The Frick has chosen a somewhat wrongheaded way of presenting the sixteenth-century Italian painter Giovanni Battista Moroni. The exhibition’s subtitle is “The Riches of Renaissance Portraiture,” which can be taken in two ways. The irrefutable meaning is that Moroni significantly added to the body of portraits that we have from the Renaissance. The second, and debatable, meaning of “riches” is that the artist’s pictures give a tour of the era’s taste for finery. The curators probably believe that Moroni, whose work is being given its long-overdue first museum show in New York, illustrates both meanings of the word.

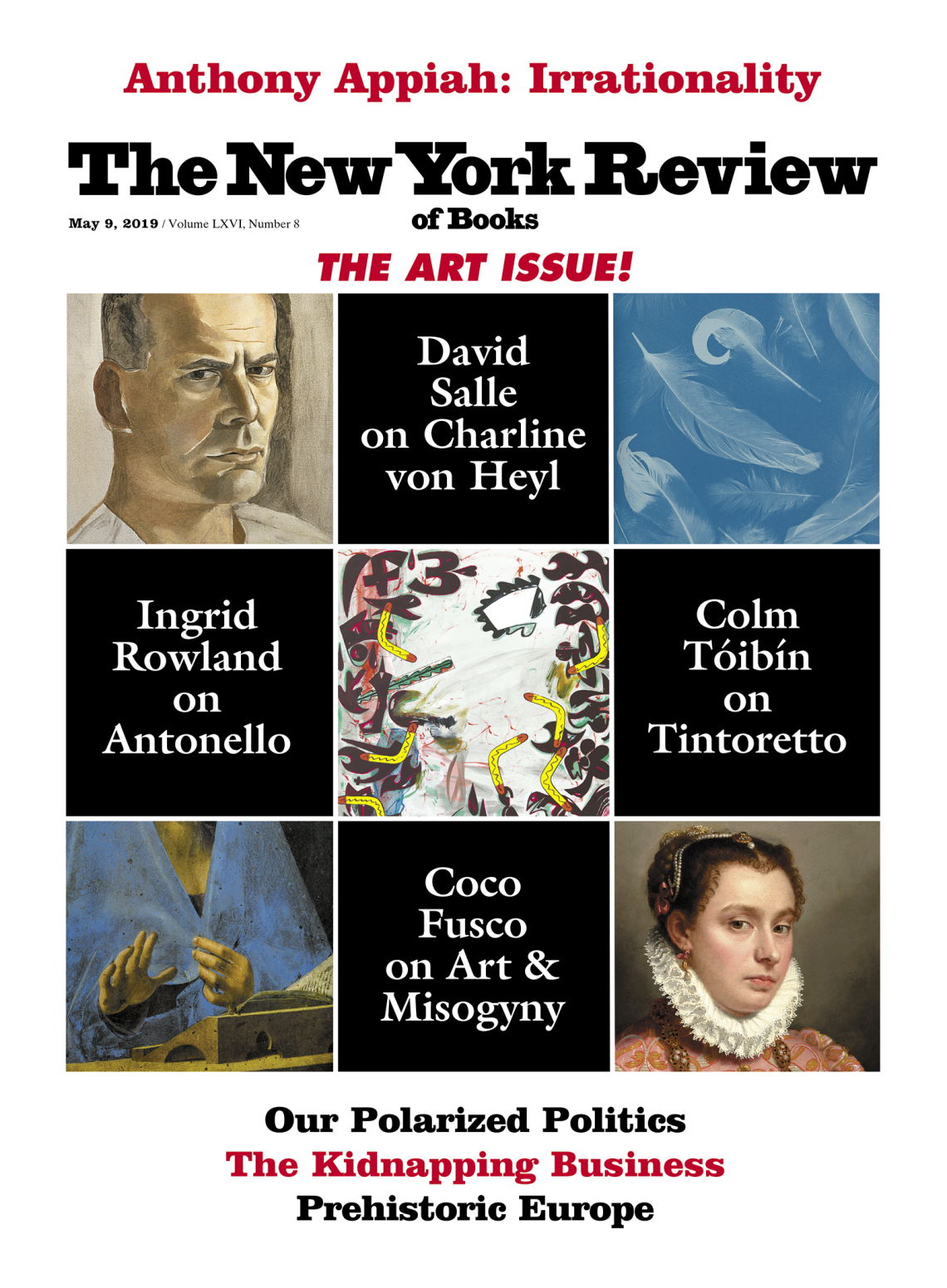

Material sumptuousness greets us right from the cover of the show’s catalog. It presents Moroni’s portrait of Isotta Brembati, a seated, amply built blonde who has a guarded look and who gives us plenty of finery to take in. She wears an impressive dark-green-and-gold brocaded gown and holds a white-and-pink fan, which might be made out of fur and has a gold handle. She has jewelry on her wrists, ears, neck, and hair, and after a second or two one discovers a bolt of fur around her neck. It is that of a marten, a weasel-like creature whose head in this adornment is made out of gold and precious stones. Should you miss this accessory and happen to turn over the catalog, you will find, along with a period quote about Moroni, a startling close-up photo of such a marten’s head. Composed of gold, rubies, garnets, and pearls, with teeth made of white enamel and special attention accorded the animal’s ears and eyebrows, this piece of jewelry demands a look.

The marten’s head dates from the same period as the painting and is in the exhibition. But the museum has not stopped with this ornament. If a sitter wears a rapier, such a rapier is in the gallery. If one sitter has shears in his hand and another holds an antique marble sculpture, these objects (though not the very ones in the paintings) are in the show. There are displays of a book of devotions, a fan handle like the one Isotta holds, woodcuts of the time illustrating the patterns on a sitter’s collar, and so on. Bizarrely, each of these items gets its own entry in the catalog. This dilutes the paintings: they become simply additional documents of a bygone time.

But the real problem with emphasizing the objects in Moroni’s pictures is that it runs counter to why we are drawn to the painter in the first place. Yes, he recorded the clothes of his sitters with great care, and the clothes of the time can be dazzling. He was a meticulous observer. Yet Moroni stands out in the Italian art of the 1500s not only because no other painter concentrated as fully on portraiture, but because he went about it in a particularly pure and straightforward way.

