Under certain circumstances, the question of whether a particular string of letters constitutes a word can assume a momentary prominence, with money or honor on the line. Passionate squabbles can erupt over a game of Scrabble or over how Jeff Bezos asserts his right to privacy. In his February online post accusing the National Enquirer of blackmail, the billionaire founder of Amazon used the doubtful word “complexifier,” twice, as in, “My ownership of the Washington Post is a complexifier for me.” Commentators were quick to point out that “complexifier” is indeed a word, although a verb, in French.1 Poor Bezos, they seemed to imply, deserved some linguistic latitude for having employed a combination of letters that constituted a word somewhere, even if not in Los Angeles or London, as opposed to, say, “covfefe.” And who decides, anyway?

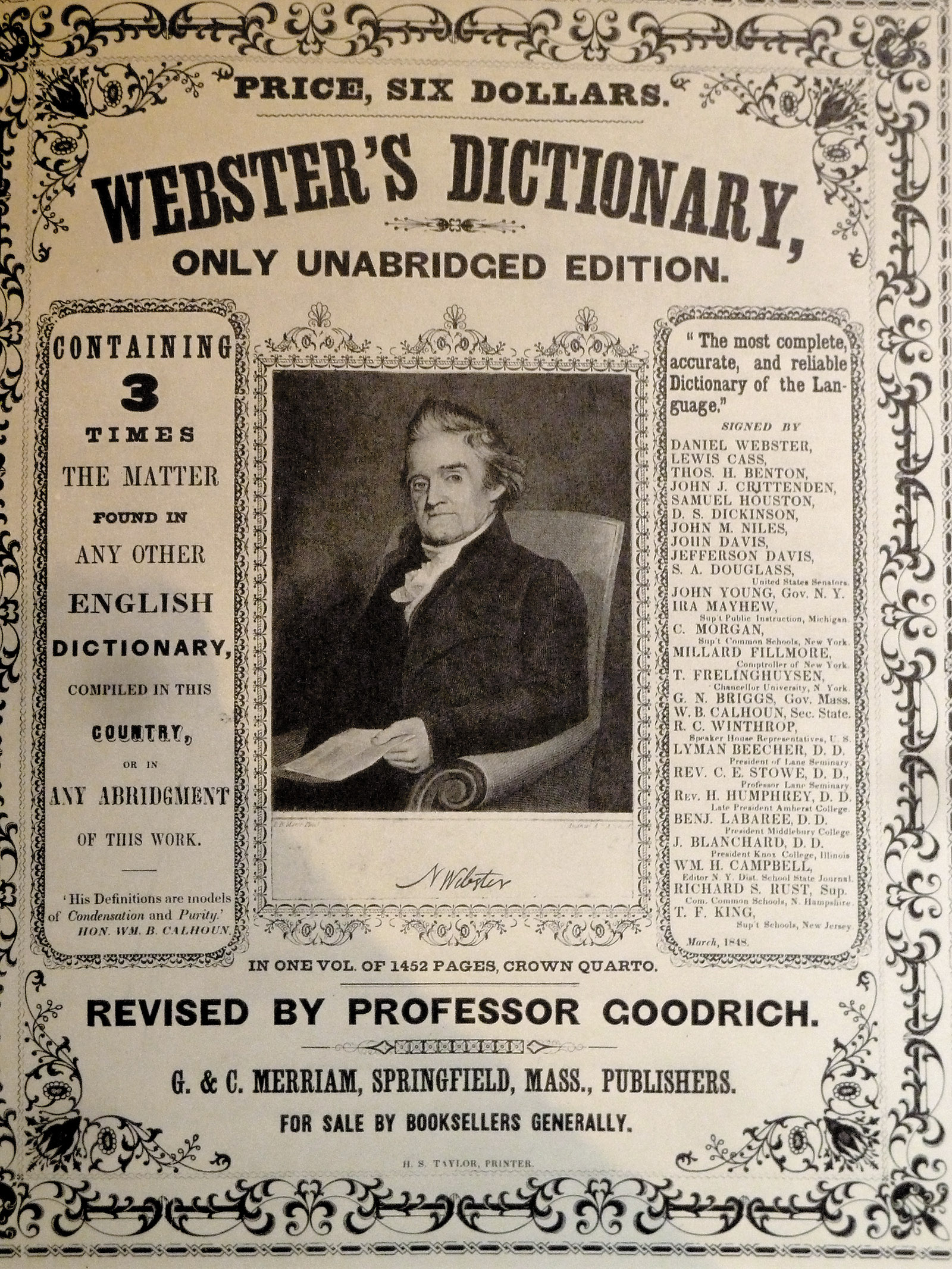

The dictionary, of course, or “Webster,” as students will still say when admonished to define their terms, though which Webster—Daniel, Noah, or perhaps Merriam—few could say. The story of how so many dictionaries in America came to be known, generically, as Webster’s—a triumph of branding if there ever was one—is among the intriguing lore gathered in Peter Martin’s engaging and informative, if at times a little cluttered, The Dictionary Wars, with forays into copyright law, educational policy, religious revivalism, and other pressures on the verbal life of the nation.

The dictionary wars that interest Martin played out during the middle of the nineteenth century. They are to be distinguished from the spirited controversies, sometimes called the usage wars, surrounding the publication in 1961 of Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language.2 Webster’s Third was felt by many critics to be unduly permissive, sacrificing authority to the vagaries of usage. “A dictionary should have no traffic with…artificial notions of correctness or superiority,” its editor proclaimed. “It should be descriptive and not prescriptive.” If ordinary speakers insisted on confusing “disinterested” with “uninterested,” let them be synonyms, Webster’s Third ruled. And if those same speakers used dirty words, let those words in, “with the exception,” as Dwight Macdonald drily noted, “of perhaps the most important one.”

Kindred points of contention, as Martin notes, had bedeviled dueling dictionaries a hundred years earlier. Given the preponderance of the Webster name, one might think that Noah Webster—whose landmark An American Dictionary of the English Language (Webster’s First) was published in 1828 in two huge volumes—was the unquestionable victor in the dictionary wars, as they were already referred to at the time. Similarly, one might conclude that Joseph Worcester, the largely forgotten Harvard-based lexicographer who was Webster’s most formidable rival, was the conspicuous loser. But the story is more complicated than that, with players both scrupulous and shameless enlivening the narrative.

