Every year, on December 17, sex workers from Bombay to Zagreb gather to demand that the world stop killing their colleagues. The International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers started in 2003, to commemorate the dozens of women murdered by the Green River Killer in Washington State in the 1980s and 1990s, and has since grown into a collective cry of mourning, solidarity, and sex workers’ refusal to be ashamed.

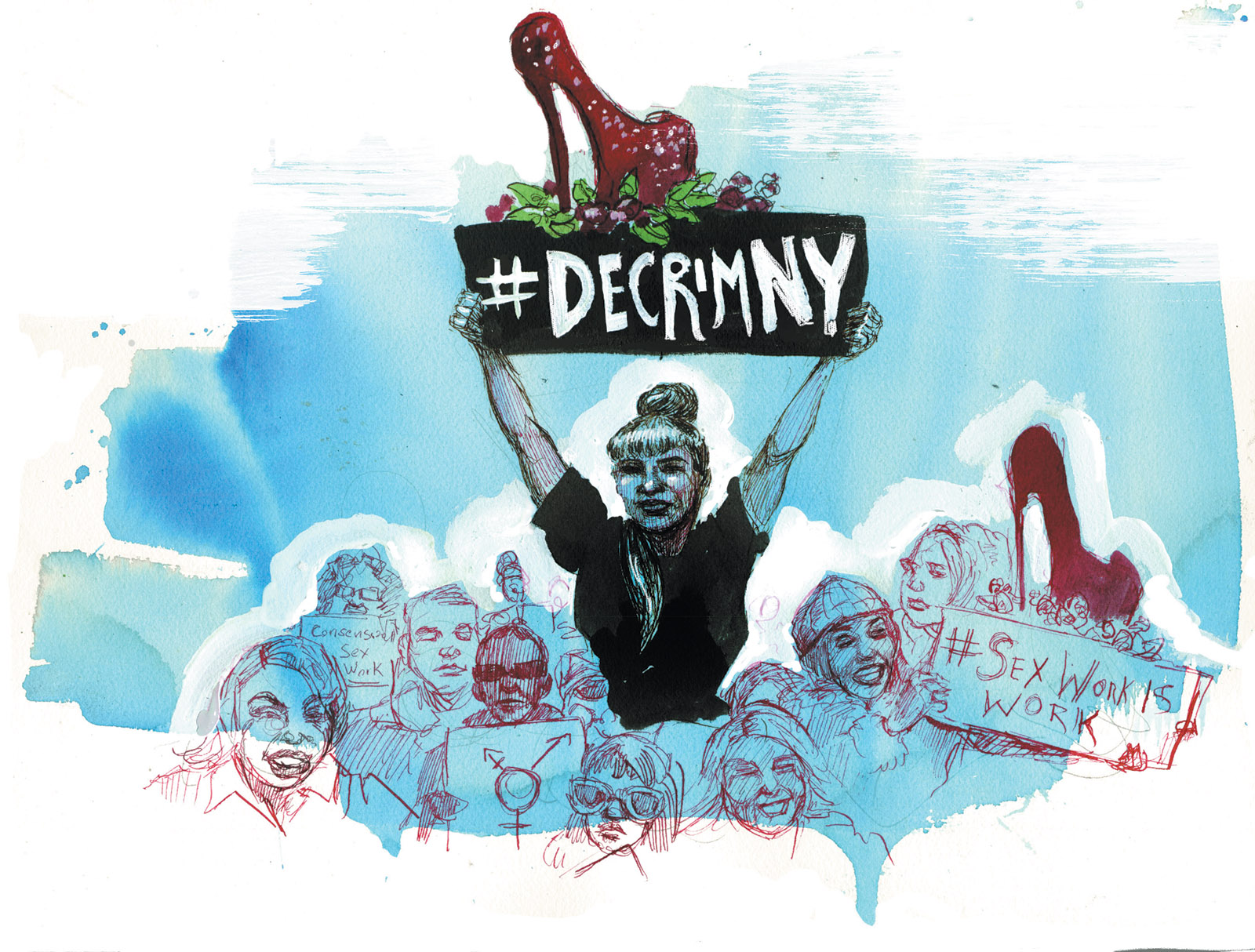

American sex workers are today more organized, and more oppressed, than they have been in years. Last year the US government passed the twin laws of SESTA and FOSTA—the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, respectively, which have closed online spaces where sex workers found clients and shared information—forcing them to work with pimps or to work on the streets where they may be beaten and murdered. Sex workers have responded with ferocious activism. Collectives like Survivors Against SESTA and the Sex Workers Project are lobbying, marching, and canvassing to overturn these laws. More surprisingly, Democratic politicians like New York state senators Jessica Ramos and Julia Salazar have listened to them, canvassed with them, and even promised to introduce laws to decriminalize prostitution.

