At the 2001 Rotterdam film festival, I was ushered into the presence of the acerbic German filmmaker Werner Schroeter, whom I hoped to persuade to assist in my—futile, as it turned out—quest to secure the prints necessary to mount a retrospective of his work in Toronto. Clad in black and one of his signature broad-brimmed hats, Schroeter grew increasingly irritated, affecting extravagant indifference to my appeal before finally surveying me head to foot with an exaggerated glance. Amplifying his accent, he hissed: “Yesssss, vell, you do look very—professional!” He loaded what seemed like sixteen syllables into an adjective that represented much that was repugnant to his anarchic nature.

“I know I’m rather arrogant,” Schroeter admits in his memoir, Days of Twilight, Nights of Frenzy, but the witty, imperious person I encountered that evening in Rotterdam appears only intermittently in this chronological plod through the director’s life and career. Though he was the maker of such ecstatically florid farragoes as The Death of Maria Malibran (1972), Eika Katappa (1969), and The Rose King (1986), and an opera-obsessed artist whose formative influence was Les Chants de Maldoror, the Comte de Lautréamont’s surrealist sextet of grotesque prose cantos, with their “somber, poison-soaked pages,” he proves a surprisingly uninspired essayist and an obtuse raconteur. There is more twilight than frenzy in these crepuscular chapters.

Schroeter’s diffident tone and dubious phrasing emerge early as he recounts his father’s determination to move the family away from the German Democratic Republic after suffering under “another repressive regime,” which is a strange way to describe the Nazis. Born just as World War II was ending, at age six Schroeter escaped with his family, including his beloved Polish grandmother, from the resort town of Georgenthal in Thuringia to a working-class housing development in the heavily bombed West German city of Bielefeld. “I still remember the gloomy ruins,” Schroeter notes about his new home, though one assumes he means the devastation left by the war and not the nearby tower and catacombs of the thirteenth-century Sparrenburg Castle, which may have provided him with enough moody Romantic landscape to inspire his later taste for overgrown architraves and crumbling amphitheaters. In the most extreme indulgence of that attachment to relics, he shot his version of Oscar Wilde’s Salome (1971) in the picturesque temples of the ancient city of Baalbek, Lebanon. About the construction of a different kind of edifice, also eventually to become a ruin, Schroeter writes, “Incidentally, the building of the Berlin Wall left me cold and had no effect on the rest of our family either,” an observation both perfunctory and frivolous. (Schroeter, a connoisseur of triviality, would not consider the charge insulting.)

In a photograph included in the recent monograph on the director edited by Roy Grundmann, a shirtless, teenaged Schroeter appears blond, beatific, and all but boneless, around the time he was rebelling in a household both unconventional—his father and mother each openly took a lover, he a (female) opera singer, she a Viennese actress—and conformist; his parents eventually separated but considered divorce too scandalous to contemplate. The director’s shrugging confession that his mother continued to wash and bathe him and his brother—an amateur astrophysicist from whom he was once alienated—well into adulthood suggests his impatience with psychology, his field of study before he transferred to film school. Though Schroeter repeatedly comments on his attempts to purge his art of psychology and its attendant symbolism, he does allow that his films “disclose inner experience” and proudly notes that he “once received a letter from the psychiatrist Ernest Holmes, who wanted to borrow a copy of The Death of Maria Malibran because he felt sure the film could act as a therapeutic tool in treating the psychiatric patients in his hospital.”

Schroeter seems unaware that a print of the original cut of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent classic The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), a film he revered and often paid homage to in his own work, was discovered in a janitor’s closet in an Oslo mental institution in 1981, leading to speculation that the film had once been employed in a curative program. Schroeter set one of his late films, Day of the Idiots (1981), in just such an institution, where his anxiety-stricken heroine, played by Carole Bouquet, seeks asylum from the madness of the outer world. A scatological attack on psychiatry informed by the theories of Michel Foucault and R.D. Laing, Idiots was also an implicit critique, Schroeter suggests in his book, of the institutionalization and enforced therapy of homosexuals.

As a culture-craving teenager, Schroeter experienced a quivering epiphany when he first heard Maria Callas on the radio. He christened the Greek-American diva “my spiritual mother” and accorded her the same devotion as his “natural mother,” though he once fantasized about murdering the latter with a butcher knife, still nursing resentment over her refusal years earlier to allow him to bring a boyfriend home. In his early 8mm films exploring his “tormented love” for Callas, Schroeter cleverly employs collage, bricolage, iris shots, and masking to animate still images of Callas with rapid-fire montage, fixating on the soprano’s intensity in Lucia di Lammermoor or Tosca. Schroeter gives Callas preeminence in Days of Twilight, which opens with an account of their first meeting at a dinner at the Greek embassy in Paris; in a typical segue from the sublime to the abject, the director recalls both the soprano’s splendor—she “wore a beautiful emerald-green Balenciaga dress with magnificent jewelry”—and his own copious vomiting the day before their encounter.

