“Civility,” Keith Thomas notes in this absorbing book, “was (and is) a slippery and unstable word.” “Civil” and “civilian” evoke the social life of a people not under military rule, the world of the civitas—the organized community—the only place, according to Aristotle and Cicero, where the good life is possible. While “courtesy” relates to the values of the court, “civility,” Thomas writes, is “the virtue of citizens”: in his Dictionary (1755), Samuel Johnson defined it as both “politeness” and “the state of being civilized.” Thomas explores the understanding and use of the term in England from 1500 to 1800, when it referred both to manners in daily life and manners as mores: the customs and attitudes of the allegedly civilized nation as a whole.

In its wider sense, the ideal of civility was orderly government, with a populace accepting its laws and prescribed moral standards as well as adhering to the hierarchical structure of society and the strict but subtle dictates of class and decorum (the chief one being “know your place”). In Britain, “civil government” reflected the interests of the moneyed classes: the protection of private property and the value of trustworthiness, essential for a credit-based economy. In time, the idea of civility also came to embrace an interest in the arts and sciences, and—at least in theory—religious toleration, open debate, and the freedom to disagree.

Beyond civility, which entailed living peaceably together in “quietness, concord, agreement, fellowship, and friendship,” as the Elizabethan schoolmaster Richard Mulcaster put it, lay the more nebulous term “civilization.” Its meaning of a total culture had hardly entered the language by the mid-eighteenth century. Instead, throughout the period covered by Thomas’s book, it more often implied a process, like education. As such, the “civilizing” mission, directed against so-called barbarians, could be used to justify oppression and violence, in Britain and abroad.

Since classical times, “barbarism” had been presented as the opposite to “civility.” To the Greeks the barbaroi, non-Greek speakers, not only lacked linguistic skills but also moral qualities—they were cruel and intemperate. The Romans, fearing barbarians at the gates, also considered the tribes outside their empire brutal and uncultured. In medieval Europe, the division shifted to encompass differences of faith: the opposition, in Chaucer’s words, between “christendom and hethennesse.” The religious definition—the barbarian as pagan—lingered on, combined with a more general sense of barbarism as “rude,” “wild,” “uncultured” behavior. But in every case, across the ages, “civility” is where the speaker stands: the barbarians are those who are not “us.”

