1.

Books about impeachment began appearing almost as soon as Donald Trump took the oath of office. One of the earliest, Impeachment: A Citizen’s Guide by Cass R. Sunstein, scrupulously avoided mentioning the president by name.1 But Sunstein, a Harvard law professor, set out twenty-one hypothetical scenarios, grouping them as “easy cases” for impeachment, “easy cases” against, and “harder cases,” some strikingly prescient, that could go either way.

Since then, the flood of impeachment books has shown no sign of letting up. Looming over all of them is the Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election—the Mueller Report (though in redacted form). In two volumes totaling 448 pages, it is not formally a book, although it quickly attained best-seller status on Amazon as an instant paperback produced by The Washington Post, with added commentary by two Post reporters.2

When I first read the Mueller Report, in several sittings shortly after its public release on April 18, I assumed that it would become the book against which all the others on impeachment would be judged. The writing is clear and jargon-free, even riveting in its deadpan just-the-facts narrative. The 182-page volume 2, which analyzes thirty-eight separate incidents as potential obstructions of justice (one is completely blacked out as “HOM—Harm to Ongoing Matter”), reads like a cross between Wolf Hall and Richard III, depicting the White House under the shadow of the Russia investigation in a constant state of crisis, as the president’s top aides struggle to both serve their master and save their own skins—not only from his wrath but from the potential legal consequences of carrying out his orders. It is Trumpian reality television come startlingly to life.

Most accounts of the report, understandably focused on the conclusions—obstruction? indictable? impeachable?—have omitted the detail needed to fully grasp both the madness in the White House and the sheer energy these aides had to expend to keep the presidential engine from jumping the track. From the report itself, we learn in one example of potential obstruction of justice that on June 19, 2017, Trump instructed Corey Lewandowski, his former campaign manager, to tell Attorney General Jeff Sessions to give a speech denouncing the special counsel’s investigation. Lewandowski was at the time a private citizen—not, one would think, someone empowered to give orders to the attorney general.

Sessions, to the president’s lasting fury, had recused himself from the Russia investigation, which Trump saw as no obstacle to his further instruction to Lewandowski: tell Sessions to meet with the special counsel and order him to limit his inquiry to future election interference—implicitly shutting down the investigation into Russian interference on behalf of the Trump campaign in 2016. “Write this down,” the president told Lewandowski, who took notes on what Sessions was to say in the speech:

I know that I recused myself from certain things having to do with specific areas. But our POTUS…is being treated very unfairly. He shouldn’t have a Special Prosecutor/ Counsel b/c he hasn’t done anything wrong. I was on the campaign w/ him for nine months, there were no Russians involved with him. I know it for a fact b/c I was there. He didn’t do anything wrong except he ran the greatest campaign in American history…. Now a group of people want to subvert the Constitution of the United States. I am going to meet with the Special Prosecutor to explain this is very unfair and let the Special Prosecutor move forward with investigating election meddling for future elections so that nothing can happen in future elections….

The report then continues:

The President said that if Sessions delivered that statement he would be the “most popular guy in the country.” Lewandowski told the President he understood what the President wanted Sessions to do.

But Lewandowski did not deliver this message to the attorney general. After a month had gone by and Trump asked him whether he had, Lewandowski ran into Rick Dearborn, a deputy White House chief of staff and former aide to Sessions when Sessions was in the Senate. Lewandowski handed Dearborn a typewritten version of the speech the president had dictated. According to the report:

The message “definitely raised an eyebrow” for Dearborn, and he recalled not wanting to ask where it came from or think further about doing anything with it. Dearborn also said that being asked to serve as a messenger to Sessions made him uncomfortable. He recalled later telling Lewandowski that he had handled the situation, but he did not actually follow through with delivering the message to Sessions, and he did not keep a copy of the typewritten notes Lewandowski had given him.

