Celebrity culture is not new, even if it often feels that way. Henry James greatly admired Sarah Bernhardt when he first saw her on the Parisian stage in 1876, but what he witnessed when she arrived in London three years later was “the success of a celebrity, pure and simple”—a success that in James’s eyes had very little to do with her gifts as an artist. “It would require some ingenuity,” he wrote, “to give an idea of the intensity, the ecstasy, the insanity as some people would say, of curiosity and enthusiasm provoked by Mlle. Bernhardt.” If “the trade of a celebrity” had not already been invented, according to James, Bernhardt “would have discovered it. She has in a supreme degree what the French call the génie de la réclame—the advertising genius; she may, indeed, be called the muse of the newspaper.” Though she had yet to make her first tour of his native land, he was confident of the reception she would find: “She is too American not to succeed in America.” Like James’s other remarks on the actress’s newfound “trade,” this was not intended as a compliment.

Bernhardt would in fact make ten triumphant tours of the United States, performing not only in obvious places like New York, Chicago, and Boston, but in comparatively provincial towns like Salisbury, North Carolina, and Battle Creek, Michigan. On the first of her four “farewell” tours to the US in 1905–1906, her stops in Texas alone included Dallas, Waco, Austin, San Antonio, and Houston. In Kansas City, she ordered a custom-made tent with seating for five thousand and raked in nearly $10,000 for a performance in the Convention Hall before the tent could be finished—“the largest single night receipts from a dramatic engagement ever known in the history of the stage,” according to a contemporary account in Theatre Magazine. Her European tours took her as far afield as Turkey and Russia; she also performed in Egypt, Australia, New Zealand, and multiple countries in South America.

Even when she was not on stage, Bernhardt managed to keep herself in the spotlight: arranging to be photographed sleeping in a coffin, for instance, or chartering a hot-air balloon to fly over Paris and then following up with a book ostensibly narrated by her balloon chair. Both these well-publicized stunts took place as her fame was first accelerating in the 1870s, but her genius for self-promotion scarcely flagged in the decades that followed. By the time of her death in 1923, she was clearly the most famous actress in the world. A crowd estimated at a million lined the streets of Paris for her funeral, anticipating those who would gather for Princess Diana in London more than seventy years later. Captured by a Pathé newsreel, Bernhardt’s mourners continue to pay tribute to her—as do Diana’s, of course—on YouTube.

Bernhardt has the starring role in Sharon Marcus’s The Drama of Celebrity, while she only makes a cameo appearance in Susan J. Douglas and Andrea McDonnell’s Celebrity: A History of Fame, but both books choose to begin their accounts in the nineteenth century, when democratization and the rise of mass media gave a distinctively modern twist to the age-old quest for fame. Neither book offers an explicit definition of celebrity, but both agree that the distance between the famous and the rest of us has been radically narrowed by celebrity culture. Marcus distinguishes celebrities from people famous only after their death, while Douglas and McDonnell emphasize the “widespread visibility” of the modern celebrity, as opposed to the “aura” of remoteness that attended fame in previous eras, and the fundamental contradiction that results: celebrities are special persons who are also expected to be just like everyone else. Both books invoke many of the same predecessors, from Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944) to Erving Goffman’s studies of everyday performance and Leo Braudy’s The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History (1986).

The authors’ investments in celebrity are quite different, however, as are the disciplinary backgrounds they bring to bear on its history. (Marcus is a scholar of comparative literature; Douglas and McDonnell, of communication and media studies.) While Marcus puts the global nineteenth century at the center of her story, Douglas and McDonnell focus almost exclusively on technological change in the United States and its implications for celebrity culture. Though they open Celebrity with the Astor Place Riot of 1849, in which competing fans of the British actor William Charles Macready and the American Edwin Forrest battled it out on the streets of New York, Douglas and McDonnell have comparatively little to say about the theater (apart from vaudeville and minstrelsy), while the bulk of their book concerns developments in mass media from early film to Instagram and Twitter.

