The Literary Club, known simply as “The Club,” was established in early 1764 after the portrait painter Joshua Reynolds became worried about his friend Samuel Johnson, who was sinking into a black depression. An old Oxford friend, William Adams, had visited Johnson the previous autumn and “found him in a deplorable state, sighing, groaning, talking to himself, and restlessly walking from room to room.” Johnson told Adams, “I would consent to have a limb amputated to recover my spirits.” An evening of talk with friends, Reynolds suggested, was a less drastic remedy.

This was an age of clubs, when men met in inns, coffeehouses, and homes, sharing interests ranging from scientific experiments to glee singing—and drink, which played an important part in the Club’s weekly meetings. These took place every Friday in a private room at the Turk’s Head Tavern in Gerrard Street, in Soho. In addition to Johnson and Reynolds, the nine founding members of the new Literary Club included Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, and the magistrate and historian of music Sir John Hawkins (who left after a quarrel with Burke), as well as Burke’s father-in-law, Christopher Nugent, a stockbroker, Anthony Chamier, and two other friends, Topham Beauclerk and Bennet Langton.

The guiding idea, apart from cheering up Johnson, was to have members from leading professions—politicians, lawyers, doctors, and artists—so that they could draw on a wide range of knowledge in their discussions and debates. But the main criterion for members was affability, as Thomas Percy, the first collector of English ballads and a Club member from 1765, later said: “If only two of them chanced to meet, they should be able to entertain each other without wanting the addition of more company to pass the evening agreeably.” The mood of their meetings was loud and convivial. While Johnson hardly drank at all, Reynolds was happy for friends to do so, writing later to James Boswell, “I love the…viva voce over a bottle, with a great deal of noise and a great deal of nonsense.” (That particular evening Reynolds and three others had finished eight bottles of wine, six of claret, and two of port between them.) As for the noise and nonsense, Johnson relished the cut and thrust of argument, or “talking for victory,” as Boswell put it. “There is no arguing with Johnson,” said Goldsmith, “for if his pistol misses fire, he knocks you down with the butt end of it.”

At Club meetings the talk ranged widely. In one session recorded by Boswell in 1778, topics swung from a statue of Alcibiades’ dog to the price of sculpture (and, thereby, the relationship of cost to value), emigration to the colonies, the way travel revealed different sides of human nature, and the degree of guilt one might feel after exposing another to temptation, like laying a purse of guineas before a servant.

By this time, the membership had swelled. New members had to be elected unanimously, and existing members could blackball names they did not like (the musicologist Charles Burney was sore for years after being blackballed by Hawkins, who was writing a rival history of music), but by 1775, a decade after it was founded, there were twenty-three men in the Club. Among recently elected members were David Garrick, Adam Smith, Edward Gibbon, the philologist Sir William Jones, and the politician Charles James Fox.

These powerful individuals could indeed, in their different spheres, be seen as men who shaped their age. But the Club had no shared agenda, and in his engaging and illuminating The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, Leo Damrosch makes no attempt to describe it as a coherent entity, or to follow its development and endow it with a specific part in “shaping an age.” Instead, he uses the Club to give a fresh slant to the more familiar story of the friendship between Johnson and Boswell.

Like mirrors, important members of the Club, described in inset biographical chapters, reflect the milieu and the concerns of the period in different lights. Discussions of Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer and Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals illustrate the complex “spirit of mirth,” while chapters on the work and ideas of Burke, Smith, and Gibbon—unrelated to the Club—raise wider questions of aesthetics and politics, attitudes toward empire and war, social issues and religion. “Lesser lights,” like the aristocratic Beauclerk and the gawky, learned Langton, emphasize particular aspects of Johnson’s character, Beauclerk bringing out an “impulsive playfulness” and Langton his touching humanity.

The differences between members were as crucial as the fellowship. Despite Damrosch’s subtitle, the expanded Club was not always a group of friends: Johnson thought Adam Smith “as dull a dog as he had ever met with,” and both he and Boswell detested Edward Gibbon. Horrified by his religious skepticism, they dubbed him “the Infidel” and “would certainly have blackballed him,” Damrosch writes, when he was put up for membership in 1774 if they had known what he was writing about Christianity in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which would be published two years later.

