The second wave of the American feminist movement produced a lot of books. The Feminine Mystique, Sexual Politics, The Dialectic of Sex—best seller followed best seller, each looking at how some combination of custom, law, and centuries-old ideologies led to the gendered divisions of labor and status that obtained in the US in the Sixties and Seventies: women concentrated in low-paying jobs or unpaid volunteer work, responsible for housework and childcare, largely absent from government and the upper and middle ranks of most industries and professions, making photocopies and coffee for radical men who made speeches.

Every ten years or so, publishers reissue these books with new introductions, and critics recommend them. But just try reading one. Some of their central insights have so thoroughly entered the mainstream of culture that they now seem obvious, while other claims have been qualified and corrected by successive generations. Either way, they seem trapped in their time. “After a few chapters I began to find much of it boring and dated,” writes historian Stephanie Coontz of reading The Feminine Mystique (which had been very important to her mother) for the first time as an adult. “It made claims about women’s history that I knew were oversimplified,” she continues, and Betty Friedan’s “generalizations about women seemed so limited by her white middle-class experience that I thought the book’s prescriptions for improving women’s lives were irrelevant to working class and African-American women.” Coontz writes this in A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s, in which she ends up complicating some of her own negative first impressions of The Feminine Mystique. Which suggests you may need to read (or write) a second book, one of historical exegesis, to appreciate a feminist classic.

During an interview a few years ago, I asked the essayist and memoirist Vivian Gornick, who had been active in the movement, what she thought of those books today. “Oh, they’re unreadable now,” she shrugged, no trace of lament. “It’s like that with a lot of firebrand writing, you know. It’s hardly ever literature.” Yet, as Gornick has written, millions of people read the books, saw truth in them, and were moved to action: they marched or they made changes in their own lives or both, and collectively these actions moved their society closer to its egalitarian principles. Literature or not, the second-wave classics played their part in a kind of ideal meeting of reader and book.

The writer who invented the genre was neither a feminist nor an American. Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex was published in France in 1949 when she was forty-one years old. A few years later, its English translation would haunt and inspire Friedan, Kate Millett, and Shulamith Firestone. When she wrote it, Beauvoir, a socialist, did not see the need for a political movement specifically for women’s rights. It was a time of feminist quiescence, when activism on behalf of women seemed to belong to the past rather than the future. Earlier in the century, there had been an expansion of education opportunities for women in France: they had won the right to sit for the prestigious French agrégation exam that was the entry point to university teaching. Beauvoir had been the ninth woman to pass the exam in philosophy, and more women entered the field behind her. As of 1944, women also had the right to vote. They were on their way. But something nagged at the philosopher. “The situation of woman,” she writes in her introduction, “is that she—a free and autonomous being like all human creatures—nevertheless finds herself living in a world where men compel her to assume the status of the Other.”

Beauvoir was drawing on the longstanding philosophical concept of the Other, especially as developed by Hegel and Husserl and, most recently, her partner, Jean-Paul Sartre: the Other is a consciousness outside the self whose vexing discovery is crucial to our formation of a full sense of selfhood. A lot can go wrong in the encounter. Beauvoir’s first novel, L’Invitée (1943), explored the problem of the existence of other people in the context of a love triangle culminating in murder, while Sartre, in Being and Nothingness (1943) and his play No Exit (1944), highlighted the peculiar shame of falling under another person’s gaze, helplessly subject to his interpretations.

In The Second Sex, Beauvoir turns to this problem as it plays out among social groups. Any two people from different backgrounds might seem foreign to each other, she writes in her introduction, but ordinarily each understands that to the other he is the foreigner. “Foreignness” or “difference” is—or should be—a reciprocal concept. But there can be groups of people, Beauvoir continues, whose foreignness becomes fixed in their society. She points to Jews in Europe and blacks in the United States as well-known examples of minorities who are perennially excluded from their respective societies’ self-definition. The dominant majority has widespread social permission to doubt and deny the selfhood of the minority, and over generations this doubt can creep into the consciousness of the minority members themselves: they become permanent Others. Women, Beauvoir argues, are another kind of Other. Though she’s not a minority anywhere, woman in Western society has been widely imagined as a deviation from the male standard—and not a deviation for the better. Women’s reciprocal claims to selfhood are commonly doubted and denied.