Advertisement

For Marcus, on the other hand, the career of an actress born in 1844 not only inaugurates modern celebrity but exemplifies it. Though Marcus acknowledges in passing that celebrity culture, especially the theatrical kind, really originated in the eighteenth century, her decision to focus on Bernhardt—rather than, say, Sarah Siddons (1755–1831)—pays tribute to the Frenchwoman’s mastery of global media that were scarcely available when her great British predecessor held the stage. At the same time, Marcus wants to resist the deterministic narratives so often associated with scholarly approaches to her subject, particularly the assumption that the media alone can make or break a celebrity. Her chief target in this regard is the fierce critique influentially advanced in Dialectic of Enlightenment of “the culture industry” as both profoundly anti-individualistic and all-pervasive.1 According to Marcus, the dominance of the Hollywood studio system at the time blinded Horkheimer and Adorno to a longer and more unsettled history, one in which individual celebrities and their various publics have had as much say in the outcome as the media.

In her account, the age of the Internet has returned us to the comparative anarchy that prevailed in the nineteenth century, before the power of the studios and then of broadcast television temporarily obscured the fundamental dynamics of celebrity. The “drama” of Marcus’s title plays on the double burden of her argument: at once a gesture to Bernhardt’s principal medium and an appreciation of the suspenseful struggle between competing forces that determines who will—or won’t—achieve stardom.

Horkheimer and Adorno complained that films imposed “an essential sameness on their characters…excluding any faces which do not conform,” but Marcus views Bernhardt’s career as representative of a history that extends beyond the studio era, one in which unconventional looks have not always proved a bar to celebrity. The illegitimate daughter of a Jewish courtesan, with a prominent nose, frizzy hair, and a lanky figure mocked for its thinness, Bernhardt succeeded in wooing the public by flaunting her idiosyncratic appearance rather than minimizing it. Onstage, she became famous for deliberately contorting her body into expressive gestures that exaggerated her sinuous form; offstage, she courted ridicule by posing in tight-fitting costumes or pantsuits, while encouraging rumors that she drank from a skull and kept a skeleton in her bedroom—thus doubling down on the boniness about which others never tired of joking.

Marcus aptly compares Bernhardt’s resistance to body shaming with Barbra Streisand’s and Lena Dunham’s, an analogy that loses none of its force from the obvious reversal in the standard of beauty the latter is defying. Marcus also contends that celebrity was less stigmatized in an era when female celebrities were still the exception, although in Bernhardt’s career she traces the beginnings of a process by which the typical celebrity—and her fans—were increasingly feminized. It’s no accident, she suggests, that when John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign sought to dismiss Barack Obama as a mere celebrity, the other examples it invoked were Britney Spears and Paris Hilton.

More fundamentally, Marcus takes the French actress as the prototype for a kind of celebrity who triumphs by upending social convention—a stance that in Bernhardt’s case included the shameless parading of her illegitimate son, named after herself rather than the father, her late marriage to Jacques Damala, ten years her junior, and her long-standing relationship with the painter Louise Abbéma, as well as more professionally consequent acts of defiance, such as breaking her contract with the Comédie-Française in 1880 in order to embark on her tours of Europe and North America, or her lifelong practice of managing her own troupes and supervising the staging of all her productions, including the leasing of theaters.

Here, too, Marcus invokes more recent analogues of Bernhardt’s maneuvers, like James Brown’s seizing creative and commercial control of his output after acquiring the master tapes of his best-selling 1963 record Live at the Apollo; but her larger aim is to redeem celebrity, at least partly, from the charge of deadening conformity leveled by intellectuals following the example of Horkheimer and Adorno. Pointedly quoting Lord Byron (“I almost think people like to be contradicted”) and Oscar Wilde (the public “likes to be annoyed”), she argues that celebrities serve to channel our resistant impulses as much as they model social norms. Marcus is fond of paradox, however, and like other claims advanced in The Drama of Celebrity, this entails a tricky balancing act. Even as she highlights such defiance, she is forced to acknowledge that it only works because we view the performer as an exception: an avatar of rebellion who indulges our antisocial fantasies without producing any “broad social effects.”