Advertisement

Damrosch also follows the “shadow club” at Streatham Place, the home of Henry and Hester Thrale, where Johnson lived for long periods, enjoying the Thrales’ company and fine library. It was largely at Streatham that he wrote his final masterpiece, Lives of the English Poets. His “new life at Streatham,” as Damrosch calls it, began in 1765, a year after the Club was formed, and while the Club was a male preserve, the Streatham group, led by the clever, witty Hester Thrale, included a number of remarkable women: Elizabeth Montagu, leader of the bluestockings; the playwright and later moralist Hannah More; and the young Fanny Burney, soon to achieve fame with her novel Evelina, though still firmly under the thumb of her father, Charles. Fanny’s diaries and Hester’s notebooks, which she titled Thraliana, burst with anecdotes and impressions, and the group as a whole opens the way for discussions of the position of women in English society: not only their relationship to men, but the possibility of authorship as a profession for middle-class women, and even the argument for a women’s university. This was put forward by Sheridan, perhaps spurred by the ending of Johnson’s 1759 novella Rasselas, where “the princess thought that of all sublunary things, knowledge was the best; she desired first to learn all sciences, and then purposed to found a college of learned women.”

Around these striking personalities the hectic, noisy life of London itself ebbs and flows and gathers force, like the rapids of the Thames where the tide rolls beneath London Bridge. But if the Club, in Damrosch’s words, is the “virtual” hero of the story, the “real” heroes are Johnson and Boswell. The friendship between the brilliant, lumbering genius and the peacock Boswell, trotting by his side and hanging on every word, forms the overarching narrative. The Club is entirely absent from the early chapters, which are devoted to the lives of this “odd couple” before they met, probing their shared dread of mental illness and suggesting that each may have answered deep, unrecognized needs in the other.

It appears that Johnson, the son of a bookseller from Lichfield, Staffordshire, may have suffered neurological damage at birth, starved of oxygen in a difficult labor. Scrofula, a tubercular illness caught from a wet-nurse that produced hideous swellings and left him nearly blind in his left eye, added to the harm. Despite this, he shone academically, until he was forced to leave Oxford after the death of his father in 1731 left him without funds, and his lack of a degree disqualified him from any profession. Then depression struck, “a morbid disposition” inherited from his father, bringing, he told Boswell, “a dejection, gloom, and despair, which made existence misery.” He felt that this bordered on insanity, and habitual tics, gestures, and odd noises, which he tried vainly to control, strengthened his fear of madness (in Damrosch’s view, Johnson suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder, a syndrome unrecognized in his day, while others have concluded that his disorder resembled Tourette’s).

At the age of twenty-six, Johnson married Elizabeth (Tetty) Porter, twenty years his senior, the widow of a Birmingham cloth merchant. With her inheritance he set up a school, but when it failed in 1737, he headed for London with his former student David Garrick, carrying his blank-verse tragedy Irene in his pocket. In the theater Garrick soon became a star, though Irene found no takers until Garrick himself staged it at Drury Lane in 1749, where its leaden reception cast a shadow over their friendship. Meanwhile Johnson endured long years on Grub Street, working first on The Gentleman’s Magazine, which brought new friendships with brilliant young women such as Elizabeth Carter, translator of Epictetus, and the novelist Charlotte Lennox. While Tetty was intelligent and well read, she was too old and flamboyant to fit into this new milieu—Garrick described her as large-bosomed, with florid red cheeks “produced by thick painting, and…the liberal use of cordials; flaring and fantastic in her dress, and affected both in her speech and her general behaviour.” Soon she retreated to Hampstead, sinking into a lonely haze, “always drunk and reading romances in her bed, where she killed herself by taking opium,” or so Hester Thrale heard.