A second example from the report of potential obstruction of justice, involving Donald McGahn, then the White House counsel, began two days before the president’s demand of Lewandowski. The report’s uninflected narrative—not an adjective or characterization in sight—actually serves to heighten the drama inherent in this scene. It’s as if we are inside the White House counsel’s head, fighting panic, looking for a way out, and deciding that this time, there wasn’t one. It is worth quoting from this section at length:

Advertisement

On Saturday, June 17, 2017, the President called McGahn and directed him to have the Special Counsel removed. McGahn was at home and the President was at Camp David. In interviews with this Office, McGahn recalled that the President called him at home twice and on both occasions directed him to call [Rod Rosenstein, the deputy attorney general who, following Sessions’s recusal, became acting attorney general for matters relating to the Russia investigation] and say that Mueller had conflicts that precluded him from serving as Special Counsel.

On the first call, McGahn recalled that the President said something like, “You gotta do this. You gotta call Rod.” McGahn said he told the President that he would see what he could do. McGahn was perturbed by the call and did not intend to act on the request. He and other advisors believed the asserted conflicts were “silly” and “not real,” and they had previously communicated that view to the President. McGahn also had made clear to the President that the White House Counsel’s Office should not be involved in any effort to press the issue of conflicts. McGahn was concerned about having any role in asking the Acting Attorney General to fire the Special Counsel because he had grown up in the Reagan era and wanted to be more like Judge Robert Bork and not “Saturday Night Massacre Bork.” McGahn considered the President’s request to be an inflection point and he wanted to hit the brakes.

When the President called McGahn a second time to follow up on the order to call the Department of Justice, McGahn recalled that the President was more direct, saying something like, “Call Rod, tell Rod that Mueller has conflicts and can’t be the Special Counsel.” McGahn recalled the President telling him “Mueller has to go” and “Call me back when you do it.” McGahn understood the President to be saying that the Special Counsel had to be removed by Rosenstein. To end the conversation with the President, McGahn left the President with the impression that McGahn would call Rosenstein. McGahn recalled that he had already said no to the President’s request and he was worn down, so he just wanted to get off the phone.

McGahn recalled feeling trapped because he did not plan to follow the President’s directive but did not know what he would say the next time the President called. McGahn decided he had to resign. He called his personal lawyer and then called his chief of staff, Annie Donaldson, to inform her of his decision. [Donaldson was subpoenaed by the House Judiciary Committee on May 21.] He then drove to the office to pack his belongings and submit his resignation letter. Donaldson recalled that McGahn told her the President had called and demanded he contact the Department of Justice and that the President wanted him to do something that McGahn did not want to do. McGahn told Donaldson that the President had called at least twice and in one of the calls asked “have you done it?” McGahn did not tell Donaldson the specifics of the President’s request because he was consciously trying not to involve her in the investigation, but Donaldson inferred that the President’s directive was related to the Russia investigation. Donaldson prepared to resign along with McGahn.

That evening, McGahn called both [Reince Priebus, White House chief of staff] and [Stephen Bannon, adviser to the president] and told them that he intended to resign. McGahn recalled that, after speaking with his attorney and given the nature of the President’s request, he decided not to share details of the President’s request with other White House staff. Priebus recalled that McGahn said that the President had asked him to “do crazy shit,” but he thought McGahn did not tell him the specifics of the President’s request because McGahn was trying to protect Priebus from what he did not need to know. Priebus and Bannon both urged McGahn not to quit, and McGahn ultimately returned to work that Monday and remained in his position. He had not told the President directly that he planned to resign, and when they next saw each other the President did not ask McGahn whether he had followed through with calling Rosenstein.

