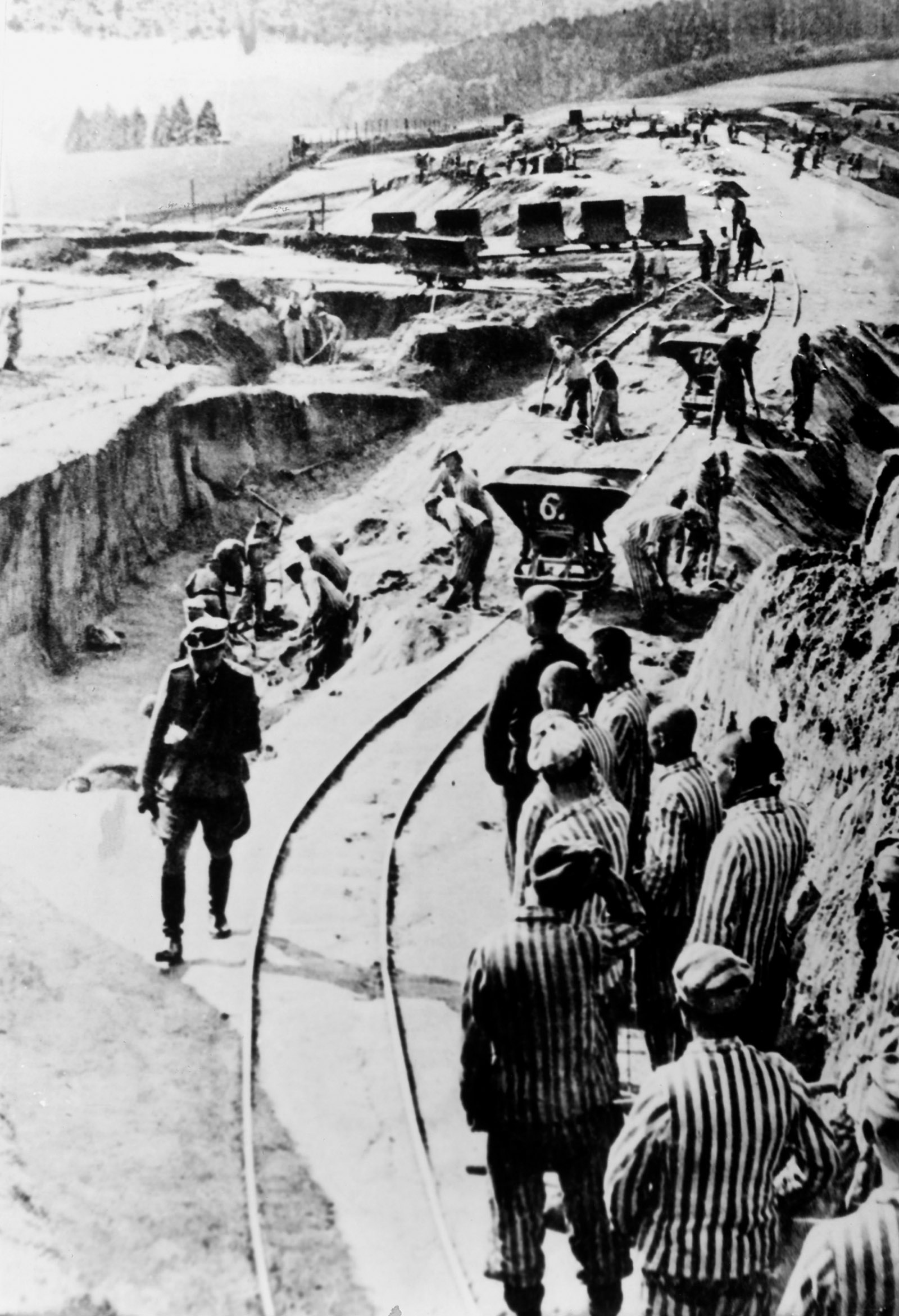

On May 5, 2005, Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero journeyed to Mauthausen, a small Austrian town picturesquely situated on the Danube. A solemn task awaited him: commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp on the hill above the town where, over the course of seven years (1938–1945), almost 200,000 prisoners had been held, including some seven to nine thousand Spaniards who, having defended the Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), went into exile and then were captured by the Germans when France was defeated in 1940 (many had joined the French army). Although 14,000 Jews were liquidated in Mauthausen, it was not set up as an extermination camp. Its purpose was to exploit the slave labor of “incorrigible” and “unredeemable” political prisoners from a wide array of nations, as well as of smaller numbers of gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and criminals. The harshest of the Nazi labor camps, it operated under conditions so brutal that approximately 65 percent of the inmates perished.1