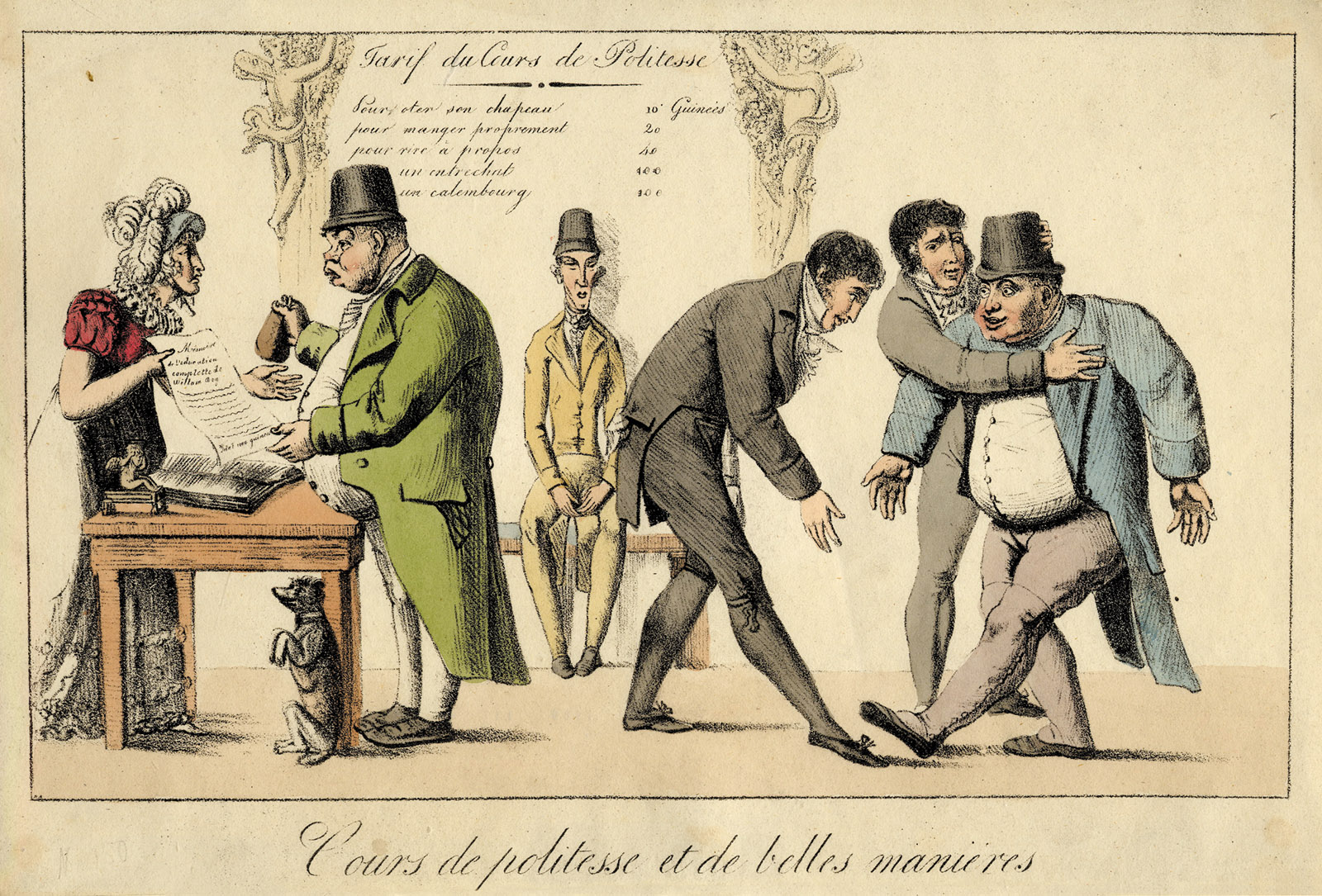

By exploring these polarities, Thomas paints an extraordinary picture of the values and social relationships of Britain, specifically of England, and moves outward to consider the changing global setting of trade and colonialism, and the way that the language of “civilization” would underpin the imperialism of the nineteenth century. This inquiry, he notes, is “part of an attempt to construct an historical ethnography of early modern England which has occupied me on and off for many years.” In its reach and riveting detail, it rivals his early studies of changing attitudes, Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971) and Man and the Natural World (1983), wide-ranging books that thrilled and informed in equal part. In them the apparently trivial often turns out to reveal underlying attitudes; in the preface to In Pursuit of Civility, Thomas quotes the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who claimed that one could infer “a whole cosmology, an ethic, a metaphysic, a political philosophy, through injunctions as insignificant as ‘Stand up straight’ or ‘Don’t hold your knife in your left hand.’”

The excitement, and occasional shock, of In Pursuit of Civility come partly from Thomas’s technique. He immerses himself in the past. Because his interest is in the multifaceted mentality of a people and a period, the works he studies are varied—a sermon, a diary, a play, a recent monograph, a legal treatise, a recipe book. In a 2010 essay, he described his method: reading everything that seemed relevant, marking sources, copying extracts and quotations, then cutting up the papers containing these notes, dividing them by subject, and placing the fragments—with newspaper cuttings and other material—in labeled envelopes:

The envelopes run into thousands…. Some of them get loose and blow around the house, turning up months later under a carpet or a cushion. A few of my most valued envelopes have disappeared altogether. I strongly suspect that they fell into the large basket at the side of my desk full of the waste paper with which they are only too easily confused.*

(In a letter responding to this piece a former member of his research seminar, William Lamont, remembered raising a question with him at breakfast: “He instantly went to a side room and came back with a fat envelope marked ‘Muggletonians and animals.’ He scattered its contents on the kitchen table. I found what I needed, if my memory is correct, at a point somewhere between the toast and the marmalade.”)

Advertisement

The gathering of quotations and anecdotes “from a mass of casual and unpredictable references accumulated over a long period” creates a layered counterpoint of voices, or rather a palimpsest in which later writings bear visible traces of earlier forms. In his engagingly self-deprecatory description of his method, Thomas pretends to be a dinosaur from the pre-Internet age. In fact, at eighty-six, as the ninety pages of notes to In Pursuit of Civility show, he hunts the Web as well as the library. In the introduction he assumes, too, the mantle of puzzled foreigner:

As a Welshman, and therefore something of an outsider, I have tried to study the English people in the way an anthropologist approaches the inhabitants of an unfamiliar society, seeking to establish their categories of thought and behavior, and the principles that governed their lives.

