1.

Late-nineteenth-century Chicago is widely deemed to have been the crucible of modern architecture in this country—the birthplace of the skyscraper, the city that nurtured Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and a host of other innovators dubbed the Chicago School. After World War II, Los Angeles—enlivened by an influx of émigré architects from Europe and young American coprofessionals attracted by a booming, prosperous population amenable to new ways of living—became the country’s foremost center for experimental design, culminating in the late-twentieth-century phenomenon of Frank Gehry. Yet every so often, towering if idiosyncratic master builders have emerged from the supposedly conservative milieu of Philadelphia, which has always been overshadowed by New York City, the financial and cultural powerhouse eighty miles to the northeast.

From the 1950s onward, the more searching eyes of the architectural world were focused on Philadelphia’s Louis Kahn, who by the time of his death in 1974 was considered the world’s preeminent architect, largely because he abjured commercial compromises that had diminished the profession’s artistic authority.1 During the 1960s Philadelphia became even more of an architectural cynosure with the influential husband-and-wife team of Robert Venturi (who’d worked for Kahn) and Denise Scott Brown (who’d studied with him at the University of Pennsylvania), controversial for their irreverent Pop references.2

But a century before them all, the exemplar of the rogue Philadelphia architect, full of boundlessly stimulating invention and unconcerned about fashionable developments elsewhere, was Frank Furness, one of those unruly creative prodigies for whom there will never be any rational explanation. His work, like that of many other Victorian designers, drew on a rich variety of historical details—mixing, sometimes in a single building, elements from the Assyrian and Saracenic to the Romanesque and Gothic, along with large helpings of the nineteenth-century French Classical Revival style called Néo-Grec. More remarkably, he celebrated industrial components by refusing to conceal steel I-beams and rivets even in genteel interiors like those of his Bryn Mawr Hotel of 1890 in Pennsylvania (now the private Baldwin School for girls), where his forthright detailing presaged the frank exposure of underlying structure by twentieth-century high-tech modernists.

After this long-neglected giant was finally appreciated once more—a crucial turning point was the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 1973 Furness retrospective—overenthusiastic fans began to attribute every quirky Victorian survival in southeastern Pennsylvania to Furness, in much the same way that there are purported to be at least twice as many Long Island houses by Stanford White as he actually created. But just a brief familiarization with Furness’s design vocabulary makes it easy to identify his work, which was as personal as a thumbprint.

This quality is owed to a strong inner logic that prevailed no matter how wild and unexpected his juxtapositions of external elements—the antithesis of the slapdash eclecticism and flabby assemblage that typified much Victorian architecture. When Furness borrowed a motif from another era or culture, he had an uncanny instinct for producing striking compositional effects from these offbeat choices, reaffirmed time after time during his peak years of the 1870s and 1880s. This is manifest in the scores of railway structures he executed during those decades: 125 buildings for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, more than thirty-five for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and a dozen for the Pennsylvania Railroad (in 1880 America’s biggest corporation).

It’s not that his train depots insistently shout Furness. Rather, these odd little caprices simply could not be by anyone else. They are part Swiss chalet, part cuckoo clock, part Queen Anne dollhouse, but nonetheless as tough as can be, never cute or sentimental, and a world apart from the perfunctory shelters at whistle stops across the continent built during the golden age of the railroad. In his 1878 essay “Hints to Designers,” Furness wrote, “A design without action is merely a mechanical affair that might be produced by a mere machine.” The best of his railway stations—which comprise some of the most ingenious variations on a single theme in all of modern architecture—are as full of propulsive energy as the steam locomotives that stopped at them.

There was also an implicit political aspect to the vigorous and stylistically unprecedented architecture produced by Furness and several of his like-minded local contemporaries. Those included such now forgotten figures as Angus S. Wade, who in his numerous Philadelphia hotels, apartment buildings, and private houses shared Furness’s preference for red brick, terra-cotta ornament, bold massing, and quirky grace notes such as turrets, oriels, Juliet balconies, and baldachins, although Wade’s busy concoctions never coalesced with the brilliance displayed time and again by the master of this mode.

Progressive post–Civil War Philadelphia architects and their patrons saw their efforts as a fresh start as much as the founders of the United States had in this, the country’s first capital, a century earlier. If the unified redbrick Georgian aesthetic that prevailed there during the early years of the nation spoke of Enlightenment values and a democratic spirit, then the strong, confident, and inclusive architecture of Furness and his followers proclaimed the principles of its makers just as clearly after slavery was finally expunged. Lewis Mumford perceived this decisive break with the past when in 1957 he described Furness’s Provident Life and Trust Company of 1876–1879 in Philadelphia, just a stone’s throw from the site of the republic’s creation, as “nothing less than a second Declaration of Independence.”