Tetty’s death in 1752 added to Johnson’s burden of grief and guilt. He was also tormented by the conviction that he was hopelessly lazy, chastising himself for endlessly breaking resolutions by “negligence, forgetfulness, vicious idleness, casual interruption, or morbid infirmity.” In fact he worked tirelessly. He drew attention with the poems “London” and “The Vanity of Human Wishes,” as well as his magazine The Rambler, and after a decade of labor he completed his magnificent Dictionary in 1755, its myriad quotations charting “the boundless chaos of a living speech.” Now famous, he was, however, still broke, until his near destitution was relieved by a pension from the Crown in 1762.

Advertisement

Johnson was fifty-four when he met the twenty-two-year-old James Boswell in Thomas Davies’s Russell Street bookshop on May 16, 1763. Boswell had read The Rambler and Rasselas, and considered Johnson the fount of all wisdom. Soon, amused by Boswell’s easy chatter and evident devotion, Johnson accepted him as a friend: “Boswell, I think I am easier with you than with almost anybody,” he told him later. Their friendship would last until Johnson’s death in 1784. In his Life of Samuel Johnson, though not in his journal, Boswell presented their first meeting in dramatic style, with Davies announcing Johnson’s arrival in the words of Horatio alerting Hamlet to his father’s ghost: “Look, my Lord, it comes.”

In Johnson, Boswell found a father-figure very different from his own father, the stern Lord Auchinleck, a high-ranking Scottish judge and strict Calvinist. Boswell said that the only thing his father taught him, hammered in with a beating, was the habit of telling the truth, which, as Damrosch notes dryly, was at least “a great asset in recording the conversations of Johnson and other friends.” Even as a teenager Boswell kept a journal. He was a clever mimic, good singer, and terrible poet (though not in his own estimation). After university in Edinburgh, and then in Glasgow, where he was a student of Adam Smith, he escaped to London, only to be hauled north again by his father. Finally, in November 1762, having passed his examination in civil law, he returned to the capital, harboring dreams of a glamorous life in the Foot Guards.

Boswell’s bounce was countered by frightening depressions, a curse suffered by his grandfather and his uncle John. His mood swings support the modern diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and Boswell himself vividly describes the void when depression struck for no apparent reason. One day, he wrote, he might be “very high-spirited and full of ambition.” On another, “Melancholy clouds my mind, I know not for what. But I resemble a room where somebody has by accident snuffed out the candles.” But if Johnson and Boswell shared a terror of madness and despair, “their personal styles were so different,” Damrosch writes, that “they represent a double helix of possibilities”:

Boswell was a romantic who fantasized about feudal affection between lords and their dependents, Johnson was a hardheaded pragmatist. Johnson insisted on reason and self-control, Boswell reveled in emotional “sensibility” and seized gratifications whenever he could. Johnson aspired to what he called “the grandeur of generality” and Boswell to specificity and piquant details. Johnson crafted language in the carefully assembled building blocks of the periodic style, Boswell’s style was conversational and free.

For Johnson, Boswell provided a bulwark against creeping old age. But the younger man was, as Damrosch notes, far more than a disciple.

Soon after their first meeting Boswell set off on his Grand Tour, making a stop in Corsica where he met the rebel leader Pasquale Paoli (who later, in exile, became a friend of several members of the Club), and in Switzerland meeting with a cool Voltaire and a slyly amused Rousseau. (The amusement faded fast when news spread that Boswell had managed to sleep with Rousseau’s mistress, Thérèse Levasseur, on his way home.)

In the winter after Boswell left, Reynolds dreamed up the Club, and at almost the same time the Thrales invited Johnson to Streatham. Neither group would affect Boswell’s closeness to Johnson, although in both Boswell was made to feel an outsider. When he returned from the Continent in 1766 he was madly keen to join the Club, but the core members considered him merely “an agreeable lightweight” and he was not admitted until 1773, after Johnson insisted. (Five years later, Johnson himself dropped out, dismayed by the growing number of members.) At Streatham, where Hester was the star, Boswell felt uncomfortable, drank and talked too much, and was mocked for his spaniel-like devotion to Johnson.