On February 22 sex trafficking made its way into the headlines when New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft, a billionaire septuagenarian and Trump crony, was arrested during a series of prostitution stings on massage parlors in three Florida counties and charged with two misdemeanor counts of soliciting prostitution. During the seven months police spent investigating the parlors, they secretly installed cameras in massage rooms and made videos of the women as they gave handjobs to their customers. The Vero County police department refused to answer questions from sex workers’ rights advocate Kate D’Adamo as to whether their officers had had sexual contact with any of these women in the course of their investigation, but one detective confirmed to the sports website Deadspin that he had.

Police described the investigation as an anti-trafficking operation, but no trafficking charges have been made. Four women who ran the massage parlors were arrested. Among other crimes, they were all charged with prostitution. All of them have spent more time in jail than any of the men they allegedly serviced.

While the media lingers on the spectacle of Kraft’s disgrace, sex workers and trafficking survivors are advancing in their battle to be heard. In February, I stood in the freezing cold of New York’s Foley Square at a rally called by sex workers’ groups to demand decriminalization and listened to Julie Xu, an organizer at Red Canary Song, a collective of Asian massage parlor workers.* A slight woman with a short pixie haircut, Xu spoke with eloquent fire: “The raids must stop, and the police violence in the name of raids. Police, ICE, rescue industry lackeys, out of the parlors.”

At the rally, Xu was preceded by local politicians who promised to decriminalize sex work—something unthinkable even two years earlier. But a month later, I saw a breakthrough just as great. When two New York City Council members announced a new crackdown on massage parlors, local reporters did not just reprint their press release or blithely praise them. They asked Red Canary Song for comment. The women’s demands were clear:

We want [the council members] to recognize the humanity of these workers and protect them, rather than do violence to them through sweeps, evictions and surveillance. We want the people of Queens to stop looking away in shame, and recognize that these people are part of our communities and they deserve to be treated with compassion and respect.

Though international in scope, Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights by the UK-based Juno Mac and Molly Smith is an essential guidebook for this American moment. Mac and Smith are both sex workers themselves, and they write with the swagger of new arrivals at a party where, until recently, the bouncer had been warned not to let their kind past the door. Revolting Prostitutes begins with a refusal: “This is not a memoir.” They will not offer up titillating autobiographies for the reader’s satisfaction. Instead, they will write about sex work as a job that, while not exactly like any other, still contains the sorts of tensions, vexations, financial pressures, and freedoms that define the lives of other precarious workers under capitalism.

Like so many issues involving women, debates about sex work are often bogged down in the question of whether sex work itself is “degrading” or “empowering.” Mac and Smith reject this dichotomy from the start. “This book—and the perspective of the contemporary left sex worker movement—is not about enjoying sex work,” they write. Work need not be a good time for workers to deserve autonomy, respect, safety, and better pay. The British coal miners who battled Margaret Thatcher hardly claimed that their coal pits were fun. The question “Is sex work good?” has little to do with “Should sex workers have rights?” But this obvious truth is often ignored by writers who get hung up on the “sex” part, painting sex workers as brainless bimbos or voiceless victims. “Sex workers are associated with sex, and to be associated with sex is to be dismissible,” Mac and Smith write.

Advertisement

This approach feels revolutionary because conversations that people not engaged in sex work have about it tend to involve a stew of unspoken anxieties about not just sex but migration, disease, race, class, and the roles of women. The living, human sex worker gets blotted out by the cultural figure that journalist Melissa Gira Grant has dubbed the “prostitute imaginary.” This mythological creature is both corruptrix and release valve for male corruption. She is the temptress locked away to toil in the Magdalene Laundries, the disease spreader, the frivolous blonde with her Louboutin shoe collection, the soul broken by too much sex. And for many feminists, she is the ultimate example of female victimhood—in activist Dorchen Leidholdt’s words, a “de-individualized, de-humanized” proxy for “generic woman…. She stands in for all of us, and she takes the abuse that we are beginning to resist.” Once a sex worker becomes a metaphor, her material conditions cease to matter. She is an object for study, ministration, and control.