There, revealed in all its granular glory, is the state of our democracy today. The question is, what happens next? McGahn eventually did resign as White House counsel in October 2018 after having rebuffed, The New York Times reported on May 10, two requests from White House officials to declare publicly that in his view the president had not obstructed justice. On May 7 the president ordered him not to comply with a subpoena from the House Judiciary Committee to produce White House records related to the Mueller investigation. This, along with the struggle between the House of Representatives and the Trump administration over whether Congress can get access to the full unredacted report, brings me back to my expectation that the Mueller Report would be the ultimate impeachment book. It won’t be—and not only because it draws no concrete conclusions from the mass of facts it presents. It won’t be because it quickly turned out that for all its length, it is proving to be little more than a chapter, albeit an important one, in an ongoing war for control of the narrative of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Advertisement

Sessions’s successor as attorney general, William Barr, recognized immediately the importance of controlling the narrative. He began with a misleading letter summarizing the report to Congress on March 24, two days after he received it and weeks before the public would see the redacted version, and continued with that misleading stance at a press conference hours before the report’s public release on April 18. Because volume 1 of the report states conclusively that there was not sufficient evidence to charge the Trump campaign with having criminally conspired with the Russians, Barr’s focus was on the strikingly ambiguous volume 2, which lays out the evidence of potential obstructions of justice. Although his letter accurately quoted the report’s conclusion—“while this report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him”—the attorney general went on to declare:

The report identifies no actions that, in our judgment, constitute obstructive conduct, had a nexus to a pending or contemplated proceeding, and were done with corrupt intent, each of which, under the Department’s principles of federal prosecution guiding charging decisions, would need to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt to establish an obstruction-of-justice offense.

This was the three-part test to which Robert Mueller and his team subjected each of the incidents the report describes: Did the conduct qualify as an “obstructive act” under the relevant federal statutes? Did it have a connection to an official proceeding—Mueller’s investigation or others? Did the president have a corrupt intent? The report then analyzes most of the incidents, including the two I’ve described here, in highly suggestive terms with which the attorney general’s characterization is completely at odds. The Mueller Report is, as David Cole wrote in these pages, “an indictment in all but name.”3

Within days, Mueller sent Barr a letter objecting that in his letter to Congress, he “did not fully capture the context, nature, and substance of this Office’s work and conclusions.” But Mueller’s objections didn’t become public for nearly a month. By then, the damage had been done. By maintaining his stance as a principled professional whose mandate was to lay out the facts rather than render a prosecutorial judgment, Mueller lost control of the narrative. “Democrats Largely Give Up on Impeachment in Wake of Mueller Report,” The Washington Post reported on March 25. Neither the public nor members of Congress had yet seen any version of the report. All they had was Barr’s letter and the president’s triumphant tweets of “NO COLLUSION!” The Post’s judgment of the Democrats’ mood was, as of that moment, undoubtedly accurate. But as the weeks have passed and the president’s defiance of the House of Representatives has escalated, all that’s clear is that, as Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in early May, the country is on the precipice of a constitutional crisis.

On May 29, anticipation was intense as word spread that the special counsel would make his first in-person public statement in the two years since his appointment. The low-key, precisely delivered nine and a half minutes of his speech were classic Mueller: the investigation was now formally closed; he was resigning as a Justice Department employee; and if he were to testify before Congress, he would not elaborate on anything in the report. “We chose those words carefully and the work speaks for itself,” he explained.

His reiteration of some of those carefully chosen words left some wondering whether they were hearing a simple summary or a hidden message: “If we had confidence that the president did not commit a crime, we would have said so,” he said. “The Constitution requires a process other than the criminal justice system to formally accuse a sitting president of wrongdoing.” Was this an explanation, or an invitation? Representative Justin Amash of Michigan, the only Republican to have called for the president’s impeachment, took it as the latter. “The ball is in our court, Congress,” he tweeted within moments after Mueller left the lectern.

2.

