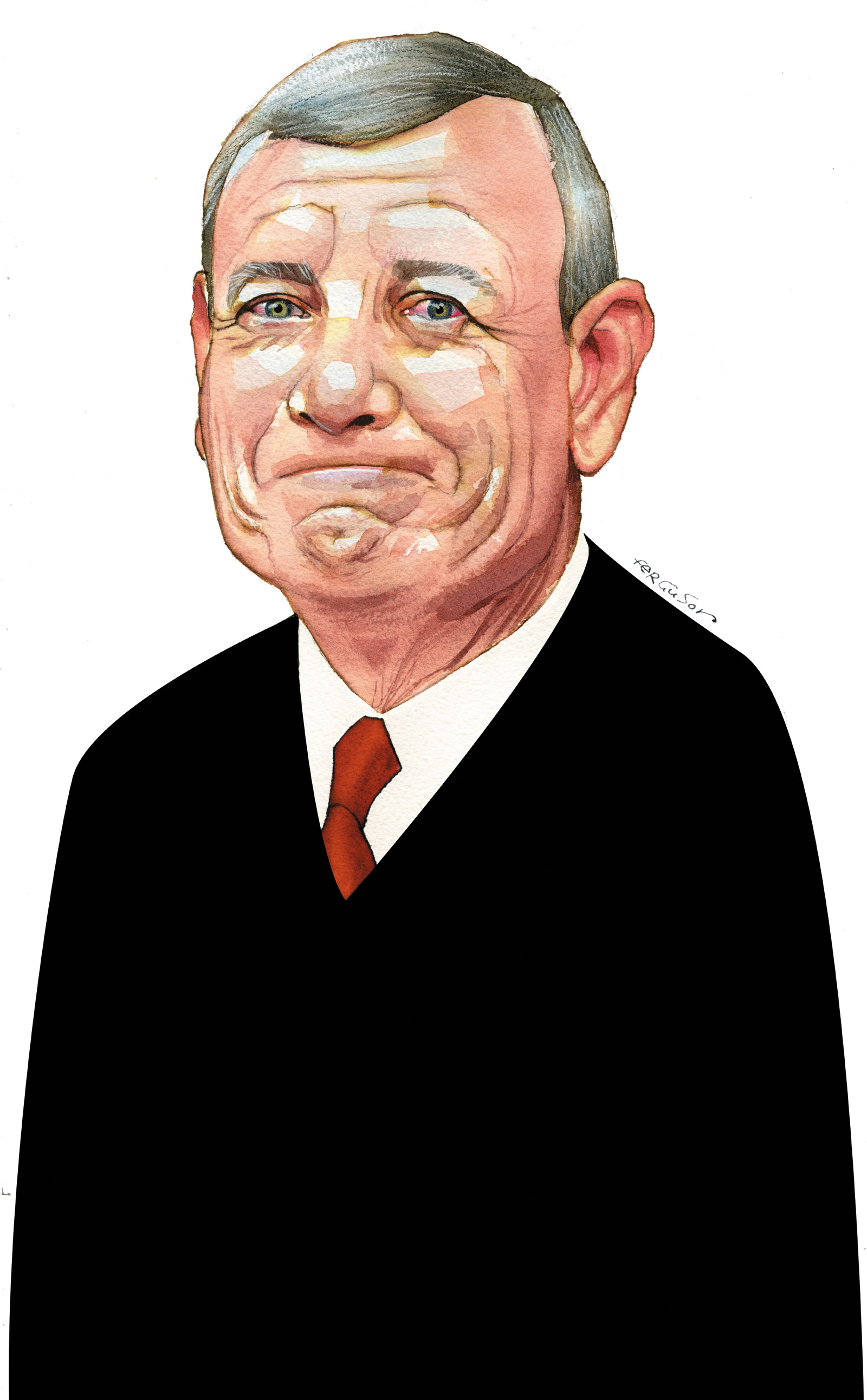

1.