Advertisement

A strange kind of doggedly researched, densely argued work of nonfiction arranged itself around this observation. Beauvoir shows in The Second Sex how centuries of law, custom, and myth have reiterated the idea that female people are not quite as good, or as real, or as human as male ones. Patriarchalism has a history, she reveals, and a set of self-serving blind spots observable in all manner of Western thought (biology, philosophy, psychoanalysis, literature—she reviews them all). Most grippingly, Beauvoir spends about five hundred pages illustrating, in novelistic detail, how male-dominant culture can come to bear on women’s inner lives, impressing them so early and profoundly in their development that they can seem less good and less real even to themselves. Beginning with the Existentialist principle that every human consciousness seeks to project itself outward and act upon the world, Beauvoir argues that the human consciousness housed in a female body in twentieth-century France is, in certain consistent ways, checked from early childhood in its attempts to project and to act, and is instead pressed to identify with perspectives other than its own—to perceive itself from the outside.

Beauvoir’s notion is akin to W.E.B. Du Bois’s racial double consciousness, the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” that he had described forty-five years earlier in The Souls of Black Folk. Beauvoir’s was the first attempt to show how consciousness of one’s lower status, of one’s deviance from the norm, can affect women. Though earlier thinkers like Mary Wollstonecraft, John Stuart Mill, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had made the case for women’s rights, Beauvoir went beyond advocacy: her deep study of the philosophy, psychology, and history of female alterity opened up entirely new channels of thought. With The Second Sex, the modern feminist polemic was born.

Beauvoir grew up in a bourgeois Parisian family, attended a convent school, and nursed an outlandish desire to study philosophy. Her ambition was spurred by a magazine picture of Léontine Zanta, the first woman in France to have received a doctorate in philosophy, photographed “in a grave and thoughtful posture, sitting at her desk,” as she recalled in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1954). Beauvoir was a brilliant student but not a success in her parents’ straitened Parisian social world (“I found smiling difficult”), and she had no inheritance. Her parents reluctantly accepted her ambitions. The most prestigious path, the École Normale Supérieure, was closed to women at that time, so Beauvoir began by studying math and literature at two other colleges as she prepared for entrance examinations to the Sorbonne, where she finally went on to study philosophy.

She joined a study group with Paul Nizan, the future novelist; René Maheu, a future director-general of UNESCO; and an aspiring philosopher, brilliant by reputation, named Jean-Paul Sartre. Maheu invited Beauvoir to Sartre’s rooms one evening to help them study Leibniz (she wrote a dissertation on him). The meeting has entered legend as the beginning of Beauvoir and Sartre’s fifty-plus-year partnership, a relationship that still seems notably modern yet was arranged sensibly, with seemingly little rebellious energy. Sartre had once been engaged and was now determined never to marry. Beauvoir also had her doubts about marriage (marriage “doubles one’s domestic responsibilities”). About three months after they met, Beauvoir and Sartre made a pact about the future course of their partnership beside a fountain in the Luxembourg Gardens: theirs would be each’s primary relationship, while they would continue to see other people. They would tell each other everything about their other lovers. They made a two-year plan, after which they might renew the terms of the agreement. One imagines them shaking on it.

Beauvoir’s success in the agrégation is another matter of legend. She not only passed on her first try, at age twenty-one (making her the youngest person ever to pass), but scored second place out of that year’s group. First place went to Sartre, though he was taking the exam for the second time after having failed the previous year. As Kate Kirkpatrick writes in a new biography, Becoming Beauvoir:

Advertisement

One judge held out for Beauvoir as “the true philosopher,” and at first the others favoured her too. But in the end their decision was that since Sartre was a normalien (someone who had studied at the elite École Normale) he should receive first place.

They were posted, at first, to teaching assignments at lycées in different cities, she in Marseilles and Rouen, he in Le Havre, but they eventually both secured positions in Paris. They took rooms in the same residential hotel in Montparnasse, saw each other most days, and often worked side by side—famously in local cafés like Le Dôme and La Rotonde. They read and edited each other’s work. Beauvoir would have serious, long-term relationships with three other men, as well as shorter relationships with women, and Sartre had many affairs and relationships of his own, but per the agreement, they told each other everything and remained essential partners until Sartre’s death in 1980, drawing around them a network of friends, former lovers, and protégés.