Rodríguez Zapatero’s presence at the anniversary marked a significant shift in his country’s official recognition of the suffering of its citizens who had been deported and killed as part of the Nazi genocide. As Sara J. Brenneis explains in Spaniards in Mauthausen: Representations of a Nazi Concentration Camp, 1940–2015, her painstaking and definitive book on the subject, for many decades those victims were “unacknowledged ghosts in contemporary Spanish society.” The Franco dictatorship—which was complicit in the Nazi persecution of its opponents2—had zero interest in remembering them, but they did not fare much better during the intricate transition to democracy after the Caudillo’s death in 1975.

The success of that transition hinged, at least initially, on the “pact of silence” reached between Franco’s successors and those who had resisted his authoritarian and bloody rule: it amounted, Brenneis writes, to a “decision not to enter into recriminations about the Civil War and dictatorship.” Even when it came time for a reckoning with the past, public attention was focused on the vast internal repression of the Franco years, leaving scant space for those Spaniards who had been tyrannized in Nazi concentration camps abroad. And yet, as Brenneis notes, from 1995 onward, as part of the “historical memory movement” of survivors, intellectuals, and grassroots organizations determined to disinter the uncomfortable truths of the Franco era, the Spanish voices of those who had experienced the Nazi camps started to be heard.

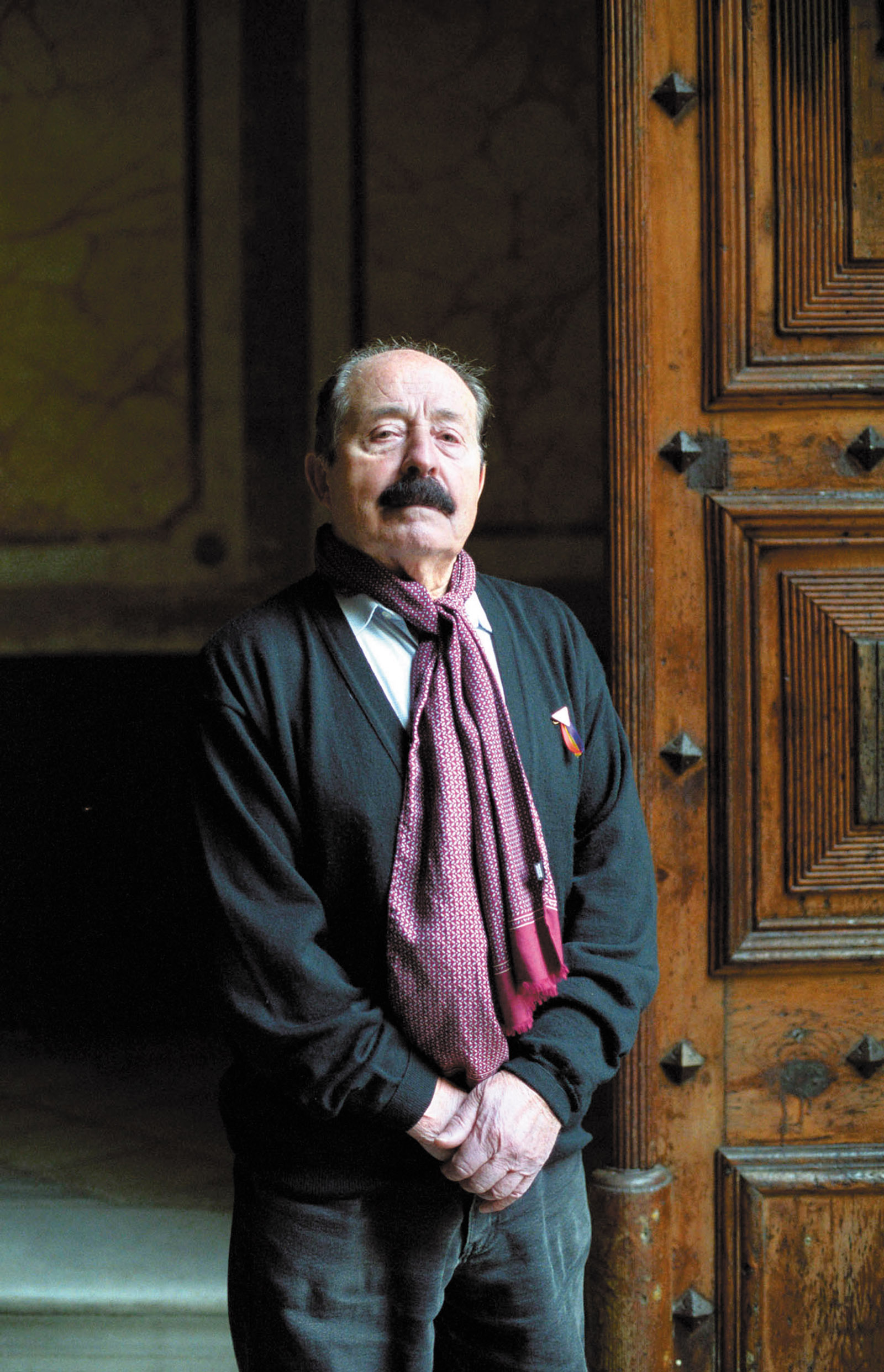

The most striking, charismatic, and popular voice was that of the Catalan activist Enric Marco, whose rise to fame and precipitous fall is recounted by the Spanish author Javier Cercas in his fascinating book The Impostor: A True Story. Until the moment Marco’s life crumbled, he was, according to Cercas, the embodiment of all the virtues of the past that Spain had wanted to brush aside, an “omnipresent demigod in the history of the country.” According to Marco, he participated, at the age of fifteen, in the victorious July 1936 defense of Barcelona against the fascist insurrection and, a few months later, in the futile but daring attempt to wrest control of Mallorca from Franco’s forces. He then enlisted in the Republican Army, fighting valiantly, often behind enemy lines, until he was wounded and evacuated from the front.