An outsider anthropologist he may be, but his long career at Oxford suggests a supreme insider too: he has been a fellow of All Souls College and then of St. John’s College, professor of modern history, president of Corpus Christi College, and pro-vice-chancellor of the university. Commenting on how servants became more ostentatiously formal than their masters—a pattern that makes me think of Malvolio—he adds, “as can be seen in some modern Oxford senior common rooms, where black-coated butlers wait impassively on gesticulating Fellows clad in sweaters and jeans.”

The first envelopes to spill onto these pages trace the evolution of manners in the more limited sense. In the sixteenth century a vast prescriptive literature on manners was published in Britain, often following Continental models: Erasmus’s advice to children appeared in English in 1532, Castiglione’s The Courtier thirty years later. Politeness, or “polish,” eased the way in Jacobean society, and was reinforced in the reign of Charles II by fashionable French models and at the start of the eighteenth century by the advice of Addison and Steele in the Spectator and Tatler. Acquiring “manners” was a deft strategy for merchants and financiers wishing to be accepted in high society, a way of presenting themselves as part of an elite far removed from trade and the mob. Deportment, speech, gesture, and posture marked out the gentleman. You had to know how to enter and leave a room, avoid scratching, wriggling, and whistling, and never appear hurried. (A drawling laziness was conjured by Nancy Mitford as late as 1955, in her ironic definition of U and non-U—upper- and middle-class—ways: “Any sign of haste, in fact, is apt to be non-U, and I go so far as preferring, except for business letters, not to use air mail.”)

It was a difficult line to tread. Dancing was a required skill, but dancing too well was affectation. Control of the emotions was essential in men—no loud laughter, no weeping except on public occasions such as the performance of a tragedy at the theater or a royal funeral, and even there only in moderation. A talent for conversation was a must, but there should be no mention of business (embarrassing for guests pretending not to be tradesmen) or of the weather, wives, children, or clothes. You could be witty but had to stay cunningly inoffensive. In 1725 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote of Sarah Churchill, the Duchess of Marlborough, not her favorite person, “We continue to see one another, like two people that are resolved to hate with civility.”

Thomas rightly stresses the body as the site of state power and punishment as well as of the fundamentals of ordinary living. But bodily manners were confusing. While politeness at table proscribed cramming the mouth or licking the dish, in the seventeenth century sharing was still the rule. People did not have their own cutlery until the middle of that century or later, and even in the eighteenth century they brought their own knives. In 1816 an Essex farmer, following the old ways, “carving a piece of fowl for himself ‘unluckily helped himself to a gentleman’s middle finger.’ This accident, it seems, was ‘occasioned by the eagerness of the company, who all had their hands in the dish at the same time.’”

Shared eating was one thing, shared defecation another. In 1732, visiting Scarborough spa, Sarah Churchill found a room with more than twenty holes, with drawers underneath them and a heap of leaves at the door for the women to use. Appalled, she left at once. Thirty years later, visiting London, Casanova was astonished to see people shitting in the streets, turning their backs to passersby as if that made them invisible.

Advertisement

As a result spas and city streets felt far from polite. And rule books were never a guide to actual behavior. The “good breeding” of the eighteenth century, Thomas notes,

was accompanied by sexual libertinism, heavy drinking, brutal sports, bawdy and scatological humor, and scurrilous gossip. The values of civility and politeness were all-pervasive in early modern England, but their influence on the behavior of the upper classes was never complete.

Yet the upper classes continued to expect deference. As Swift saw it, a principal point of good manners, of making people feel at ease, “is to suit our behaviour to the three several degrees of men: our superiors, our equals, and those below us.” The upper ranks should be affable and condescending (not a pejorative term)—practical virtues that would win the loyalty of subordinates, tenants, and voters. The gentlefolk and inhabitants of country towns were acknowledged to be moderately cultivated, since they had assembly rooms, coffeehouses, clubs, and societies. Here politeness proved a useful means for small tradesmen to ingratiate themselves with wealthy customers, and the division was between the “genteel” and the “vulgar,” though one had to avoid overgentility, which could topple into affectation and invite ridicule.