A colleague of Beauvoir’s in Rouen, the novelist and critic Colette Audry, tried to convey the dazzling quality of their conversation to Beauvoir’s first biographer, Deirdre Bair: “I can’t describe what it was like to be present when those two were together. It was so intense that sometimes it made others who saw it sad not to have it.” Beauvoir’s brother-in-law said that “through their constant talking, the way they shared everything, they reflected each other so closely that one just could not separate them.”

At the time that she wrote The Second Sex, Beauvoir was mentioned always in the same breath with Sartre (though the reverse was not true). They were a glamorous and charismatic couple, prominent in the Parisian intellectual world and enthusiastically embraced in the US. She had published L’Invitée (She Came to Stay) and a short book of philosophy, The Ethics of Ambiguity; he had published Being and Nothingness, in which he first outlined the principles of his Existentialist philosophy, as well as No Exit and the novel Nausea. In their press coverage, it was Sartre who was the prodigious philosopher, she the devoted apprentice and popularizer of his ideas. There was some truth in the public gloss, as well as sexism, and to complicate matters for Beauvoir’s later feminist devotees, Beauvoir herself more or less signed on to this view of things: Sartre was the prodigious philosopher, she maintained in her memoirs and many of her interviews after the publication of The Second Sex, and she was not really a philosopher but a novelist.

As their correspondence and respective diaries were posthumously published, beginning in the 1990s, it emerged that Beauvoir probably had a greater influence on Sartre’s thinking than she’d taken—or been given—credit for. Scholars have puzzled over why Beauvoir seems to have disavowed her own ambitions and downplayed her influence on Sartre in the many volumes of her popular memoirs. In Becoming Beauvoir, Kirkpatrick digs deep into the discrepancies between Beauvoir’s diaries and her memoirs, yet suggests a simple reason for her self-deprecation: “Despite her early sense of vocation as a writer, she lacked confidence…. The image of their relationship that has been passed down to posterity reflects Sartre’s self-confidence and her self-doubt.”

A different theory is floated by Margaret A. Simons, a coeditor of the English translations of Beauvoir’s diaries, of which a new volume, Diary of a Philosophy Student, Volume 2, 1928–29, has recently been published. Simons suggests that Beauvoir’s downplaying of her own ambitions and influence was a sacrifice that she deliberately made to protect the legacy of the The Second Sex. She didn’t want readers to think she had written it out of bitterness, or a sense of failure—which is of course what many critics immediately thought about her work of so-called feminine resentment.

Beauvoir researched and wrote The Second Sex between 1946 and 1949. She had not originally planned to write a brick-sized treatise but rather an autobiographical essay about what being a woman had meant to her. In her twenties, she had not been troubled by women’s lesser legal and social status. Her friend Audry has recalled that she was maddeningly certain that her life was as free as Sartre’s. Yet even so, she began to register the ways their freedom was different, or felt different. Before he wrote his first book, when he was merely teaching, Sartre felt like a loser. Beauvoir, by contrast, was “dizzy with sheer delight” just to have a teaching job. “To pass the agrégation and have a profession was something he took for granted,” she would later write, while “it seemed to me that, far from enduring my destiny, I had deliberately chosen it. The career in which Sartre saw his freedom foundering still meant liberation to me.”

You could hastily conclude that this reflected a temperamental difference: Sartre was more ambitious than Beauvoir. But it wouldn’t be true. Beauvoir’s being a philosophy teacher already marked the triumphant fulfillment of an improbably grand ambition—for a woman of her place and time. As she considered what being a woman had meant to her personally, the book became political. Her contemporaries might look at the ranks of the elite professions and conclude that men generally were more ambitious than women, or perhaps just better at most things. But, Beauvoir hoped to demonstrate in the book that swelled to eight hundred pages, that probably wasn’t true either.