In his portraits of men and his fewer examples of women and children, it is the face of the person before him that is his one real, constant subject. He apparently didn’t make preparatory drawings. He painted with his sitter directly in front of him, often making that person’s head life-size on the canvas. He clearly loved painting skin and the different aspects of a face, and while we learn in the catalog that he applied paint thinly, one of the great pleasures of his pictures is the way he makes oil paint feel like a tangible, softly glowing, and somehow very clean substance. He is the least glossy of painters.

Moroni was hardly a protean creator on the order of such artists of his time as Titian, Tintoretto, or Veronese. When he wasn’t making portraits, he took commissions for altarpieces, and these appear, at least in reproduction, to be staid and impersonal. Nor do all his portraits catch fire. There are certainly canvases in the Frick’s show in which a sense of the sitter’s animating life is missing, and we see merely a face. Yet in the score or more of his finest examples (out of a total of something over a hundred) we look at sitters who radiate a consciousness. Without being stamped with one clear-cut attitude or mood, they have what one writer has called “truth of character.” Equally objective and empathic, working as if he were partly a photographer and partly a psychologist, Moroni could capture in each of his subjects what a viewer believes is that person’s fundamental self.

Not a lot is known about him. He left no writings, and while the catalog indicates, in a compact listing of every extant fact concerning him, when some of his pictures were dated and when he married (and that he had four children), there are no documents about his dealings with his sitters. We do not have the slightest sense of what he was like as a person.

Advertisement

In a roughly thirty-year career, spanning the 1550s through the 1570s, Moroni worked early on in Bergamo, in northern Italy, where his patrons, like the hesitant Isotta, were often wealthy aristocrats. By the mid-1550s or so, he was back in the smaller, nearby Albino, in the foothills of the Alps, where he had been born, though we do not know in what year, and where he died in 1579 or 1580. He was then probably in his late fifties. In Albino his subjects appear to have been largely professional people—professors, doctors, writers—who dressed more soberly than the people who sat for him in Bergamo. The altarpiece commissions he took on were often for rather out-of-the-way churches in the region.

