literary language is often used for the same purpose. The verbally prodigious English writer John Lanchester is a case in point. His characters, Lanchester has said, are people “who can’t quite bring themselves to tell the truth about their own lives.” This is putting it mildly. Tarquin Winot, the gastronome-sociopath narrator of Lanchester’s very funny debut, The Debt to Pleasure (1996), will stop at nothing to prove that he and not his older brother, a world-famous conceptual artist, is the true genius in the family. The novel, whose principal debt is to Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, is written in the form of a food memoir, but the cracks in Winot’s psyche soon become visible beneath the surface of his opulent culinary sentences:

Bear in mind that the practice of “deveining” prawns—breaking open their backs with a surgical forefinger or a knife, and stripping out the dark thread of the alimentary canal—is necessary only in the tropical climates where food “goes off” quickly (like people, or like a linen suit on a muggy afternoon), though there it is very necessary indeed, unless it is your specific intention to poison somebody.

Winot follows Thomas De Quincey in considering murder as one of the fine arts—in fact, he goes beyond mere consideration—and you can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style.

Reality-denial, and the mental and verbal habits to which it gives rise, are also prominent in Lanchester’s second novel, Mr. Phillips (2000), the story of a day in the life of a middle-aged accountant who’s just been fired but has yet to tell his family. The Monday morning after the Friday he gets canned, Mr. Phillips (as Lanchester refers to him, with a kind of fond estrangement, throughout) sets off from his South London home dressed in his work clothes and carrying his briefcase. He has nowhere to go but much to evade (not just his redundancy but a dormant marriage, a pair of baffling, distant sons, and a deep archive of stalled ambitions), and so the novel, like Ulysses, whose influence it unanxiously welcomes, becomes a map of its protagonist’s mental landscape as well as of the actual cityscape he traverses.

A compulsive doer of sums who as a trainee accountant fell in love with the double-entry bookkeeping system (“It seemed suddenly a whole new language in which to describe the world; or rather it suddenly seemed as if the world was describable in a new and better way”), Mr. Phillips fends off his disappointments by calculating the assets and liabilities of everything from a metropolitan park to his favorite football team. Lanchester wrings plenty of comedy and pathos from this preoccupation, but he never makes it seem small-minded or materialistic. He respects his accountant’s respect for money because (as another Lanchester character says) money doesn’t lie, however much people may lie about it.

Lanchester’s grounding in the psychology of lying has stood him in good stead in his second career as a financial journalist. While doing research for his fourth novel, Capital (2012), a social panorama about the intersecting lives of the residents of a single South London street in the year before the 2008 financial crisis, he “stumbled across the most interesting story” he’d ever found. This was the one, he writes at the start of his outstanding nonfiction book I.O.U. (2010), about how “a huge, unregulated boom in which almost all the upside went directly into private hands” was “followed by a gigantic bust in which the losses were socialized.” It is also, like one of Lanchester’s novels, a story about a character with a constitutional predisposition against telling the truth—i.e., the modern banker—who concocts a new language (the intentionally opaque financial jargon of derivatives, credit default swaps, and securitization) in order to conceal his darker purpose and keep reality at bay.

Such a CV would seem to make Lanchester just the man for the job of writing the Great Climate Change Novel, or at least a distinguished addition to the genre. For what is climate change if not the biggest subject about which human beings can’t quite bring themselves to tell the truth? And what is “climate change” (that is, the phrase itself) if not a glaring euphemism, a bland, palliative designation for a series of catastrophes that, barring radical human intervention, may very soon begin to upend the social order, opening the floodgates to death and suffering on an unprecedented scale?

The Wall, Lanchester’s new book, has these concerns clearly in its sights. In a day-after-tomorrow future, what’s referred to simply as the Change has brought about environmental and social collapse. To protect itself from rising sea levels and to keep out the multitude of climate refugees from around the world, known simply as Others, desperate to get in, an island nation that bears a strong resemblance to the UK has built a five-meter-high concrete wall around its ravaged coastline. Maintaining the Wall has required the government to introduce mandatory national service: every citizen must spend a two-year tour of duty standing guard atop the ramparts.