When the Nationalist forces seized Barcelona in early 1939, Marco did not flee into exile like many combatants but stayed behind to organize the resistance, escaping the police several times. After he was finally forced to clandestinely leave the country for Marseilles, his plans to continue the struggle for liberty were thwarted when he was captured by the Vichy police, who turned him over to the Gestapo. Sent to the Flossenbürg slave labor camp in Bavaria, he endured with dignity the horrors that we know all too well from books, films, and oral history.

After the American army liberated that camp in 1945, Marco returned to Spain and for the next thirty years courageously opposed the dictatorship, confronting so many dangers that when democracy arrived, he was elected secretary-general (first in Catalonia and then nationally) of the anarchist-inspired Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), at the time one of Spain’s most important trade union organizations, and also elected head of the Amical de Mauthausen, the Barcelona-based organization created by former Catalan inmates of Nazi concentration camps.3 In that capacity, he indefatigably wrote articles, gave interviews, talked to innumerable students in schools, coordinated protests, and received the most prestigious medal awarded by the regional Catalan government. And when, on January 27, 2005, Spain’s Parliament for the first time commemorated Holocaust Day, sixty years after the liberation of Auschwitz by Soviet troops, Marco was the main speaker, his words so movingly delivered that he was, according to Cercas, “carried from the Parliament in triumph,” like a rock star or soccer champion.

Advertisement

Only one more event was necessary to crown Marco’s ascent to glory: he was scheduled to speak in the presence of the prime minister at the May 2005 tribute at Mauthausen, representing not only the former Spanish prisoners but numerous other nationalities whose citizens were mistreated, tortured, and executed there. It was not to be. A few days before the ceremony, Benito Bermejo, a historian specializing in the fate of Spaniards deported to Nazi concentration camps, revealed documentary proof that Marco had lied about crucial aspects of his heroic exploits: “he had not left Spain clandestinely, he had not been arrested in France and sent to Germany, he was not a deportado.” Instead, like thousands of other Spanish civilians, Marco had left Spain voluntarily at the end of 1941, accepting a job in Kiel with a German company, Deutsche Werke Werft, as part of an agreement between Franco and Hitler to send Spanish workers to Germany; Cercas writes that it was “intended as a contribution to the war effort of the country attempting to impose fascism across Europe by fire and sword.”