Advertisement

“The more singular a celebrity,” Marcus announces, “the easier they are to replicate.” This characteristic paradox is primarily directed against Walter Benjamin’s oft-cited essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935), in which he argued that contemporary media had destroyed the “aura” previously emanating from individual artworks. For Benjamin, film dissipated the unique presence of a stage actor very much as photographic copies did that of an original painting, but Marcus contends that the replication of a celebrity’s image only intensifies what she calls the “halo of the multiple.” She has in mind not just the proliferation of photographs—a form of publicity that Bernhardt, whose career coincided with the emergence of commercial photography, put to brilliant use—but a star’s own performance of multiple roles, as well as her capacity to inspire others, both professional and amateur, to emulate her. So Bernhardt spawned a host of Bernhardt imitators, who managed to replicate the looks and gestures of the very actress pronounced “inimitable.” Offstage, fans could try to copy her style by purchasing countless products that sought to capitalize on her fame, from scarves and gloves to hair dyes and face powder. Though this traffic in Bernhardt’s image comes very close to the commodification of “type” so deplored by Horkheimer and Adorno—“every tenor,” they observed, “now sounds like a Caruso record”—Marcus emphasizes instead how it redounds to the glory of the imitated.

As James’s allusion to the “insanity” aroused by Bernhardt’s appearance suggests, nineteenth-century commentators were already bemoaning the actress’s effect on her admirers even before her wildly successful American tour the following year sent the satirists into overdrive. Marcus devotes particular attention to an elaborate French cartoon of 1881 in which a conquering “Sarah” arouses havoc in the US, inciting Mormon wives to revolution and prompting Native Americans to descend on Washington and scalp the senators, who then proclaim her empress. In yet another scene, a black waiter in Chicago serves up sausages ground from white men to the conquering visitor.

Fears of mass contagion have clearly attended celebrity from the start. But Marcus is less concerned to demonstrate that fact than to argue that those fears are overblown: even ardent fans, by her account, have always been capable of exercising individual judgment. Her principal exhibit here is an archive of theatrical scrapbooks, in which nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century theatergoers not only cut and pasted images of their favorite stars but recorded their verdicts on particular actors and performances. The Cleveland-based compiler of one such scrapbook in 1898 dutifully noted every play seen, adding a rank of “good,” “fair,” “poor,” or “fine” after each entry. Others ventured more nuanced judgments, discriminating, for example, the “stately…but stage” Olivia in a performance of Twelfth Night from the “vivacious” Maria and the “graceful—sweet—refined” Viola, whose voice was “at times too high.” Some amateur critics wrote directly to the actors in question, as when a correspondent informed Edwin Booth that his appearance in Richard III “was not sufficiently stern and sombre…. You might also…have a larger hump on the back & a more infirm gait as you move on the stage.”

Over the course of the century, the habitual rowdiness of theatrical audiences increasingly gave way to respectful silence, but Marcus sensibly questions those who identify such pacification with passivity. Indeed, new protocols of silence and darkness may have encouraged audiences to concentrate more intently on the performance, without being distracted by fellow theatergoers. Though we tend to think that only the Internet has enabled everyone to weigh in as a critic, Marcus demonstrates that individual debates about merit were a part of celebrity culture from the first. It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that some of the evidence she uncovers is no more enlightening than the average Amazon rating or Rotten Tomatoes review. Of two Ohio sisters who kept a theatrical scrapbook between 1886 and 1898, Marcus observes, “They penciled in very few notes, making it all the more significant when they did write ‘Very Good’ above the program for one play or ‘Splendid’ on another.” As someone who kept similar notes on books read as a child, I can’t take these rare jottings that seriously. They look more to me like occasional spasms of diligence on the part of women who mostly found the whole business of such recordkeeping tedious.