Advertisement

We meet our narrator, Joseph Kavanaugh, a conventional, rule-abiding young man, on his first day as a Defender (as those serving on the Wall are called). He isn’t looking forward to it. On top of the cold, the awful food, and the grueling twelve-hour shifts, there is the prospect of being assaulted at any moment by a flotilla of Others whose tactics, we learn, have been growing ever more sophisticated (and attacks ever more frequent). The Defenders’ orders are unambiguous: shoot to kill.

Like the unnamed magistrate at the start of J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, Kavanaugh, when we first encounter him, is in a state of moral arrest. He doesn’t go about the business of shooting refugees with any particular relish, but neither does he have the makings of a conscientious objector. What he wants more than anything, besides getting through his time on the Wall unscathed, is to claw his way up the social ladder, to a position where he might enjoy the comfort and security that are now the preserve of a narrow elite. It is hard to fault him for his cynicism. As a member of the first post-Change generation, he harbors a fierce resentment toward his parents and their contemporaries—those who “irretrievably fucked up the world, then allowed us to be born into it.”

One of the novel’s most suggestive episodes concerns Kavanaugh’s first trip home on leave. Parent–child relations, strained at the best of times, have deteriorated to the point of ruin. Kavanaugh and his mother and father can barely exchange an amicable word. “The thing about Dad,” he tells us ruefully, “is he still has the emotional reflexes of a parent. He wants to be in charge, to know better, to put me straight, to tell me about back in the day, to start sentences with the words ‘When I was…’” Kavanaugh is having none of it: “I don’t want to know their advice or to know what they think about anything, ever.”

Understandably, people of Kavanaugh’s generation aren’t exactly keen to have kids of their own. As their faith in the future has dwindled, so has their willingness to bring new life into the world. “We can’t feed and look after all the humans there already are,” Kavanaugh says, summing up the general mood, “so how dare we make more of them?” Fewer babies might sound like just the thing on an overheating, resource-starved planet, but the ironies entrained by the Change are cruel, and constantly proliferating. Because the Wall, at more than six thousand miles long, needs so many Defenders to maintain it, society needs to stop the birthrate from declining. As an incentive, those who procreate are excused from Wall duty. After Kavanaugh gets together with Hifa, a taciturn but physically courageous fellow Defender (theirs is a workplace of strict gender parity), this is the route they decide to take, though not before surviving a surprise attack that leaves a number of their comrades dead. They are trying to conceive when another horrifying turn of events causes their plans to unravel.

The Wall is a powerful thought experiment. Like the crusading vegetarian at the dinner party who asks his carnivorous hosts whether they’d personally be willing to hunt, kill, and butcher the meat they consume, Lanchester is, in effect, asking those who live in the world’s developed countries whether they’d be prepared to participate in the cold-blooded murder of climate refugees that their comfortable lifestyles may one day necessitate. American citizens, in whose name refugees are currently being killed (by accident) and imprisoned (on purpose) at the southern border, already find themselves confronted with a variation on this question, as do Europeans whose governments have cruelly botched the migrant crisis. The future that Lanchester forecasts has, in a sense, already begun to arrive.

But a thought experiment is one thing, a novel quite another. Strangely for a storyteller of such poise and intelligence, Lanchester often seems unclear about exactly what kind of book he is writing. Is it a spare dystopian fable, in the manner of Orwell’s Animal Farm or Angela Carter’s Heroes and Villains, or a work of full-fledged realism with a futuristic (or alternate-present) setting, like Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go or Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale? In interviews, Lanchester has said that The Wall came more quickly than his other novels, and this is certainly how it reads. There is, on the one hand, a palpable excitement at having hit upon a scenario that so potently distills the existential threat facing humanity. This excitement is clearest in the passages of straightforward exposition, where Lanchester is simply laying out the rules of his fictional world (and providing answers to the morbid question that we naturally bring to stories about civilizational collapse: How bad will things get?). Consider this draconian stipulation:

Advertisement

For every Other who got over the Wall, one Defender is put out to sea. A tribunal of our fellow Defenders convenes that same day and decides who was most responsible, and those people, in that order of responsibility, would be put in a boat that same day. If five Others got over the Wall, five of us would be put to sea. It was easy to imagine being those people. Your old comrades pointing guns at you while you pushed your boat out into the water, the only feeling colder and lonelier and more final than being on the Wall.