The press, both Spanish and international, covered the story extensively: far from being a symbol of the resistance and the fierce will to survive Nazi repression, the president of the association dedicated to remembering the victims was a collaborator, a fraud, a villain. Rather than having a prominent part in the sixtieth-anniversary commemoration, Marco—having confessed that he had never been interned in Flossenbürg—found himself expelled from the Amical, unanimously reviled as a charlatan who, besides fooling and betraying his family, friends, companions, and the public, had also given fodder to Holocaust deniers, who could point to him as evidence that the Nazi genocide had not happened.

Marco’s blatant deception was met not only with outrage but with stupefaction. How on earth had he managed to inveigle so many people, including experts and survivors, for so long? And if he had not realized that lies of this magnitude would someday be exposed, what else in his life might he have invented?

Among those asking themselves these questions was Cercas, who was so drawn to the case that he toyed with the idea of writing his next book on Marco. Still, beset by an “inchoate dread” of the “profound connection” he felt to such a supreme fabulist, given that he was a fabulator, a novelist with “license to lie,” Cercas hesitated for a few years before setting up a meeting with “the great pariah.”4 Marco used the occasion to pathologically defend himself as a paragon of virtue, a sacrificial victim. It was true, he said in a torrential apologia pro vita sua, that if he had not literally been in any concentration camp, he had nevertheless been jailed by the Nazis in Kiel and accused of high treason against the Third Reich. Who could deny that he had been a tireless champion of freedom in the struggle against Franco, had fought for the rights of workers at great risk to his life, and had done more, with his eloquence and zeal, to educate the public and especially the young about the forgotten past than any of the real survivors? If he had made a small, stupid mistake, he had done so for a good cause.

The horrified Cercas abandoned the project, deciding that he could not write about a man who was “a monster. A complete monster!” And yet in 2013, still torn between revulsion and attraction, he ended up interviewing Marco again, this time at great length over many months, in an attempt to ferret out the truth.

From the very start of their relationship, Marco makes clear that by cooperating with Cercas, he expects to “regain his voice, to take off the muzzle…to tell the truth, or at least his version of the truth…to all those who had trusted him, acclaimed him, loved him.” And Cercas, afraid of the slightest hint that he might be justifying Marco’s colossal con game, makes equally clear that the book will neither absolve nor rehabilitate him. These divergent aims determine the bifurcated structure of The Impostor. Marco’s life is presented in chronological order in chapters that alternate between his presentation of his deeds and misdeeds, and Cercas’s conscientious analyses of the veracity of his account. Thus the chapter in which Marco describes his brave resistance to the Franco dictatorship is followed by Cercas implacably contesting that myth, proving that Marco was passive and undistinguished during the long years of Franco’s rule. Marco, he affirms, “is not a symbol of exceptional decency and honor in defeat, but everyday indecency and degradation.” Like most people in Spain, Marco was full of fear, dedicated to self-preservation, “a member of the vast, silent, cowardly, grey, depressing majority who always say Yes [to oppression],” rather than a leading participant ready to risk saying No in turbulent, dangerous times.5 It is an abject truth that Marco, of course, does not want to admit.

Advertisement

A singular tension therefore pervades the back-and-forth narrative, in which the cunning Marco tries to distort and conceal what really happened and Cercas, with his incantatory prose, strips away every fraudulent ruse. He is careful, all the while, to be fair and judicious. Suspecting that “this tissue of lies was naturally molded around truths,” he takes pains to unearth proof that the impostor had, contrary to everybody’s belief, fought at the front for the Republican side (though it was false that he had been wounded or been part of a group of anarchist guerrillas). When Marco cites his months as a prisoner of the Germans in Kiel to substantiate his claim that he was an intrepid anti-Nazi agitator, Cercas verifies that he was incarcerated for seven months (not the nine that Marco recounts), but adds that he was exonerated of all charges, found to be blameless and inoffensive, and consequently was not in the least heroic. And Cercas traces the roots of Marco’s monomaniacal narcissism, his yearning for admiration, to a childhood marked by trauma, homelessness, and neglect.

