In 1973 Georgia O’Keeffe accepted a young poet’s help organizing her library at her house in Abiquiu, New Mexico. For seven years, C.S. Merrill spent her weekends with the great painter, who was in her eighties, cranky, and nearly blind, but still a formidable figure, attracting acolytes and interviewers and painting with help from assistants. The younger woman rarely asked questions—“if I wanted to last there,” she was advised, “I must consider it like a medieval court and keep a very formal relationship with Miss O’Keeffe”—but sometimes O’Keeffe would reminisce about her artistic beginnings in New York. She confided that the years before her success “were the best of her career because she was surrounded by people who didn’t care. She was free.” One day, O’Keeffe surprised Merrill by opening a desk drawer to show her a photograph—one of the famous early nude portraits of her by Alfred Stieglitz, when she was “young and in love,” Merrill comments. They were the start of an unparalleled serial portrait of more than three hundred images, made over two decades.

Two recent books examine the lives of Stieglitz and O’Keeffe and their astonishingly productive marriage. Carolyn Burke’s group biography, Foursome, explores the friendship and mutual influence between two creative couples: Stieglitz and O’Keeffe, and the photographer Paul Strand and his first wife, the painter Rebecca Salsbury. At its most intense, in the 1920s, their friendship was charged with excitement and aesthetic inspiration. But it degenerated into a Pinteresque drama of complications, betrayals, and rebuffs, with some surprising third-act reversals. While Burke has four narrative threads to weave—and does so with dexterity—Phyllis Rose, in Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters, has only one, to which she brings her characteristic wit and vivacity, offering a fascinating counterpoint to Foursome.

Stieglitz has no real heir in contemporary American culture. No single figure leads the avant-garde—whatever that is now—with his fervor and authority. A dynamo who energized two generations of art and photography enthusiasts, he brought legitimacy and prestige to American art in its own country, and gave many of the giants of European modernism—including Picasso, Brancusi, and Matisse—their first exhibitions in the US. One artist described Stieglitz’s gallery as “an oasis in the desert of American ideas.”

The novelty in Foursome is seeing Stieglitz always in relationship, rather than embattled and alone, as he has sometimes been depicted, thrashing through a thicket of mostly forgotten conservatives and philistines in the New York art world. He gathered followers—most notably, in the early years, the photographer Edward Steichen, whom he heavily promoted—but often drove them away. Steichen and Stieglitz clashed during World War I, when Steichen argued that Stieglitz’s gallery must take a stand politically against Germany, while Stieglitz (emotionally connected to Germany) insisted on the universality of art. Although they reconciled in old age, Steichen later wrote, “Stieglitz only tolerated people close to him when they completely agreed with him and were of service.”

Of the four artists in Foursome, Stieglitz had the most artistically enriched upbringing. He was born in Hoboken in 1864, the eldest child in what would be a large family. His father, a German-Jewish wool broker and weekend painter, uprooted the whole family in 1881 and moved them back to Germany so the children could complete their educations. Alfred stayed nine years—a Jamesian immersion in European art and manners. Although he had been studying mechanical engineering (his father’s idea) at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin, he eventually switched to chemistry so that he could work with Professor Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, the pioneer of photochemistry. Stieglitz had bought his first camera at nineteen and was obsessed. With Vogel, he mastered his craft and returned to New York in 1890 as perhaps the most technically advanced photographer in the country. After a failed early business venture in photomechanical color printing and a season of moping over his lost European idyll, Stieglitz took on coeditorship of The American Amateur Photographer and launched his career.