Throughout The Second Sex, Beauvoir makes the category “female” disappear and then reappear. Disappear, because, as she argues, when you look across the natural world there is no particular, consistent female role or even physiological definition. It is no more inherently female to serve your mate dinner than it is to kill and eat him—it just depends on your species. Indeed, when you sift through the ways in which people have defined femaleness, and justified male dominance, the arguments vary and contradict one another. Conservatives fret that “woman is losing herself, woman is lost,” Beauvoir writes, while others reassure themselves that “women are very much still women” even in the more egalitarian Soviet Russia. Depending on where you look, Beauvoir notes, femininity is either woman’s eternal and inescapable nature, or it is in danger of dying out if women don’t do a better job of practicing it. How can both of these propositions be true?

And yet the category of female must mean something: Why else were wives not allowed to open bank accounts (until 1965), or women to attend the École Normale Supérieure? Beauvoir reconstitutes “female” as a category, but one whose primary significance is social. There may be no stable definition of femininity, but, Beauvoir shows, the feminine is consistently defined in opposition to the masculine. Oversexed or undersexed, cunning or feebleminded, selfless or selfish: whatever contradictory qualities get attributed to women, even the putatively good ones, end up serving as rationales for why men, not women, should have the bank accounts and ENS diplomas.

In her epigraph to The Second Sex, Beauvoir quotes the little-known seventeenth-century philosopher Poulain de la Barre: “Everything that has been written by men about women should be viewed with suspicion, because they are both judge and party.” By the time Beauvoir worked this idea into her analysis in the mid-twentieth century, her readers were likely to be at least loosely familiar with central concepts in Marx and Freud, both of whom, along with Friedrich Engels, Beauvoir discusses at some length in the book. Readers were ready to receive the idea (whether they liked it or not) that men had a stake—a sort of class interest—in promoting their superiority, and that even reasonable men of science might be unconsciously motivated in their repeated discoveries of women’s inferiority.

An old thought was now more richly resonant: when it comes to their assessments of women’s capacities, men are not impartial—they are interested. For many of her readers, Beauvoir’s analysis helped clear out the vestiges of the notion that male authority over women was divine or natural: it was instead the story of one social group dominating another.

The second volume of The Second Sex, Lived Experience, follows woman through all the phases of life, from childhood through old age. The intimacy Beauvoir achieves on the page is sometimes startling. “During the first three or four years of life,” she writes in a chapter called “Childhood,” “there is no difference between girls’ and boys’ attitudes…boys are just as desirous as their sisters to please, to be smiled at, to be admired.” But soon, boys are pushed toward emotional independence, a process that may look—and feel—harsh:

Little by little boys are the ones who are denied kisses and caresses, the little girl continues to be doted upon, she is allowed to hide beneath her mother’s skirts, her father takes her on his knees and pats her hair.

But “if the boy at first seems less favored than his sisters, it is because there are greater designs for him.”

The girl, meanwhile, is headed for a fall:

When her acquaintances, studies, amusements, and reading material tear her away from the maternal circle, she realizes that it is not women but men who are the masters of the world….

The father’s life is surrounded by mysterious prestige: the hours he spends in the home, the room where he works, the objects around him, his occupations, his habits, have a sacred character…. Usually he works outside the home, and it is through him that the household communicates with the rest of the world: he is the embodiment of this adventurous, immense, difficult, and marvelous world.

This is, of course, a portrait of the educated, professional man’s daughter. What it’s like to realize that your father lacks prestige, or daily feels thwarted in that difficult outside world, is not nearly as well plumbed by Beauvoir, as many critics have pointed out. This is a pitfall of her somewhat freewheeling approach. In Lived Experience Beauvoir must once again conjure the category “female,” this time from the inside, and it involves a lot of moving parts. Drawn together from personal experience, friends’ experience, interviews with women in the US and France, and a small number of sociological surveys about European women, Beauvoir’s generic woman in these chapters is actually a shapeshifter: sometimes working class, though more often middle class, sometimes a lesbian, sometimes a wife, sometimes a professional working woman. She is implicitly a Catholic, white Frenchwoman. Beauvoir has no methodological apparatus that would pass muster with a social scientist; her authority depends on the reader’s acceptance that, although there is no such thing as a generic woman, there is enough common social experience that the category holds, and that Beauvoir can speak for it convincingly. For many readers, she did.