There’s no question, however, that nineteenth-century stars openly invited contests of judgment, whether by pitting themselves against their predecessors, as when Bernhardt courted comparison with the greatest French actress of the previous generation, Rachel Félix, or by adopting roles already made famous by other living competitors, as Bernhardt did with the Polish-born Helena Modjeska and the Italian Adelaide Ristori. Marcus, who calls the latter kind of competition “shadow repertory,” particularly notes Bernhardt’s contest with Modjeska over the role of Marguerite Gautier in La Dame aux camélias, the play adapted from the novel of the same name by Alexandre Dumas fils in 1852 (and probably most familiar to modern audiences from Verdi’s opera of the following year, La Traviata). A playbill of 1878 had acclaimed Modjeska “The Only Camille,” but over the following decade the part seems to have become definitively associated with Bernhardt—an association doubtless encouraged by the public’s knowledge of her own origins in a demimonde not unlike that of Dumas’s courtesan. So much was Bernhardt identified with the role that when other actresses chose to challenge her for supremacy, they repeatedly did so by tackling Camille.

Marcus argues that the relatively stable international repertory of the nineteenth-century theater lent itself to such contests, a point amply demonstrated by Peter Rader’s Playing to the Gods: Sarah Bernhardt, Eleonora Duse, and the Rivalry That Changed Acting Forever. Opening with Duse’s 1894 London appearance as Camille, which Bernhardt crossed the Channel to see, Rader structures his dual biography around the decades-long competition between the two actresses and their radically different approaches to their art. Neither woman has exactly suffered from biographical neglect—Rader is not even the first to combine their stories2—and his book, which originated as a screenplay, is casually sourced and prone to ascribing thoughts to historical persons without explanation. He also devotes much attention to his subjects’ love lives, especially Duse’s agonized affair with the Symbolist poet, dramatist, and novelist Gabriele d’Annunzio—a flagrant womanizer who managed to betray her artistically as well as sexually when he broke their compact to work only with each other and arranged for Bernhardt to debut in a play ostensibly composed for Duse.

Reveling in such anecdotes and breathlessly cross-cutting between narratives, Playing to the Gods nonetheless succeeds in demonstrating that the two women were essentially competing on different terms. While Bernhardt obviously won the celebrity contest—even today her name still resonates with people who know very little else about theater history—it’s the Italian Duse, fourteen years her junior (1858–1924), whose influence on their art has proved more lasting.

Born into a family of itinerant troubadours, Duse had been appearing on stage since she was four, but her contributions to the theater apparently owed little to formal training. A subtle actress known for her naturalistic style, she was a particularly gifted interpreter of Ibsen, whom she introduced to Italian audiences with a pioneering performance of A Doll’s House in 1891. (This was one arena in which Bernhardt wisely learned not to compete: prone to the sort of mannerisms the playwright deplored, she was fundamentally unsuited to conveying the nuanced psychology implied between his lines, and after one performance of The Lady from the Sea in Geneva in 1906, she never attempted Ibsen again.)

Unlike her French rival, whose flamboyant gestures, both onstage and off, continually reminded audiences of her presence, Duse preferred to disappear into her roles. For Anton Chekhov, who recoiled from the “ultra sensational” Bernhardt when she toured Russia in 1881, Duse’s visit a decade later was a revelation: “What a marvelous actress! Never before have I seen anything like it.” Another of her Russian admirers was Konstantin Stanislavski, whose famous acting system, partly inspired by Duse’s performances, would in turn shape generations of theater professionals, from Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler to Marlon Brando and Meryl Streep.

George Bernard Shaw had the chance to deliver his own verdict on the two rivals when he saw them in competing London productions of La Dame aux camélias and Hermann Sudermann’s Heimat in 1895. “It is always Sarah Bernhardt in her own capacity who does this to you,” he wrote of her performance as Sudermann’s heroine: “The dress, the title of the play, the order of the words may vary; but the woman is always the same. She does not enter into the leading character: she substitutes herself for it. All this is precisely what does not happen in the case of Duse, whose every part is a separate creation.”