Advertisement

Callas’s death in 1977 is the first Schroeter records in what amounts to a chronicle of “ways of dying,” to evoke the title of a work by Ingeborg Bachmann, whose experimental novel Malina he brilliantly filmed. His memoir catalogs countless deaths from AIDS, drug overdose, alcohol abuse, and especially cancer—“my whole family has died of that disease,” he writes early on. (Schroeter died of throat cancer in 2010.) Callas supplied, after Schroeter’s fervent Catholicism, his other lifelong religion, so his reaction to the news of her death seems bizarrely muted: “It shook me badly…. It seemed to me an inconceivable phenomenon.” Given the stilted quality of the text—the author says he isn’t “cultivating a stance of sadomasochism” or “absorbed in my tragic concept of the world”—one wonders how much of the problem lies with the flat, erratic translation, which is puzzling since it was one of the last projects of the late Anthea Bell, whom W.G. Sebald chose to translate Austerlitz.

Callas would soon be joined on Schroeter’s asynchronous soundtracks with the kitschiest of pop songs and the most preposterous flights of coloratura. This naïf-postmodernist pilfering intensified in his early film Argila (1969), which intersperses Bruch, Donizetti, Vivaldi, Verdi, Liszt, Beethoven, and Stravinsky with the “satin sound” of Brook Benton’s 1962 hit “Hotel Happiness”:

I’m checking out of Hotel Loneliness

All my lonely days, they’re all through

I’m checking into Hotel Happiness (oh, yeah)

Because, darling, I found you

I left my teardrops in that old lonely room…

Lurching rather than segueing from tune to tune, Schroeter’s omnivorous soundtracks sample Saint-Saëns and the Andrews Sisters, Verdi and Elvis, Wagner and Percy Sledge, Vienna waltzes and rockabilly. Schroeter saw no appreciable difference between Bizet’s Carmen, whose cry “La mort! La mort! Encore la mort!” he transformed into his own frequent refrain of “Tod, Tod, Tod,” and Marty Robbins’s country-and-western Carmen: “Tonight there’ll be no room for tears in my bedroom/Tonight Carmen’s coming back home!”

