Andrew J. Torget begins his 2015 book Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800–1850 with the story of five people whose journey into what was then “northern New Spain” effectively captures the origins of what would become the largest of the contiguous states of the American Union. In 1819 “Marian, Richard, and Tivi” escaped from slavery on a plantation in Louisiana, hoping to find freedom in Spanish territory. The following year, James Kirkham, the man who claimed ownership of them, went looking for the escapees, and on his way encountered another Anglo-American, Moses Austin. Austin, a Connecticut-born Missouri transplant, would gain a place in history for getting the first land grant “from Spanish authorities to begin settling American families in Texas”—the name the Spanish had given the region that they had fought to take from the Comanches for over a century. Austin’s task was not just to convince whites to move to Texas. He also had to encourage “the Spanish government…to endorse the enslavement of men and women like Marian, Richard, and Tivi, since American farmers would not abandon the United States if they also had to abandon the labor system that made their cotton fields so profitable.” Austin died in 1821, before his project could begin in earnest, but his son Stephen F. Austin would take up his dreams of colonization and become famous as a founding father of the Lone Star State.

So “three driving forces—cotton, slavery, and empire” had brought the enslaved, an enslaver, and a colonizer into Texas, to coexist (or not) with the Native Americans and Mexicans who were already there. Their convergence in this place, and their differing and clashing interests, reveal what early Texas was truly about. It explains why the state, even before it was a state, was seen as a problem—or an opportunity, depending on one’s view of the expansion of slavery—from the moment it became clear that its future might lie within the United States of America. The whites who had come to Texas before Austin’s venture—most with enslaved people in tow—expected to create farms and plantations to grow cotton, and they were convinced this could not be done without enslaved labor. According to Torget, Austin argued forcefully to legislators that “opening northeastern Mexico to American colonization depended on ensuring that slavery remain legal in Texas.”