Advertisement

2.

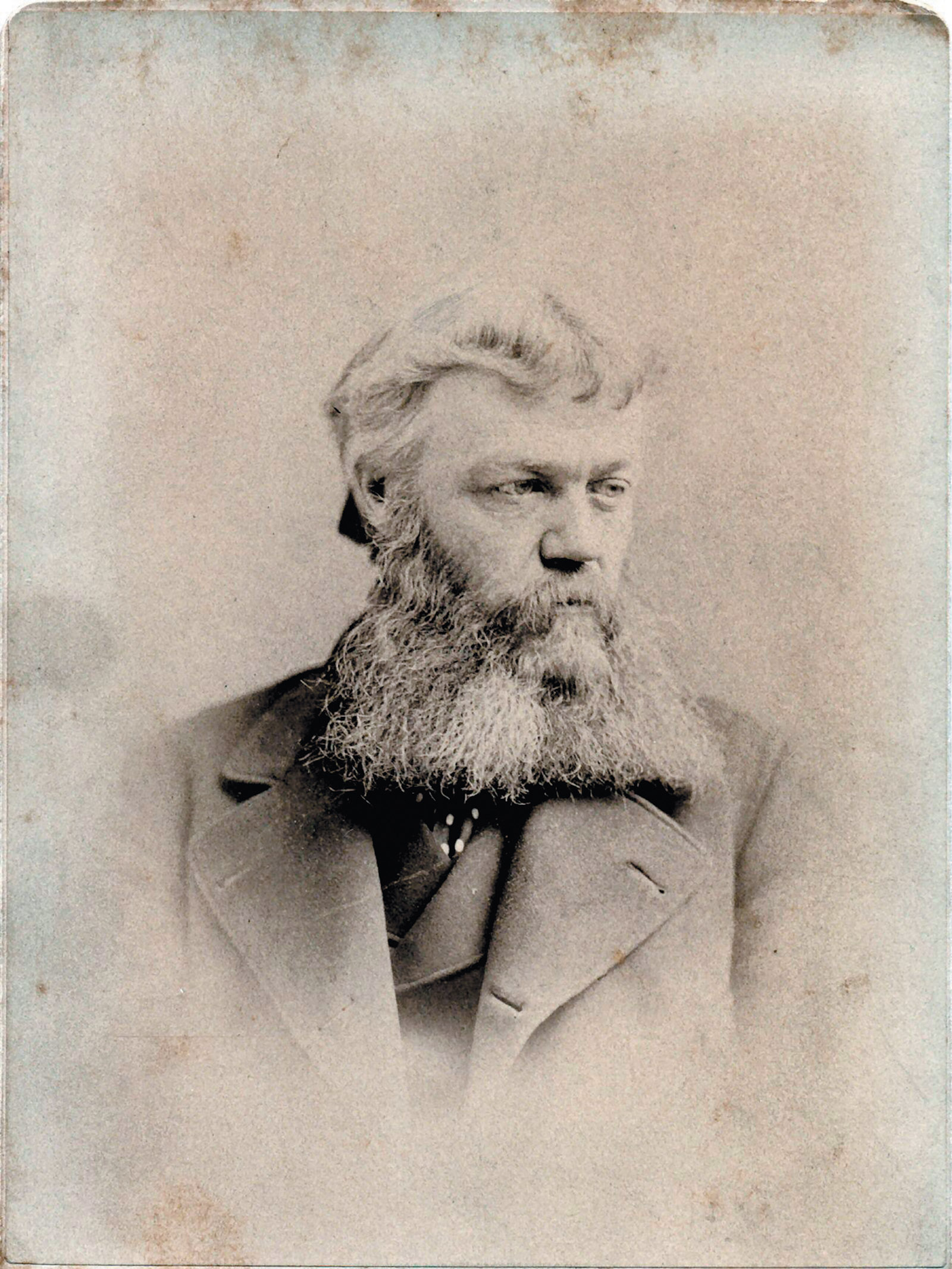

Frank Heyling Furness was born in 1839 in Philadelphia, where his Bostonian father, William Henry Furness, a prominent abolitionist and reformer, had moved more than a decade earlier to become minister of the First Unitarian Church. (According to family tradition, the name is pronounced furnace, not fur-NESS.) From nursery school onward, the elder Furness’s closest friend was Ralph Waldo Emerson, who visited him in Philadelphia through adulthood, and it takes no great leap of imagination to discern in the startling individuality of Furness’s architecture an embodiment of the Emersonian principles of confident nonconformity and rigorous self-reliance.