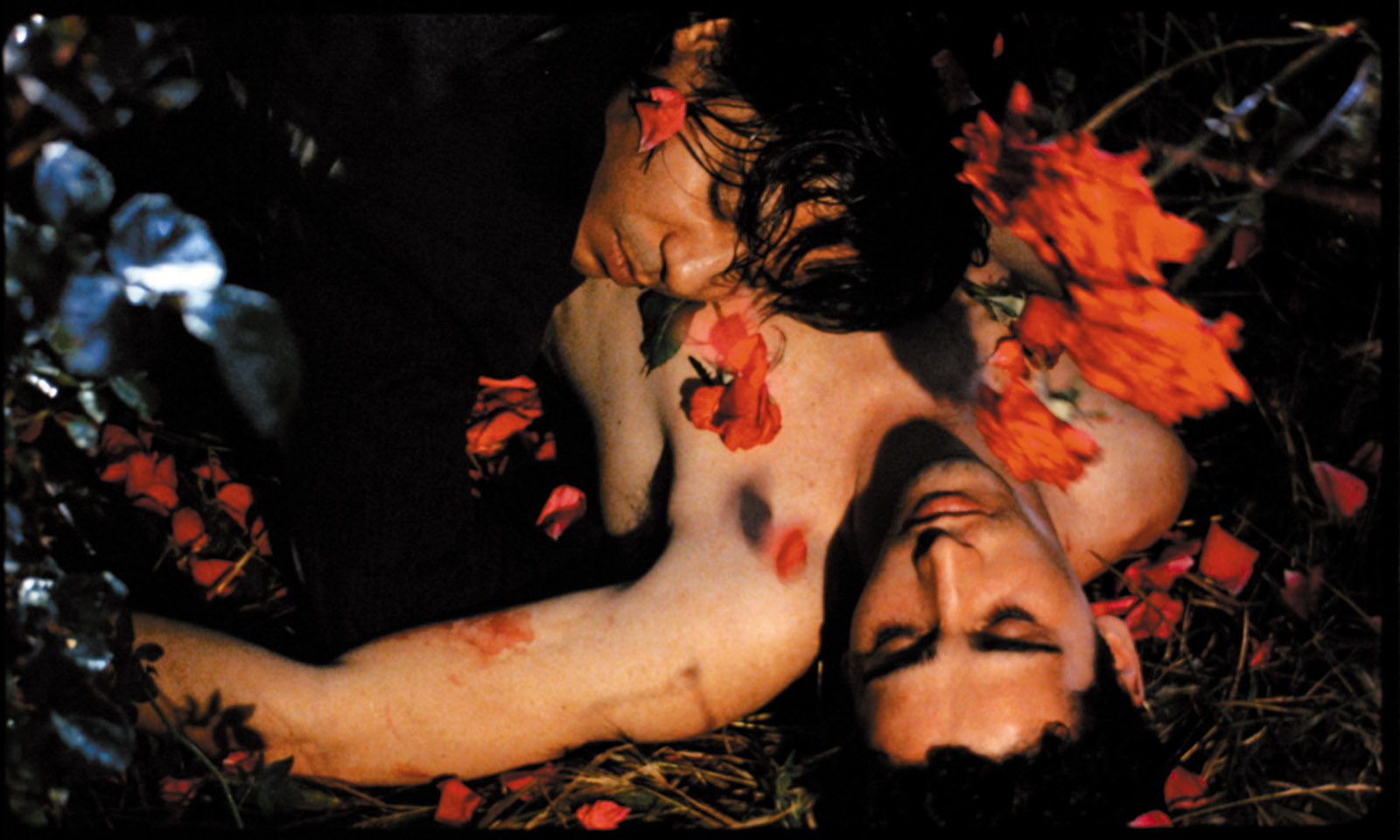

Schroeter loved Robbins’s Maricopa County version of Carmen’s homecoming, in which a nervous husband anticipates his wife’s return by putting “brand new sheets on the bed,” so he repeated the song twice, back-to-back, in The Death of Maria Malibran. In the exquisite opening sequences of Schroeter’s homage to the celebrated nineteenth-century soprano who expired at the age of twenty-eight after collapsing onstage—leading to apocryphal claims that her death was the result of too many taxing bel canto encores—a Sapphic surfeit of sequined, heavily lacquered actresses strike poses of attenuated rapture. They kiss catatonically in extreme close-up, their flesh and hair lit with the glistening halation of a Vermeer as Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody and Beethoven’s Triple Concerto take turns on the soundtrack. Schroeter, an intuitive genius at lighting effects, achieved what he called a sculptural “fake three-dimensionality” in the close-ups by employing the low color sensitivity of Ektachrome stock. When the actresses, seemingly weighed down by fake eyelashes that could double as helipads and lipstick applied as if with a backhoe, rouse themselves from their stupor, they manage to lip sync a series of pop songs and opera arias, except there is precious little sync, their busy mouths rarely matching the lyrics they appear to emit. (Notoriously, Warhol superstar Candy Darling growls “St. Louis Blues” in caramel-colored blackface.)