The Supreme Court opened its 2018 term last October amid a highly charged political battle over the confirmation of its newest justice, Brett Kavanaugh. It closed the term in late June by issuing two major opinions about the legality of partisan efforts to rig elections and undermine the accuracy of the census. And it spent much of the time in between attempting to show that, unlike the other branches of government, the media, and most of the country, it is not defined by partisan politics. As Chief Justice John Roberts said in November in a rare public response to President Trump, who had labeled a federal judge who had ruled against him an “Obama judge,” “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

In a speech at the University of Minnesota the previous month, Roberts elaborated on the need to distinguish the Court from politicians. “We are to interpret the Constitution and laws of the United States and ensure that the political branches act within them,” he explained. “That job obviously requires independence from the political branches.” The Court’s authority rests on its legitimacy—and that legitimacy, in turn, depends on it being independent, guided by law rather than political will, and open to all sides. If one side consistently loses before the Court, why would it treat the Court as a legitimate arbiter of disputes?

The Court today has five conservative justices and four liberal ones. Since 2010, for the first time in US history, all the conservatives have been appointed by Republicans, and all the liberals have been appointed by Democrats. If the justices voted like members of Congress, almost all significant cases would be decided 5–4, with the conservatives prevailing. But the justices are not members of Congress, and that matters. It matters even more after the deeply partisan fight over Justice Kavanaugh’s nomination. A striking number of the recently completed term’s cases were decided by majorities that included at least one conservative justice joining the liberals, or at least one liberal justice joining the conservatives—almost as if the Court were seeking to reassure us that it is nonpartisan.

For example, Justice Kavanaugh sided with the four liberal justices in allowing an antitrust class action to proceed against Apple. Justice Neil Gorsuch voted with the liberal justices four times in 5–4 cases, including in striking down a federal law aimed at violent criminals. Even Justice Clarence Thomas, the Court’s most conservative justice, joined the liberals in a 5–4 decision limiting defendants’ ability to transfer class action cases filed in state courts to federal courts. Justice Stephen Breyer concurred with four conservatives to uphold an expansive interpretation of the Armed Career Criminals Act, while Chief Justice Roberts sided with the remaining liberals in dissent. And in the term’s most significant bipartisan decision, Roberts and his four liberal counterparts invalidated the Trump administration’s effort to add a question to the census asking whether members of a household are US citizens. All told, the five conservative justices voted together in 5–4 decisions eight times, but at least one conservative voted with the four liberals in eight other 5–4 decisions—meaning that the “liberal” position prevailed as often as the “conservative” position in the Court’s closest cases.

Other cases also saw surprising alliances. Justice Kavanaugh wrote an opinion finding that a prosecutor in Mississippi had engaged in racial discrimination in selecting the jury for a capital murder trial, and was joined by Roberts, Samuel Alito, and the four liberal justices. Justices Elena Kagan and Breyer joined the conservatives in rejecting an Establishment Clause challenge to a forty-foot World War I memorial in the shape of a Latin cross that was erected on government property. And in a double jeopardy case, Justice Alito wrote the majority opinion, joined by three liberals and three conservatives, while Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Gorsuch dissented. Nothing like this would ever happen in today’s Congress.

The justices seem to have gone out of their way to refute the presumption that partisan identity dictates outcomes. They did this in part by agreeing to review fewer highly controversial cases. The Court has virtually complete control over what cases it hears, so it can avoid controversy simply by denying review. It did so this term in cases involving abortion restrictions, student objections to sharing locker rooms with their transgender peers, and denials of funding to Planned Parenthood. And it delayed granting review in contentious cases asking whether federal employment law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or transgender identity, and whether President Trump permissibly rescinded immigration protection granted by President Obama under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy to undocumented persons who came to this country as minors. The Court will take up these questions next term, along with a gun rights dispute, and those cases could prove more challenging tests of whether it can rise above its own partisan divide.

Advertisement

The Court’s final decision day, on which it issued opinions on partisan gerrymandering and the census, underscored the extent to which, despite the wide range of unlikely allies this term, Chief Justice Roberts remains the fulcrum in its most significant battles. In Rucho v. Common Cause, he voted with his four conservative colleagues to rule that challenges to partisan gerrymandering are not subject to federal court review. But in the census case, he sided with the liberals to block the Trump administration’s effort to add a citizenship question to the census.