For Marcus, judging merit is an intrinsic part of celebrity culture, and Shaw was merely hoping “to anoint a newer and worthier star,” but I think he was drawing a more fundamental distinction: Duse was the greater actress “precisely” because she did not act as a celebrity. “Even in a country like America, where, I am told, exaggerated advertising is absolutely necessary,” as she had written to the managers of her first US tour, Duse approached her career in a spirit very different from her predecessor’s. When a reporter managed to corner her in a New York elevator, she coolly informed him, “On Monday night I shall appear in public, and I will be seen upon the stage. Away from that I do not exist.” From the standpoint of celebrity culture, at least, this was a fatal mistake. As her rival tartly observed of Duse’s disappearing acts, “No personality emerges from her art that can be identified with her name.”

The Drama of Celebrity is premised on a fundamental continuity between Bernhardt’s era and our own, and Marcus is surely right to contend that the star did much to invent what we now recognize as celebrity culture. A canny exploiter of modern technology, she was quick to adapt her theatrical gifts to other media, making her first phonograph recording with a few lines from Phèdre on a visit to Thomas Edison in 1880 and her first film crossing swords with Laertes in the duel scene from Hamlet at the Paris Expo two decades later. Though Marcus doesn’t mention it, Bernhardt once even toyed with launching a political campaign to boost her celebrity. According to Rader, she announced in 1892 that she intended to leave the theater and run for a seat in France’s Chamber of Deputies, where she would champion “special legislation for women”—a gesture that was widely regarded as a publicity stunt. Unlike more recent instances of the phenomenon, however, this particular attempt at celebrity politics appears to have fizzled out quickly.

But while it may be true, as Marcus suggests, that Bernhardt anticipated virtually every move in the modern celebrity playbook, there’s also something potentially misleading about the decision to treat her career as representative. The technological developments at the center of Douglas and McDonnell’s book mostly postdate the actress’s death, and it’s hard not to feel that they have made more of a difference than Marcus allows. Douglas and McDonnell’s observation that “radio revolutionized fandom and celebrity because now, for the first time, a mass medium penetrated directly into your home, bringing the stars into your domestic space,” highlights a transformation that has only intensified in the era of twenty-four-hour cable and Twitter—not to mention the omnipresent earbud, carrying the voice of an otherwise distant person directly into your head. Celebrity has always depended on an illusion of intimacy with the public, but we are a long way from the theater fans who were mostly content, in Marcus’s phrase, “to limit their desires for proximity to their favorite stars to words and images.”

Marcus began her book, by her own account, in the midst of Obama’s first campaign for the presidency, and she has bravely persisted in her partial defense of celebrity culture even in the face of a political version she clearly finds appalling. Yet by underestimating how the rapid expansion of mass media in the century since Bernhardt’s death has heightened the illusion of intimacy, she also risks minimizing how politicians in this country and elsewhere have managed to manipulate it. Douglas and McConnell remark that obsessing over celebrities can serve as a welcome distraction for those whose feelings of impotence have only intensified in an age of structural inequality. The constant reality show in the White House is another such distraction, of course. But by persuading the audience that its star speaks right to them, it also offers a more immediate antidote to his supporters’ feelings of powerlessness. Imagining that you have a direct connection to the most important man on the planet may not do anything for your family’s health or your bank balance, but it can make you feel as if anything is possible.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly named the play in which the character Olivia appears. It is Twelfth Night, not As You Like It. The text above has been amended.

