There has now been more than half a century of worsening economic inequality in America. Until the late 1960s, incomes had been growing more equal for nearly four decades: through the Great Depression and World War II and then the Korean War, through the placid Eisenhower years, even through most of the Vietnam War and the social turmoil of that time. Many thoughtful observers expected the trend to continue indefinitely. Ever greater equality was supposedly the hallmark of a maturing economy and an advancing democracy. But 1968 was the turning point. As the years passed, what at first seemed a statistical blip became a matter of curiosity among economists, and in time a focus of increasingly widespread public concern. In 2017, the standard measure of inequality of family incomes was 29 percent higher than it had been fifty years ago. Millions of Americans who take no interest in discussing economic issues as such, much less in examining economic data, complained about the increasingly visible concrete manifestations of ever greater inequality.

Along the way, however, the structure of economic inequality has changed. From 1968 until sometime in the 1990s, less equal incomes mostly reflected diverging wages, as the most educated and skilled workers earned ever more than those in the middle, while those in the middle earned ever more than those with the least education and the least valuable skills. The issue that had obsessed theorists during the nineteenth century—the division of the fruits of economic production between people who do the work and those who own the capital that the workers use—was of little interest, since the division never seemed to change much. In the mid-1950s, 63 percent of all income generated by American business was paid out to labor and 37 percent to capital. In the mid-1990s the split was 62 percent versus 38 percent.

The last few decades have been different. On average over the past five years, wages, benefits, and other returns from working have garnered only 57 percent of what American business has produced. The other 43 percent has accrued to business owners, mostly including corporations and their shareholders. The change from two decades ago may seem small, but 5 percent of the nation’s total business income is well over $500 billion. If it had gone to workers rather than owners, inequality would have been significantly reduced. Moreover, like the earlier pattern of widening wage differentials that favor education and skills, this shift away from labor and toward capital is not unique to America. Over the last few decades the labor/capital split in Germany has moved from 67/33 to 60/40, and in Japan from 55/45 to 52/48. Even in China—still supposedly a communist country—it has gone from 43/57 to 38/62.1

This change profoundly alters the practical discussion of what should be done about economic inequality. It remains true—indeed, importantly true—that acquiring an education and gaining skills represent the best route to a middle-class income for millions of workers. College-educated men today earn 30 percent more than those who only graduated from high school, and they in turn earn 15 percent more than high school drop-outs. The differentials are smaller for women, but still significant: 15 percent and 12 percent, respectively.2 No young person should ignore those enormous incentives. Analogous, though weaker, incentives make acquiring any of a wide variety of skills, such as programing computers, or operating complex machinery, economically attractive for older workers as well. (And for children at risk of not doing well in the earliest grades, the economic returns to receiving effective preschool education are even greater.)