Partisan gerrymandering has become an increasing threat to democracy, as easy access to personal data enables map drawers to predict with virtual certainty how we will vote, and to draw district lines to entrench the power of the existing majority, regardless of how the electorate votes overall. In North Carolina, Republican state legislators had drawn lines to ensure a 10–3 Republican–Democratic share of congressional seats, even though the popular vote in that state is almost evenly divided. In Maryland, whose case (Lamone v. Benisek) was consolidated with North Carolina’s, the Democratic legislature shifted over 700,000 voters from one district to another in order to flip a Republican district to a Democratic district. Under these schemes, legislators effectively pick their constituents, rather than the other way around. Lower courts ruled both gerrymanders unconstitutional.

Roberts did not dispute that such practices are unconstitutional. But he declared that the problem was, in effect, too difficult for the federal courts to resolve. The central challenge is to demarcate how much partisanship is too much. Some partisan motives are inevitable as long as districts are drawn by state legislatures, as the Constitution expressly permits, and Roberts concluded that there is no manageable standard for delineating what constitutes “too much.” As a result, Roberts ruled, partisan gerrymandering must be addressed, if at all, through the political branches or the state courts. But the political branches are of course the source of the problem, and not a likely solution.

Justice Kagan wrote a convincing dissent showing that, in fact, federal courts can identify hyperpartisan outliers. Many lower courts have done precisely that, using a variety of largely consistent methods. One method relies on experts who use a computer to randomly generate thousands of maps using the state’s nonpartisan districting criteria. The experts then measure the median partisan effects of those maps, and compare the state legislature’s map to that median. Only dramatic departures from the median are considered invalid. In North Carolina, the map the Republican legislature adopted had a greater partisan advantage than any of the three thousand computer-generated maps produced by experts. “How much is too much?” Roberts asked rhetorically. “This much is too much,” Kagan replied.

In the census case, Department of Commerce v. New York, Roberts wrote for himself and the four liberals to hold that the commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, had lied in claiming that the reason he sought to add a citizenship question to the census was to aid enforcement of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). (The ACLU, of which I am the national legal director, was co-counsel for the challengers in the Supreme Court; we also submitted a friend of the court brief supporting the challengers in the partisan gerrymandering case.) Roberts noted that Ross had entered office determined to add a citizenship question, even though the Census Bureau told him that doing so would undermine the accuracy of the census by discouraging immigrant families from responding. In search of a justification, Ross shopped the idea around to three separate federal agencies, including the Justice Department, but initially got no takers. He finally personally interceded with Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who agreed to request information about citizenship in the name of enforcing the VRA, a justification concocted by the Commerce Department.

The request was unfounded. The VRA had been enforced for the fifty-four years of its existence without asking about citizenship on the census, and in any event the Census Bureau could get more accurate citizenship information using polling and existing government records, such as Social Security files. After the case was argued in the Supreme Court, new evidence emerged that the leading Republican redistricting strategist had advised that asking about citizenship would aid “Republicans and non-Hispanic Whites,” and had drafted the first version of the VRA rationale for the Commerce Department. This was too much for Roberts, who concluded that the VRA rationale was a pretext, and that an agency cannot lie about its reasons for pursuing a course of action if judicial review is to be meaningful.

Advertisement

The two decisions point in opposite political directions. The gerrymandering decision is seen as aiding Republicans, at least in the short term, principally because they control more state legislatures at the moment. But gerrymandering can be done by both parties, as the Maryland and North Carolina cases before the Court illustrated. The census decision, by contrast, rejected a Trump administration initiative that would have led to undercounting—and therefore reduced representation and federal funding—in communities with significant immigrant populations, which are disproportionately Democratic. By issuing the two decisions together, the Court sent a message that it is not partisan in its rulings. But that message was possible only because of Roberts’s votes, as all the other justices voted in both cases consistently with the partisan identities of the presidents who appointed them.

And while there is much to criticize in Roberts’s gerrymandering decision, as Kagan’s tour-de-force dissent makes clear, the strongest prudential argument in his favor is the risk that, if courts start reviewing such claims, they would be dragged into the partisan muck. Rulings in such cases will inevitably aid one or the other political party. Quoting Justice Anthony Kennedy, Roberts writes:

With uncertain standards, intervening courts—even when proceeding with best intentions—would risk assuming political, not legal, responsibility for a process that often produces ill will and distrust.