Readers will be impressed by how scrupulously Cercas pursues the facts, in obvious contrast to Marco’s incessant obfuscation. By questioning his own motives and methods at every step, by making sure to separate what is indubitable from what is conjecture, he shows us how to systematically dismantle any web of lies, constructing a model of “reflective skepticism” from which we have much to learn in our era of rampant conspiracy theories and viral Internet falsehoods. By the end of the book, Marco can no longer vindicate himself as “the victim of an unspeakable lynching,” for he has been denied the use and abuse of the word verdaderamente (truthfully), which he repeats constantly as he spins his tall tales. Readers of the otherwise mostly admirable English translation by Frank Wynne will not be able to fully understand this tic: when Marco first talks to Cercas, he employs the word verdaderamente twice, but both instances have been rendered by Wynne as “honestly” rather than “truthfully.” This may sound more colloquial, but it deprives us of experiencing Marco directly as he uses his favorite adverb to convince people that he should be trusted.

This matters, because The Impostor is much more than a masterfully written investigative report that unmasks a consummate con man. What makes it unique is that Cercas—intrigued by Marco’s unremitting fictionalization of his life—will avail himself of that fraud to meditate at great length and with originality on the nature of truth (la verdad) and its relationship to diverse forms of storytelling, a passion that has defined his major literary works.

Cercas is best known for hybrid works that apply fictional strategies and techniques to real-life events. Soldiers of Salamis (2003) is inspired by the true story of a Spanish Republican soldier who spares the life of a fascist ideologue and poet, even though Cercas makes sure that we do not know which parts of it are invented and which derive from history.6 In The Anatomy of a Moment, as rigorously researched as The Impostor, he examines three very different politicians who thwarted the coup d’état that almost managed, on February 23, 1981, to terminate Spain’s transition to democracy.7 Cercas insists in The Blind Spot, a book-length essay, that Anatomy, besides being a history book, an essay, a journalistic chronicle, and “a whirl of parallel and counterpoised biographies,” is also a novel.8

His latest work, El Monarca de las Sombras, is, like Anatomy, yet another novel-without-fiction, probing the enigma of Manuel Mena, Cercas’s great-uncle, who was killed at the age of nineteen in the Battle of the Ebro in 1938.9 That this relative fought for the fascist cause that Cercas vehemently detests forces him to question his own writing of the book—a process of self-scrutiny that is similar to what we find in The Impostor, whose construction is dissected as Cercas tries to resolve the question of the distance between a novelist like himself, “a liar who tells the truth” and makes his living doing so, and someone like Marco, who thrived for decades by building his biography out of falsehoods. Cercas explores this distance (and perilous proximity) by returning to a rich intellectual tradition that includes Plato, Plutarch, Ovid, Montaigne, Stendhal, Flaubert, Wilde, Tolstoy, Vargas Llosa, Magris, and, above all, Cervantes.

Isn’t Marco, after all, like Don Quixote, a man who invented an epic life for himself because he could not stand his sorry, mediocre, entirely ordinary existence? And aren’t novelists like Cercas akin to Don Quixote and Marco, artificers of an alternative universe assembled from lies? Cercas observes that each novelist, like Marco, is

utterly unsatisfied with life…[and] refashions it according to his desires…[as] a way of disguising reality, a way of protecting oneself from it or curing oneself of it. Like Marco, the novelist invents a fictional, hypothetical life, in order to hide his real life and live a different one, to process the humiliations and the horrors and the inadequacies of real life and turn them into fiction, to hide them, in a sense to avoid knowing or recognizing himself.

This does not, however, let Marco off the hook, because “the rules of a novel are different from the rules of life,” and Marco’s mendacities constitute an act of violence against human coexistence, a lack of respect for his fellow human beings, as well as an aesthetic aberration, since rather than revealing through his stories a novelistic truth that is “profound, ambiguous, contradictory, ironic and elusive,” the melodramatic life he has constructed is sentimental and shallow, the essence of kitsch and fraudulent beauty. As Cercas realizes this, he also understands that it is his mission to “save” Marco by forcing him, like Don Quixote at the end of Cervantes’s novel, to awaken to the reality of his embarrassing, pedestrian existence, to kill his splendid false self so he can glimpse, if only for a moment, the face and fate he has been evading all his life.