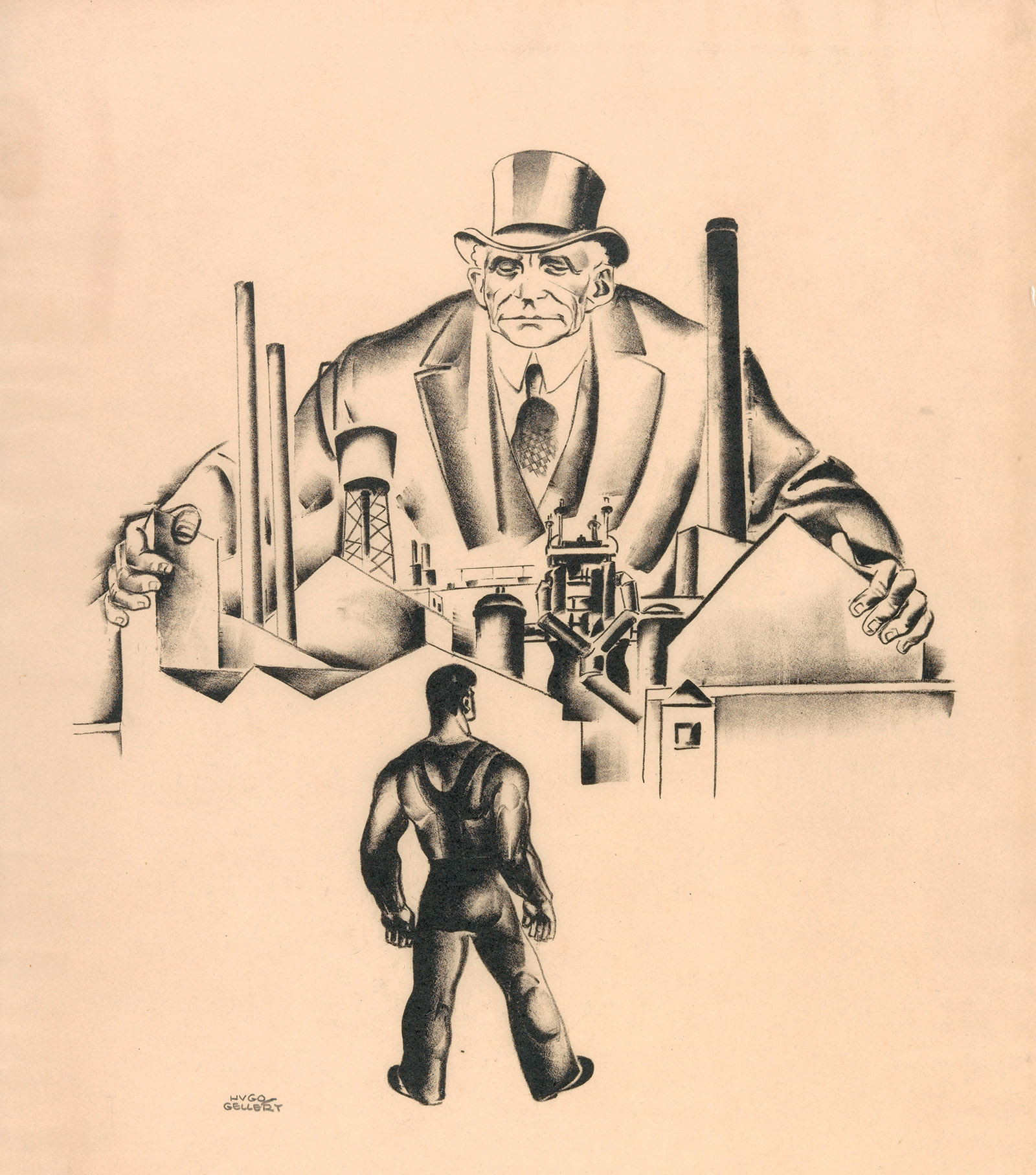

Even so, wage differentials are just that: differences in what one working person earns versus another. If widening inequality today also reflects the movement of income away from employees toward whoever owns the factories and offices where they work, and the computers and other machinery they use, merely changing the supply of workers with one education level versus another will not arrest the trend. Ownership of wealth is far more skewed than incomes are, and ownership of productive capital (or claims to productive capital, like shares in a business corporation) is more skewed still. The more the economy’s total product goes to the owners of capital, the more unequal the distribution of incomes will be.

Because this phenomenon is relatively new, it has attracted much less attention than the older matter of widening wage differentials. Despite a flurry of recent research, no one yet knows just why the division between labor and capital is shifting. That it has been doing so across much of the industrialized world, even including China, goes against explanations that rely heavily on institutional arrangements specific to the United States, such as the declining power of labor unions or the erosion of the minimum wage due to price inflation. Something more worldwide, and more fundamental, must be going on.

Advertisement

One plausible cause is the ongoing fallout from the introduction of hundreds of millions of new workers, from China, India, and elsewhere, into the international labor force. But even that explanation would require a significant change in the way economists have long thought about the production process. Under the most commonly used model, having more available workers wouldn’t affect the division of total income between labor and capital; more workers would be getting paid, but each would receive less than workers had previously earned, so that their wages in total would remain the same compared to total production. Another possibility is that widening inequality is the result of some change in the technology of production itself, perhaps associated with the increasing reliance on robots and artificial intelligence.