For rank-and-file members of the two photographic clubs in New York, as well as for the few art connoisseurs then interested in photography, Alfred Stieglitz swept in like a hurricane. He wrote most of the articles in The American Amateur Photographer, whether technical or critical, and snatched prizes at photography exhibitions. He roamed Manhattan with his first hand-held camera, a Folmer and Schwing 4×5 plate, and took some of his best-known images, including Winter—Fifth Avenue (1893) and The Terminal (1892), which Burke describes as “both a tour de force and a spiritual statement.” Until about World War I, every image Stieglitz created was also an argument for photography as a fine art, rather than a purely mechanical and chemical process or, God forbid, a hobby. At first, this meant promoting the gum and glycerin processes—darkroom brushwork, essentially—that allied photographers with painters. As Rose points out, however, Stieglitz was too attracted to detail to fully embrace the dark, dreamy pictorialist aesthetic of Gertrude Käsebier or early Steichen. After his marriage in 1893 (again, his father’s idea), he used his long European honeymoon as a photographic odyssey—a frustration to his wife, Emmeline, who preferred an elegant shop to a picturesque ruin. Three years later, Stieglitz was asked to lead the Camera Club of New York and its beautiful, far-reaching new journal, Camera Notes. “I had a mad idea that the Club could become the world center of photography,” he recalled.

Advertisement

After Camera Notes came the even more lush and influential Camera Work (1903–1917). Of these years the photography critic Sadakichi Hartmann wrote, “It seemed to me that artistic photography, the Camera Club and Alfred Stieglitz were only three names for one and the same thing.” In 1902, fed up with opposition to his autocratic rule of the Camera Club, he declared the Photo-Secession, a group of artists—Clarence White and Käsebier were early favorites—he handpicked to represent the new direction in photography. Steichen was vacating his studio and suggested Stieglitz show some photographs there. The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, the first of his three galleries, was born in 1905. (This venture is better known as “291,” for its address on Fifth Avenue, even though the gallery moved next door to 293 in 1908.) No plush, no gilt: the starkness of the gallery walls was as arrestingly modern as the art he showed. (Even the famous Armory Show of 1913 was decorated with great leafy garlands and bunting.)

Stieglitz was “always there, talking, talking, talking, talking in parables, arguing, explaining,” as Steichen remembered. He cared little about sales, except insofar as they helped his artists. O’Keeffe recalled her first visit to the gallery in 1908 with classmates from the Art Students League to see a controversial exhibition of Rodin’s sketches of the nude—“Rodin’s drawings struck her as so many scribbles,” according to Burke—but years passed before she returned. Eventually, in 1916, she went alone to see a Marsden Hartley show and found Stieglitz kind and sympathetic. He let her take a drawing home for free.

He had long hoped for a female protégé, a lover, or even, having envied his twin brothers’ closeness, a kind of twin. The birth of his daughter, Katherine, in 1898 had not saved his unhappy marriage; Emmeline helped support the galleries financially but had little else in common with her husband. For a couple of years, Stieglitz had been trying to seduce the painter Katharine Rhoades. Rose observes that Rhoades “was his first try at creating a woman artist.”1 Not only was Stieglitz sexually frustrated—his marriage was almost celibate—but he longed to seize everything that was modern: in this case, the sexual freedom beginning to emerge in Europe and in artistic bohemian circles in New York.