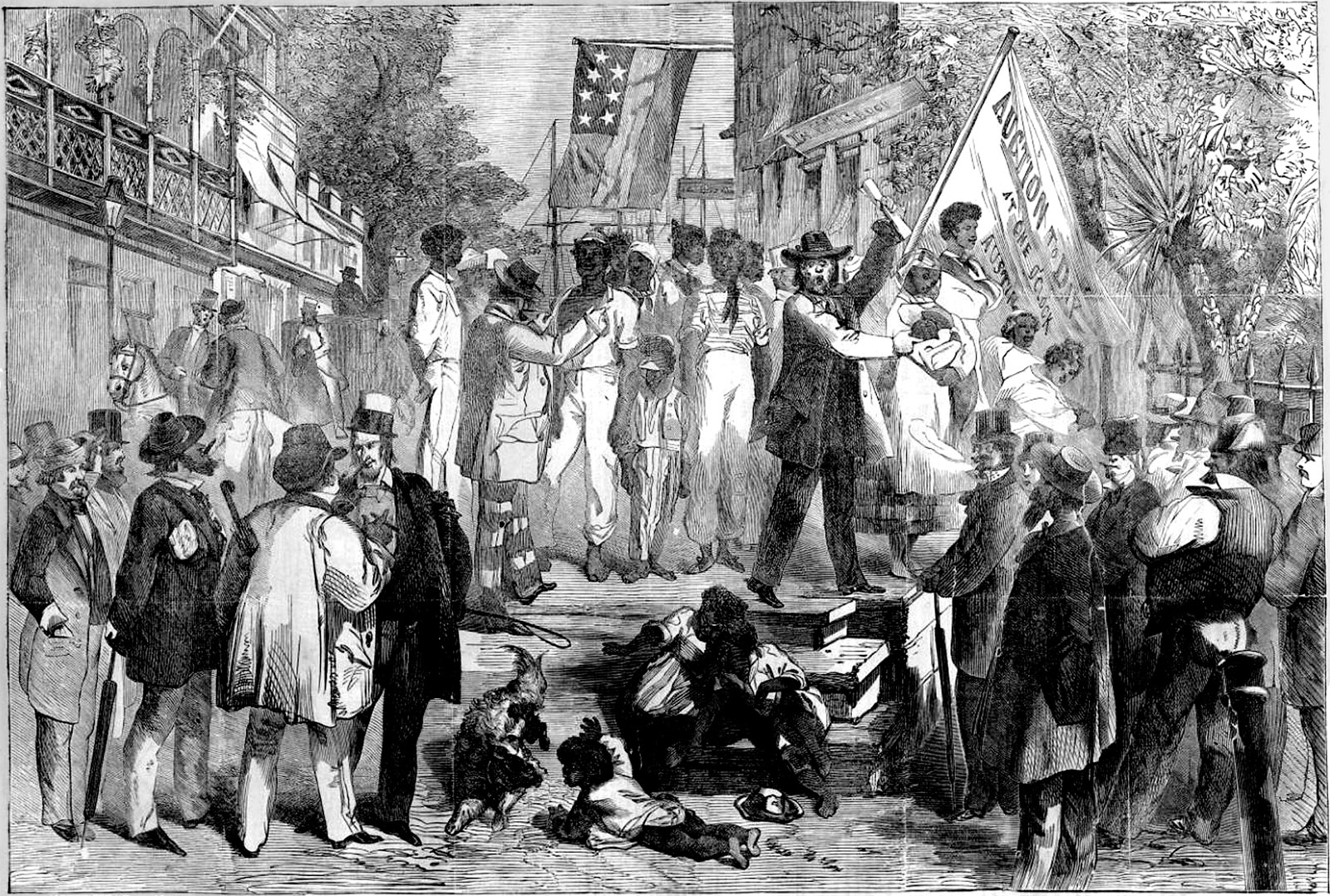

The Mexican government abolished slavery in 1829 but turned a blind eye to the institution in Texas. Eventually, as their numbers grew, the anxious Anglo settlers wanted firmer assurances of their rights as slaveholders, and sought independence. The short-lived Republic of Texas they created in 1836 provided as much protection for slavery as possible. Texas’s 1845 annexation by the United States was controversial in some parts of the country precisely because everyone knew the Republic had been constituted as a slaveholder’s republic and was full of people who were enthusiastic about chattel slavery. Bringing Texas into the Union would upset the balance of power between the Northern free states and Southern slave states.

It’s very likely that when most people in the United States—and in the world—think about Texas, they do not think of the foundational forces described above. Thanks to Hollywood, the conflict with the Comanches—which continued for decades after New Spain became Mexico, and after the Republic of Texas became the State of Texas—may come to mind. Certainly, cowboys and cattle ranchers in possession of vast acres have taken their place as figures emblematic of the state. And then, of course, there is oil. Spindletop, the phenomenal 1901 gusher that produced more than 100,000 barrels of oil over a nine-day period, and other spectacular strikes at the Sour Lake, Humble, and Batson-Old fields, made Texas the world’s leading producer of oil for years. This created another stereotype to go along with the cowboy and the prosperous cattle rancher: the vulgar nouveau riche Texas millionaire prone to bragging about being in “the oil bidness.”

Giant, the classic movie based on Edna Ferber’s novel of the same name, brought the cattle ranch and the oil field together, burning those images of Texas into the minds of millions. All of the books under review mention the film. It presents the cattle rancher, and those affiliated with cattle operations, as the original, authentic Texans, who had their way of life disrupted by an oil boom that transformed everyone’s relationship to the land. Although the movie ends on a hopeful note, a sense of loss runs through it. Larry McMurtry’s depiction of Texas, in his collection of essays In a Narrow Grave—recently reissued for its fiftieth anniversary—has much in common with the film. Nostalgia for a lost Texas—a Texas based on the ways of cattle ranching—permeates both. And both proceed as if the state’s history with slave-based agriculture did not exist, or should have no real bearing on the way the state is perceived.

Advertisement

McMurtry was raised in a family steeped in the West Texas lore of the cowboy and the range. The book’s final essay, “Take My Saddle from the Wall: A Valediction,” makes the point plainly:

I realize that in closing with the McMurtrys I may only succeed in twisting a final, awkward knot into this uneven braid, for they bespeak the region—indeed, are eloquent of it—and I am quite as often split in my feelings about them as I am in my feelings about Texas. They pertain, of course, both to the Old Texas and the New, but I choose them here particularly because of another pertinence. All of them gave such religious allegiance as they had to give to that god I mentioned in my introduction: the god whose principal myth was the myth of the Cowboy, the ground of whose divinity was the Range.