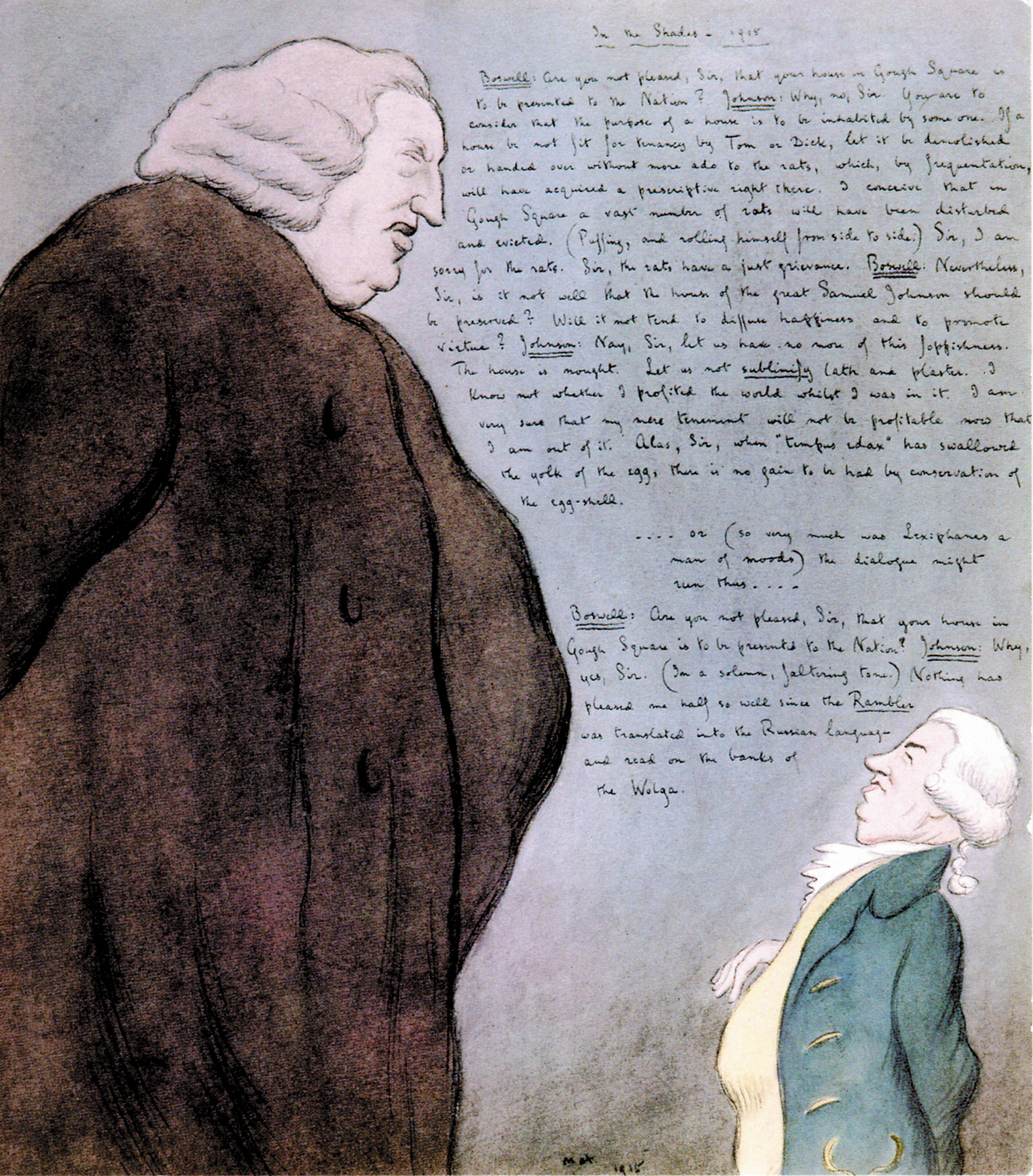

Concerned that we should see, as well as hear, these groups, Damrosch includes a superb array of color plates and black-and-white illustrations, ranging from Rowlandson’s tumultuous crowds to a portrait of Fanny Burney in a piled-up hat, adding height to her diminutive stature. In the Club and the Streatham group, it always mattered what people were wearing, and they appear before us here in distinctive style: Johnson in his rusty brown suit and crumpled worsted stockings, with his “shriveled wig” too small for his head; Boswell calling on Lady Northumberland in a “genteel violet coloured frock suit”; Goldsmith compensating for his squat form with flashy clothes, walking out in a “bloom-coloured coat,” a light pink that Johnson found “absurd.”