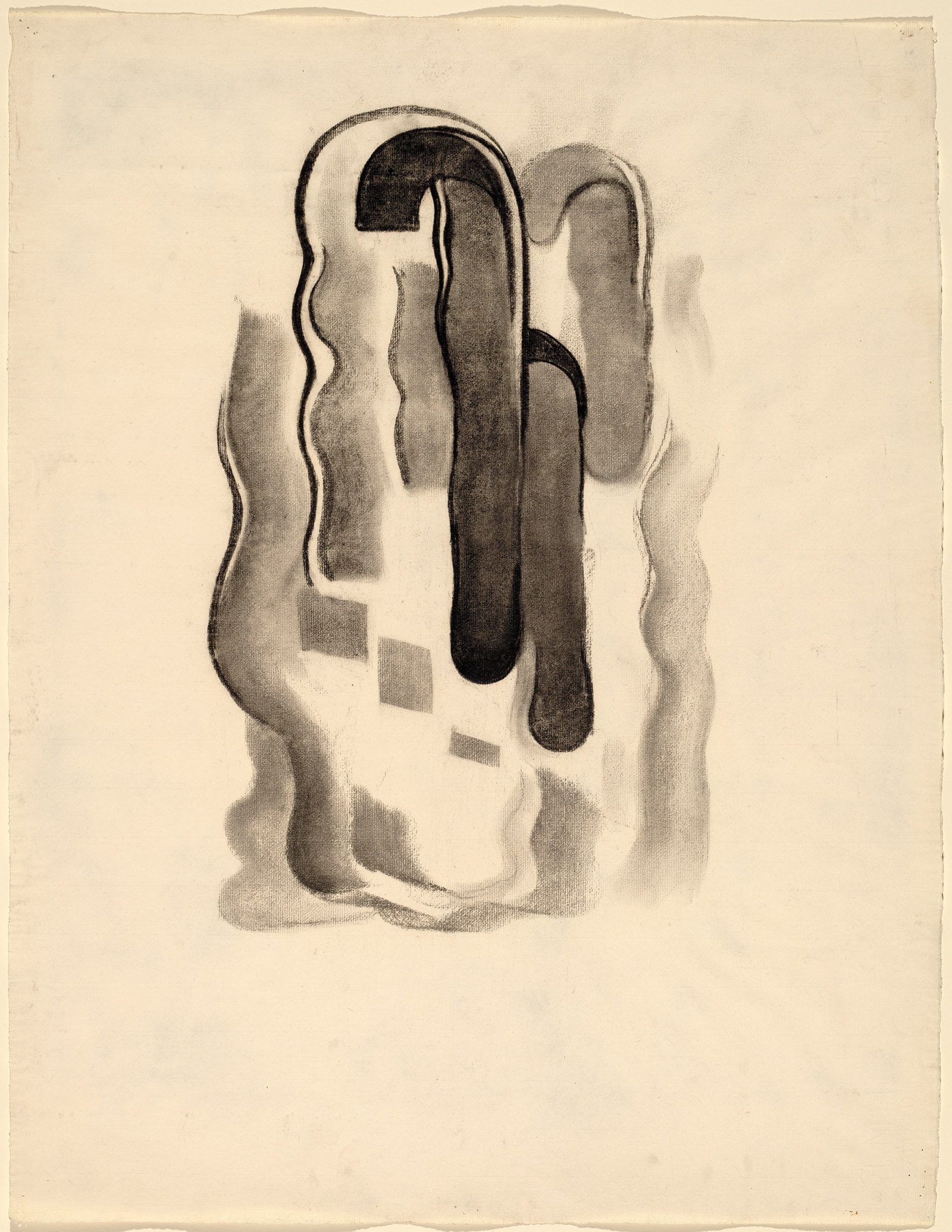

Fittingly, given the geographic distance O’Keeffe put between them for much of their marriage, the big moment for Stieglitz and her arrived when they were far apart. From Columbia College in Columbia, South Carolina, where she was teaching art, O’Keeffe had sent some abstract charcoal drawings she called “Specials” to a close friend in New York, Anita Pollitzer. She asked Anita to keep them private. “At certain moments in our lives we know what we must do, and when I saw Georgia’s drawings, it was such a moment,” Pollitzer recalled.2 She rolled the drawings back up and took them to 291, where Stieglitz exclaimed, “Finally a woman on paper!” “Her line embodied the tactility he revered,” writes Burke; “her swirls gave off a sense of movement.”

It was January 1, 1916, his fifty-second birthday. Without asking O’Keeffe, Stieglitz exhibited ten of the drawings in May, and began a cautious but steady courtship, much of it epistolary, since she had several other suitors and soon left South Carolina to chair the art department at West Texas State Normal College.

O’Keeffe was twenty-three years younger than Stieglitz. “She was completely Other” to him, Rose remarks:

Her style was midwestern, her clothes austere and androgynous. Self-reliant, strong-minded, tart and snappy, she was the free American Girl who had never been to Europe and had no interest in going there.

Her parents were Wisconsin dairy farmers who had relocated their large family to Virginia when Georgia was in her teens. Always encouraged by them to pursue art, O’Keeffe studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and then at the Art Students League, winning the William Merritt Chase prize in 1908 for a brownish, Dutch-inspired still life of a dead rabbit and a copper pot—her last imitative work. Owing to a case of measles and her father’s financial misfortunes, O’Keeffe stopped painting for a few years, then enrolled in art classes at the University of Virginia in 1912, where she was introduced to the composition theories of Arthur Wesley Dow and began moving toward what we would now call abstraction.