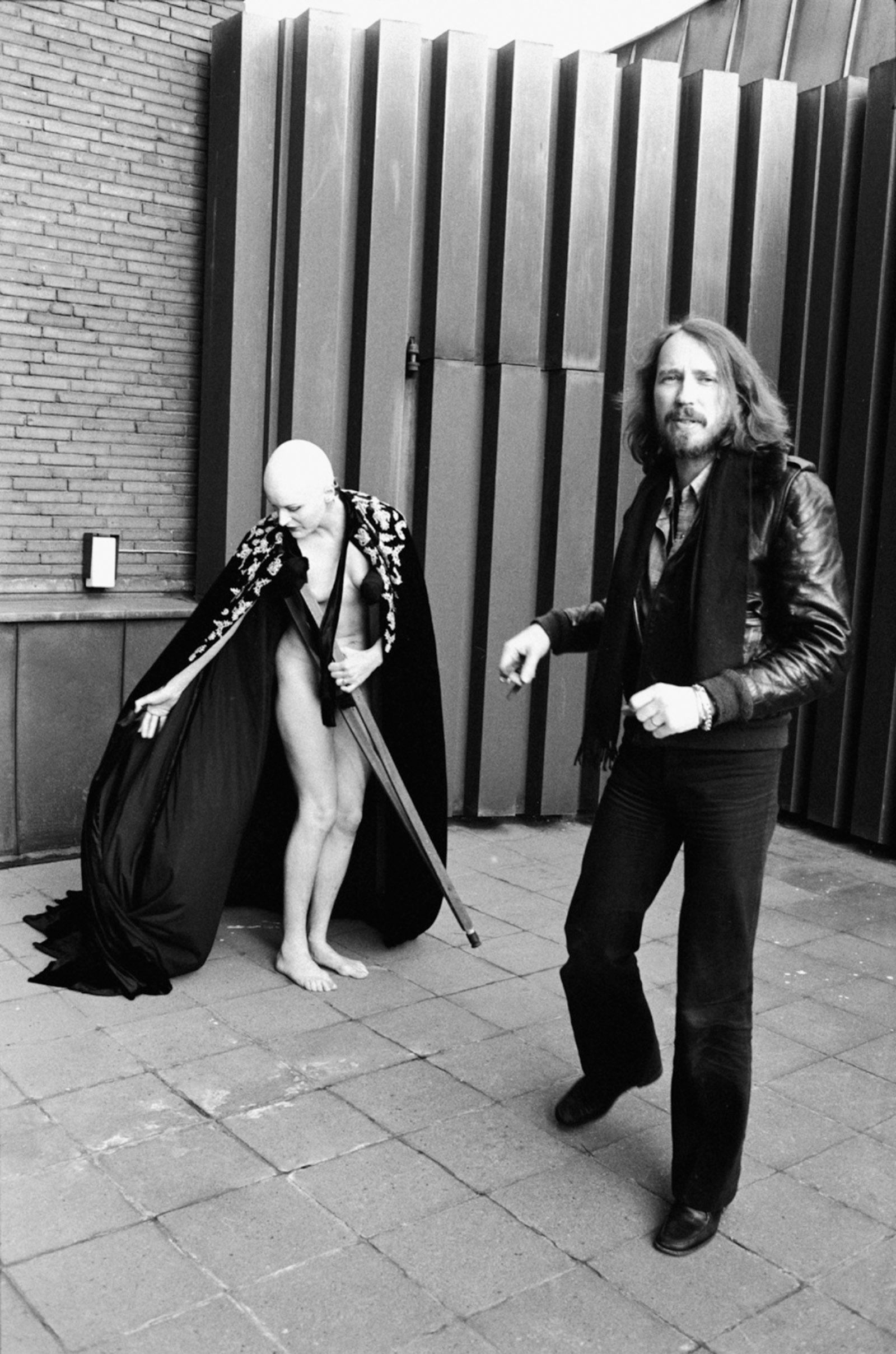

The Death of Maria Malibran gathers some of the actresses who would constitute Schroeter’s second family: Ingrid Caven, Christine Kauffman, and Magdalena Montezuma. Schroeter discovered Montezuma as Erika Kluge, an insecure twenty-two-year-old bar waitress, renamed her after the Mexican ruins of his Romantic reveries, and transformed her into a jut-jawed diva who reigned over his cinema and theater productions until her death at forty-one. The actress was capable of transforming her features into all manner of fierce oddity, from a bald, android-looking Herod in Salome to a mock-Wagnerian Kriemhild from the Nibelungen saga, brandishing two comically massive golden braids in Eika Katappa.1

Advertisement

In his obsession with doubles, doppelgängers, and dualities, Schroeter sometimes paired the dusky Montezuma with her blond, glamorous opposite, Carla Aulaulu—“there was something of Marilyn Monroe about Carla,” he observes—whose improbable last name, an ululating yodel, she invented to replace the more prosaic Egerer. Aulaulu was also a prominent member of the stock company of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Schroeter’s loyal friend and champion, who once wrote an article in his defense after the gay activist filmmaker Rosa von Praunheim (né Holger Mischwitzky) decried the pessimism of Schroeter’s comparatively big-budget and conventionally narrative foray into Italian Neorealism, The Kingdom of Naples (1978). Von Praunheim had once been both Carla Aulaulu’s husband and Schroeter’s first long-term lover.

The Kingdom of Naples, which Von Praunheim reviled for its humorlessness and obsession with death and despair, indulged Schroeter’s tendency to romanticize southern cultures. Reminiscent of Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (1960), which chronicles the miserable fate of a family from Lucania that moves to Milan, Kingdom is part Brechtian allegory—a bag of flour for which a mother prostitutes her young daughter is emblazoned “USA”—part operatic family saga, as it follows the misfortunes of a brother and sister in postwar Naples, from the death of Mussolini to that of John F. Kennedy.