Although both Furness’s father and older brother went to Harvard, the teenage Frank showed no interest in following them. His persistent melancholy was noticed by the sympathetic Emerson, who encouraged the boy’s evident engagement with the visual world—manifest in his aptitude for drawing and interest in architecture—by giving him a stereoscope, the handheld device through which double-image photos could be viewed to simulate three-dimensional effects. At sixteen he was apprenticed to a local Philadelphia architect, and three years later he left for New York to enter the atelier of Richard Morris Hunt, the first American to be admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the world’s most prestigious architecture school. Furness intended to enroll there himself once he’d gained proficiency, but the Civil War soon intervened.

Pacifism was not one of the Transcendentalist traits young Furness absorbed from Emerson, and when hostilities broke out he enlisted in Rush’s Lancers, an elite Philadelphia company of mounted volunteers whose weapons were better suited to medieval jousts than industrialized conflict. The outfit saw combat at the Battle of Gettysburg, on a site now marked by Furness’s Sixth Regiment Cavalry Monument of 1888, a tapering octagonal granite shaft surrounded by eight bronze replicas of the unit’s lances. Eleven months later, at Trevilian Station, Virginia, described as “the Civil War’s greatest and bloodiest all-cavalry battle,” Furness, who had risen to the rank of captain, so distinguished himself for bravery that he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the only architect to ever receive that decoration.

He never abandoned his martial mien after he set up an architectural office back home with George Hewitt and John Fraser in 1866, a partnership that ended after only five years. Furness, who preferred being addressed as “Captain,” routinely hectored and cursed at his hirelings as if they were laggard conscripts, but he could also motivate them like a military leader inspiring his troops to victory. His most notable young employee, Louis Sullivan, withstood the barrage of verbal assaults well enough to observe his boss’s finer qualities. In The Autobiography of an Idea, he recalled the breathtaking facility with which Furness “made buildings out of his head,” and admitted that this intuitive artist held him “hypnotized, especially when he drew and swore at the same time.”

Furness’s irascible behavior was not confined to the workplace. His marriage was unhappy, and his sister bewailed “that cruel, cruel brother of ours.” Their father had been prone to bouts of depression, just as Frank was from adolescence onward, and it is likely that the architect had a form of what is now termed bipolar disorder, suggested by his sometimes extreme mood swings. Yet at reunions with his fellow Civil War veterans he typically was relaxed, garrulous, and jocular.

Furness was uncommonly prolific for a high-style architect—he designed more than seven hundred buildings—but his critical reputation subsided after his death in 1912, aged seventy-two. It was only the demolition of several of his most important buildings during the 1950s and 1960s, before the revulsion toward Victorian design abated, that prompted a widespread reappraisal of this American original. Scott Brown and Venturi were at the forefront of the successful campaign to save one of Furness’s principal masterworks, the University of Pennsylvania Library of 1888–1891, from being torn down (see illustration on page 46). This castellated composition, which resembles a redbrick armadillo, was about to meet the same fate suffered by several nearby Furness landmarks during an orgy of unconscionable destruction at the height of the postwar urban renewal craze.

Advertisement

A prime mover behind this stylistic purge was Edmund Bacon, executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970. A particular bugbear of Bacon’s was Furness’s so-called Chinese Wall, the two-story-high masonry-clad viaduct that carried trains into his majestic Broad Street Station of 1892–1893, a ten-story Victorian Gothic pile that incorporated a terminus hotel much like George Gilbert Scott’s imposing Midland Grand Hotel of 1868–1873 in London adjoining St. Pancras Station. There were two ways to bring trains into the heart of cities: below grade via tunnels or trenches, and above ground on trestles. Philadelphia opted for the latter, but by the mid-twentieth century its Chinese Wall (the epithet referred to the Great Wall of China) epitomized outmoded and obstructive urbanism.