For Reynolds, the first president of the newly formed Royal Academy of Arts, clothes were mere drapery, left to his many assistants while he concentrated on his sitters’ faces. “Even in portraits,” he wrote, “the grace, and we may add, the likeness, consists more in taking the general air than in observing the exact similitude of every feature.” He imparted dignity even to the pudgy profile of Goldsmith, one of his dearest friends.

While Reynolds fitted his practice with his theory, celebrating great masters for representing ideal types rather than individual quirks, and relying heavily on Johnson’s dictates about the value of “general truths,” this approach irritated some of his friends, as well as critics like William Blake. Was this idealization simply flattery of rich patrons? Was he driven less by deep-held theories than by a desire for success and money? Reynolds’s selfishness is implied by his suppression of the talent of his sister Frances, known to friends as “Renny.” But this was equally a mark of the age: Johnson, too, approved of her decision not to paint professionally (in his view, gazing into faces while painting portraits might inflame desire), just as he praised the brilliant singer Elizabeth Linley for retiring after she married Sheridan. But he did let Renny paint him. Her portrait, revealing his stooped, massive form and steady gaze, is, as Damrosch says, “tender yet unsparingly honest…a portrait that Sir Joshua would never—indeed could never—have painted of their friend.”

The theater also saw a tension between idealization and “realistic” character. Playing Richard III in 1741, a role that made him a star overnight, Garrick stunned audiences with his apparent naturalism. “Good heaven—how he made me shudder whenever he appeared!” wrote Fanny Burney. Today, his famous “start” as he wakes from ghost-filled dreams on the night before his death at Bosworth Field, immortalized in William Hogarth’s painting of 1745, looks unredeemably stagey, yet to his audiences he seemed to be the characters he played, from Hamlet to the comedic Abel Drugger in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist.

Boswell’s love of role-playing echoed Garrick’s acting in a comic mode, nicely illustrated at Garrick’s Great Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford in 1769, a famous fiasco, wiped out by torrential rain. Most of the Club stayed away, sneering at the commercialism of the event, but Boswell swiftly ordered from a London tailor a copy of a costume brought back from Corsica (he had left the original in Edinburgh), strutted happily through the downpour, and had his portrait as a Corsican chief engraved for the London Magazine. In a restaging at Drury Lane, where Garrick recouped all his costs and then some, one of the actors, borrowing the costume, appeared as James Boswell.

A different kind of acting marks the career of Edmund Burke. Like Johnson and Goldsmith, the Dublin-born Burke was working as a hack writer when he published his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful in 1757—all three may have met in their Grub Street years. As with Garrick’s performances, Burke’s psychological approach to aesthetics was excitingly new: the “beautiful,” associated with smoothness and delicacy, gave rise to calm, detached pleasure, while the “sublime,” prompted by the roughness of frightening landscapes or unsettling works of art, raised feelings of terror and awe. (Johnson found little sublime on his tour of the Scottish Highlands with Boswell in 1773, writing off the mountains as “matter incapable of form or usefulness, dismissed by nature from her care.”)

From the mid-1760s, Burke won fame as a thrilling political orator in Parliament. Some critics were suspicious of him, an Irishman of Roman-Catholic parentage. Others deemed him too fond of his own voice. As Boswell wrote cannily:

It was astonishing how all kinds of figures of speech crowded upon him…. It seemed to be, however, that his oratory rather tended to distinguish himself than to assist his cause. There was amusement instead of persuasion. It was like the exhibition of a favourite actor. But I would have been exceedingly happy to be him.