Perhaps for this reason, even before this decision, the Supreme Court had never found a partisan gerrymander to be impermissible. The decision is less a radical revision of doctrine than the closing of a door that was only barely open in the first place. Thus the result in even the Court’s most partisan dispute of the term finds its best defense in the notion that the Court should stay out of such disputes to protect its nonpartisan character. The question Roberts did not answer is whether keeping the Court’s hands clean is worth the cost of a fundamentally broken democratic process.

2.

This past term, then, the Court managed for the most part to avoid partisan fracture. Though that may seem surprising, it is actually nothing new. For most of its existence, the Court’s rulings have not been defined by party politics. From 1790 to early 2010, of 397 decisions identified as important by the Guide to the US Supreme Court and that had at least two dissenting justices, only two were divided along party lines. Even the Court’s most controversial cases have been decided by “mixed” majorities. Miranda v. Arizona was decided 5–4, with two Republicans and three Democrats in the majority, and two Republicans and two Democrats in dissent. Roe v. Wade, anathema to most of the Republican Party today, was decided 7–2, with five Republicans and two Democrats joining the majority, and one justice from each party dissenting. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed much of Roe against a Reagan administration effort to overturn it, four Republicans and one Democrat were in the majority, while three Republicans and one Democrat were in dissent. Brown v. Board of Education was unanimous. And in recent decades, the votes of Republican justices have been critical to decisions upholding affirmative action, invalidating public support of religion, expanding privacy rights, protecting flag burning, recognizing LGBT rights, and restricting the death penalty.

Individual justices have often voted in ways that part company with the ideological commitments of the party of the president who appointed them. David Souter, Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens, Earl Warren, and William Brennan were all appointed by Republican presidents but proved to be liberal justices. Tom Clark and Byron White, appointed by Presidents Truman and Kennedy, respectively, were relatively conservative. And Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, both appointed by Ronald Reagan, were considerably less conservative than many Republicans liked.

Since Kagan replaced Stevens in 2010, the justices’ ideologies for the first time in history have aligned precisely with the party of the president who appointed them. Yet even in this period, the Court’s results cannot be explained on simple partisan grounds. During the eight terms between 2010 and 2017, Democrat-appointed justices were more often in the majority than Republican appointees in three terms, Republicans were in the majority more often in four terms, and one term was a tie.

But preserving this independence has grown far more difficult, for reasons ably explored by Neal Devins and Lawrence Baum in The Company They Keep, a carefully argued and disturbing portrait of how partisan politics threaten to engulf the Court. The country, of course, has become increasingly divided in recent times. “In 1994,” Devins and Baum write, “23 percent of Republicans were more liberal than the median Democrat and 17 percent of Democrats were more conservative than the median Republican.” In 2017 those figures were 1 percent and 3 percent, respectively. The press and social media are increasingly segmented along partisan lines. And the very fact that the country is so evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans makes it all the more imperative for each side to put party loyalty above all else, because small shifts can lead to decisive transfers of power.

Consider how the nominations process has been politicized. In 1986 and 1987, Justices Antonin Scalia and Kennedy were confirmed unanimously. In 1993 Ginsburg, who expressed strong support for the right to abortion, was confirmed 96–3. With the exception of Robert Bork, who was defeated by a largely party-line vote, even the rare rejections were generally bipartisan. When the Senate in 1970 refused to confirm President Nixon’s nominee, Harrold Carswell, because he had supported racial segregation, thirteen Republicans and thirty-eight Democrats voted against him, while seventeen Democrats and twenty-eight Republicans supported him.

In recent years, by contrast, Justice Kagan’s nomination was opposed by all but five Republicans, and Justice Kavanaugh’s by all but one Democrat. Even before knowing whom Trump would name to replace Justice Kennedy, conservative groups pledged to spend millions of dollars to support the nominee, and liberal groups pledged millions in opposition. When Kavanaugh’s nomination was officially announced, the organizers of the Women’s March issued a press release condemning him as “extremist,” but forgot to replace “XX” in the text with his name.

