When Joshua Sperling’s biography of John Berger arrived at my door, I approached it with trepidation. I’d known Berger for more than forty years, and biographers, having amassed reams of information about a life, may render it in ways that make it unrecognizable to friends or family. Upon his death in January 2017, many of Berger’s British obituarists, on both the right and the left, engaged in settling decades-old political or art world scores. Berger had not only escaped the confines of his British island but he had had the audacity to rise to fame before doing so. From his French mountainside he denounced injustices that were everywhere visible, even in his native land. He was read in a multiplicity of languages. None of this could altogether be forgiven.

Berger was already famous, even notorious, when I met him in the mid-1970s. In 1972, at the age of forty-five, he had won the Booker Prize for his novel G., in which Don Giovanni and Garibaldi, sexual and political emancipation, coincide. Taking aim at the then funders of the Booker—Caribbean sugar plantation grandees for over a century—Berger gave half his prize money to Britain’s Black Panthers. The other half he used to write his prescient book on migrant labor, A Seventh Man (1975), an investigation—combining documentary, imaginative witnessing, statistics, poetry, philosophy, and photography—into the lives of the millions displaced by global forces over which they have no control.

Berger was also well known as the trenchant and controversial art critic of the New Statesman and New Society. Through his groundbreaking 1972 BBC series Ways of Seeing, he had become a television star. With his flowery open-necked shirt, his cigarettes and direct gaze, Berger provided British society with a counterweight to the aristocratic connoisseur Kenneth Clark and his BBC series Civilisation. Ways of Seeing altered how many people think of images in everyday life and explained to the public the way in which oil painting became a means of transforming the visible world (including women) into property. As Berger wrote in the accompanying best-selling book:

Oil painting did to appearances what capital did to social relations. It reduced everything to the equality of objects. Everything became exchangeable because everything became a commodity. All reality was mechanically measured by its materiality. The soul, thanks to the Cartesian system, was saved in a category apart. A painting could speak to the soul—by way of what it referred to, but never by the way it envisaged. Oil painting conveyed a vision of total exteriority….

We are arguing that if one studies the culture of the European oil painting as a whole, and if one leaves aside its own claims for itself, its model is not so much a framed window open on to the world as a safe let into the wall, a safe in which the visible has been deposited.

Ways of Seeing brimmed with insights about art and society, about women and “the male gaze” (a phrase that Berger coined), about how advertising imagery functions and what it means, and much more.

In retrospect, the “more” had to do with seeing intellectual passion on the small screen. The “more” also included the first television sequence in which five highly vocal women and a single man debated how women are seen. Subversive, a man of the old then the new left, Berger was prepared to be something of a feminist. Ways of Seeing shares various formulations with G. “Men dream of women. Women dream of themselves being dreamt of,” he posits, setting down the logic of the male gaze that women internalize, so that we become our own objects. Like so much of what Berger wrote, his pithy expression of a condition launched a challenge to change.

I started off as Berger’s editor at Writers and Readers, the publishing cooperative we and a few others had founded in 1974. Mostly he didn’t need an editor, not on the many books we were reissuing, such as his now classic novel of a refugee artist, A Painter of Our Time (1958), from which Sperling takes his title; or on A Fortunate Man (1967), with the photographer Jean Mohr, his exceptional portrait of a country doctor who is the recordkeeper of the tragedies and miracles of a remote and impoverished rural community; or even on Pig Earth (1979), the first of his Into Their Labours trilogy—haunting fictions based on the lives of the disappearing peasantry of France’s Haute Savoie. As the years passed, we often read each other’s work and became occasional cotranslators, plotters of shows and events, and more importantly firm friends—the kind who can withstand the flare-ups of political disagreements and laugh about them later.

There was a visceral charge in his listening and his stance. And oddly, there was an ever-present sense of the inarticulate, some deep well of not yet expressible or perhaps inexpressible experience. “Kraków,” the opening story in the excellent collection Landscapes, published just before he died, evokes this quality. It originally appeared in Berger’s book of memory and memoir, Here Is Where We Meet (2005):

Advertisement

I have never been in this square before and I know it by heart, or rather I know by heart the people who are selling things in it. Some of them have regular stalls with awnings to keep the sun off their goods. It is already hot, hot with the blurred, gnat heat of the Eastern European plains and forest. A foliage heat. A heat full of suggestions, that does not have the assurance of a Mediterranean heat. Here nothing is certain. The nearest thing to certainty here is a grandmother.