Real sex workers are as various as humans in general, united only in the fact that they do this particular job. Most “work is often pretty awful, especially when it’s low-paid and unprestigious,” Mac and Smith write. This includes sex work. All the more reason to prioritize the well-being of the workers, poor or rich, miserable or happy, men and especially women. The authors’ focus on the worker lets them say things that even fellow activists seldom mention in public, for fear their words will be used against them. Some sex workers are raped. Some are coerced. Some clients are abusive. Some sex workers loathe their jobs. Some want desperately to leave, and would, if society made any better options available.

But better options are hard to come by, especially for those on the margins. People sell sex in order to make money, and “prostitution is an abiding strategy for survival for those who have nothing.” The authors quote many women like Dudu Dlamini, of South Africa, who turned to sex work as an escape from the drudgery of subsistence domestic labor. The more easily workers can make money, the more able they are to be picky about clients or fight for better conditions. Yet money hardly figures at all in discussions by anti-prostitution campaigners. In one meeting held at the Scottish Parliament between sex workers and a government minister, the workers spoke briefly about the immigration problems, single motherhood, or homophobia that had led each of them to become prostitutes. The minister “observed that we all seemed to have started selling sex in order to get money, in a tone suggesting…that she was slightly incredulous,” Smith reported. Policy reflects this disconnect; states like Texas combine punitive laws against pimps and traffickers with a complete lack of funds for trafficking victims, let alone for programs to fight the poverty that so many people turn to prostitution to escape. Cash, not sex, is the desire we dare not name.

Perhaps no prostitute archetype raises so much lucrative concern as the trafficked girl. This figure of feminine vulnerability was born during the white slavery panic of the nineteenth century, such as when a missionary from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union claimed that “white girls—thirteen, fourteen, sixteen, and seventeen years of age…are snatched out of our arms, and from our Sabbath schools and from our Communion tables,” presumably to sexually service foreign men. Similar fears were the justification for the Mann Act, which forbade the transportation of women across state lines for “immoral purpose”; it was often used to prosecute interracial couples. The trope of the stolen innocent has lasted into the twenty-first century. In 2008 it reached its apogee in the schlocky Liam Neeson vehicle Taken, where the innocent is the daughter of a former CIA agent. Dad must rescue her from the clutches of swarthy Albanian sex slavers after she disobeyed him by vacationing in Paris. When a girl crosses a border, who knows what trouble it will bring?

In popular discourse, the trafficked girl is never a woman who crossed borders willingly, to do sex work of her own volition, but who was lied to, threatened, or beaten once she landed. Nor is she an undocumented migrant pushed into sex work because her only other options involved back-breaking, sub-subsistence toil. She is passive, preferably white, a child or at least childlike victim, who has been kidnapped and raped by pimps. She is often portrayed in anti-trafficking ads as a white girl with a dark hand clapped over her mouth, or loomed over by a dark shadow. Even the names of anti-trafficking NGOs highlight her nubility: Lost Innocence, Saving Innocence, Freedom4Innocence, the Protected Innocence Challenge. She provokes no messy debates about borders, imperialism, or labor. Her existence is apolitical. She can be saved.

Advertisement

By championing this figure, governments, corporations, and NGOs can demonstrate their virtue without inviting any challenges to their own power. Mac and Smith note:

In the United States alone, the collective budget of thirty-six large anti-prostitution anti-trafficking organizations…totalled 1.2 billion dollars, while the US federal government budgets a further $1.2 to $1.5 billion annually for anti-trafficking efforts. The vast majority of this money is spent on campaigning, as opposed to supporting survivors.

Crusaders against trafficking can blur easily into persecutors of immigrants. When Trump e-mailed supporters in March to drum up support for his wall, he cited stopping sex trafficking as one justification. In an exhibition in Houston, an anti-trafficking organization set up a museum of “modern-day slavery,” displaying a prostitute’s high-heel shoe next to an enslaved African’s shackle. They did not mention that the woman to whom the shoe belonged had kicked if off in order to run from the police.

As for actual immigrant women who are trafficked, they may be in bondage in a brothel, but they are far more likely to end up as maids, on shrimping boats, picking cabbage in Lincolnshire, or in any of the other countless positions in which undocumented migrants from poor countries toil. Mac and Smith write that trafficked, exploited migrant workers are “victims of problems that are systemic and largely originate from the state, rather than from individuals”—vulnerable because immigration to wealthy countries is so difficult that they have had to rack up debts to criminals. Border controls distort a person’s options, pushing them toward work they never before would have considered.