It is hard to imagine how these trends could not affect the Court. As Justice Benjamin Cardozo once wrote, “The great tides and currents which engulf the rest of men, do not turn aside in their course, and pass the judges by.” Devins and Baum argue that partisan influence operates not directly but via the elite communities with which the justices associate. They posit that the justices are more likely to be influenced by elite opinion than by general public opinion, for a number of reasons. First, the justices are themselves part of the elite; they all attended either Harvard or Yale Law Schools, for example. Second, they care deeply about their reputations, which are largely determined by their elite peers. Third, the general public does not follow the Court’s decisions closely, if at all; the legal and media elites, by contrast, pay close and sustained attention.

Legal, academic, and media elites were, until recently, relatively united in favoring civil liberties and civil rights—more so than the public at large. Devins and Baum posit that this may explain why so many Republican-appointed justices have voted as liberals or moderates. In 2003 the conservative political commentator Thomas Sowell complained that, for the justices, “all the influences and incentives are to move leftward. That is how you get the applause of the American Bar Association, good ink in the liberal press, acclaim in the elite law schools and invitations to tony Georgetown parties.”* (Sowell is believed to have coined the term “the Greenhouse effect,” after New York Times Supreme Court reporter Linda Greenhouse, to describe the phenomenon.)

By 2003, however, conservatives were already well on their way to altering the leftward tendency of elite influence. As Steven Teles laid out in The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement (2008), conservatives responded in the 1980s to what they saw as a legal and academic elite that did not reflect their views by founding the Federalist Society, a network of conservative students, lawyers, and judges; advocating originalist and textualist modes of judicial interpretation; and promoting a conservative economics-based approach to law and legal regulation in law schools and educational seminars for judges. Today, the Federalist Society is the principal gatekeeper for Republican judicial appointments; President Trump has effectively outsourced judicial nominations to the group. All five Republican justices have close Federalist Society ties and the group has become the mainstay of the conservative legal elite. Meanwhile, Rupert Murdoch has ensured that there is a robust conservative media elite as well. And while faculties at top law schools remain overwhelmingly liberal, conservative scholars have increasingly assumed positions there as well. As a result, Devins and Baum contend, the Court’s partisan divisions are likely to be exacerbated, not offset, by the justices’ desire to be respected by their now-divided communities of elites.

3.

The future course of the Court will be determined by many forces, including the politics of the country at large. The Court historically has only rarely departed sharply from where the country’s politics lie. And it is still too early to assess how Justices Kavanaugh and Gorsuch will vote in many matters. But much is likely to turn on Chief Justice Roberts. As Joan Biskupic’s invaluable biography, The Chief, shows, Roberts is at once a committed Republican with very conservative policy preferences and ties to the conservative community, and an institutionalist who cares deeply about the nonpartisan character of the Court. He is not, to be sure, the only justice who values judicial independence, open-mindedness, and legal craft. But because, as the chief justice, he has a special responsibility for the institution, Roberts may feel the desire to avoid partisanship or its appearance especially acutely.

That, at any rate, may be the best explanation for the fact that, at critical times, his decisions have been less reflexively conservative than those of his current Republican colleagues. Roberts’s conservative pedigree is every bit as solid as theirs. In his first job after clerking for Justice William Rehnquist, he served as special assistant to Attorney General William French Smith and was a passionate advocate for the Reagan administration’s opposition to Voting Rights Act reforms and other remedies for racial discrimination. As a deputy solicitor general in the George H.W. Bush administration, he helped write a Supreme Court brief making it easier for schools to escape desegregation decrees. He was a critic of Roe v. Wade and led the successful defense of the Bush administration’s effort to deny information about abortion to indigent pregnant women who rely on federally funded family planning services. As a private practitioner, he appeared on the MacNeil-Lehrer NewsHour to defend a Supreme Court decision striking down federal programs that favored minority contractors.

As a justice, Roberts has almost always sided with the conservatives. He has voted against affirmative action and recognition of same-sex marriage. He has consistently sided with business interests against consumers and workers. He has voted to uphold restrictions on abortion, to recognize gun rights, and to approve government funding to churches. He wrote the Court’s opinions striking down the single most effective provision of the Voting Rights Act and a Seattle program that sought to maintain diversity in K-12 schools. If this is where we have to look for moderation, it is far from clear that we will find it.