At the bottom of the social scale, however, people had little interest in or time for “civility,” which required leisure, money, education, houses, and servants. In the late seventeenth century Edward Chamberlayne’s annual handbook, Angliae Notitia, described the nobility, gentry, and leading tradesmen as “well-polished,” but the “common sort” as “rude and even barbarous.” Country folk were referred to as “Indians,” farm laborers as “‘barn-door savages,’ ‘country hawbucks,’ mannerless ‘gubbins’”; and Highlanders or Cornish peasants were regarded as near savages. More barbarous still were the squatters in fens and forests, the wandering poor, and the miners, uniformly written off as brutal. Upper-class families were advised to avoid clownish rustics at all cost. “Peasantry,” warned one eighteenth-century writer, was “a disease like the plague, easily caught by conversation.”

It’s heartening, amid the long chorus of disdain, to find Dr. Johnson declaring that “the true test of civilization” was “a decent provision for the poor.” Yet they too had their code of manners, of honesty, decency, communal celebration, and mutual support. Observers noted with fascination, even envy, how spontaneous the common people were in expressing their feelings: open in laughter, threatening in anger, colorful in language. This assumption surely lies behind Wordsworth’s explanation in the preface to the 1800 edition of the Lyrical Ballads that “humble and rustic life was generally chosen, because, in that condition, the essential passions of the heart find a better soil in which they can attain their maturity, are less under restraint, and speak a plainer and more emphatic language.”

Elizabethan and Jacobean thinkers divided nations, as well as classes, into the civil and the barbarous. The Irish and the North American Indians, for example, must be “civilized,” by force if need be, to make them into “complaisant” neighbors. Early modern jurists represented humanity as bound together by a universal law of nature, discernible by reason rather than divine revelation. Once one had accepted that there were principles of natural justice and rules, “established,” according to Sir William Blackstone, “by universal consent among the civilized inhabitants of the world,” then nations who broke, or did not know, these universal principles could be labeled barbarians and treated as such—often with unblinking ferocity.

Theories of “natural justice” had positive applications in establishing rules of warfare and forbidding the enslavement or killing of prisoners, but these rules could always be flouted when the enemy behaved “barbarously.” The depiction of sects or nations as “cruel” (a quality of barbarism) also legitimized violent responses, such as Cromwell’s bloody retaliation eight years after the rebellion of Ulster Catholics in 1641. And while protests brought an end to torture under the royal prerogative after the reign of Charles I, and the Bill of Rights outlawed all “cruel and unusual punishments” in 1689, sentences in English courts still included hanging, branding, pillorying, and flogging. None of these, of course, was barbarous.

Barbarians and savages (even lower on the scale) were easy to spot. Entire tribes and nations, it was said, shared the defining characteristics. They were dirty and they stank; they wore odd clothes or none at all; they ate weird food such as insects and reptiles; they practiced polygamy and ignored the rights of women—a hypocritical accusation, given the position of women in Europe. They were ruled by despots or had no organized government at all—or so it was assumed. They were nomads rather than settled farmers and traders, and they lacked all the skills of politeness: accepted manners, literacy, numeracy, printing, and a concern for intellectual inquiry.

There were some difficulties here. The Turks, for example, although pagan and cruel, were acknowledged to be intelligent, literate, and (to wide surprise) scrupulously clean, and the cultures of China and India commanded some respect. But all in all, European superiority was evident. This prejudice lasted a long time: the League of Nations, founded in 1920, was proud to include only “civilized” nations and regarded one of its tasks as spreading civilization to the rest of the world. In a footnote, Thomas comments, “This did not prevent the League from recognizing Soviet Russia, Nazi Germany, and Fascist Italy.”