During the 1930s construction of two modern railway depots nearby—30th Street Station for intercity trains transversing the Northeast Corridor, and Suburban Station for local commuters—made Broad Street Station redundant. The terminal, hotel, and viaduct were demolished in 1953 to make way for Penn Center, a sterile late–International Style city-within-a-city lacking the vivacity of New York’s Rockefeller Center. Even more destructive was Bacon’s simultaneous transformation of the area around Independence Hall, the former Pennsylvania State House where both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were signed.

In 1938 Roy F. Larson, a partner of the Beaux-Arts-trained Philadelphia architect Paul Philippe Cret (who taught Kahn at Penn), devised a plan to turn several densely built-up blocks north of Independence Hall into a French Baroque–style tapis vert more appropriate for Versailles than the humane scale of the area’s modest Georgian architectural survivors or William Penn’s foundational city layout of 1682, a grid symmetrically interspersed with intimate garden squares in the London manner. Under Bacon’s aegis, implementation of Larson’s scheme began in 1952, with 143 structures leveled to make way for the greensward. The newly exposed Independence Hall, dwarfed by the scale of the vacant quarter-mile-long expanse in front of it, was likened to a souvenir inkwell atop a huge office desk.

Several of Furness’s finest works were wrecked during the ensuing eastward extension of this newly designated Independence National Historical Park, which grew into a forty-five-acre L-shaped theme neighborhood where only Colonial-style buildings were retained, while any Victorian vestiges—seen as anachronistic eyesores—were expunged. Today such wanton waste seems unthinkable. One can easily envision Broad Street Station turned into a chic boutique hotel, the Chinese Wall behind it converted into a popular elevated park like New York’s High Line, and Furness’s banks and insurance companies near Independence Hall—alike in their tall, open, sky-lit interiors—remade into sought-after event venues.

In retrospect, the gutting of the best portions of nineteenth-century Philadelphia in service of heritage tourism and misguided notions of civic “progress” was nothing less than a cultural crime. Among the most tragic losses was Furness’s tiny but vibrant National Bank of the Republic of 1883–1884, which Venturi, in his Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), called “an almost insane short story of a castle on a city street.” Its needless obliteration is what now appears insane.

3.

Among Furness’s most ardent twentieth-century champions was the architectural historian Vincent Scully, who in his American Architecture and Urbanism (1969) accorded the forgotten master a far higher place in the canon than scholars of the preceding generation had. Those included Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who in 1936 wrote of Furness’s “bold vagaries” in much the same slighting tone that his contemporary Nikolaus Pevsner used to disparage Antoni Gaudí’s freeform flights of fancy in his Pioneers of the Modern Movement, published that same year.

The intractably unconventional Furness remains as difficult to assign a precise place in the lineage of Modernism as the Catalan maverick Gaudí, but Scully had no difficulty situating the Philadelphian among the master builders of this country, calling him “the first great architect in America after Jefferson and certainly the most original up to his time.” Just as there is no question about the dearth of architectural genius in the United States during the first three quarters of the nineteenth century, there could be no doubt about Furness’s breathtaking inventiveness and utter fearlessness, never more so than when his work was first exposed to a vast national public at the Centennial International Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia.

Among the several Furness works leveled to make way for Independence National Historic Park was his Provident Life and Trust Company, subject of a rapturous Scully riff that he often reiterated in his inimitably incantatory lectures. As he wrote:

[In what was] surely his grandest success, he appropriated one of the entrance pavilions of Viollet-le-Duc’s Château de Pièrrefonds, lifted it off the ground, and dropped it, as from a great height, upon a tough little building whose walls all compacted under the impact, arches fracturing in compression, while the roofs of the wings fell in upon the main mass and, most of all, the polished columns were driven like brass pistons into rupturing cylinders, screeching with heat. Inside, the high, narrow space was threatened as by a falling drill press. The whole building is (was, alas) a great machine looming out of technology’s archaic beginnings, a cast-iron marvel by Jules Verne, like those horrifically displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876…. The Provident Trust was…a paroxysm at once athletic and mechanical, of mass man hulking forward, a great golem of industrialism clanking away.

It is hard to imagine that this unforgettably vivid evocation did not inform the main thesis of the brilliant new study Frank Furness: Architecture in the Age of the Great Machines, by the architectural and cultural historian George E. Thomas, who contends that the unprecedented mechanization of the Victorian Era was central to the advance of architecture even while historicizing motifs were still very much in use. Thomas goes on to specify how the flourishing engineering culture of post–Civil War Philadelphia produced machines and tools with such high-precision tolerances that, as the extensive presentations at the great exposition would confirm, they became the envy of the industrial world, with even German craftsmen shamed by the comparative shoddiness of the examples they brought to impress American upstarts.