All feverish pastiche, Kingdom ransacks Italian cinema (Lattuada, Fellini, Visconti, Pasolini) for its references, while Schroeter stocks its soundtrack with Neapolitan canzoni and the inevitable Callas. In paying homage to his Italian forebears, however, Schroeter unfortunately imbibes some of the rank homophobia of the country’s leftist cinema, especially in the figures of the film’s capitalist villain, a predatory lesbian entrepreneur whose ghastly makeup and hair signify her perfidy, and a gay pedophile who lures urchins to his lair with a fish tank. (Their closest cinematic relatives are the Fascist couple in Bertolucci’s 1900, released two years earlier: the eye-rolling Attila, played by Donald Sutherland, who rapes and murders a little boy, and his vicious paramour, Regina, played by Laura Betti.)

Schroeter extended his portrait of a paradisiacal south in what he called the second part of his “Italian ‘duology,’” Palermo or Wolfsburg (1980), which was the first German film to win the Golden Bear, the top prize at the Berlin Film Festival (which it shared with Richard Pearce’s Heartland). The film’s title establishes a geographic polarity that becomes a central metaphor, which Schroeter elaborates in its three-part study of a young Sicilian who travels to Wolfsburg to work in the auto industry, only to end up murdering two racist tormentors. As Pasolini did with Africa and the Middle East, Schroeter idealizes Sicily as sensual and authentic, the very opposite of his home country, which he portrays as chilly and bigoted. Each movement of the film has a different style: Schroeter applies the operatic Neorealism of The Kingdom of Naples to the Sicily sequences; replicates Fassbinder’s stylized naturalism in the Wolfsburg section; and resorts to histrionic surrealism—what he calls “a piece of exaggerated grotesquerie”—for the long final court case. When the camera floats toward an open window in the film’s final image, one feels like the character in Day of the Idiots who gasps, “I must breathe!”

Characteristically, Schroeter followed his prize-winning epic with a project that was its opposite: an intimate documentary about the Nancy theater festival, Dress Rehearsal (1980), in which he revealed that the ineffable German emotion Sehnsucht, an intensity of longing for something lost, imperfect, or irretrievable, was crucial to his sensibility. Sehnsucht certainly saturates The Rose King, perhaps Schroeter’s masterpiece, as if a sense of grievous imminent loss drove the director to a self-immolating level of intensity. Shot quickly in Sintra, Portugal, after Montezuma was diagnosed with terminal cancer, the film is a surging requiem for the actress, who died soon after its completion.

Working for the first time with cinematographer Elfi Mikesch, a still photographer who had limited experience with 35mm film, Schroeter created some of the richest images of his career, drawing on the Tenebrist sensuality of Caravaggio and Georges de La Tour, both of whom he explicitly evoked: a gaunt Montezuma, her cheekbones rendered more prominent by illness, gives a disquisition on the latter, and Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard makes a fleeting appearance. In his recollection of shooting the film in Days of Twilight, Schroeter blandly describes The Rose King as “dense and colorful,” which hardly does justice to its enamel-hard images of erotic anguish and luxuriant decay: a glistening lattice of cobwebs; a moldering Madonna; crimson roses tucked into every wound on a would-be Saint Sebastian. (When the film was released in New York, the New York Times critic Vincent Canby began his mocking review, “Werner Schroeter’s ‘Rose King’…is one of those supposedly avant-garde films that aren’t easy to write about without cracking up, but I’ll try.”)

After Montezuma’s death, Schroeter took a long hiatus from filmmaking, during which he cultivated his reputation as an innovative opera and theater director. (He would later mine his experience in these fields with a series of documentaries about aged divas revisiting their former art.) More than once in Days of Twilight, Schroeter catalogs these productions in bouts of monotonous list-making:

For instance, in 1986, in between Georg Büchner’s Leonce und Lena in Bremen and Lorca’s Doña Rosita in Düsseldorf, I also directed the splendid Mexican première of Richard Strauss’s opera Salome in Mexico City. I directed August Strindberg’s Intoxication, Samuel Beckett’s Breath, and Schiller’s Don Carlos in Bremen…. And I directed operas in Italian houses and elsewhere: in 1987 Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor in Livorno, with Jenny Drivala…as well as Luigi Cherubini’s Medea in Freiburg, and then back in Mexico City to direct a fine production, together with Kristine Ciesinski. The following year I directed Tommaso Traetta’s Antigone in Spoleto and Gaetano Donizetti’s Parisina d’Este in Basel. In 1991 there was Giuseppe Verdi’s Luisa Miller in Amsterdam, not forgetting Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk at Frankfurt Opera, Jules Massenet’s Werther in Bonn, and above all Puccini’s Tosca at the Opéra nationale de Paris—a production that remained in the repertory until the summer of 2009.