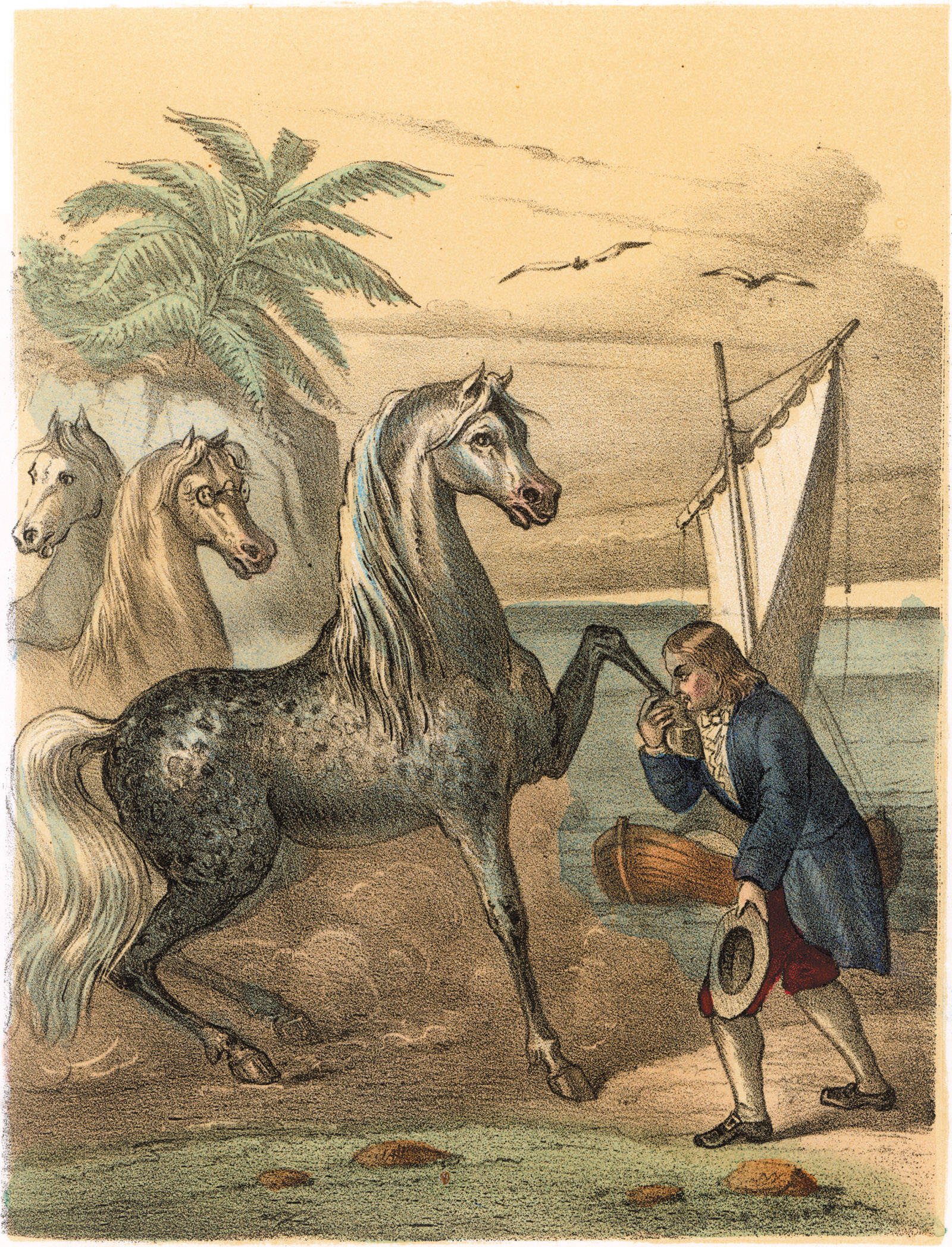

If politeness was judged crudely by distance and difference, it was also measured by history. The dawn of civility, it was argued, came when agriculture replaced hunting and herding. Look at countries that live by keeping cattle, Edmund Spenser suggested, “and you shall find that they are both very barbarous and uncivil, and also greatly given to war.” In the Scottish Enlightenment, Lord Kames and Adam Smith traced the climb to politeness in stages, through the Ages of Hunters, Shepherds, and Agriculture to the current Age of Commerce, with its laws, flourishing arts, and “softening” of manners. In France, defining a similar progression from hunting and gathering to pastoralism and trade, the economist Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot reduced this to three basic stages: savagery, barbarism, and civility.

Groups viewed as “stuck at an earlier phase of development,” like the Highland Scots and native Irish, were prime targets for the civilizing project. Exporting civility was a duty, and it is explored in the most illuminating and disconcerting section of Thomas’s book. Repeatedly, invaders and their supporters cited “the law of nature and humanity” to back the possession of land that “uncivilized” natives left untilled. Supporting the settlement of Virginia, preachers and lawyers argued that the English had been chosen by God to evict Indians and introduce better agricultural methods, making the land a hundred, “perhaps a thousand” times more productive. There was much fudging: on one hand, as barbarians, the Indians had no land rights: on the other, the common use of purchase to acquire land implied that they did, even if they did not understand the contracts.