4.

Furness’s participation in the Centennial Exhibition was limited to his inexplicably Islamic-style display stand for Brazil inside the Main Exhibition Hall. (That country’s indigenous and Portuguese Colonial architecture were apparently thought unacceptable models, and perhaps it was felt that one form of exoticism was as good as another.) But visitors to Philadelphia also would have been able to see a spectacular array of new buildings by Furness all around town, including several handsome churches, townhouses, and financial institutions, among them the Centennial National Bank, directly across from the West Philadelphia railroad station where fairgoers arrived. And next to the exhibition grounds in Fairmount Park (then as now the nation’s largest urban green space) stood Furness’s fanciful structures for the Philadelphia Zoological Gardens, with a pair of fairytale-like gatehouses (still standing), the fittingly powerful Elephant House, and a romantic verandah-wrapped restaurant (both now gone).

On the city’s North Broad Street soared the Moorish domed steeple of Furness’s Rodef Shalom Synagogue of 1868–1869 (since demolished), which was embellished with decorative motifs from the Alhambra as reproduced in the British architect Owen Jones’s universally consulted pattern book The Grammar of Ornament (1856). This commission went to Furness’s firm thanks to a prominent congregant, the education reformer and philanthropist Rebecca Gratz, who admired his social activist father. (She is also believed to have been the prototype for Rebecca, the Jewish heroine of Ivanhoe, whose author, Walter Scott, likely heard of this beautiful, virtuous Philadelphian through their mutual friend Washington Irving.)

Even though Furness was not Jewish (unlike Louis Kahn, who would receive numerous commissions from local coreligionists decades later), he maintained close relations with the city’s Jewish community and went on to erect the Jewish Hospital of 1871–1873, the Home for Aged and Infirm Israelites of 1888, and the Mount Sinai Cemetery Mortuary Chapel of 1891–1892. Thus Philadelphia Jews could pass through all their major life events in a Furness structure.

Not far from the site of his sumptuous shul stands one of his most conspicuous public efforts, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts of 1871–1876 (see illustration on page 43), with its street front in a heady farrago of materials, colors, and textures—red brick, purple terra-cotta, figuratively carved beige sandstone, roughhewn brownstone, and polished pink granite. It remains arguably the liveliest façade in the United States, the electrified wonders of Las Vegas and Times Square notwithstanding. This dazzling building, with deeply hued and richly ornamented interiors as extraordinary as its exterior, is the subject of First Modern, an excellent monograph by George E. Thomas, who collaborated with James F. O’Gorman on the 1973 exhibition catalog and was an author (with Michael J. Lewis and Jeffrey A. Cohen) of the indispensable catalogue raisonné and reference Frank Furness: The Complete Works (1991). With these two latest publications, Thomas further secures his reputation as our leading authority on the architect, and places his subject squarely in a social setting too often missing when researchers obsess over stylistic and formal matters.

For example, Thomas demonstrates that the designs of Furness’s train stations were far from whimsical. They were dictated above all by the practical requirements of stationmasters who were expected to live in the depots, a security precaution that anticipated by a century Jane Jacobs’s neighborhood safety principle of “eyes on the street.” Clear sightlines were needed toward oncoming trains in both directions, whatever electrical signals might also be in place, so a high vantage point was always a necessity. Despite their picturesque qualities, these railway outposts were carefully calibrated in service of a form of transportation that had been invented only a few decades earlier.

How ironic that Furness, once so well attuned to the tenor of his times, would become professionally stranded after the radical shift in taste accelerated by the next great American fair after the Philadelphia Centennial—the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Sullivan predicted that the overblown Beaux-Arts fantasyland of the Chicago fair would set architecture back by fifty years, and he was not far off the mark. Despite the number of excellent Neoclassical buildings that proliferated on the American cityscape during the following decades as a direct result of the Columbian Exposition, that conservative trend undermined the convincingly contemporary architecture that Furness, Sullivan, and other freethinking pioneers had been offering as a vital alternative to Classical Revival bombast.

After 1900, Furness’s dominance over his practice dribbled away, and his younger partners effectively sidelined him to give clients what they wanted. Today, half a century after the rediscovery of the fiery Furness, the impassioned advocacy of George Thomas continues to reveal the genius of this magnificent misfit.

-

1

See my “A Mystic Monumentality,” The New York Review, June 22, 2017. ↩

- 2