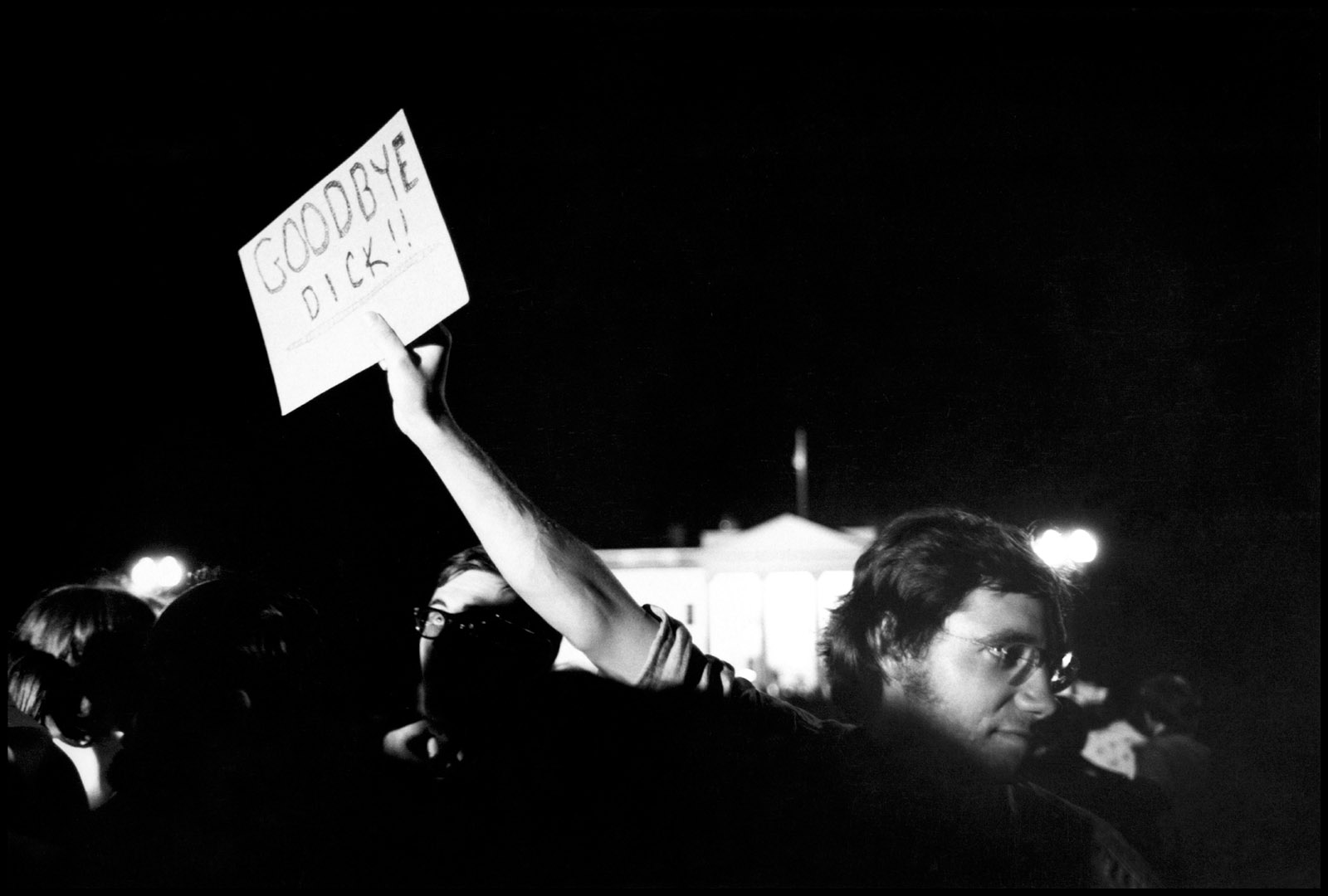

The last time publishers saw the virtue of sending books about impeachment into the market was, not surprisingly, during the Watergate crisis that ended with Richard Nixon’s resignation, on the verge of impeachment by the House, in August 1974. The best of these was also the shortest: Impeachment: A Handbook (1974), a sixty-page essay by the Yale constitutional scholar Charles L. Black Jr. In 2018 Yale University Press brought out a new edition with comments and additional material by Philip Bobbitt, a law professor at Columbia and the University of Texas at Austin. (Black died in 2001.)