But The Second Sex is not only about women. It’s also, inescapably and no less intimately, about men. In writing about young women’s sexual initiation, she compares it to young men’s:

With penis, hands, mouth, with his whole body, the man reaches out to his partner, but he remains at the heart of this activity, as the subject generally does before the objects he perceives and the instruments he manipulates; he projects himself toward the other without losing his autonomy; feminine flesh is a prey for him, and he seizes in woman the attributes his sensuality requires of any object; of course he does not succeed in appropriating them: at least he holds them; the embrace and the kiss imply a partial failure: but this very failure is a stimulant and a joy.

Writing about wives, she inevitably wrote about husbands:

The husband “forms” his wife not only erotically but also spiritually and intellectually; he educates her, impresses her, puts his imprint on her. One of the daydreams he enjoys is the impregnation of things by his will, shaping their form, penetrating their substance: the woman is par excellence the “clay in his hands” that passively lets itself be worked and shaped, resistant while yielding, permitting masculine activity to go on.

Had men ever been subject to such cool scrutiny by a female author? Beauvoir recalled that Albert Camus, her friend at the time, “bellowed, ‘You have made a laughing-stock of the French male!’” This is, on the face of it, an odd comment, because if there’s one thing Beauvoir does not do, it’s deride men. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, had some fun in A Room of One’s Own sketching the hypothetical intellectual misogynist Professor von X., author of The Mental, Moral, and Physical Inferiority of the Female Sex, whom she pictured with “a great jowl,” “very small eyes,” and an expression that “suggested that he was labouring under some emotion that made him jab his pen on the paper as if he were killing some noxious insect as he wrote.” Firestone, Millet, and Andrea Dworkin at times all turn caustic in their own sketches of sexist behavior. But Beauvoir isn’t one for satire or mischief. Though her primary purpose was to awaken women to a fuller historical and philosophical view of their relation to men, her secondary, equally sincere purpose seems to have been to awaken men to those same relations. There is nothing in The Second Sex at odds with the idea that men and women are—or should be—good-faith comrades in struggles against all kinds of injustice.

If Beauvoir has made men a laughingstock, then, it’s not because she writes derisively, but simply because she has made men visible. The very existence of the book confirms it. Men, no less than women, are potential objects of intellectual investigation, scientific scrutiny, psychological speculation. They’re sitting ducks. The Second Sex was, among many other things, an unprecedented foray into the objectification of men.

Excerpts from the book were first published in the journal that she and Sartre edited, Les Temps Modernes. The issues sold out. Beauvoir received many letters of appreciation, mostly from women, but there was a larger flood of criticism from right and left. A columnist in Le Figaro dismissively summed up the book as “woman, relegated to the level of the Other, is exasperated in her inferiority complex.” (Toril Moi, in Simone de Beauvoir: The Making of an Intellectual Woman, has noted that contemporary commentaries on The Second Sex were particularly characterized by sarcasm.) A writer in L’Esprit criticized its “tone of ressentiment,” and the philosopher Jean Guitton, Kirkpatrick writes, “expressed pain at seeing between its lines ‘her sad life.’”

When her lover Nelson Algren came to visit Beauvoir in Paris in 1949, he was impressed to find that people stared, pointed, and whispered about her in cafés—apparently not kindly. “You’ve made all the right enemies,” he would tell her. Beauvoir also came in for some hate mail, as she would recall:

I received—some signed and some anonymous—epigrams, epistles, satires, admonitions, and exhortations…. People offered to cure me of my frigidity or to temper my labial appetites; I was promised revelations, in the coarsest terms.

What could this be but obscene harassment, politely described?