Advertisement

At almost the same time that Stieglitz lost Steichen’s allegiance, he gained a new adherent in Paul Strand. Burke does her best with Strand, but he was elusive, often withdrawn into his work, and his side of his long correspondences with Rebecca Salsbury and with O’Keeffe has been lost. Strand had first visited 291 on a field trip with Lewis Hine’s class at the Ethical Culture School and became a habitué. Around late 1914 he brought his portfolio to Stieglitz, who disparaged Strand’s then fashionable use of a soft- focus lens: “You’ve lost all the elements that distinguish one form…from another,” he said. When Strand returned the next summer with a new portfolio of formally innovative urban images, the most “modern” pictures yet to appear among American photographers, Stieglitz announced that he had done something new for photography, and that he should consider 291 his home.

The timing seemed magical. Stieglitz saw Strand as the child of 291, his eye trained by the work and values Stieglitz had presented. But his experiments also spurred Stieglitz’s competitive instincts. Impressed by Strand’s sharp-focus city studies—Strand had rigged his camera so that people on the street would not realize they were being photographed—Stieglitz brought similarly crisp detail to portraits of his entourage and, in the waning days of 291 (the gallery closed in 1917, a cultural casualty of the war), the building’s elevator operator. Hodge Kirnon (1917) demonstrates Stieglitz’s love of creamy midtones and his subtle but arresting geometric forms, in this case the window that frames his subject’s head from behind, a glowing trapezoid.

It is hard to look away from a Stieglitz print. Harder still to imagine that he and Strand were, in these years, reluctantly adapting to a new process, palladium, since platinum—the highly customizable “prince of all processes,” as Stieglitz called it—had military applications and became unobtainable for photographers during the war. (Hodge Kirnon is a palladium print, as are most of Stieglitz’s nudes of O’Keeffe.) Burke notes that Stieglitz describes his new ideas as “just the straight goods,” nearly the same terms he applied to young Strand’s: “The work is brutally direct. Devoid of all flim-flam; devoid of trickery and of any ‘ism.’” No more apologies for the mechanical aspects of the art. The machine aesthetic lay ahead.

Strand’s prints had also stirred O’Keeffe, who was soon conducting an intimate correspondence with both men. It must have taken all Stieglitz’s self-control to allow this infatuation to burn itself out. But by the time O’Keeffe returned to New York in 1918, the field was more or less clear for him. He separated from his wife and lived with O’Keeffe in New York City and at the Stieglitz family’s summer place at Lake George in the Adirondack foothills until 1935, when, feeling smothered by Stieglitz and his large family and resentful of interruptions to her work, O’Keeffe began to spend part of each year in New Mexico. (“I don’t know why people disturb me so much,” she once wrote.) They married in 1924, after his divorce.