McMurtry is also an acclaimed screenwriter, and has himself contributed to the Hollywood version of Texas. His first novel, Horseman, Pass By (1961), was made into the movie Hud. That and his other novels that were turned into movies or television shows—The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment, Lonesome Dove—deal with the cowboy mentality, figuratively if not literally. He understands Hollywood well, and one of the book’s essays, “Cowboys, Movies, Myths, and Cadillacs,” shows he knows just how much Hollywood has shaped the image of Texas. But it is not clear that he understands the extent to which that image, situating the state in “the West” and not “the South,” buries huge, defining swaths of Texas history and culture, along with the experiences of people who were and are, in fact, Texans.

There is ample reason to think of Texas as separate from the South, and to think of it as separate from the West, too. The Balcones Fault roughly bisects the state, creating a division between East and West. The vast majority of the population has always lived in the eastern part of Texas, a fact McMurtry acknowledges. That the less populous region of the state would come to define it is ironic and curious.

We all have family stories. Mine is of an enslaved great-great-grandmother brought to East Texas from Mississippi in the 1850s, before McMurtry’s family arrived in West Texas. Freed by her father as a child, along with her mother, she grew up to marry and raise a family, including my great-grandmother, who, with her husband, owned a cotton farm in East Texas. And then there was my father’s great-grandfather: he came out of slavery, and saved to buy a few hundred acres of land with his brothers. They became lumberjacks, cutting and selling timber to make a living. Cotton and timber: both have been integral to the economy and culture of Texas for most of the state’s history.

McMurtry does write of East Texas, saying that his family had always looked down on the people there because they were farmers. He also declares that area of his home state part of the South, and not really Texan. He invokes William Faulkner, whose writings show his grasp of the weight of history and his willingness to grapple with it:

It has clearly become necessary to write discursively of Texas if one is to be heard at all beyond one’s city limits. The South, fortunately for its writers, has always been dark and bloody ground, but Texas is only scenery, and poor scenery at that.

Well, the ground of Texas is pretty “dark and bloody” too, for the same reasons it was so in Faulkner’s Mississippi and for reasons unique to Texas. One of McMurtry’s own essays, “Southwestern Literature?,” describes in great detail the depredations of the Texas Rangers, who, after their beginnings in 1823, developed a reputation as expert killers of nonwhites. What would Texas literature look like if more of its writers had, over the years, mined this rich but tragic terrain instead of focusing on the blinkered mythology of the cowboy—a mythology that excluded the large numbers of cowboys who were black? In saying that his white and male family members “bespeak the region,” McMurtry, as have others before and since, pronounces Texas a white man. Many—certainly not all—people who read these essays fifty years ago would have seen no problem with such a pronouncement. It is likely that more would object today. The world has, indeed, changed.

Lawrence Wright, a staff writer at The New Yorker and a screenwriter, was born in Oklahoma but has spent most of his life in Texas. He says that he has “come to appreciate what the state symbolizes, both to people who live here and to those who view it from afar.” God Save Texas: A Journey into the Soul of the Lone Star State, also a book of essays, is another attempt to get at the meaning of a place that has been contentious from the very beginning of its time in the Union. While it would be wrong to place too much emphasis on determinism and birthplace, Wright appears more detached from Texas than McMurtry, whose familial roots go deeper. There is no sense of loss in Wright’s prose, no yearning for a supposedly disappearing Texas past, no presentation of a singular mentality that defines the state. Instead, there is a clear-eyed journalist’s view of the people encountered and the places visited. The predominant impression the reader takes away from the book is one of alarm. Wright fears that the rest of the country may come to resemble Texas in ways that will not do the nation much good:

Advertisement

I think Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation. Because Texas is a part of almost everything in modern America—the South, the West, the Plains, Hispanic and immigrant communities, the border, the divide between the rural areas and the cities—what happens here tends to disproportionately affect the rest of the nation. Illinois and New Jersey may be more corrupt, Kansas and Louisiana more dysfunctional, but they don’t bear the responsibility of being the future.