Webster, who died in 1843 at the age of eighty-four, was gone by the time that, a decade later, the dictionary wars raged most intensely. The dictionaries in use today owe far more to Worcester, a brilliant, levelheaded, and innovative lexicographer, than to the hotheaded pioneer Webster, who left little more to posterity than his name. And yet the questions Webster wrestled with—to what degree a dictionary should be a moral guide, what prominence should be accorded to distinctly American words and phrases, how offensive words should be treated, how much respect should be accorded to regional, ethnic, or other variations in usage—remain with us to this day.

Born in 1758 into a poor farming family in rural Connecticut, Noah Webster was a bookish child whose father mortgaged the family farm to pay his son’s expenses at Yale. He enrolled in 1774, not quite sixteen, on the eve of the American Revolution. Timothy Dwight, later a notable president of the college, told the graduating class in 1776 that they should be “concerned in laying the foundations of American greatness.” After Yale, Webster failed as a lawyer and a schoolmaster, and cast about for others to blame. Frustrated with British guides to teaching reading, which he considered effete and overly concerned with classical models, he had an astonishing success as the author of The American Spelling Book, one of the best-selling books in American history. “American” was the key word in the title; Webster believed that American English, already distinct in his view, would eventually be as different from British English as Portuguese from Spanish. With his “Blue Back Speller,” he hoped to hasten that evolution. Soon he added a grammar, a reader, and, in 1806, his first stab at a dictionary, a compact school edition, in preparation for his comprehensive magnum opus.

For Webster, an American dictionary was a continuation of the American Revolution by other means. Just as the colonies had suffered under the tyrannical reign of King George III, Webster felt that the heavy hand of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language—published in 1755 and still regarded, fifty years later, as the authoritative guide to proper usage—impeded everything Americans said and wrote.

Advertisement

Johnson had snidely coined the phrase “American dialect” to mean “a tract [trace] of corruption to which every language widely diffused must always be exposed.” Jefferson’s use of a seemingly harmless word like “belittle” caused a small furor in England when he wrote, “He believes that nature belittles her productions on this side of the Atlantic.” “It may be an elegant [expression] in Virginia,” sniffed one commentator, claiming he could only “guess at its meaning.”3 Outlandish words like “hornswoggle,” “hunky-dory,” and “skedaddle” were beyond the pale. “Now is the time, and this the country,” Webster proclaimed in 1789, almost forty years before he completed his dictionary. “Let us then seize the present moment, and establish a national language as well as a national government.”