Beyond that muddle, successful land-grabbing meant getting rid of the current inhabitants, and while men like Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes ruled that settlers should not be allowed to exterminate an existing population, others disagreed. James I ordered a Scottish noble to “extirpate and root out” three clans from Skye and replace them with “civil” people; Milton supported Cromwell’s crushing of Ireland as a “civilizing conquest”; plantation owners in the West Indies advocated the wholesale “extirpation” of the Caribs as “barbarous savages.”

From the late seventeenth century, Enlightenment apologists began to propound theories of racial difference to support such arguments, claiming that rather than a single humankind, there were at least four or five species ranging in capabilities, with nonwhites being “naturally inferior.” My heart sank to find the humane and rational David Hume proclaiming this and adding that “there never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white.” It is more jolting still to find slavery identified as a civilizing phase. Thomas quotes the poet John Taylor: “Through slavery and bondage many people and nations that were heathens and barbarous have been happily brought to civility and Christian liberty.”

Thomas’s exposition through quotation can be dizzying, especially when voices ranging across three hundred years are juxtaposed in a single paragraph or page. But this layering is a powerful way of showing how prevailing notions endure, despite shifts in emphasis. Continuity does not, of course, mean consensus. Thomas takes care to bring in dissenting voices, critics, and satirists like Swift. Gulliver explains European culture to the Houyhnhnms: “If a prince sends forces into a nation where the people are poor and ignorant, he may lawfully put half of them to death, and make slaves of the rest, in order to civilize and reduce them from their barbarous way of living.”

We can follow the slow emergence of cultural relativism from Montaigne’s Essais of 1580–1588 onward. In Dryden’s Indian Emperour (1665), Cortez answers the accusation that in Mexico all is “untaught and savage”:

Wild and untaught are terms which we alone

Invent, for fashions differing from our own.

Travel and scholarship gradually reduced prejudices and inspired the acceptance, in the late eighteenth century, that there were indeed different “civilizations.” But this dawning pluralism, sighs Thomas, “was quickly overshadowed by a new and accelerated phase of Western imperialism, which represented itself as advancing ‘Civilization’ in the singular.”

In Britain, people in the provinces began to resist the imposition of metropolitan habits and fashions, which they saw as synonymous with insincerity, while groups like the Quakers posed radical challenges to the rules of deference and address, regarding “the hypocritical obsequiousness of polite speech as an enemy to ‘the truth, simplicity and honesty of the heart.’” Thomas’s detailed examination of the subject takes us to the end of the eighteenth century, by which time, he believes, the link between polite manners and private morality had been broken forever. Leaping forward, he notes how hierarchical, aristocratic notions of civility were slowly undermined as the growing economy created a new, influential class of industrialists and financiers, an expanding labor market brought more social mobility, and the extension of the franchise encouraged the questioning of symbols of power. Over time, “civility” shifts and changes, its definition still depending on the speaker—the true barbarisms of the twentieth century, including the Holocaust, harked back to an earlier notion that the laws of war could be suspended in conflict with “barbarians.”

But does the term “civility” have any meaning today, in an age of global capitalism and struggles for human rights, equality, and diversity? Thomas notes that in the eighteenth century Hume and Burke both asserted that manners, in the broad sense of “habits and customs,” were more significant than laws in controlling antisocial behavior. By the late twentieth century, however, “the constraints of civility proved inadequate to enforce new ideals of equality and diversity,” and since then societies have increasingly turned back to the law and to formal procedures of accountability, legislating on human rights, race relations, sexual harassment, the treatment of children, and public nuisances like smoking—or catcalling.

But although informal codes can no longer be relied on, we still need them if we are concerned about “civility” in the everyday sense, as a means of allowing people with different beliefs and attitudes to live in peace side by side. Civility here need not be deferential; it can generously embrace fair-mindedness, readiness to listen, and respect for others. “Not until it is accepted that civility means tolerance of difference,” writes Thomas, “whether ethnic, religious, or sexual, can it be expected to protect humanity from further disasters.” A civilized ideal, hard to achieve but vital to aim for.

This Issue

August 15, 2019

The Ham of Fate

Burning Down the House

Real Americans

-

*

“Diary,” London Review of Books, June 10, 2010; Letters, July 8, 2010. ↩