A past may lead to a future, and Wright understands the importance of the entirety of Texas’s history, as well as the importance of all its regions, in shaping what it has become. He recognizes the hold that the myth of the cowboy has had, along with the “danger in holding on to a myth.” It can become, he says, “like a religion we’ve stopped believing in. It no longer instructs us; it only stultifies us.” Moving beyond myth, Wright’s explanation of the culture of Texans explicitly invokes the state’s history and the diversity of its people:

From my lifelong field studies spent among Texans, I have formulated a theory of cultural development….

Level One is aggressive, innovative, and self-assured. It erupts from the instinctive human reaction to circumstance. The paisano presses his tortilla, the slave mixes his corn bread, the cattleman rubs prairie sage on the roasting steer, and a cuisine is irrepressibly born from the converging streams of traditions and available flavors. Spanish priests mortar limestone rocks with river mud; bankrupt Georgia farmers, remembering the verandas of their plantation empire and mindful of the withering sun, build high-ceilinged houses with broad, shaded porches; thus a native architecture arises. In scores of county seats laid out in the 1880s, the Virginian idea of the central courthouse square meets the Spanish idea of the town plaza and the Victorian idea of wedding-cake masonry, creating an idiom of civic democracy…. All of our culture overlays this primitive template, just as the Houston freeways inscribe the same routes once traced by ox wagons headed for Market Square.

Recalling in this way the racial and cultural palimpsest that forms the real substance of Texas, one realizes how much effort it has always taken to suppress the truth that Texas is not, in essence, a white man.

What, then, is Texas? Should we even think about so large and diverse a place as having an essence that can be distilled? The document of annexation to the United States provided that Texas could be divided into five separate states, a likely moribund provision that present-day Texans (sometimes jokingly, sometimes not) still invoke. The landscape runs from the lush forests of the east to the desert of the west. The part of Mexico that became Texas has been diverse from its earliest days, and not in a harmonious way. It is the only state to have its own electrical grid. And if Wright fears that Texas’s “immature political culture” has too greatly influenced the nation’s political culture, it is worth noting that the Beto O’Rourke phenomenon—at least as far as the Senate race went—suggests that things may be changing in the state. Texas has been “red” because of voter suppression coupled with insufficient voter participation. If the structural barriers to voting are removed, and if more Texans decide to vote, the state could soon be sending a very different message to the nation about what the future should look like.

Monica Muñoz Martinez’s The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas approaches Texas by focusing intently on the state’s “dark and bloody ground,” looking at the years between 1910 and 1920, when white vigilantes, the Texas Rangers, and other law enforcement entities engaged in a wave of anti-Mexican violence. The book uses documentary evidence and the oral histories of families whose members were victimized during this period:

Searching the Texas landscape for the remains of a loved one was an awful—and awfully familiar—ritual, repeated countless times before. By 1918, the murder of ethnic Mexicans had become commonplace on the Texas–Mexico border, a violence systematically justified by vigilantes and state authorities alike. Historians estimate that between 1848 and 1928 in Texas alone, 232 ethnic Mexicans were lynched by vigilante groups of three or more people. These tabulations only tell part of the story.

One of Martinez’s most important contributions is to remind us that violence against nonwhites was not simply a matter of private citizens going out of control for private reasons. “Vigilante violence on the border had a state-building function,” she writes. “It both directed the public to act with force to sustain hierarchies of race and class and complemented the brutal methods of law enforcement in this period.”

What kind of state was to be built? Martinez’s primary subject is the way all of this played out on the Texas–Mexico border between white Texans and ethnic Mexicans. It is a story that should be more widely known, and Martinez tells it with great passion and precision. But, importantly, she links the experiences of Mexican-Americans to those of African-Americans, understanding that enforcing white racial supremacy, through violence and other means—disfranchisement and Jim Crow—goes to the very heart of the story of Texas:

Although histories of anti-black and anti-Mexican violence have been segregated in popular memories of this period, the ideologies that condoned violence in Texas against those communities mutually informed and justified one another. To fully comprehend the culture of impunity that allowed anti-Mexican violence to thrive in Texas, it is necessary to consider the ongoing history of anti-black violence in the state.

The state-building was being done on behalf of whites, which was perfectly in keeping with the intentions of the people who embarked on the idea of Anglo-American settlement during the early part of the nineteenth century.