He rarely painted more than one person at a time, and his goal apparently was to show a particular moment. It is usually when his sitter, seen in a uniformly clear light, is seated and looking directly at us or has turned a second before to look at us now. That is the case with Bust Portrait of a Young Man with an Inscription (circa 1560), one of the show’s standouts, in which a nameless, red-bearded, small-shouldered, vaguely damp, unglamorous, yet quietly prepossessing fellow wearing his collar up has turned to us and is taking our measure. In a sense, the painting is only a reprise of close-up portraits of a person looking out at us that had been done a hundred or more years earlier, in the brilliant beginnings of oil painting, by Jan van Eyck, Antonello da Messina, and others, except that Moroni has done it with a convincing, and modern, degree of flesh and volume. No painter coming after him, right up through the late Lucian Freud, has really superseded Moroni pictures such as Bust Portrait of a Young Man as a display of realism.

Sometimes his sitters don’t quite look in our direction. This happens in Portrait of a Young Woman (circa 1575), another high point, in which a thought perhaps has made the charming, seemingly quick-witted, and richly attired person (who reminds at least one viewer of Emma Thompson) glance away. Regardless of where Moroni’s subject is looking, her or his eyesight is felt. One half-believes that few painters of any era made eyes that to the same degree actually appear to be seeing something.

The painter’s quest was not, however, to capture instantaneity in itself. We don’t wonder what our young woman will turn to next. Nor does Moroni, for all that he can paint clothing, jewelry, or swords with precision, convey a sense of the larger world of his sitters. The settings of his scenes are designed to have as little impact as possible. As in his portraits of the unnamed young man and woman, the background might be simply a single grayish tone. Or it might be a gray-white wall that suggests some part of a building and changes a little from picture to picture. Occasionally, it is partly damaged, exposing brick underneath. But it is not more than a synthetic theatrical backdrop, there to set off a face.

Moroni’s neutral backgrounds are subtly different from those in the pictures of other portraitists. The backgrounds in the portraits of Hans Holbein, for example—Moroni’s far-better-known near contemporary and an artist who also specialized in the genre—can be a single uniform color, which suggests a similar emphasis on the face. But Holbein’s colors might be in exquisite shades of blue or green, and they have the same glistening, enamel smoothness as the skin of his people. The effect is that the sitter and the background exist on the same plane, and this makes the face, extraordinarily realistic as it may be, appear to recede a little—to be an image we would find on a page.

Perhaps because of these enameled paint surfaces as well as the reserved expressions of his subjects, Holbein’s images draw us into a kind of late-medieval, fairy-tale-like world. Moroni’s portraits, though, don’t immediately evoke the past, and this is part of their strength. We never get the sense that his individual sitter is part of some metaphorical realm, which can be the case with the portraits of Titian or Lorenzo Lotto, another contemporary of his, or, a half-century later, Rembrandt. Moroni’s subjects make us linger with them because they interest us as people. A strong painting in the exhibition, entitled Gabriel de la Cueva, for instance, presents a formidable character in black and metallic reds—a duke—whose body bespeaks a contained swagger and whose spirit falls somewhere between wary and malign. But might the air of disapproval that he exudes have to do with the way part of his mustache droops over his lip?

Advertisement

What helps make Moroni’s sitters look different from the figures generally seen in old master paintings is a small but telling detail: the haircuts that some of his male subjects have. In pictures here such as The Tailor or Giovanni Gerolamo Grumelli, a view of a cavalier dressed entirely in a coral red—or in the wonderful small-size Portrait of a Twenty-Nine-Year-Old Man, which is not in the show but was seen in 2012 at the Met—we encounter young men whose particular close-cropped heads of hair and closecropped beards make them uncannily like men we see on the street or in the subway today. This is far less the case with figures painted by Holbein, Titian, or any number of later Dutch or French artists. Even Moroni’s middle-aged and older male sitters, some of whom have gone gray or white, can seem to be as much our contemporaries as people of the Renaissance world.