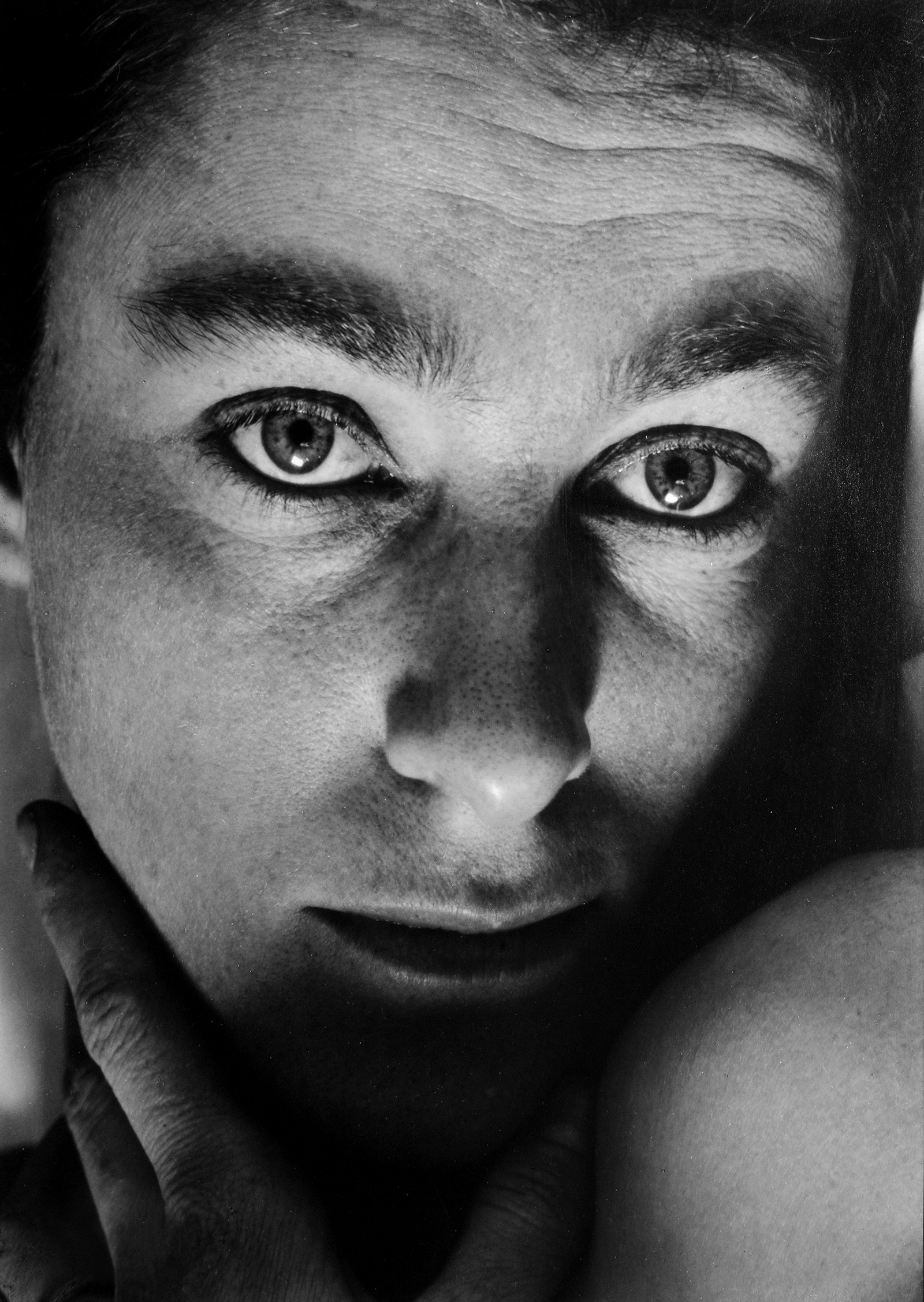

When they were together, they couldn’t keep their hands off each other. Even during much of Stieglitz’s long affair (from the late 1920s on) with Dorothy Norman, a New York activist and art patron, he and O’Keeffe made love often, and their letters are full of references to their intense sexual connection. “It even seems to be my only memory of you,” she wrote to him in 1922, “two bodies that have fused—have touched with completeness at both ends making a complete circuit…. The circle with two centers—each touching the other.” The earliest nudes in Stieglitz’s composite portrait of O’Keeffe, created before the two became lovers, were part of their courtship: “I’ll make you fall in love with yourself,” Stieglitz told her.

These frank images contributed to the lasting critical perception that O’Keeffe’s paintings were representations of female sexual anatomy and desire. When they were first exhibited in 1921, they made her a celebrity. “From the beginning,” Rose writes, “Stieglitz sexualized her work and she allowed it.” Critics seemed to relish alluding to women’s sexuality as openly as the times permitted. O’Keeffe was hardly acknowledged as an artist, so thrillingly was she a Woman. “Her great painful and ecstatic climaxes,” wrote one critic, “make us at last to know something the man has always wanted to know…. The organs that differentiate the sex speak.” (The visual analogy of O’Keeffe’s close-up flowers to female genitalia sometimes obscures their other obvious analogy: the photographic close-up.) Annoyed, O’Keeffe fell back on pragmatism: “One must sell to live,” she told a friend, “so one must be written about and talked about whether one likes it or not.”