On the other hand, Lanchester appears to be of two minds about how much reality he ought to bestow on this fictional world, as though a surfeit of descriptive detail might smother the mythic force of his conceit. It is an understandable dilemma: a chapter on Napoleon’s unhappy piglethood or a recurring motif involving Boxer’s dream life obviously wouldn’t do anything to enhance the power of Animal Farm (quite the opposite). The problem is that Lanchester never makes a decision. He is unwilling either to pare his book down into something more haunting and elliptical or to work it up into a narrative of convincing heft and complexity. The result is a sappy humanism conveyed in pale, prefab prose. This, for example, is how he describes Hifa’s childhood:

The dad who was great when he was there but was prone to go away without warning, until one day he never came back; the charismatic, flaky, loving, difficult mother. The small-life country childhood which makes you need to get away so badly you can feel it in the roots of your hair.

Poor Hifa (perhaps the second-most-important character in the book) is doubly neglected, by both her parents and her creator. Her relationship with Kavanaugh is supposed to provide the book’s emotional fulcrum (our investment in the narrative has much to do with whether or not the couple will make it), but it is hard to care about someone furnished with such an off-the-rack personal history. Lanchester seems to regard her the way a campaigning politician would a potential voter, as someone to be greeted, chatted up, and dispatched as quickly as possible.

The book is rife with signs of haste. There are the sentimental clichés used to describe relics of the pre-Change world. An oil lamp is “an ordinary miracle” and the light it gives “the most beautiful thing” that Kavanaugh “had ever seen.” There are the clauses of redundant amplification with which Lanchester optimistically stuffs his sentences: “But as we left it behind and it moved into the past, moved into the category of experiences which were over, I realized I felt a sense of loss.” “I felt he was really seeing me, connecting with the reality of my presence in front of him, for the first time.” There are, above all, the passages of tacked-on emotional commentary, often an indication of a guilty authorial conscience, a tacit acknowledgment that not enough has been done with the material to let it speak for itself: “Loss, loss, there was just so much loss, in what had happened to us,…in what we had done to the world, in what we had done to each other and in what was happening to us.”