Moroni was a singular painter in sixteenth-century art, Italian or otherwise, and although he was not exactly forgotten thereafter, it was only in the last century that writers began to measure his achievement. For some he seemed significant because his realism could be called a forerunner to the pictures, with their emphasis on the corporeal nature of his models, that Caravaggio would make a few decades later. Other, less persuaded art historians thought Moroni’s work, perhaps because it could appear to be merely a visual record, risked a “shallowness.” But Moroni’s shallowness, which might be called his plainspokenness, has become increasingly alluring.

In 1979 his art in its totality was finally seen in a widely respected oeuvre catalog by the Italian scholar Mina Gregori. Then in 2000 some of his American audience got a chance to see him when the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth put together a small introductory show. It was accompanied by a slim catalog, Giovanni Battista Moroni: Renaissance Portraitist, which includes illuminating articles by a number of writers and remains the most probing study of the artist in English. A more comprehensive look at his art, including aspects of his altarpiece commissions, was provided by “Giovanni Battista Moroni,” an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2014. In its catalog we learn (or are reminded) that the painter was admiringly referred to by George Eliot (in Daniel Deronda) and by Henry James (in The Tragic Muse and “The Liar”).

With its emphasis on the objects in his pictures, the Frick’s exhibition continues this reevaluation of the artist. The show inadvertently makes a point that his admirers may not have thought about. Mostly in his early years, when his patrons tended to be aristocrats in the Bergamo area, Moroni made a number of narrow full-length portraits on canvases that are over six feet high. He eventually created about a dozen, representing about a tenth of his work. Yet of the twenty-three paintings in the show, almost a third are full-lengths, and this turns out to be far too many. They are Moroni at his weakest. In Pace Rivola Spini, for instance, the sitter seems ever so slightly, and beckoningly, impatient. Her face holds us with its psychological veracity. But it is literally stranded at the top of a long canvas that otherwise is uninvolving.

The Tailor, on the other hand, has attracted and somewhat confused viewers for centuries. We see a handsome man of perhaps thirty-five who slightly leans over a table, shears in his hand, about to cut a piece of cloth that has been faintly marked in chalk. He is looking up at us, but his head tilts down, and this sense of a balancing act plays over the picture’s audaciously simplified composition and the larger meaning of the scene.

In a poem from 1660, Marco Boschini put his finger on the work’s two-sided nature when he wrote (in the catalog’s translation) that The Tailor is “so beautiful and well painted that he’s more eloquent than a lawyer.” Many viewers probably agree, feeling that the poised subject, in his elegant white doublet and dusty red trunk hose, with a narrow tan leather belt running along his waist, cannot really be a tailor; and Boschini’s words as phrased also suggest the way that the painting’s beauty and the sitter’s beauty are inseparable.

The picture is the only one in which Moroni shows someone doing something, and it can be thought of as an aberration, or a route he decided not to take. But Arturo Galansino, writing in the London catalog, is also right to say that the painting “embodies the artist’s poetics.” As scholars have noted, making a painting of a tailor, whether as aristocratic a one as we see here or not, is practically unheard of in Italian art of the sixteenth century. That Moroni chose to do it illustrates his openness to the look and spirit of everyday, secular experience, and that openness underlies all his portraiture. It is at the root of his not giving his people airs when they sat for him and his painting a duke no differently than a doctor.

Yet Portrait of a Gentleman and His Two Children, which has been seen before in this country (unlike The Tailor), may be as much of an achievement. It is another rarity for the painter. He did not make group portraits. Yet his composition here, with the brightly colored skirts of the children swaying at the bottom of the scene like tassels stirred by a little wind, is masterful, and Moroni had no problem managing three people at once. With his pointy features and beard, and his right eyebrow at the ready, the red-haired father is all foxy, mentally agile strength. His younger child, who looks out in a not-quite-focused way, provides a kind of pause between him and his older child, whose character is as clear as her father’s.

She turns into his body and touches him even as she turns her head to study us. She looks at us shyly yet with an underlying strength that comes from knowing that she is enveloped by her father. She is an unusual figure for the artist in that she is a kind of actor in a dramatic moment. In this and in the loveliness of her person, she has an unexpectedly and disproportionately large presence in Moroni’s work. It is much like Moroni’s own presence in European painting.