Both Stieglitz and O’Keeffe could be melodramatic. O’Keeffe would have run a sword through anyone standing between her and her easel, yet Stieglitz “liked to think of her as frail,” Rose points out. He used the excuse of her occasional breakdowns and exhaustion from work to talk her out of having children. Although they remained emotionally enmeshed, O’Keeffe came to feel that she had ceded too much territory to him. Her annual decampment to New Mexico redressed the balance. Stieglitz was forced to accept her independence, but it shook him.

For readers of Foursome new to the Stieglitz/O’Keeffe legend, the big surprise may be Rebecca Salsbury—“Beck”—who practically climbs out of the book and gallops off. Strand met her during the war, and they married in 1922. Beautiful and adventurous, with a boyish streak, she had felt stifled in the wealthy New York circles in which her widowed mother moved. She longed to do something important. Her paternal roots were in the West: her father had managed and toured the world with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Rebecca and her twin sister were born in 1891 during the show’s London engagement.

Being among artists intoxicated her. At repeated intervals in Foursome, Rebecca moans that she is not an artist. Strand complains to Stieglitz that Rebecca is not an artist. Stieglitz throws up his hands. She tried poetry, photography, watercolor still lifes. Comparing her own fledgling paintings with those of O’Keeffe, propped up after a day’s work at Lake George, did not help. But everyone around her maintained that art was the highest calling, and Salsbury needed a cause. She modeled for both men. Strand often brought his camera unusually close to her in these portraits, and she felt that their long, grueling sessions together were collaborative. She missed them when Strand moved on to other ideas. Rose argues that “Strand’s work seems to have shown to both O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, among other things, the abstracting potential of the close-up.” But his portrait series of Beck struck the other couple as too close to their own cherished portrait project.

Stieglitz did not mention his bruised feelings over the series, though a sense of betrayal seems to have lingered. Beck, increasingly alert to Stieglitz’s prickly nature, later suggested that Strand develop new images of her at home rather than at the club, where Stieglitz could have seen them. Burke teases out these moments of conflict and irritation between the men, while Rose emphasizes the creative spur they gave Stieglitz. His photographs of Salsbury swimming in Lake George in September 1922 are almost as erotic as his nude portraits of O’Keeffe, though without the impression of postcoital languor. He had thought these outdoor shots were just experimental, and they do seem playfully improvisational; but while printing them, as he told a friend, he realized they were extraordinary: “Eye-openers. Am surprised myself because while she was here I imagined I had totally failed.”3

Now it was Stieglitz and Salsbury who indulged in a clandestine correspondence. Salsbury did not allow the flirtation to go further. Instead, she made herself a handmaiden to Stieglitz—typing, organizing, donating money, running errands for O’Keeffe. Salsbury provided essential support at Stieglitz’s second gallery, the Intimate Gallery (1925–1929), but the presiding spirit of his third gallery, An American Place (1929–1946), was Dorothy Norman, O’Keeffe’s bête noire. Norman admired O’Keeffe and Strand as artists, but guarded her turf at the gallery.

Despite her intimacy with Stieglitz and the placating letters she wrote him on Strand’s behalf, Salsbury was much more interested in cultivating her friendship with O’Keeffe, who dazzled her. Aloof by nature and wary of Stieglitz’s followers, O’Keeffe warmed to Salsbury over the years. During the summers at Lake George they painted and did chores together. O’Keeffe included some of Salsbury’s pastels in the April 1928 show she curated at the Opportunity Gallery. (Like O’Keeffe, Salsbury chose to exhibit under her maiden name.) She told Beck her artistic world had beauty and power in it, though she could probably see the work was stylistically indebted to her. The pinnacle of their affection was a 1929 trip alone together to the home of Mabel Dodge Luhan, patron of the avant-garde, near the art colony in Taos, New Mexico—an idyll of painting, drinking, and mild mischief that O’Keeffe took pains to conceal from her elderly husband. Salsbury taught O’Keeffe how to drive.