Johnson enjoyed sparring with Burke. But on a deeper level, both men shared a profound belief in the value of “subordination,” the importance of preserving traditional, hierarchical structures, and the benefit of slow, rather than sudden, change. “The progress of reformation,” Johnson wrote, “is gradual and silent, as the extension of evening shadows.” When Boswell remarked that Johnson must then laugh at schemes of political improvement, he replied, “Why, Sir, most schemes of political improvement are very laughable things.”

Laughter does not always imply mockery. Johnson loved to laugh—Davies said he laughed “like a rhinoceros”—and one can almost hear his great, rumbling guffaw. This was loudest among the relaxed company at Streatham. There the women joined in freely, and Johnson egged them on, as in a dispute one evening between the celebrated Elizabeth Montagu and the young Fanny Burney, “little Burney,” to whom he was always kind. Fanny recalled his “countenance strongly expressive of inward fun” and his sudden admonition to attack Montagu relentlessly: “When I was new, to vanquish the great ones was all the delight of my poor little dear soul! So at her, Burney!—At her, and down with her!”

There was, maybe, more to life at Streatham than laughter, and Damrosch also considers Hester in the role of therapist. Listed in her effects at her death was “Johnson’s padlock committed to my care in the year 1768.” Although Johnson may have bought a padlock and fetters in genuine fear that he might have to be restrained if he went mad, Damrosch suggests there was a psycho-sexual element in his dependence on Hester: that this tiny, forceful woman may have fulfilled a longing for restraint or physical correction. While Boswell took women as often as he could, in alleys and dark corners, even after his marriage in 1769 to his cousin Peggie Montgomerie, Johnson’s strong sensual urges, another spur to guilt, were ferociously suppressed. Where Boswell looked on prostitutes as prey or dangerous carriers of the clap, Johnson saw them as individual women, victims of fate, miserably trying to make a living by “the drudge of extortion and the sport of drunkenness.”

One former prostitute, Poll Carmichael, was among the dependents who clustered around his rooms in Bolt Court off Fleet Street, his London base after 1776. This domestic coterie, roundly sneered at by Hester Thrale, included the learned Anna Williams, blind and irritable, with whom visitors were expected to have tea; Tetty’s former companion Elizabeth Desmoulins; Francis Barber, Johnson’s servant; and the unlicensed Dr. Levet, who treated the poor for free. Johnson was far from sentimental about this odd, often squabbling group, a very different kind of club.

Damrosch is a crisp guide to everything from rhetorical styles to the gallows at Tyburn, where prisoners from Newgate were executed. Like a benign lecturer fixing his audience with a stare over his glasses, he alerts us to crucial points with a nod: “It’s important to understand…” or “It needs to be stressed…” He wears his learning lightly, and his sympathetic enjoyment is infectious. When Boswell arrives in London, declaring that he feels his mind “regain its native dignity” and deciding to aim at an ideal character, mixing Addison’s “propriety” with “a little of the gaiety” of Steele or the dashing actor West Digges, Damrosch writes, “This is touchingly earnest, and touchingly confused. ‘Native dignity’ was just what Boswell never had…. And what a curious set of role models!”

While Damrosch’s insights into the characters and achievements of Johnson, Boswell, and the leading Club members are astute, he is also generous in his acknowledgment of other commentators. These evoke a body of readers over time that includes some unexpected voices: Max Beerbohm scribbled an inspired parodic exchange between Boswell and Johnson, complete with a sketch of the two men, and Samuel Beckett drafted a play about Johnson’s dependents, Human Wishes. In one scene, where the women sit, knit, and read, Dr. Levet enters “slightly, respectably, even reluctantly drunk,” hiccups, does nothing at all, and exits:

MRS. WILLIAMS: Words fail us.

MRS. DESMOULINS: Now this is where a writer for the stage would have us speak, no doubt.

In The Club, as the actors appear one by one, surrounding Johnson and Boswell on Damrosch’s stage, we are transported back to a world of conversations, arguments, ideas, and writings. And in this vibrantly realized milieu, words rarely fail.

This Issue

May 23, 2019

An Indictment in All But Name

A Different Kind of Emergency