Mac and Smith delineate the problems of sex workers in all their prosaic complexity. “A sex worker may describe a bad experience as a labour-rights violation, sexual abuse, or simply a shitty day at work,” they write. Against the stereotypical Happy Hooker, they talk about the “unhappy hooker,” forced, like so many other workers, to do work she loathes in order to earn enough money to survive, and “who reminds us that capitalism cannot be magicked away” by a jail cell or a self-help book for aspiring Girlbosses—and that capitalism reigns most brutally in criminalized markets. Precisely because the safety net is weakest for marginalized people, they are more likely to become sex workers. Clients, like bosses, are seldom allies, precisely because they have more power than the workers they hire. Mac and Smith describe a boycott that clients organized on Internet forums against escorts in their area to force them to drop their rates. Like other workers, sex workers are happier with their situation when they make more money, have more control over their working conditions, and can more easily afford to say no.

So what is to be done? “We want readers to think empathetically about how changes in criminal law change the incentives and behaviours of people who sell sex, along with clients, police, managers, and landlords,” Mac and Smith write. In four exhaustive chapters, they examine different legal regimes that govern sex work around the world—from prosecutions of clients, managers, and workers in the US to near-complete decriminalization in New Zealand. They are careful to not just explain what the laws mean in theory but to show the consequences for sex workers in practice.

Prostitution laws primarily target women of color. Between 2012 and 2015, 85 percent of those booked in New York City under the dubious “loitering for the purpose of prostitution” charge—which encompasses such innocuous behaviors as wearing tight jeans and carrying condoms—were black and Latina women. And while prosecution of sex workers is sometimes justified as a way of saving them from exploitation, police too are sometimes rapists. The authors quote a young Chicago sex worker caught by an undercover cop posing as a client: “He got violent with me, handcuffed me and then raped me. He cleaned me up for the police station and I got sentenced to four months in jail for prostitution.”

The criminalization of sex work also comes with a body count. In 2009 Marcia Powell died of heatstroke in an outdoor cage in an Arizona prison while serving a twenty-seven-month sentence for prostitution. In 2018 a sex worker, Donna Dalton, was shot to death by undercover police officer Andrew Mitchell in Columbus, Ohio; he alleged she had stabbed his hand while he had her trapped inside his car, the passenger-side door flush against a wall. Six months later, Mitchell was indicted for kidnapping and raping sex workers, and he was indicted for Dalton’s murder in April. By moving sex workers out of specific areas, criminalization forces women to work on unsafe streets where they can be attacked by clients or criminals. After police banished Paula Clennell, a poor, addicted sex worker in Ipswich, England, from working on busy streets, she saw her clients in isolated places where she felt safer from arrest. There she, along with four other women, was murdered by a client.

Many anti-prostitution feminists are uncomfortable with the prosecution of sex workers. Why should prostitutes—the sex industry’s ostensible victims—be handcuffed, thrown in the back of police cruisers, and locked in cells? But to these feminists, decriminalization would be a capitulation not just to traffickers, but to female objectification more broadly. To cut this Gordian knot, they advocate what’s often called the Nordic model, which criminalizes clients and managers but not sex workers. First passed in Sweden in 1999, the sexköpslagen—or sex purchase ban—was meant to end demand for prostitution and diminish the often violent power of the patron and the pimp. A sex worker might find herself poorer, yes, but it was for her own good—as well as the good of women in general.

Unfortunately, it didn’t work out this way. Though they no longer charged sex workers as criminals, Swedish courts still viewed them as psychologically unfit. In 2013 Swedish activist Petite Jasmine lost custody of her children because she did sex work. Courts placed the kids with her abusive ex-partner, who stabbed Jasmine to death when she came to pick them up for a visit. “The bloody state gave him power,” a fellow activist later said. On the streets, fewer and more skittish clients meant sex workers couldn’t be choosy. They had to accept worse clients, with fewer safety checks, for lower fees.

For indoor sex workers, the Nordic model is equally dangerous. Police evict women from their homes and charge women with pimping if they work together in one apartment. In Ireland, where the Nordic model is also in effect, police confiscate prostitutes’ money as the “proceeds of crime.” In 2017 seventy-three-year-old Terezinha sold sex to one client in Ireland in order to pay for her son’s medical bills but made the mistake of sharing her room with another sex worker; her eighty euros were taken by the court to help “women involved in the sex trade.” For migrants, the consequences are even more dire: a single arrest may lead to their imprisonment or deportation. “When you are Black, [police] take the Black women and leave the white man,” says Tina, a Nigerian sex worker in Norway.