This brings us back to the founders of Texas. Stephen F. Austin, who like a number of his generation said that he viewed slavery as a necessary evil, for a brief time changed his mind about the institution. Morality played no part in this shift. He looked with alarm at the growing population of blacks in other Deep South states, and feared that one day blacks in Texas would engulf whites. Austin’s fear was rooted in the nightmare scenario of black men rising up to kill whites and have sex with white women. He wrote, “Suppose that you will be alive at the period above mentioned”—when blacks reached parity with or outnumbered whites—“that you have a long-cherished and beloved wife, a number of daughters, grand daughters, and great-grand daughters.” This was, in his mind, a contest for racial supremacy. After the Confederate defeat in the Civil War, when white Texans lost the legal control over black Texans that the laws of slavery had provided, the “border” was wherever blacks and whites were in the state. The stories of violence and loss that the families in The Injustice Never Leaves You worked so valiantly to keep alive could be told in nonwhite communities throughout Texas. All of this is far away from lonesome cowboys on the range, living out a life of rugged individualism and fierce independence. Martinez’s book suggests why many white Texans prefer that the world accept the myth over the reality.

Like the state of which he writes, Stephen Harrigan’s book on Texas is big; the word is in the title: Big Wonderful Thing: A History of Texas. Harrigan, an award-winning historical novelist and Texas Monthly contributor, starts with the story of the native peoples who fashioned “Alibates flint into the distinctively styled spear and projectile points that are classified today as Clovis.” He moves onto the Karankawas, who in 1528 became the first native group in Texas to encounter the Spanish, beginning an engagement with Europeans (the French would soon follow the Spanish) that would transform the lives of all native peoples in the area. Then there were other groups—among them the Caddo, the Apaches, and the most obstreperous (from the European perspective), the Comanches:

“Their name is Comanche.” It’s a simple enough statement, but one that, when considered against the next few hundred years of Texas history, takes on an ominous oracular force. Long before the Comanches began to clash with Spanish in Texas, they were well known to the soldiers and settlers and priests of New Mexico, and to the Pueblo Indians there, who were restively under Spanish control.

The horses the Spanish brought to the area made their way into the lives of native peoples, affecting no one more than the Comanches. “Horses,” Harrigan writes, “became their culture.” The horse culture, combined with their effective battle strategy, helped the Comanches build an empire that, for decades, challenged Spanish encroachment. Harrigan’s account confirms that the drama of this protracted engagement helped give rise to the “cowboys and Indians” trope that has so defined Texas and the West. We know how that contest ended, and Harrigan quotes the poignant statement of a Comanche chief, Ten Bears, who said he had been

born under the praire, where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun…. I know every stream and wood between the Rio Grande and the Arkansas. I have hunted and lived over that country. I live like my fathers before me and like them I lived happily…. If the Texans had kept out of my country, there might have been peace.

But “the Texans,” by which he meant people of European descent, would not stay out. The lure of land and prosperity was too strong for that. Harrigan understands the centrality of East Texas to this story, and to the development of the basic character of the state. There were those who wanted to capture the land all the way to the Rio Grande, largely to prevent Spain from maintaining control of the area. But others fixated on “East Texas, the fertile crescent of arable deep-soiled land, rich river bottoms, and coastal prairies extending roughly from San Antonio de Béxar to Nacogdoches, from the Colorado River to the Sabine.” This is largely the area in which the cotton and sugar-based plantation economy took hold:

The fact that Spain had neglected this paradise, had failed to people it and protect it, to cultivate it and mine it, was an affront almost against nature itself. And the fact that the United States was already locked in a struggle over the expansion of slavery, with eleven free states tipping the balance against ten slave states…, meant that Texas offered a potentially ripe opportunity to extend the dominion of human bondage.