Like many self-styled revolutionaries, Webster—“cranky, irritable, and arrogant,” according to Martin—combined two tendencies that quickly came into conflict. Against the foppish English of the British court and theater (which he thought, mistakenly, that Johnson had revered), Webster wished to affirm the language as commonly spoken in American towns and villages, with his explicit standard “the common unadulterated pronunciation of the New England gentleman.” He anticipated Webster’s Third in calling for description over prescription: “The lexicographer’s business is solely to collect, arrange and define the words that usage presents to his hands. He has no right to proscribe words; he is to present them as they are.”

At the same time, in a utopian gesture typical of the founders of nations, Webster proposed a radical simplification of spelling.4 Webster’s war on silent letters yielded a few victories, like “color” (for “colour”) and “public” (for “publick”), but he could not persuade Americans to adopt “bred” or “thum,” or more radical orthographic realignments like “masheen” or “wimmen.” Webster was the target of vigorous mockery for such proposals; during the long gestation of his dictionary, as his political views curdled, he abandoned almost all of them.

Webster departed in other ways from his stated aim “solely to collect, arrange and define the words that usage presents to his hands.” He had always been a prig, more prone to policing language than celebrating its abundance and vitality. He was appalled that Johnson had included words like “sucked, fornication, and whore”—verbal excrescences that a New England gentleman would never, apparently, resort to—and he resolutely excluded “fart” and “turd.” These reactionary tendencies were exacerbated by Webster’s religious conversion in 1808, amid the revivalist movement known as the Second Great Awakening. Webster’s dictionary was henceforth made to do double duty: to honor the linguistic needs of the young nation as well as the Lord above. Marriage, according to his definition, was “instituted by God himself for the purpose of preventing the promiscuous intercourse of the sexes.” In 1833 Webster published an edition of the Bible similarly purged of “language which cannot be uttered in company without a violation of decorum or the rules of good breeding.” In Webster’s scrubbed scripture, “sucked” yielded to “nursed”; a “whore” became a “lewd woman.”

Financial straits led Webster to leave New Haven in 1812 for cheaper lodgings in the village of Amherst, Massachusetts, a Calvinist community consonant with his own newfound piety. In a spacious room of his large house on Main Street, which he described, absurdly, as a “humble cottage in the country,” he set up a huge round table, where he could lay out his sources as he completed his dictionary. He allowed himself, for groundwork, a long detour in pursuit of fanciful etymologies, wasting years on the quixotic pursuit of a pre-Babel ur-language, even as he ignored German research on Indo-European roots. Along the way, he developed an interesting theory that verbs, not nouns, were the origin of language: “Motion, action, is, beyond all controversy, the principal source of words.”

Martin mentions in passing that Webster, during his decade in Amherst, helped to establish Amherst College; buried in his footnotes is the interesting fact that another founder was Emily Dickinson’s grandfather. The college and the dictionary had similar aims: to maintain religious orthodoxy, serving as bulwarks against the sinister, liberalizing influences of Unitarian Harvard, which opposed the new college—with its stated mission of “evangelizing the world by the classical education of indigent young men of piety and talents”—as “a priest factory.”

Emily Dickinson, whose father and brother served as treasurers for Amherst College, was born and died in a house down Main Street from Webster’s. She attended Amherst Academy, for which Webster served as a trustee; among her classmates was one of Webster’s granddaughters. Describing her apprenticeship as a young poet, Dickinson, a wayward speller and adventurous punctuator, once told her literary adviser Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “For several years, my Lexicon—was my only companion.”5 Her poetry, with its “definition poems,” departs sharply from Webster’s pious constraints. Hope, for Webster, meant “confidence in a future event; the highest degree of well founded expectation of good; as a hope founded on God’s gracious promises.” Dickinson, who once wrote that she kept the Sabbath “staying at Home—/With a Bobolink for a Chorister,” adopted a more secular and emotionally intense definition: “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers—/That perches in the soul—/And sings the tune without the words—/And never stops—at all.”