Feminists can only continue to support the Nordic model if they ignore the people it’s supposed to be helping. Revolting Prostitutes documents this disdain. Anti-prostitution feminists call sex workers “flesh holes” and “blow-up dolls,” whose jobs are as harmful to society as those of oil executives. Anti-prostitution academics Cecilie Hoigard and Liv Finstad referred to a sex worker’s vagina as “a garbage can for hordes of anonymous men’s ejaculations.”

As a solution, some American libertarians trot out the motto “Legalize, tax and regulate.” Legalization is in practice all over the world, from Turkey and Germany to Amsterdam’s famous red light district and the brothels of Nevada. While the precise definition of legalization varies from place to place, it generally means that sex workers can only work in specific establishments and must be licensed and subject to regular medical checks. This is supposed to allow for prostitution while preventing disease and crime. But “contrary to its false reputation as a benign sex fun-fair, a regulationist legalisation approach to prostitution is not friendly for sex workers,” Mac and Smith write. It creates a rigid hierarchy of tightly controlled prostitutes and powerful, potentially exploitative bosses. Like the women who lived in the maisons de tolérance of nineteenth-century Paris, legal prostitutes are monitored, tested, confined to brothels, and registered. Prostitutes who are undocumented immigrants, or who are unable or unwilling to obtain permits or licenses, form a “vulnerable, criminalised ‘underclass.’”

Instead, the authors suggest decriminalization, which is practiced in New Zealand and New South Wales, Australia. Complete decriminalization—or the removal of criminal penalties for both buying and selling sex—is the unanimous preference of the global sex workers’ rights movement, as well as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the World Health Organization. Unlike legalization, it doesn’t impose a regime of permits and laws that need to be enforced; instead, it takes police out of prostitutes’ lives and workplaces. By removing the fear of surveillance, raids, and arrest, decriminalization lets prostitutes work in the conditions that best suit them, and allows them to collectively organize for their rights. In a study commissioned by the New Zealand Ministry of Justice, 96 percent of street-based sex workers said they felt they had legal rights. New Zealand is no utopia—migrant sex workers are still criminalized, social welfare programs are still underfunded. But, says one sex worker there, decriminalization “changed the whole street, it’s changed everything. So it was worth it.”

Blowin’ Up, Stephanie Wang-Breal’s documentary about the Queens Human Trafficking Intervention Court (HTIC), showcases some of the very approaches to sex work that Revolting Prostitutes spends so much time critiquing. In this exquisitely filmed love letter to carceral feminism (the notion that gendered violence can be redressed through policing and prosecution), judges, prosecutors, and NGOs team up to help young women who have been arrested for prostitution, even if they have to threaten them with jail to do it.

Judge Toko Serita founded the court in September 2013, and its model was soon replicated across the country. In an HTIC, women—for it is almost entirely women—arrested for prostitution have the option of avoiding a criminal charge by signing up for a series of counseling sessions provided by a court-affiliated nonprofit. The woman does not have to plead guilty, but she cannot fight the charges either. By giving alleged prostitutes the option to receive their sentences in counseling rather than jail time, HTICs aim to provide a redemptive, therapeutic justification for their often violent arrests. Police may be grabbing women off the streets, but they bring them to a courtroom run by a woman, who sentences them to talk with (mostly) other women, thus, it is thought, helping them leave prostitution for a productive, middle-class life.

In 2015 I spent months reporting on New York’s Human Trafficking Intervention Courts in the Bronx and Brooklyn. Each day of court is the same as the last, and Blowin’ Up presents this as a ritualistic repetition. Judge Serita enters. The women’s names are read. A woman walks up to the docket, flanked by a public defender. She is probably a woman of color. (In Brooklyn, black women make up nearly 70 percent of prostitution defendants, 94 percent in cases of loitering with intent. In Queens, 58 percent of defendants are Asian.) She is exhausted, frightened, or fed up. The prosecutor, Kim Affronti, offers her a certain number of counseling sessions. The defense attorney agrees. Judge Serita tells the woman to complete the program and not to get arrested, then wishes her luck. It all takes a few minutes. Gavel down. On to the next.