Schroeter reemerged into filmmaking with a new star, Isabelle Huppert, with whom he made two movies preoccupied with doubles—and with vomiting: Huppert pukes into her purse in Malina (1991) and gobbles the vomit of her twin sister in Deux (2002). In Malina, with a script by Elfriede Jelinek, Huppert plays an unnamed, pill-addicted authority on Wittgenstein who disintegrates in a Viennese apartment, vainly attempting to bandage walls fissured with ominous cracks. Days of Twilight reveals that the maelstrom of fire that engulfs Huppert’s flat as she and her alter ego, Malina, played by Mathieu Carrière, carry on their everyday lives oblivious to the inferno—“Sleep well!” he cries, as flames leap about her bedroom—was created without any fakery: “No tricks, no dissolves, no double exposures, nothing computer generated. The flames shown on film were real,” Schroeter insists.

Though it is invaluable for Schroeter scholars, biographers, and “cinema enthusiasts,” as the translation oddly puts it, Days of Twilight nevertheless remains somewhat wearisome due to Schroeter’s failed attempts at humor (“They also made it clear that Montezuma didn’t exactly resemble a dear old auntie working in a savings bank”), his mild reactions to controversy (which he describes more than once as “fuss”), and, mostly, his colorless language. He repeatedly likes things “very much” and finds Antonioni’s films “very much up my alley.” If his cinema offers a sluice of extraordinary images, his writing tenders a welter of clichés like “made on a shoestring”; “to cut a long story short”; “what made him tick”; “time…wasn’t ripe”; “without batting an eyelash”; “since time immemorial”; “one thing led to another”; and “dying like flies,” which is one way of characterizing the AIDS epidemic.

A great difficulty with writing about Schroeter is that it either fails to communicate the films’ outlandish splendor or, conversely, becomes imitatively overwrought in attempting to do so. In her essay on Malina in the Austrian Film Museum’s recent monograph on Schroeter, which largely collects the proceedings of a 2012 conference on the director in Boston,2 Fatima Naqvi falls into the second trap:

Flowing transformations suddenly give way to the stasis of death, but mortification becomes the precondition for rebirth. The metamorphoses intrinsic to gender performance are arrested abruptly, only to suddenly begin anew. Horrific nightmares segue into opalescent daydreams, and daytime phantasmagorias become iridescent nighttime sequences. The dissemination of the woman’s image comes to a halt only in the emptiness of the final frame—or not.

Fortunately, most of the other essays avoid similar turbidity, though some let Schroeter disappear for long stretches while they pursue a theory. The best is Christine Brinckmann’s highly informative and evocative reading of the marvelous Willow Springs (1973), a western and revenge drama in which three women, including a domineering Montezuma, sequester themselves in a stone hacienda in the Mojave Desert, affecting ritualistic poses and repeatedly listening to the Andrews Sisters’ “Rum and Coca Cola” on an old gramophone. (The song’s lyrics connect American pop culture with sexual exploitation, so are perhaps apt.) Montezuma assures a prying policeman that “life in the desert is very demanding, you know,” but the women mostly languish amid the tumbleweeds and complain about one another when they’re not luring unlucky men to their deaths in reprisal for the rape one of them endured.

The peculiar title of Brinckmann’s essay, “Leaping and Lingering,” refers to her thesis, wisely reserved for the last page of her analysis, that Francis B. Gummere’s description of the narrative structure of the Scottish traditional ballad, a form that lingers and lingers before it suddenly springs to a new part, applies to Schroeter’s construction of this nonlinear tale. Not only is the argument ingenious, but Brinckmann also does a fine job of describing both the desolate setting of the film and the monumental Montezuma, “a kind of alien with a touch of the transvestite.” Until Philippe Azoury’s slim, aphoristic, and indispensable study of the director, À Werner Schroeter, qui n’avait pas peur de la mort (2010), is translated into English, this monograph will remain essential.

-

1

See my “Magnificent Obsession: The Films of Werner Schroeter,” Artforum, May 2012. ↩

-

2

Disclosure: I gave a brief talk on Schroeter’s poor fortunes on the North American film festival circuit on a panel at the conference, which was organized by the Boston University professor Roy Grundmann, editor of the monograph. ↩