Harrigan reinforces the idea that most people do not think of Texas in relationship to slavery. The state’s “western half—its cowboy half, its plains-and-desert half—acts as a kind of psychic counterweight to the cotton-kingdom identity that links it with the Old South.” But linked it was. It was no surprise that Texas joined the Confederacy in the hope of maintaining slavery and control over African-Americans. As things turned out, Anglo-Texans did not have long to develop their slave-based economy. The Civil War broke out fifteen years after Texas became a part of the country. Like all Southern states, it resisted Reconstruction and unleashed violence against the people it had formerly held in bondage. Quoting from letters, Harrigan reveals the depth of the hatred that many white Texans felt for all the nonwhites in their midst. They were firm in their belief that the state had been established for white people who were to have dominion over nonwhites. Harrigan echoes McMurtry and Martinez on the violence perpetrated against Mexican-Americans. There were exceptions, but the book leaves no doubt about the origins of the state’s troubled racial history.

The great strength of Harrigan’s work is that he tells the stories of all the types of people who have lived in Texas, from its earliest days into modern times, with a sense that all of their lives mattered in fashioning the state’s identity. Barbara Jordan, the congresswoman from Houston, was a Texan. Jessie Daniel Ames, a white woman who campaigned against lynching, was a Texan. Emma Tenayuca, the labor agitator, was a Texan, as were Sam Houston and Lyndon Baines Johnson. Texas is a large place with no one defining character, save for many residents’ confident belief that to be a Texan is to be special.

What does all this add up to? How has Texas’s place in the American Union made a difference? How has the history of Texas directed the progress of the state and of the nation? Lawrence Wright’s assertion that Texas has exerted a powerful influence, and will continue to do so, on the American political landscape finds additional support in Lucas A. Powe Jr.’s America’s Lone Star Constitution: How Supreme Court Cases from Texas Shape the Nation. Cases originating in Texas have determined, among other things, the way many Americans vote, their right to choose to have an abortion, the way public schools can be funded, and the right for people of the same sex to engage in sexual activity together.

The history, diversity, and geography of Texas all explain what Powe identifies as the state’s disproportionate effect on American constitutional law, and thus on the entirety of the United States:

More important United States Supreme Court cases have originated in Texas than in any other state, so many, in fact, that entire basic courses in Constitutional Law in both law schools and political science departments could be taught using nothing but Texas cases.

Powe’s accessible and well-researched account demonstrates why “Texas and not California…provides breadth and depth to constitutional adjudication” that has had the deepest impact on the nation’s laws. The state’s Southern character has also made it a source of resistance to racial discrimination. The focus on its western character, which grows out of that region’s wide-open spaces, was, Powe argues, an early-twentieth-century adaptation designed to erase its connection to the South: “The Civil War and the ‘Lost Cause’ were downplayed.” Texas is vast, with a mineral resource, oil, that has shaped its place nationally and internationally. Powe reminds us that “until displaced by OPEC in the early 1970s, the Texas Railroad Commission set the world price of oil.” Cases about energy produced in Texas were closely watched during the New Deal as the state resisted various federal regulations.

Powe references the early struggle over the inclusion of Texas into the Union, with John Quincy Adams’s pronouncement that “the annexation of an independent foreign power [Texas] would be ipso facto a dissolution of this Union.” The sense of the foreignness of Texas, and its own pride at having once been independent, created a combative posture toward the national government from the very start. Texas was a Republic. That is why the constitutional law originating in Texas is so rich and pervasive. Like Wright, Powe is discomfited by the state’s outsized influence on national law. It is unlikely, however, that this influence will wane anytime soon.

In addition to being a state, Texas is also, Powe says, “a state of mind.” If one knew nothing about it at all and read these five books, it is likely that one would not come away with a favorable impression. And yet there is something about the place—and its state of mind—that appeals. It is one of the fastest-growing states in the country. People go there seeking fortunes of one kind or another, hoping to find a place for themselves somewhere between what is real and what is myth. It is my home state, and I never feel freer than when driving along a Texas highway, on my way to a somewhere of endless possibilities. I know the problems that others who traveled on those roads have experienced throughout history—and continue to experience. To a degree, that history and its legacy led me to trade one place within a strong mythology for the only other place in the country with as big a sense of itself as Texas: New York City. But the notion of a special freedom in Texas—a hope, actually—is reflexive for me. It is strange and disturbing to think that this hope may in any way resemble the feeling that brought thousands of Anglo settlers, along with the people they enslaved, into the region so long ago.

This Issue

October 24, 2019

In Defense of Fiction

Snowden in the Labyrinth