Whatever the cause, the reduced reward to labor is important, and not merely for workers’ incomes. Not all of what matters about economic inequality can be measured in dollars. People also care about security, working conditions, job schedules, status, and perceptions of respect. Even without yet knowing why labor’s share of income is shrinking, therefore, some observers have begun to ask what to do about it. Thomas Piketty’s 2014 best seller Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which first brought widespread public attention to the role of changing income shares in accounting for the general widening of inequality, proposed a wealth tax. Several authors (mostly not economists) have advocated broad-based income redistribution schemes, like a universal basic income.3

David Webber, a law professor at Boston University, suggests a different approach. In The Rise of the Working-Class Shareholder, he points out that a not insignificant amount of the wealth currently invested in corporate capital in the United States comes from the deferred wages of low- and middle-income workers—not in the form of individual savings and 401(k) plans, but in institutional pension funds sponsored by employers like city and state governments and school systems, as well as by the unions to which many workers still belong. These funds are there to finance workers’ retirements. The question Webber poses is whether this must be their only function. His answer is no.

As large-scale institutional investors, pension and union funds are especially well suited to engage in various forms of shareholder activism. A long-standing concern about corporate America has been the lack of effective external governance. Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means first called attention in the 1930s to the separation between the ownership and control of US corporations, as larger numbers of individuals were increasingly owning tiny shares in many different companies.4 Not only has that trend continued, but over time institutional investors have become vastly more important. US-based pension funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, and other investment institutions now hold 44 percent of all outstanding stock issued in the United States.

Most of these institutions, however, have reasons for not expressing much of an opinion on how the companies whose shares they own are run (apart from standard matters like wanting the firms to obey the law and their directors to show up at meetings). Firms that manage mutual funds often seek business managing the 401(k) plans of companies in whose shares their funds invest, and insurance companies likewise sell various products and services to companies whose shares they own. No one wants to offend their current or potential customers. As Webber explains, these reasons for remaining passive do not apply to state and local government–sponsored pension funds, or to those of unions.

Webber argues that these pension funds should actively exert their influence on the conduct of companies of which, as is often the case, they are among the largest shareholders. They represent, he says, “a tremendous source of power for labor”: “Pensions should assess the effects of their investments on their workers, including their jobs.” Webber’s point lies in that last phrase. Everyone understands that pension funds are there to finance workers’ retirement. The issue is whether they should, and legally can, take other considerations into account.

Webber is not shy about the political implications of what he proposes, along with the basic economic matters at stake. In light of what has been happening to so many Americans’ jobs, wages, and working conditions, he argues, shifting the balance of power between labor and capital is precisely what the country needs. Under the “worker-centric legal and policy vision” that he urges,

labor would have massive leverage using its pensions to its advantage in hiring and future pension contributions. That leverage would administer an adrenaline shot to the working class that could keep it off life support and send it back into the political arena in the twenty-first century.

Webber makes a persuasive case for the potential power of the pension funds he seeks to enlist in this effort. “What other voice in our society elicits the same level of responsiveness from inside corporations, hedge funds, and private equity funds?” he asks.

Advertisement

These pension funds, with the assets and power they have accumulated…operate inside the private sector, inside the market, as shareholders. They benefit from rules designed to keep power and resources marshaled there. Shareholder empowerment empowers them.

And although other kinds of institutional investors, such as hedge funds, could in principle play the same game—most likely weighing in on the opposite side of many labor issues, and therefore offsetting the pension funds’ clout—they are largely on the sidelines.

Perversely, these particular shareholders [pension funds, that is] are more powerful than most because they operate in the private sector unencumbered by business conflicts of interest that keep other shareholders quiet when their rights are violated or their interests subverted.

Webber backs up his argument for the pension funds’ potential shareholder power with examples of corporate battles they have fought and won. The victories so far have mostly been in fights over corporate governance. Pension funds have taken the lead in forcing companies to accept such standards as giving shareholders the ability to put questions to a vote on companies’ annual proxy statements, having majority votes enforced, imposing “clawbacks” to prevent rewarding management for surges in profits that quickly disappear, separating the roles of board chair and management CEO, and giving shareholders a vote (albeit not a binding one) on the pay of the executives who supposedly work for them—all of which are now increasingly accepted as best business practice.