This Issue

September 26, 2019

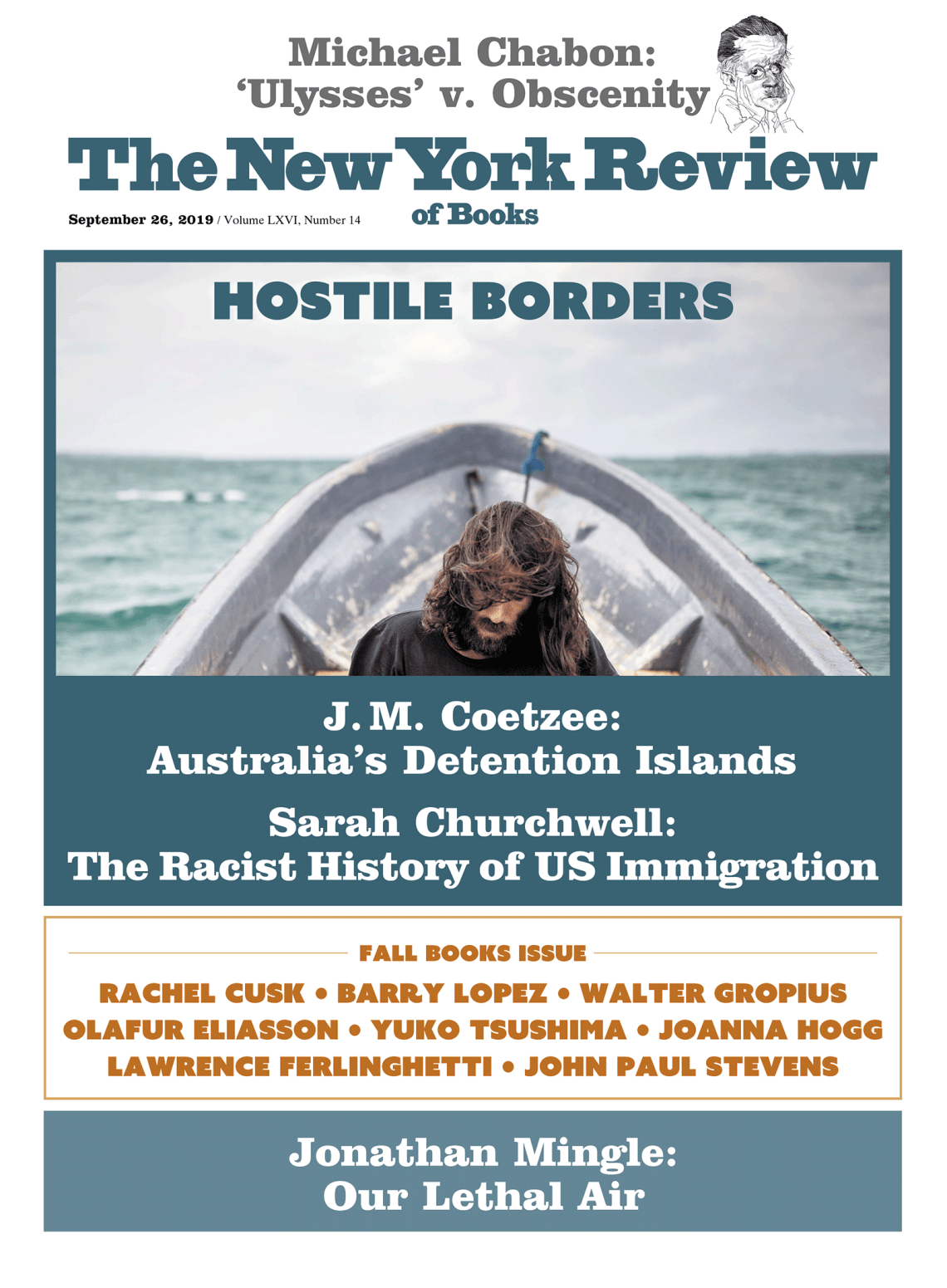

Australia’s Shame

Brexit: Fools Rush Out

‘Ulysses’ on Trial

-

1

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr and translated by Edmund Jephcott (Stanford University Press, 2002), pp. 94–136. ↩

-

2

See Henry W. Knepler, The Gilded Stage: The Lives and Careers of Four Great Actresses: Rachel Félix, Adelaide Ristori, Sarah Bernhardt and Eleonora Duse (Constable, 1968); and John Stokes, Michael R. Booth, and Susan Bassnett, Bernhardt, Terry, Duse: The Actress in Her Time (Cambridge University Press, 1988). ↩