Some sixty works—fiction, essays, articles, poetry, plays, screenplays, inventive combinations of photography or drawing, or all of these—appeared in Berger’s lifetime. He could leap like few others from the politics of an inhuman economic order to the intimacy of experience. He paid no heed to the strictures that divide academic disciplines or conventional forms. For Berger, there is a “conviction that works of the imagination can be political just as the work of criticism can be imaginative, and that to furnish an historical lens on the past is also to re-focalize its light towards the future.”

Sperling’s biography, trenchant and written with panache, is structured with that imperative in mind. He only minimally addresses Berger’s personal life, and only insofar as it affected his work and his public positions. Given Berger’s longevity, productivity, and multiple collaborations, even this concentration on work and ideas could have resulted in a much longer book.

Berger was born in 1926 to a working-class suffragette mother and a father who had hoped to be an Anglican priest, but, after enlisting in 1914 at the outbreak of war and serving as a junior officer on the front line, instead went on to become a director at the Institute of Cost and Works Accountants (and eventually earned a royal honor for his public works, a detail that goes unmentioned by Sperling, perhaps because it carries less significance for him as an American than it might for a British biographer, who would note the fact, whether to stress or diminish its import). The war damaged him. Though he rarely spoke about it, “its indirect presence impressed itself” on John and his younger (not older as Sperling states) brother. Berger’s 1970 poem “Self Portrait 1914–1918” testifies to the impact of his father’s experience, and also his own arrival just after the defeat of the general strike of 1926:

I was born of the look of the dead

Swaddled in mustard gas

And fed in a dugout.

Curiously, we don’t learn from Sperling that Stanley Berger’s paternal family were Jews originally from Italy, perhaps not unlike Umberto, the father of G.; and that Stanley, a child of nonobservant parents, had converted to Anglo-Catholicism.

Sent to boarding school from the age of six, as children of the middle classes then often were, Berger took refuge from the school’s culture of bullying in literature and art. At the age of sixteen, before his finals, he ran away from St Edward’s in Oxford and took up a place at the Central School of Art in London. It was 1942 and bombs were raining down on the city. But this was Berger’s first taste of real independence and he relished it, as he did living with his first love, a fellow art student.

Two years later, at eighteen, he joined the army. As he saw it, bureaucratic revenge for his refusal to take up an officer’s post relegated him away from active combat to a training depot in Northern Ireland. But there he flourished: it was his first full encounter with the working class, some of whom were nearly illiterate. Berger became their scribe, writing down the stories they told him for their sweethearts at home—preparation for his later tales of peasant life in France. It was there, too, that his unwavering politics were shaped: throughout his life he spoke for the poor and the dispossessed.

Many of the British writers and artists of his generation who had formed part of the antifascist struggle were of the left and often sympathetic to Russia, a wartime ally. The cultural world of the 1950s and 1960s was shaped by antiestablishment “angry young men.” Some gradually inclined toward the right; others joined the Communist Party. Berger didn’t, though some assumed he had. As he made clear in a 1984 article in Marxism Today, if his “gut solidarity” was with those “without power, with the underprivileged,” he couldn’t, as a painter, critic, or writer, bring himself to sign on to the narrowly constricting and repressive Soviet views on art.

Advertisement

After the war Berger trained as a painter at the Chelsea School of Art and transformed himself into a sometime curator and a brilliantly incisive and increasingly provocative critic, first at the Tribune and then at the New Statesman. Berger championed an engaged realism, an art that lived on murals and in public spaces, rather than fetishizing artworks as snob commodities. He embraced Renato Guttuso, the Sicilian partisan and painter who portrayed crowds at public gatherings or markets in vibrant expressionist color. He derided the star of the art world cognoscenti, Francis Bacon, because of his willfully shocking, alienated world of screaming popes. Berger felt Bacon’s stage management of anguish allowed no space for reflection. In 1972, when Bacon’s fame had grown even greater and after a major exhibition of his work at the Grand Palais in Paris, Berger wrote, “It is not with Goya or the early Eisenstein that he should be compared, but with Walt Disney.” As Sperling rightly underlines, Berger’s “evaluations of his contemporaries were regularly wide of the mark,” but he was remarkably prescient in his criticism of “the system of art.” He had a “built-in, shockproof, bullshit detector,” something “Hemingway famously said a good writer needed.”