More rarely, and not always with success, pension funds have opposed companies’ efforts to eliminate jobs or downgrade wages and working conditions. Webber gives examples of those battles too, both the successes and the failures. In 2003, following a mostly unsuccessful strike against the Safeway supermarket chain over cuts to wages and health benefits, a group of pension funds including the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and the New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) led a shareholder revolt against Safeway’s CEO and board. The CEO survived, but three of his allies left the board, two who remained were removed from important committees (including the one that sets the CEO’s compensation), and one of the more independent outside board members became the company’s official lead director.

In 2013 the American Federation of Teachers published a list identifying hedge funds whose managers were active in the movement to defund public schools in favor of charter schools, including cutting teachers’ pensions. As a result, some union and public employee pension funds rethought their investments, and some of the hedge fund managers rethought their personal activism. Webber’s goal is to make such efforts more frequent, and more successful.

Webber is no doubt right that pension funds can act to support workers’ interests in this way. But should they? Is it even legal?

The ultimate purpose of these pension funds is to benefit the workers whose implicitly deferred wages provide the money that the funds invest. Webber makes a good case that there is no logical reason always to define those workers’ interests narrowly, as just their future retirement benefits. If firing lots of workers and cutting the wages of those who remain makes a company more profitable, its stockholders will earn a higher rate of return; and if a pension fund is among the stockholders, that higher rate of return will make possible larger retirement benefits per worker. But a worker whose job disappears, or who now receives lower wages, may well come out worse off even with the larger retirement benefits. Why not take the whole picture into account in deciding how to vote the pension fund’s shares in the company? Why should the rate of return on the investment be the only consideration?

What makes this reasoning problematic is the matter of who “the workers” are. In most cases, few if any of the workers covered by any particular pension fund are employees of the company whose conduct toward its workers is in question in this kind of dispute. (If the fund is sponsored by a state or local government, then none of the workers it covers are so employed.) What Webber wants, therefore, is for one group of workers to sacrifice their rate of return, and therefore their future pension benefits, in support of jobs and wages and working conditions for other workers. Some notion of solidarity, in which all workers’ interests are lumped together, must underlie such a sacrifice. From Webber’s rhetoric, it is clear that worker solidarity of this kind is what he has in mind much of the time. But he does not explicitly say so, or even acknowledge the potential conflicts.

Even if everyone in the economy worked for the same employer, however, if their pension fund were to follow Webber’s path some workers would still gain while others lost. Saving jobs and maintaining wages would benefit workers who are still working—the younger they are, the more so. But workers already retired (or close to retirement) would only (or mostly) incur the loss of pension benefits consequent on the fund’s lower rate of return. A similar line of argument would apply if some pension fund bore the expense of fighting for corporate governance practices like proxy access and clawbacks, except that those changes would likely improve the rate of return of a company’s stock. The issue in that case is not that some would benefit at the expense of others, but rather that some would bear the cost of benefiting everyone. Trying to take into account yet other potential effects, like the loss of tax revenues from lower wages, or from declining local populations if workers who are fired move away, makes judging the merit of Webber’s proposal even harder.

For pension funds covering the employees of state and local governments or school systems, yet a further complication is whether the rate of return earned by the fund actually affects the benefits paid to retirees. As Webber emphasizes, most pensions provided to public-sector employees in the United States are defined benefit pensions. Unlike in a typical 401(k) plan in the private sector, under which workers and their employer contribute to individual worker-specific accounts, and the worker’s benefit in retirement depends on how much goes into the account and what rate of return it earns over time, under a defined plan the worker is promised a set monthly payment, usually depending on years of service and final salary. Holding aside the possibility of default, which Webber repeatedly downplays, a higher rate of return earned on the invested assets of such a plan therefore does not result in retirees’ receiving larger benefit payments. Instead, the taxpayers have to put up less money.

State and local government pension funds—which is to say, most of the funds toward which Webber directs his argument for shareholder activism—would therefore face an economic trade-off quite different from the one he presents. The gains, from saving jobs and maintaining wages, would go in the first instance to the workers at whatever company is the target of the shareholder action. Any loss of return on the company’s stock held by the pension fund would be a loss to the taxpayers, not to current or future retirees. (Here again, further complications are that workers pay taxes on their wages and that fired workers may move away.) The activism that Webber advocates would advance the interests of some groups of workers at the expense of the taxpayers, not other groups of workers.