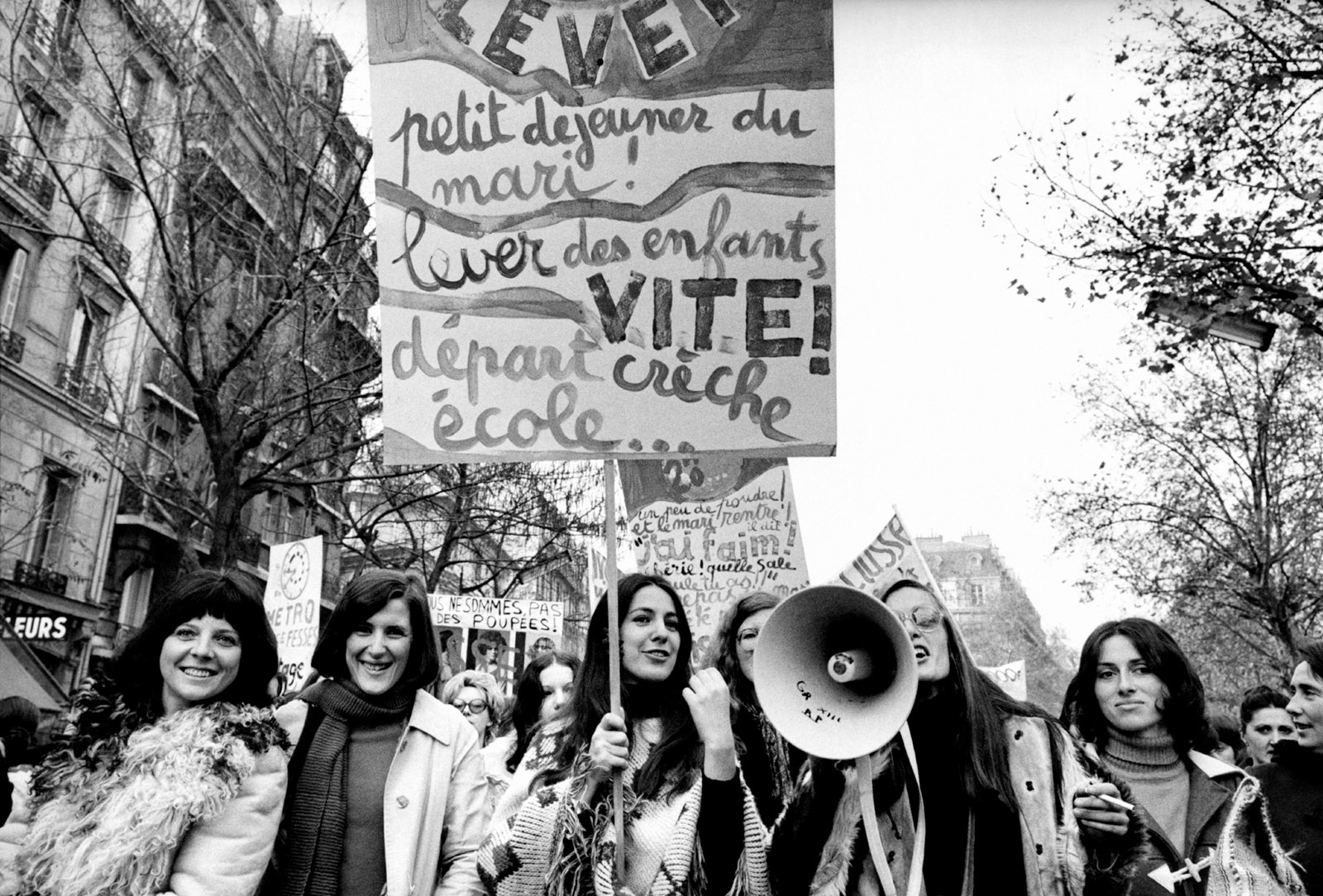

More than twenty years after The Second Sex, a women’s political movement emerged. By then the book and Beauvoir were passé to many young activists, but in 1970 members of the radical French women’s liberation group MLF nonetheless asked Beauvoir if she wanted to join them in their campaigns. She did.

“The situation of women in France has not really changed in the last twenty years,” she told an interviewer. The tide toward equality that she once thought inevitable had not rolled in, “even in left-wing and revolutionary groups and organizations in France. Women always do the most lowly, most tedious jobs, all the behind-the-scenes things, and the men are always the spokesmen.” Though she still didn’t believe in essential female qualities that set women apart from men, she did think that women—whatever exactly they were—needed to organize on their own behalf. It had not been enough to analyze; now Beauvoir exhorted: “Don’t gamble on the future, act now, without delay.”