The original edition arrived as the crisis of Nixon’s presidency was coming to a head. It was addressed not to scholars but to “the citizen.” Its virtue, Bobbitt explains in his introduction to the new edition, was that it didn’t instruct readers “what to think” about the specific impeachment-related questions that were swirling around Washington, but rather “how to think”: how to derive a legal answer “from the text, history, structure, doctrine, practicality, and ethos of the Constitution.”

Black made clear that, much as he had disliked Richard Nixon “from my youth,” the idea of impeachment—of Nixon or any other president—left him deeply uneasy, with “a very strong sense of the dreadfulness of the step of removal, of the deep wounding such a step must inflict on the country.” Impeachment should be approached “as one would approach high-risk major surgery, to be resorted to only when the rightness of diagnosis and treatment is sure.”

Black offered a concise explanation of the constitutional process for impeachment and conviction, borrowed by the Constitution’s framers from the English model, in which the House of Commons had the power to impeach the king’s ministers, with the House of Lords conducting the trial. The structure of the process is clear, but the Constitution is silent on the standard of proof the Senate should apply in deciding whether an impeached president is guilty as charged and should be removed from office. A mere preponderance of the evidence, the standard in most civil cases? Beyond a reasonable doubt, the standard in criminal trials? The answer was “far from obvious,” Black wrote, and his effort to reach one captures his sober approach:

Removal by conviction on impeachment is a stunning penalty, the ruin of a life. Even more important, it unseats the person the people have deliberately chosen for the office. The adoption of a lenient standard of proof could mean that this punishment, and this frustration of popular will, could occur even though substantial doubt of guilt remained. On the other hand, the high “criminal” standard of proof could mean, in practice, that a man could remain president whom every member of the Senate believed to be guilty of corruption, just because his guilt was not shown “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Neither result is good; law is often like that.

He suggests a middle ground: “overwhelming preponderance of the evidence.” Or perhaps, he adds, “a unique rule, not yet named by law, may find itself, in the terrible seriousness of a great case.”

Black makes clear that the constitutional phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” does not limit impeachment to violations of criminal law. Yet the separation of impeachable offenses from criminal offenses raises a question: “It is a cardinal principle of Western justice that criminal punishment ought not to be visited on anyone without clear warning of the criminality of his acts.” How should senators, lacking a specific provision in the criminal code to point to, apply that principle when it comes to impeachment? Black’s answer is again typical of the commonsense judgment that pervades his book:

All we can say is that a conscientious senator ought to insist upon being quite clearly convinced that the impeached official knew or should have known the charged act was wrong before he votes for conviction. This simple rule should resolve many difficulties.

“What did the president know and when did he know it?” This question, posed to witnesses by Senator Howard Baker of Tennessee, the ranking Republican on the Democratic-controlled Senate Select Committee investigating Watergate, stands alongside John Dean’s “we have a cancer within, close to the presidency, that’s growing” as the most famous phrase in Watergate lore. Elizabeth Holtzman, who as a freshman member of Congress sat on the House Judiciary Committee that voted to impeach Nixon, reminds us in The Case for Impeaching Trump that Baker’s question was not meant to indict the president but to exonerate him. Baker was a “strong Nixon partisan” who assumed that “the answers from witnesses would show that Nixon knew nothing and wasn’t involved.” Yet—and this is Holtzman’s point—“when the answers showed otherwise, Baker bowed to reality and supported a thorough inquiry that would lead to the truth.”

Holtzman offers the Watergate investigation as a model for the kind of open, wide-ranging inquiry that she argues is necessary now:

A fair, lawful, bipartisan impeachment inquiry into President Trump involves analyzing, with a clear head and heart, what he has done and what the Constitution requires. It means agreeing that we do not know where it will take us and that we do not know what the votes will be, agreeing to seek and accept the truth no matter what it turns out to be, whether it exonerates or inculpates the president.