Advertisement

Like Samuel Johnson, Webster worked alone. Johnson’s method of collecting words for his dictionary was primarily literary; he read poetry and essays, Shakespeare and the Bible, writing down on slips of paper passages that seemed notable for the use of particular words, which were then alphabetized for later use.6 Webster had comparatively little use for literature, nor, in the 1820s, did he have all that much nationally to choose from. The major writers of the time were Washington Irving and William Cullen Bryant, whose subject matter was more American than their diction, and James Fenimore Cooper, who mingled Indian words with a narrative style borrowed from Sir Walter Scott.

Webster made no field trips to record American usage, and seems to have made little use of the popular amateur fad of word-collecting. Just as Audubon had combed the American outback in search of exotic birds, collectors amassed thousands of new words, often technical in nature, and sometimes sold them for a profit. William Allen, a former president of Bowdoin and Dartmouth, assembled 10,000 words and offered them to a dictionary publisher at the price of $10 per hundred words. While Webster introduced a few American words like “skunk” and “squash,” “the sprinkling of Americanisms” in his dictionary, Martin notes, were “few in number.” Despite his hostility to his great precursor, Webster borrowed fully a third of his definitions from Johnson, many of them verbatim and others with only a word or two altered. His major sources, in addition to previous dictionaries, seem to have been his friends and his own experience, resulting in a dictionary that is less American than New England in character, as in his definition of “sauce”: “In New England culinary vegetables and roots eaten with flesh. Sauce consisting of stewed apples is a great article in some parts of New England; but cranberries make the most delicious sauce.”

Webster’s 1828 dictionary was widely greeted as some kind of masterpiece, but it was too cumbersome for convenient use in schools, and an abridgment was thought necessary. It was undertaken in part by Webster’s erudite son-in-law Chauncey Goodrich, a professor of rhetoric at Yale. Joseph Worcester, a Yale graduate who was working on a dictionary of his own, was enlisted as his collaborator. A skilled hand in reference works and familiar, unlike Webster, with the latest research on etymology, Worcester did an expert job on the abridgment. And yet his work opened him up to the baseless charge—the central issue of the resulting dictionary wars—that he subsequently stole from Webster to bolster his own dictionaries.

A largely forgotten figure in American letters, Worcester comes across, in Martin’s telling, as a far more attractive figure than Webster, moderate where Webster was vehement, liberal-minded in contrast with Webster’s narrow religiosity. Raised on a farm in New Hampshire, he graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover before entering Yale. Later, he settled in Salem, where one of his students was Nathaniel Hawthorne. In 1819, intent on a literary career, he moved to Cambridge to be near the libraries of Harvard. He shared a house with Longfellow, who described him as “a tall, lean, crooked man.” Worcester published lucrative and much admired reference works in history and geography. His shy and pensive temperament, unlike Webster’s, won him many admirers. In an affectionate tribute, Dickinson’s friend Higginson described Worcester as “a slumbering volcano of facts and statistics.”

On assuming the task of abridging Webster’s sprawling dictionary, Worcester discovered that more than just judicious excisions were called for. Webster’s etymologies, the dubious fruit of “ten long years of fantastic conjectures that virtually froze his progress,” as Martin puts it, needed to be replaced. The more extreme of the proposed reforms in spelling had to be scrapped. Readers could not be persuaded to sacrifice “bridegroom” for “bridegoom” even if, as Webster insisted, the word was originally “a compound of bride and gum, guma, a man.” Webster was often praised for his definitions, but Worcester and Goodrich pruned them of Webster’s religious emphasis.

Two ambitious brothers, George and Charles Merriam, who ran a printing press in Springfield, Massachusetts, had taken a particular interest in Webster’s work. They bought unsold sheets of the 1828 dictionary; after Webster’s death in 1843, they secured the rights, from Goodrich and other heirs, to publish any future revisions of the work. The Merriams recognized, as Martin notes, that Webster was “a name they could exploit,” and were determined to protect the Webster brand at any cost. Their larger aim was to quarry Webster’s 1828 magnum opus for an authoritative dictionary that would corner the American market once and for all.

When Worcester’s own Universal and Critical Dictionary of the English Language, a shorter version intended for school use, appeared in 1846 to wide acclaim, the Merriams recognized in Worcester’s careful work a threat to their own plans to monopolize the dictionary market. The brothers immediately resorted to a scurrilous campaign to discredit Worcester. In a series of pamphlets and articles, they claimed that he had plagiarized from Webster. The so-called dictionary wars had their origins in this brazen and baseless accusation.