Wholly apart from any questions about Webber’s argument, the path that he urges faces serious challenges—“profound threats to labor’s capital” as he sees them. One, which he anticipated in writing his book, has already become a reality. Last June the US Supreme Court—by the usual 5–4 vote, with the usual suspects on each side—weakened public-sector employees’ unions by barring them from collecting fees from nonmember workers on whose behalf they collectively bargain with state and local government employers. The change does not immediately impede these funds from engaging in shareholder activism of the kind Webber favors. But if weaker unions lead to smaller contributions to the pension funds, then over time the funds’ potential clout as shareholders will diminish.

A second potential challenge is from 401(k) plans. Most American corporations used to offer their employees defined benefit pensions, just like the ones that state and local governments have. Few companies still do. Over the last forty years the private sector has increasingly moved to 401(k) and other analogous defined contribution arrangements to provide for their workers’ retirement. As Webber points out, these systems place the risk—the risk that not enough is contributed, as well as the risk that the invested assets bear low returns—squarely on the individual worker. If any retiree ends up with too little income to live on, or even if all of a company’s workers face that plight, the company is not responsible. Although it is not the point of his book, Webber shares the widespread concern that the great majority of Americans who look to such plans for their retirement income will find them insufficient.

But the ongoing shift to 401(k)-type plans has a further effect that does bear directly on Webber’s proposal. Multi-billion-dollar funds, representing the retirement assets of thousands or even millions of workers, are large enough to make shareholder activism feasible. Large pension funds, like CalPERS and NYCERS, own significant positions in the stocks of numerous companies. Managements have to take them seriously. Such funds also have sizable staffs, capable of engaging with corporate managements as well as forming alliances with other shareholders. Even if the same amount of money is invested, having it in individual 401(k)-type accounts rather than in aggregated funds would reduce the opportunity for meaningful shareholder activism.

And then there is the legal question. Suppose whoever has fiduciary responsibility for directing a pension fund’s investments—in many cases the fund’s board of trustees, but for some state or local government employee funds a designated public official—decides to follow Webber’s advice. Are they allowed to do so? Can they legally take into account the gains that its shareholder activism would deliver for workers—either the workers covered by the fund itself or, perhaps in a spirit of solidarity, other workers? Or must they only consider factors affecting the rate of return earned on the fund’s invested assets?

Webber is a lawyer, and his opinion is unambiguous: “I do not think that federal or state law requires, or should require, funds to ignore the overall impact of a fund’s investments on workers in the name of maximizing returns.” Similarly, he writes, “In the American context, it is often taken as a given that a business case and only a business case for investment action is appropriate…. I argue that the law suggests otherwise.” Webber’s opinion is not merely his own. He cites two court decisions, one from 1986 in the 11th Circuit Federal Court of Appeals and one from 2006 in the California Court of Appeals, that have “implicitly blessed” the principle underlying his view.

Webber acknowledges, however, that the matter is uncertain. Some courts—most importantly, the Federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit—have been positively hostile to shareholder activism of just this kind. Moreover, as the press of events increasingly reminds us, in the United States the law is ultimately what nine people say it is. What Webber’s book presents is not a legal argument but rather an economic and political one, and recent experience suggests that economic and especially political arguments count for a lot in determining what the Justices decide on any given issue before them. Whether the argument Webber presents would survive the scrutiny of today’s Court remains to be seen.

-

1

I am grateful to Brent Neiman for sharing his updated data; see Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman, “The Global Decline of the Labor Share,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 129, No. 1 (February 2014). ↩

-

2

I am grateful to David Autor for sharing his data; see David H. Autor, “Skills, Education, and the Rise of Earnings Inequality Among the ‘Other 99 Percent,’” Science, Vol. 344, No. 6186 (May 23, 2014). ↩

-

3

I reviewed one such proposal, by Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght, in these pages, October 12, 2017. ↩

-

4

Adolf A. Berle Jr. and Gardiner C. Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (Macmillan, 1932). ↩