Sperling vividly conjures the cultural battles that grew hotter during the cold war between Berger, who believed in figuration and politically engaged art, and members of the British art establishment who wanted art untarnished by politics and championed the new formalism and Abstract Expressionism. By 1956, with both the Suez crisis and the Hungarian uprising, mounting tempers, and the arrival at the Tate of a major show from the US featuring Pollock, Rothko, and de Kooning, this antagonism peaked. In his “Exit and Credo,” published in the New Statesman on September 29 of that year, a troubled Berger declared that he was leaving the magazine and his often maligned role as its art critic:

Whenever I look at a work of art as a critic, I try—Ariadne-like for the path is by no means a straight one—to follow up the threads connecting it to the early Renaissance, Picasso, the Five Year plans of Asia, the man-eating hypocrisy and sentimentality of our establishment, and to an eventual Socialist revolution in this country. And if the aesthetes jump at this confession to say that it proves that I am a political propagandist, I am proud of it. But my heart and eye have remained those of a painter.

Sperling notes that if Berger “was caricatured as a propagandist…it was his enemies who were on the payroll” of the CIA, which would eventually be shown to have backed not only the Tate exhibition but also Encounter, the magazine that was the cultural voice of the anti-Communist liberals.

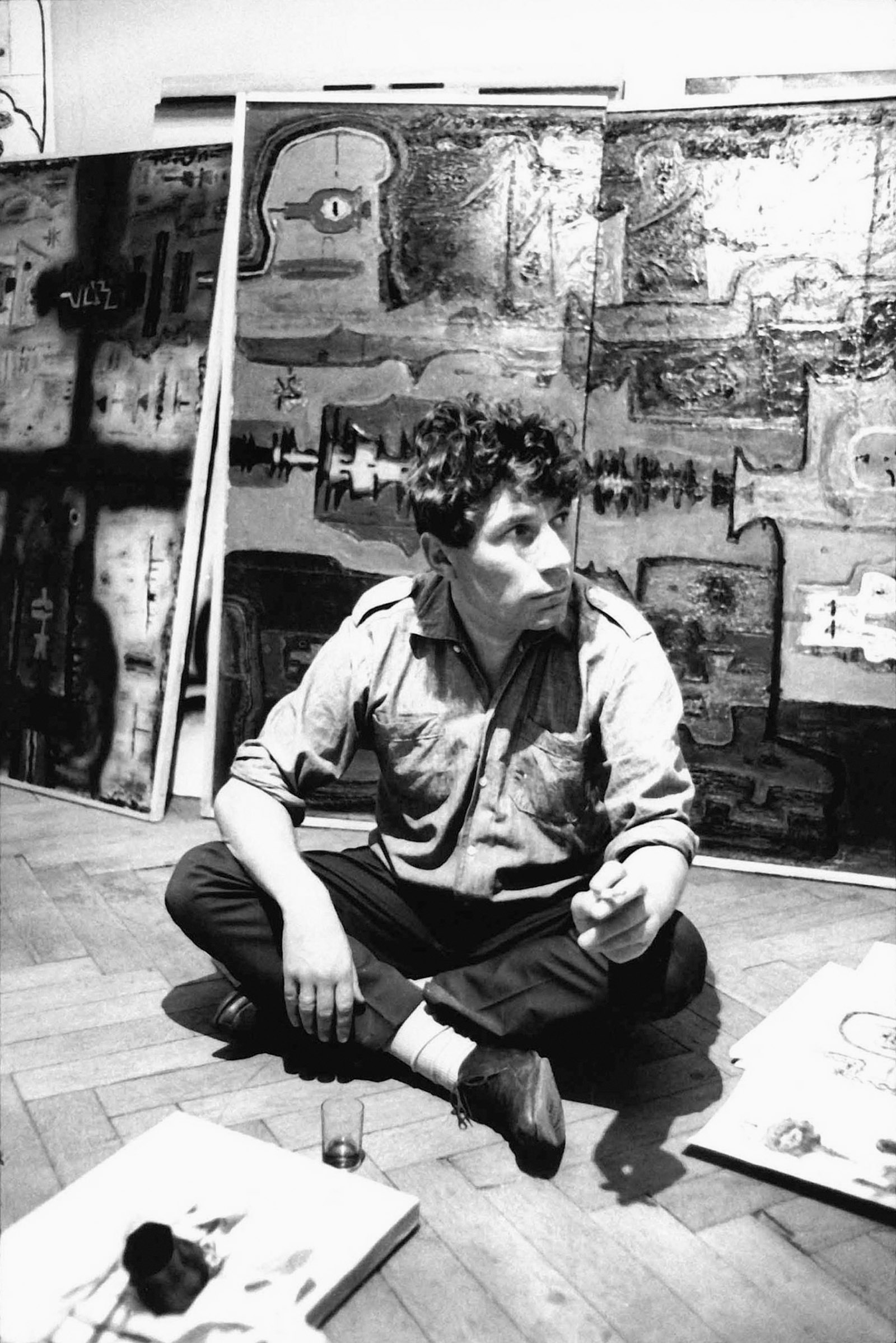

Berger’s first novel, A Painter of Our Time, takes up some of these tensions, while underlining his self-declared romantic belief in the mystery of art. In it he portrays the life and daily practice of a Hungarian refugee artist, Janos Lavin, who struggles both with his work and with exile. At the end of the book, on the verge of success and just after his first London show, Lavin abruptly abandons his studio, his upper-class wife, and Britain itself.