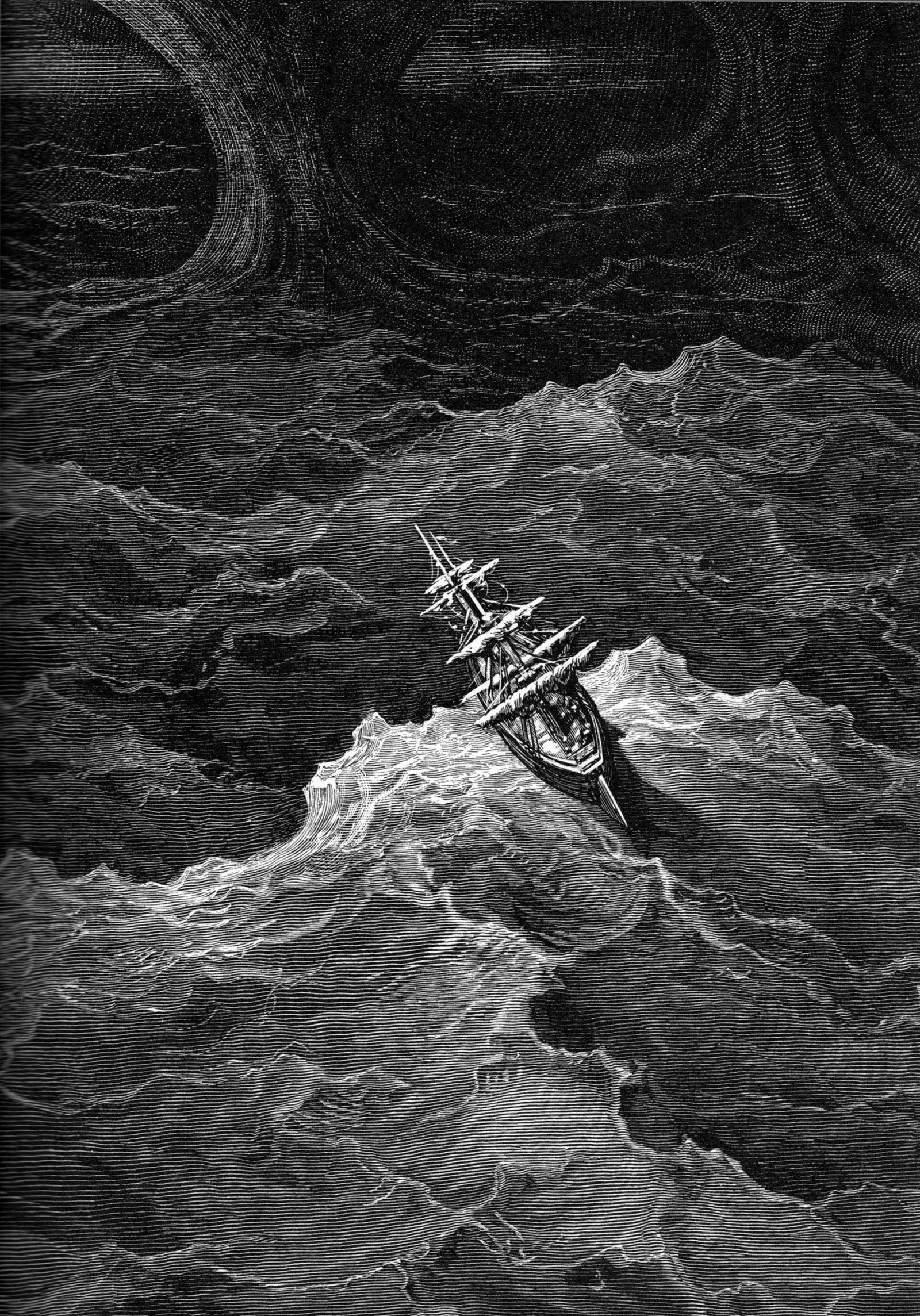

As the reader realizes will happen from the moment the one-in-one-out rule is mentioned early in the book, Kavanaugh is eventually cast adrift, along with Hifa and a few more supporting characters, after several Others make it over the Wall in an especially brutal onslaught. Buffeted by the ocean currents in their inflatable dinghy, our newly otherized heroes seem destined for a watery grave. It is here, in the novel’s final third, that Lanchester’s writing is at its most formulaic. Again and again, all seems lost, only for some deus ex machina to pop up and save the day. On the brink of starvation, Kavanaugh and crew catch sight of land—a few cliffs jutting from the sea where a makeshift fishing community, their boats moored to the rocks, is managing to eke out an existence. The former Defenders are welcomed into the fold, and Kavanaugh experiences a belated moral awakening, rendered in TV-voice-over prose: “If I was an Other and they were Others perhaps none of us were Others but instead we were a new Us.”

Until recently, these cliffs had been the highest point on a presumably habitable island. One day Kavanaugh finds himself musing on “what it had once been like—beaches, gentle slopes, maybe a few houses down near the water. In living memory the seafloor below us was dry land. All drowned now. Part of the old drowned world.” Kavanaugh may be unaware of it, but the author of the book he is narrating is dutifully name-checking J.G. Ballard’s novel The Drowned World, which inaugurated the climate fiction, or cli-fi, genre back in 1962, when anthropogenic climate change had yet to be widely accepted by the scientific community. In Ballard’s story, set in the year 2145, it is not man-made carbon emissions but “a series of violent and prolonged solar storms” that have caused global temperatures to rise, the ice caps to melt, and the sea to engulf the age-old centers of human civilization.