Holtzman’s brief against Trump is not limited to Mueller’s mandate in the Russia investigation. (Her book was written months before its conclusion.)She argues that “the standard for commencing an impeachment inquiry has been more than met” by “a far-reaching and continuing groundswell of assaults on the rule of law.” She includes evidence from the foreign and domestic Emoluments Clause lawsuits against the president and, most strikingly, invokes Trump’s immigration policy, undertaken “without lawful authority,” that led to the separation of thousands of children from their parents:

A president who so deliberately, cruelly, and casually inflicted serious mental and psychological harm on thousands, manifestly on an ethnic basis, as a deterrent to others and as a political tool to get legislation passed without regard to the rights of children and parents, has subverted the Constitution. He poses a direct and immediate threat to the rule of law.

Holtzman’s book is a reminder that in considering what to do about President Trump, Congress need not—in fact should not—limit itself to the evidence compiled by Mueller. An appendix usefully contains the three articles of impeachment that the Judiciary Committee adopted and sent to the full House on July 27, 1974. With fourteen numbered specifications plus the charge that the president failed “without lawful cause or excuse to produce papers and things” subpoenaed by the committee, it concludes:

In all of this, Richard M. Nixon has acted in a manner contrary to his trust as President and subversive of constitutional government, to the great prejudice of the cause of law and justice, and to the manifest injury of the people of the United States.

Wherefore, Richard M. Nixon, by such conduct, warrants impeachment and trial, and removal from office.

Thirteen days later, Nixon resigned.

Laurence Tribe and Joshua Matz, clearly no admirers of President Trump, nonetheless approach impeachment skeptically in To End a Presidency: The Power of Impeachment. There are three “vital questions” to ask, they write, before starting down the road to impeachment:

First, has the president engaged in conduct that authorizes his removal under the standard set forth in the Constitution? Second, as a matter of political reality, is the effort to remove the president likely to succeed in the House and then in the Senate? And third, is it genuinely necessary to resort to the impeachment power, recognizing that the resulting collateral damage will likely be significant?

Tribe, a well-known constitutional scholar at Harvard, and Matz, his coauthor on a previous book (Uncertain Justice: The Roberts Court and the Constitution, 2014), are not as sanguine as Holtzman about the applicability of lessons from the Nixon impeachment. Removal of a president, they write, could lead to either “a period of disruptive political reconstruction” or “productive dialogue about reform and reformation…. The Nixon case exemplifies both possibilities at once”: it left a generation “permanently scarred” by cynicism about government while at the same time ushering in a determination “to shield integrity in politics.” And we can’t be sure that an impeached and convicted president will leave the scene gracefully. “In some circumstances,” they warn, “a desire to protect democracy may ultimately cut against promoting or pursuing impeachment” because “even a well-justified impeachment poses grave risks.” The main threat is that impeachment “turbocharges forces of dysfunction and despair in our democracy” and leaves an embittered minority that regards the process as an illegitimate coup.

So what to do about Trump? Be very careful, Tribe and Matz advise, warning against the “fantastical thinking about impeachment’s potential” that has “become increasingly common in anti-Trump political circles…. We must abandon fantasies that the impeachment power will swoop in and save us from destruction. It can’t and it won’t. When our democracy is threatened from within, we must save it ourselves.”

That might be a fitting last word, except that Tribe has changed his mind. “I’ve warned that impeachment talk is dangerous, but the time has come,” he wrote in an Op-Ed published in USA Today on April 21, after reading the Mueller Report. He no longer sees the unlikelihood of conviction and removal as a deterrent. Hearings should begin immediately, he wrote, with the Mueller Report providing the roadmap:

The report is unequivocal in concluding that even if Trump is criminally innocent of obstruction, it is not for lack of trying. The main reason the investigation wasn’t completely thwarted was not that the president didn’t “endeavor” to thwart it—the definition of criminal obstruction—but rather that Trump’s subordinates refused to comply.

3.

Should the House Democrats take a cue from Tribe and proceed to impeachment despite the seeming impossibility that the Senate would vote—by the constitutionally required two-thirds majority—to convict Trump and remove him from office? That question confronted the Democrats from the start and stymies them still.