Worcester’s comprehensive dictionary of 1860, an enormous undertaking widely admired in both America and Britain, seemed to put an end to the competition. But the Merriams were undeterred. Hiring a team of scholars, including half of Yale’s twenty faculty members, they completed, at breakneck speed, An American Dictionary of the English Language by Noah Webster, LL.D. in 1864. Having accused Worcester of theft, the Merriams saw no conflict in stealing from him in turn. By the time the team was done with its work, there was virtually nothing left of Webster in Webster’s dictionary, but there was a great deal of Worcester. “Much, or most, of what [Webster] stood for as a lexicographer,” Martin concludes, “except for a handful of his spelling reforms and his reputation as a definer of words, vanished in the 1864 edition.” The 1886 edition quietly dropped Webster’s signature adjective “American” from the title, Webster’s Complete Dictionary of the English Language, thus dealing a deathblow to his lifelong dream of codifying a separate American language.

Martin characterizes the Merriam brothers as “ruthless,” a word defined in the online Merriam-Webster Dictionary (“since 1828,” according to the website) as “having no pity: merciless, cruel.” That seems a generous assessment of what they did to Worcester and other rivals. Their lasting contribution to lexicography, perhaps, was their realization that the job of writing a dictionary was too big for one person. There were simply too many pockets of verbal invention—the workplace, the laboratory, the hospital, the barroom—for a single researcher to master. And more importantly, the language was changing too rapidly. With their constant revisions, today’s online dictionaries seek to capture this mutability.

One might have thought that Noah Webster, living through a period of revolutionary change, both political and cultural, would have felt this linguistic dynamism most acutely. But for all his praise of motion and his love of verbs, he was in love with fixity. He wanted to establish meanings once and for all, to arrest pronunciation, to impose uniform spelling. It was Johnson, whom Webster took every opportunity to attack, who had the stronger sense of the mutability of language. In his marvelous, moody preface to his great dictionary, Johnson insisted at every turn on dynamism. After noting how difficult it was to trace the serpentine twists and turns of ordinary verbs such as “put” or “get” through “the maze of variation,” he remarked:

It must be remembered, that while our language is yet living, and variable by the caprice of every one that speaks it, these words are hourly shifting their relations, and can no more be ascertained in a dictionary, than a grove, in the agitation of a storm, can be accurately delineated from its picture [i.e., reflection] in the water.

It is difficult to imagine a more noble expression—in its democratic allowance for linguistic variation by everyone who speaks a language, its exquisite sense of hourly shifts in verbal meaning, and its great metaphor of words as trees agitated by a storm—of the ultimate futility of the dictionary writer’s task.

-

1

Although “very rare,” according to The Oxford English Dictionary, the English word “complexify” has been around since at least 1830; “complexifier” is in current use as a technical term in quantum physics. ↩

-

2

See David Foster Wallace, “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage,” Harper’s, April 2001. ↩

-

3

Jefferson used the word in his widely disseminated Notes on the State of Virginia (London, 1787), objecting to what he considered the public slighting of the New World by the French naturalist Buffon. English readers may have felt that Jefferson, in praising American grandeur, was belittling them. ↩

-

4

While he seemed a democratic populist in his approach to language, he was fiercely reactionary in much else. A passionate Federalist, he was wary of democratic rule, hostile to immigration, and supported a strong central government. See, for example, Joseph J. Ellis, After the Revolution: Profiles of Early American Culture (Norton, 1979), and Jill Lepore, “Noah’s Mark: Webster and the Original Dictionary Wars,” The New Yorker, November 6, 2006. Ellis characterizes the great dictionary as “the life statement of a disillusioned republican who hoped to shape the language and therefore the values of subsequent generations in ways that countered the emerging belief in social equality, individual autonomy, and personal freedom,” p. 211. ↩

-

5

See Cristanne Miller’s Emily Dickinson: A Poet’s Grammar (Harvard University Press, 1987) for an interesting analysis of Webster’s likely influence on Dickinson, including his emphasis on verbs, p. 154. ↩

-

6

See Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age (Yale University Press, 2019), pp. 42–46; reviewed in these pages by Jenny Uglow, May 23, 2019. ↩