Unlike the world of The Wall, then, collective guilt and resentment are not salient emotions in this projected future, in which humanity has retreated to the polar regions. Still, what makes the book so memorable and absorbing is not just Ballard’s ravishing visual evocation of land- and seascape (“the streets and shops” of London, sixty feet beneath the surface of the water, “preserved almost intact, like a reflection in a lake that has somehow lost its original”) but the imaginative energy he invests in the question of how human beings might change along with the climate. Dr. Robert Kerans, a marine biologist, is part of a waterborne mission to study the flora and fauna of the tropical lagoons that now cover Western Europe. He and his colleagues have been observing a kind of reverse evolution as the continent is overtaken by dense jungles and giant lizards. Kerans, who has grown increasingly remote and subject to nightmares of unusual intensity, thinks he notices an equivalent process in himself and those around him—“the slackening metabolism and biological withdrawal of all animal forms about to undergo a major metamorphosis.” The hunch is fully articulated by his friend and confidant Dr. Bodkin:

Just as psychoanalysis reconstructs the original traumatic situation in order to release the repressed material, so we are now being plunged back into the archaeopsychic past, uncovering the ancient taboos and drives that have been dormant for epochs. The brief span of an individual life is misleading. Each one of us is as old as the entire biological kingdom, and our bloodstreams are tributaries of the great sea of its total memory.

Motive, psychology, and coherent selfhood, staples of the novelistic tradition, all come under thrilling scrutiny in The Drowned World. The human subject faces no such destabilization in The Wall. Lanchester, so fruitfully receptive to the example of Nabokov in his first novel and Joyce in his second, might have taken a few more hints from his cli-fi precursor.

Lanchester’s evolution as a novelist has itself been fitful and nonlinear. After the brazen originality of The Debt to Pleasure and Mr. Phillips, he came up with something truly unexpected: a conventional blockbuster. Fragrant Harbor (2002) is a multigenerational epic set in Hong Kong, where Lanchester, the son of an Irish former nun and a South African banker, spent much of his childhood. Encompassing a broad cast of characters and a checklist of historical events, including the brutal Japanese occupation, the novel is accomplished but less fun to read than its predecessors. There is a slightly dispiriting air of conscientiousness about the whole project.

Something similar is true of Capital, a considerable feat of sustained imaginative sympathy—along with a host of white natives, the dramatis personae includes a Senegalese soccer player, a Polish builder, a Zimbabwean traffic warden, a Hungarian au pair, and a British-Pakistani family that owns the corner shop—whose breadth ends up seeming labored and overwrought. For all its variety and exuberance, the book is essentially schematic: the rich, white characters are reckless and lazy, while the struggling immigrant ones are savvy and industrious.

Lanchester may be on to something here, but a novel that merely confirms its readers’ progressive social values, however imperative they may be in a time of grotesque inequality and recrudescent chauvinism, is going to test the patience of all but the most ideologically immaculate. In 2015 Capital was turned into a three-part BBC miniseries, which actually seemed to be the ideal medium for the story Lanchester wanted to tell. The novel, at 528 pages, gives us more exposure to its flat, cartoonish characters than we really need; on TV, it all goes by much more quickly. The brilliant acting also helped, as did the screenwriter Peter Bowker’s decision to whittle down the number of characters and subplots.

Sadly, The Wall extends this run of well-meaning but ultimately disappointing fictions. You can’t argue with the urgency of Lanchester’s climate politics, but his novel is morally overlit, never leaving the reader in any doubt as to how she ought to feel about its characters and conflicts. The people who “irretrievably fucked up the world” and now implement vicious policies to stave off total anarchy are the bad guys, while those left to live in it—the ones who feel “loss, loss…so much loss”—are the victims, though some are more victimized than others.

Lanchester is far from the only contemporary writer to run aground on these moral simplicities. “Literature is the human activity that takes the fullest and most precise account of variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty,” Lionel Trilling said. But variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty can begin to look like mere literary fetishes in an age when financiers enrich themselves while wrecking the global economy, fossil fuel companies retard indispensable climate action, and governments composed of racist demagogues and corporate shills do all they can to aid and abet the plunder. How to take account of this unsubtle reality without succumbing to pantomime or agitprop is a question on which the immediate future of the social novel depends. Few writers seem better equipped to reckon with it than the immensely talented and minutely informed Lanchester, who may yet come up with a satisfying fictional answer. Meanwhile, as the planet warms and the waters rise, The Wall should make a great miniseries.