Strand’s increasing social engagement after the mid-1920s bored Stieglitz: he had little patience for photography as a political tool. He told one critic who had praised Strand’s 1929 show at the Intimate Gallery, “You would not have written about Strand as you did if you had seen my work first.” In 1932 he offered Strand and Salsbury a two-person show at An American Place, but failed to promote the exhibition or print a catalog. He even left Strand to hang the prints himself. They had been shown the door. Typically, Strand felt liberated, while Salsbury wrote to Stieglitz and tried to reconcile the men.

Some biographers have assumed that Salsbury and O’Keeffe were lovers. There is no evidence for this. But O’Keeffe’s pinched heart did expand a little, here and there, in her letters to Salsbury, especially when Salsbury’s marriage to Strand came apart in the early 1930s. “Imagine that it is two years from now,” O’Keeffe wrote,

and in the meantime don’t do anything foolish. Only time will make you feel better—and don’t talk about it to people if you don’t want to…. Why should you be expected to explain your personal life to anyone—It is rather difficult to even explain it to oneself.

Salsbury remained in New Mexico after her divorce, happily remarried, and became something of a Taos character, as well as a successful painter. Like O’Keeffe, she felt deeply inspired by the culture and landscape of New Mexico. Marsden Hartley had introduced her to reverse oil on glass, which became her métier. From the 1930s to the early 1960s, she exhibited her work throughout the West. She was an artist, after all.

O’Keeffe honored Beck’s friendship with one last favor. At eighty, she drove the body of Bill James, Salsbury’s second husband, to Albuquerque for cremation, then brought the ashes back to Taos to be scattered. Salsbury had become disabled by rheumatoid arthritis and could never have undertaken the six-hour drive: “Nobody else has come anywhere near that unforgettable act of friendship.”

The other women artists Burke has written about—Mina Loy, Lee Miller, and Edith Piaf—struggled for autonomy and sometimes sank into alcoholic despair. O’Keeffe and Salsbury managed their relationships more successfully, in both cases by living separately (partially or completely) from the powerful men they had married. After Strand’s death, his third wife, the photographer Hazel Kingsbury Strand, said of his prints, “They were his women, they were his children, they were the love of his life.” O’Keeffe inherited a modern art collection worth $150 million from Stieglitz and survived him by forty years. After his death in 1946, she told Dorothy Norman to clear out of An American Place. She closed the gallery and poured herself into the effort of gathering and sorting Stieglitz’s immense archive and donating its contents to carefully chosen institutions throughout the country (a fascinating story in itself), eventually giving the Key Set—the best prints of his 1,600 best images, as she saw it—to the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Then she moved full-time to New Mexico.

In her eighties, she published a memoir, followed by a selection from Stieglitz’s composite portrait of her. In her introductory essay, O’Keeffe described her husband as “a very exciting person,” later clarifying, “He was either loved or hated—there wasn’t much in between.” Finally, she burst out that she preferred his artwork to Stieglitz himself:

I believe it was the work that kept me with him—though I loved him as a human being. I could see his strengths and weaknesses. I put up with what seemed to me a good deal of contradictory nonsense because of what seemed clear and bright and wonderful.

-

1

His last attempt was his lover Dorothy Norman, whom he taught photography, and who turned out to be a sensitive and intelligent portraitist. Her archive is housed at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson. ↩

-

2

O’Keeffe knew that her friend was collecting materials for a biography of her, but withdrew approval after reading Pollitzer’s completed manuscript. Perhaps her own early letters, from which Pollitzer included long extracts, embarrassed her. A Woman on Paper: Georgia O’Keeffe was published in 1988, after both women’s deaths. ↩

-

3

Rose studied photography for several years, and her discussion of Stieglitz’s and Strand’s work is sensitive and well-informed. But Burke can be quite alert: while most historians reiterate that Stieglitz included no portraits of Dorothy Norman in his 1934 retrospective, ostensibly to mollify O’Keeffe, who had been sickened by the affair, Burke catches sight of an “odd” double-exposure of Norman’s face entitled Dualities, which echoed the title of Norman’s recent book. ↩