An exiled, apolitical London life and his own struggle to paint have grown meaningless for Lavin while young Hungarians protest. So he disappears into Hungary. No one in London knows what has happened to him, and the narrator wonders whether he fought “side by side with those workers’ councils who resisted the Red Army”—or did he oppose resistance and find himself lynched by a mob? “The full tragedy of the Hungarian situation is revealed by the fact that we, who have the advantage of knowing some of this man’s most intimate hopes, thoughts, confessions, cannot with any certainty declare which of these courses of action he was bound to follow.”

When the novel was published, Stephen Spender, then the editor of Encounter, called Berger’s hero, who plunges back into communism, a “killer” and “advocate of judicial murder.” In the heat of Spender’s cold warrior anticommunism, Berger reminded him of another ideologue, the young Joseph Goebbels. His review certainly helped to kill the book: it was remaindered shortly after publication.

Sperling rightly understands A Painter as an expression of Berger’s inner paradoxes, his intense struggle between the imperatives of political commitment and his understanding, rooted in practice, of the mysterious power and autonomy of art. Some of Sperling’s most incisive commentary comes in the discussion of this first novel: “Never before had a novel captured so forthrightly the phenomenology of sustained creative labour: the fragile yet compulsive nature of routine, the hour-to-hour exhaustion and exhilaration, the way one’s every concern can suddenly condense around the details of a brushstroke or passage.”

In 1961 Berger left Britain for life on the Continent. He often returned to earn money by working in British journalism or arts television, but home became first Geneva, where he followed the translator Anya Bostock, an émigré from Vienna and a prominent early collaborator in his work, as well as the woman who would become the mother of his first two children. After some peripatetic years in Provence, he settled in a village nestled beneath Mont Blanc in the Haute Savoie with Beverly Bancroft, an American whom he had met at his sometime publisher, Penguin. Eventually there was another base on the outskirts of Paris with the Ukrainian-born novelist Nella Bielski.

Sperling doesn’t pry into Berger’s love life, which in its early manifestations was not altogether unlike that of his Don Juanesque hero G. One could say that Berger’s feminism grew out of his passions as well as his Marxism, and an accompanying attempt to understand or put himself in the place of the women in his life. His later relations, even if nonmonogamous, were long-lasting and loyal.

Sperling is good on Berger’s critical influences, on his struggle with Marxist aesthetics, and his controversial Success and Failure of Picasso (1965). He sees this book as Berger’s attempt to rethink modern art as a whole. Berger is critical of Picasso: he condemns the “placelessness” of pure abstraction and counters this with an enthusiasm for the moment of Cubism, seeing in it the apogee of Modernism, in which the whole “promise of the modern world” resides. Sperling probes Berger’s understanding of Cubism. It is not for Berger the “parent of painterly abstraction.” Instead it is “the orphaned child of revolutionary dreams” that came into being with the turn of the century’s “new urban sensorium” and encompasses everything from “the invention of the automobile, the aeroplane and cinema” to relativity, quantum mechanics, the consolidation of monopoly capital, the birth of modern sociology and psychology, and the rise of a confident Socialist International.

G. was Berger’s attempt to write a fiction with a “cubist” structure. Metafictional interventions, montage, and a doubled-up time frame bring to life a hero who is at once a seducer, a liberator, and a child of the Modernist epoch—although, since the book was written during the late 1960s, its revolutionary dreams are predominantly and vividly sexual. Berger, like his contemporaries, thought that writing openly about sex had social value. Sperling, who is of a much younger generation, is not altogether sure of this, but Berger brilliantly—and it seemed in the early 1970s dangerously—turned his analytical eye to desire, arousing controversy in the process. Sperling quotes some of the outraged headlines in the press: “Intellectualized porn,” “Porn with graffiti.”

In a telling moment during a conversation between Berger and the novelist Michael Ondaatje filmed for the Lannan Foundation in 2002, Ondaatje asks whether Berger locates his main influence in painting or writing. Berger reflects for a long moment and then says, “the cinema.” Ondaatje asks why, and Berger replies:

Cinematographic editing, by the fact of the possibility of long vistas and close ups one after the other…and lastly because of the relationship of the cinema to its public. It’s an image of collaboration—of the spectator who is no longer a spectator but is part of the penning of the story.