In an interview with The Washington Post two weeks before Mueller issued his report, Speaker Pelosi rejected impeachment as too divisive in the absence of bipartisan support; Trump is “just not worth it,” she explained. She maintained that position following the report’s release, planning instead to hold dramatic televised hearings featuring the inquiry’s main witnesses, with the goal of getting the report’s crucial findings before a public that most likely had not read a word of it.

The administration’s stonewalling has thwarted that strategy. The White House is resisting all subpoenas seeking testimony from current and former officials. The president claimed executive privilege to keep Congress from obtaining the full, unredacted report. The House Judiciary Committee voted along party lines to hold Attorney General Barr in contempt for refusing to testify before the committee, a move that allowed the committee’s Democrats to let off some steam but did nothing to advance the project of bringing the facts to the people.

Barr himself dismissed the contempt vote as part of a “political circus,” and The Wall Street Journal accused the House Democrats of trying to conduct a show trial, a “pseudo-impeachment so they don’t have to undertake a real one.” A twelve-page letter that the new White House counsel, Pat Cipollone, sent Representative Jerrold Nadler, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, on May 15 oozes with disdain. “The White House will not participate in the committee’s ‘investigation,’” Cipollone wrote, placing the word in scare quotes, “that brushes aside the conclusions of the Department of Justice after a two-year-long effort in favor of political theater pre-ordained to reach a preconceived and false result.”

The battle for control of the narrative goes on. In the face of all this, the House Democratic rank and file, particularly younger members, are getting restless. “I believe that we are headed toward an impeachment inquiry,” Jamie Raskin, who represents suburban Maryland and serves on the Judiciary Committee, said on MSNBC on May 18. Speaker Pelosi herself has moved from “no” to “go slow.”

Although the risks of launching a failed impeachment are obvious, it seems to me that there are clear benefits as well. An impeachment inquiry would likely waive the grand jury secrecy requirement that the Trump administration is relying on to withhold release of the full Mueller Report. And as growing numbers of Democrats appear to be concluding, there’s a case to be made that the House has an obligation, moral if not strictly constitutional, to hold up to the light strong evidence of serious wrongdoing by the chief executive, so that whatever the ultimate result, the public will be able to judge for itself on the basis of facts rather than spin.

Maybe, after more than two years of President Trump, what we need more than anything is a collective reminder of what we have a right to expect from the occupant of the White House—how a president should behave and what the presidency should be. In that vein, I end this essay by recommending a book that has received too little attention since its publication last year. It’s not an impeachment book. In fact, it’s a how-to-avoid-impeachment book by a political scientist at Brown University, Corey Brettschneider.

He has written The Oath and the Office: A Guide to the Constitution for Future Presidents as an extended memo to anyone who might be considering a run for the White House. It has chapters about the powers the Constitution bestows on the president as well as on the constraints it imposes. Where have presidents gone wrong, and where have they lived up to the Constitution’s ideals? Brettschneider hands his hypothetical candidate a challenge that should speak to all of us. “As president,” he writes,

you will be constrained by these legal dynamics of the Constitution. But far more integral to your presidency is something else: the Constitution’s political morality. By this, I mean the values of freedom and equality that inform the document beyond its judicially enforceable requirements. We can tell whether presidents embrace the Constitution’s values not just by their executive orders or official appointments, but by how they speak to the American people. No court can tell you what to say. But you still must be guided by the Constitution in this crucial endeavor. As president, you should speak for all of us—and more, you should speak for what our country stands for, and aspires to be.

—May 30, 2019

-

1

Harvard University Press, 2017; reviewed in these pages by Noah Feldman and Jacob Weisberg, September 28, 2017. ↩

-

2

The report is available from several other book publishers as well, including Melville House and Skyhorse (whose edition includes an introduction by Alan Dershowitz). ↩

-

3

The New York Review, May 23, 2019. ↩