Though Blowin’ Up does not mention it, services are scant for both sex workers and trafficking victims. The court connects defendants with classes and counseling, but does not offer money or a place to live—the very things most crucial for anyone trying to escape a trafficker or just a job they loathe. As Revolting Prostitutes notes, “In 2014, the United States had only about one thousand beds available for victims of trafficking.” “Classes do nothing for you,” a Bronx sex worker named Love told me in 2016. “After that class ends, where do I sleep, how do I eat, do I still have to hide from the pimp?”

Unsurprisingly, women often end up right back in the HTIC. “Did I arraign you? Yes I did!” Judge Serita chirps, upon seeing one young defendant again. But she’s pleased the woman will be going for court-mandated counseling. “Are you happy too?” The defendant bashfully demurs, but admits she’s happy to see her social worker, standing next to her. “I’m just upset I’m here.”

During recess, counselors rush to help defendants with their sessions. There’s charismatic, fast-talking Eliza Hook, a social worker for Girls Educational & Mentoring Services (GEMS). She plainly adores the young women she works with, getting them new IDs, boxing lessons, and MetroCards, and giving them hugs. Like her fellow counselor Susan Liu, the associate director of women’s services at Garden of Hope (a nonprofit dealing with social problems in the Asian community, including sex trafficking), Hook sees young women who have experienced the whole range of trauma. “We don’t think you’re a criminal, and we don’t think that this should be happening to you,” Hook says. “Our main concern and our loyalty lies with you.” Later in the film, she clinks glasses with Judge Serita and Kim Affronti during her going-away party at a swish cocktail bar. Judge, prosecutor, counselor—all are on the same team.

Blowin’ Up does not document the cocktail bars where sex workers party, or give them family portraits like those of Judge Serita and her wry, charming mom (these are among the film’s most tender moments). When these women speak at all, it tends to be in court, or during a court-mandated appointment with Hook or Liu. Their experiences follow no single script. “I don’t think I was human trafficked,” says one sex worker who once traveled across the country with a pimp who stole her money. “I made that choice to do that. I ended up putting myself into those situations and I can’t help that, but that’s life. Life is hard.” Another defendant shocks Judge Serita by proclaiming her innocence. “I must speak out what happened…because it’s the right choice,” she says through a translator. Judge Serita warns her that, should she be found guilty at trial, she would be deported.

Judge Serita’s HTIC has done some good for some women, but the question remains why such a notoriously violent police force has to bring them there. In 2017 two NYPD officers allegedly handcuffed and raped a teenager, Anna Chambers, in the back of a police van, and sex workers have told me that officers held addicted women in their cars until they went into withdrawal, then extorted sex. To its credit, Blowin’ Up does allude, once, to the brutality of these arrests. In a scene shot in a restaurant on a smeary, exoticized Chinatown night, a young Chinese sex worker speaks with Liu. “Of course I didn’t want to get arrested…they were too rough, and they hurt me,” the young woman says. “And nothing was clear.” “Do you feel like they violated your human rights?” Liu asks, seemingly unaware of her own, or the court’s, complicity. The young woman nods.

This is as far as it goes. Blowin’ Up avoids mentioning Yang Song, a Chinese sex worker who had once passed through Judge Serita’s courtroom. Song had nearly completed her five mandatory counseling sessions when, on November 25, 2017, she fell to her death from a window during a vice sting on the Queens massage parlor where she worked. Whether she fell or jumped, no one knows. Reporting by Melissa Gira Grant and Emma Whitford, journalists who have tirelessly followed Song’s case, offers some insights into why she might have fled. In October 2016 Song filed a police report alleging she had been sexually assaulted at gunpoint by a man posing as an undercover officer. Her family told Grant and Whitford that the police had tried to make her an informant. (Red Canary Song was formed following her death.)

Only one news item leaks into the film’s storyline—the election of Donald Trump. Goaded on by Trump’s zero-tolerance policy, ICE began arresting immigrants at courthouses in 2017—and found an easy hunting ground in the HTIC in Queens. Blowin’ Up captures the panic after three women are snatched and two likely deported back to China. At the denouement of Blowin’ Up, Judge Serita stands before a roomful of her colleagues and admits that her much celebrated model is not “a safe space” for the women it claimed to champion. The court she built has become a trap. As is the case with so many Trump-induced realizations, Serita’s epiphany came far too late. Sex workers like Juno Mac and Molly Smith could have warned her.

-

*

See my “‘Whores But Organized’: Sex Workers Rally for Reform,” NYR Daily, March 11, 2019. ↩