Berger finds this more encouraging than the isolation of painting or writing.

Sperling rightly focuses on Berger’s inventive 1960s collaborations with Jean Mohr, which resulted in those masterpieces of witnessing, A Fortunate Man (1967) and A Seventh Man (1975), books that move from long shots to close-ups, from narrative to editorial interjections, with Berger playing the part of an auteur director. Sperling approves less of a later collaborative volume, Another Way of Telling (1982), which is at once about photography and the men and women from the valley community where Berger lived and whose stories he told. Sperling thinks it fails to exemplify the “mutually fructifying tension” between text and image, with a resulting “abdication of the verbal to the visual.”

But by 1982 Berger had already not only written G. and engaged in the TV collaboration of Ways of Seeing but had also become screenwriter and ideas man to the Swiss film director Alain Tanner. Few literary or art critics have paused to include this work in the Berger canon, and it’s very good that Sperling, who studied and writes on film and media, has done so. La Salamandre, Le Milieu du Monde, and Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000, all made with Tanner, tangle with the lives of the 1968 generation. The films are marked by a youthful je m’en foutisme and, in Jonah, by a failed attempt at collectivity. Play Me Something, the film Berger made with the Scottish director Timothy Neat in 1989, oddly doesn’t feature in this account of collective endeavors: Berger, as well as being the film’s cowriter, stars in it as an expansive storyteller who arrives on the Scottish island of Barra and tells a mesmerizing tale about a peasant who goes to Venice.

One of Sperling’s best chapters, entitled “Beyond Ideology,” engages with Berger’s “post-structuralist nausea,” his ultimate rejection of the late-1960s and 1970s left for its fashionable theoretical entrapment in an Althusserian ideology that prioritized systems, the state, and the institutions of capitalism over people and their potential. Berger favored a profound humanism in which hope is made possible through work, whether physical, aesthetic, or intellectual. “As soon as one is engaged in a productive process,” he wrote in an essay on Leopardi, “total pessimism becomes improbable. This has nothing to do with the dignity of labour or any other such crap; it has to do with the nature of physical and psychic human energy…. Work, because it is productive, produces in man a productive hope.”

Ultimately Berger’s most adventurous collaboration, though some thought it romantically quixotic, was with the peasantry of the Haute Savoie. It involved a great deal of work, both physical and creative. He became his alpine village’s storyteller, and like the old peasant he designates as his fellow “storyteller” in the 1984 article bearing that name and collected in Landscapes, he was fascinated by “the typology of human characters in all their variations, and the common destiny of birth and death, shared by all.” Unlike the peasant storyteller’s world, Berger’s had no center, no village he was tied to by birth. Ever more at home with mystery, he began to give precise description to a range of unusual encounters—with the homeless in King (1999), a book narrated by a dog in which the author’s name does not figure on the cover: with the dying in To the Wedding (1995); and with the dead in Here Is Where We Meet (2005), one of his finest collections.

This last belongs to what Sperling aptly calls Berger’s “late lyrical flowering.” So, too, does Bento’s Sketchbook (2011), Berger’s “conversation” with Spinoza, a lens grinder by trade, ostracized by his Dutch Sephardic community for his radical questioning of a providential God. In his last decade Berger drew more and more, and the act of seeing, ever important to him both physically and metaphorically, increasingly called out for a lens grinder.

Why Spinoza, as Berger moved into his eighties? In an interview with The Paris Review, Berger said he had long been fascinated by the philosopher:

If one wants to be very simple about it I suppose that fascination, or that secret, has to do with his rejection of the Cartesian division between the physical and the spiritual, between body and soul. Because Spinoza maintained that the two are indivisible and that the body is not a kind of machine, as Descartes suggested.

Sperling is eloquent as he describes the tragic nature of Berger’s vision toward the end of his life. He may not always have been right, but “Berger taught us that it is possible neither to channel the complexities of experience into the sureties of ideology nor to seek refuge under an art-for-art’s-sake canopy of culture.” To his fierce denunciation of the destructions wrought by our civilization during the last century, Berger added what constituted “ethicide”: “The blunting of the senses; the hollowing out of language; the erasure of connection with the past, the dead, place, the land, the soil; possibly, too, the erasure even of certain emotions, whether pity, compassion, consoling, mourning or hoping.” If Berger’s ultimate vision is bleak, his way of seeing, together with the very power of his prose, its immediacy and lyricism, has leapt across the years to give hope to new and younger generations, as this biography itself exemplifies.

This Issue

May 9, 2019

‘A Painter Not Human’

Tintoretto’s Wildness