But now that Justice Kennedy has retired, the question is whether Roberts, or for that matter anyone else on the right, will take steps to ensure that the Court remains open to all. As long as Justice Kennedy did so, there was less need for Roberts to. But if no one in the Republican majority is willing to be a moderating influence, the Court will veer sharply to the right, far out of step with the public at large.

At least on occasion, Roberts has shown that he is willing to part company with his colleagues on high-profile issues and to incur the wrath of conservatives. Biskupic devotes a lengthy chapter to his decision in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, a constitutional challenge to the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In that case, he reportedly initially voted—at the conference that immediately follows oral argument—to strike down as beyond Congress’s power the law’s “individual mandate,” which required citizens to purchase health insurance or pay a tax. But while writing the opinion, he changed his mind, and ultimately voted with the four liberal justices to uphold the law as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to impose taxes. Biskupic concludes that “he acted…more like a politician” than a judge. Many conservatives have faulted him for doing so, and many liberals have praised him.

But it is just as possible that he concluded, while trying to write the opinion, that under the Court’s precedents, Congress’s power to tax, which is virtually unlimited in scope, encompassed the exaction of a tax from those who failed to purchase insurance. The fact that he changed his mind does not mean that he abandoned his best view of the law in favor of a “political” outcome. It may simply reflect a commitment to an open mind, and to being guided by the law, even when it took him to a place he did not expect.

Former Reagan administration solicitor general Charles Fried has praised Roberts for his ACA decision,

because it is evident that in this most fraught, pressured, and political of cases, he tried to do the right thing and was willing to pay the price in the esteem of those with whom he was in closest political, doctrinal, and temperamental agreement.

Here, in short, Roberts broke from the partisan peer pressure that Devins and Baum so vividly describe and decry.

The same can be said of Roberts’s vote in the census case. And in two votes this term on emergency requests for relief, he also sided with the liberals. In the first, he voted to grant a temporary injunction against a Louisiana abortion restriction that a lower court had sustained, even though he had dissented just a few years earlier from a decision striking down a similar law in Texas. And he also voted to deny a Trump administration request to lift an injunction against a policy that would have denied asylum to anyone who had not entered the country lawfully, in the face of a statute providing that asylum is available to all those facing persecution at home, whether they enter lawfully or not. In all three cases, Roberts cast the deciding vote, as his four Republican colleagues dissented.

Fried is right that Roberts deserves credit; the judicial creed demands independence not only of one’s party but of one’s closest friends. Yet there is another feature of the elite worlds in which the justices travel that rewards such independence and may moderate partisan influence. As much as legal elites may disagree these days, they do share some values—in particular, the notion that law should be distinct from politics, and that judges should decide cases by appeal to logic and precedent rather than personal or partisan ideology. As Devins and Baum put it, “the Supreme Court is a court, and the Justices respond to expectations among legal elites that they will act as legal decision makers.”

These expectations are held in common by the Federalist Society on the right, the American Constitution Society on the left, the American Bar Association in the middle, and, perhaps most importantly of all, the “Supreme Court bar”—the small group of super-elite lawyers who regularly appear before the Court. This group in particular prides itself on collegiality and respect for legal craft, and is committed to a judicial ideal that honors reasoned argument above partisan identity. Indeed, Roberts, who before becoming a judge was one of the most highly regarded members of the Supreme Court bar, put it in just these terms when asked at his confirmation hearings about judicial independence: “If it all came down to just politics in the judicial branch, that would be very frustrating for lawyers who worked very hard to try to advocate their position and present the precedents and present the arguments.”

If the Supreme Court is to remain above the partisan maelstrom, it will be because of the bipartisan appeal of those traditional ideals. In no one are they more deeply ingrained than in Chief Justice Roberts, a traditionalist to his core. Skeptics often dismiss the distinction between law and politics, but today’s Court underscores the critical importance of the norms of independence that Roberts has championed. That may be a slender reed—but it’s better than the alternative. Just look at Congress.

This Issue

August 15, 2019

The Ham of Fate

Burning Down the House

Real Americans

-

*

Thomas Sowell, “Justice Kennedy Goes Soft on Crime,” Columbus Dispatch, August 13, 2003. ↩