Cercas fervently believes that such a moment of deliverance is possible for anyone. In The Anatomy of a Moment he quotes Borges, who wrote that “any life, however long and complicated it may be, actually consists of a single moment—the moment when a man knows forever more who he is.”10 It is not clear if, by the end of The Impostor, Marco has attained that catharsis of self-recognition and repented, as he proclaims, or if he is slipping away again, putting on one more mask. Cercas, who worships at the altar of ambivalence and uncertainty and “radiant darkness,” seems not to care that we can never really know the answer.

Sara Brenneis only mentions The Impostor in passing in her book, since she is unconcerned with sham accounts of concentration camps when so many real ones are ignored. But in an interview in The Volunteer, she raised two objections to it.11 The first is that Cercas, who revels in acting as a political and literary provocateur, believes that Spain’s historical memory movement is dead, has become “a passing fad.” She is right to consider that injudicious at best; Cercas’s book proves that the efforts to investigate and preserve the memories of Spain’s disturbing past are vibrantly alive, and recent political events, as well as films like the award-winning documentary The Silence of Others (2019) and The Photographer of Mauthausen, a fictional recreation of that camp (2018; available on Netflix), corroborate her judgment.12 In fact, the very existence of Cercas’s book depends on the success of the historical memory movement. If the tenacious lives recounted by Brenneis had not informed Spanish audiences, however insufficiently, about what they really endured in Mauthausen, a book about someone who fakes that experience would have lacked an indispensable background.

Her second complaint is that Cercas concentrates on the fraudulent Marco instead of rescuing “incredible, life-and-death accounts of men and women who were deported to the camps,” even if she accepts that some fictional approaches to Mauthausen keep the public memory of that suffering alive.13 Her frustration is understandable: having spent years studying all manner of texts (memoirs, oral history, fictional recreations, and, more recently, even a comic strip and a Twitter feed) that make visible and permanent stories that have been “distant” and “ephemeral,” she must find it grating to watch Cercas hoard the spotlight with the tale of a false survivor. But she does not seem to comprehend how The Impostor tells a deeper and hidden truth about Spain, one that complements her own labors and further justifies the need for her book.

It was the disregard with which the survivors of Mauthausen were treated over decades that opened a space for someone like Marco to be successful. As Cercas hunts down the contours of Marco’s counterfeit existence, he also exposes the perverse void at the core of Spain’s reaction to its past that turned Marco into a hero and that Brenneis denounces. Marco was able to flourish because of the “culpable credulity” of people who “wanted to listen to the lies that the champion of memory had to tell.”

The Impostor continues a search into the Spanish character that has consumed Cercas for most of his literary career. Obsessed with the unresolved moral dilemmas posed by the Franco dictatorship and especially its aftermath, he has shown himself determined to puncture the myths and impostures that his compatriots have nurtured in order to veil a shameful past (for instance, the myth that almost everyone in Spain, in one way or another, opposed Franco, or that when the restored democracy was threatened, people rushed to defend it). And just as Cercas hopes that his book will save Marco by forcing him to recognize the truth, he also hopes it can be part of the salvation of Spain, by demanding that the country recognize the colossal collective failure behind its willingness to be duped by a con man of such epic yet picaresque proportions. It is not only Marco who has to be held accountable, but the land and history that spawned him, which makes The Impostor a book that is woefully relevant well beyond the frontiers of Spain.

Brenneis and Cercas agree that a national reckoning with the Spanish past is long overdue. And both of them emphasize that in the morass of that past, there are real heroes whose example can console and guide our frail and damaged humanity. And so, paradoxically, does Marco. Despite his incessant lies and crimes against memory, who can doubt that he was telling the truth when he inspired schoolchildren by assuring them that “a man may be humiliated, brutalised, treated like an animal, yet in a moment of madness and supreme courage, he can reclaim his dignity, though it should cost him his life, and [that] such moments were within the reach of everyone, and that it is these moments that define and save us”?

This Issue

November 21, 2019

The Defeat of General Mattis

The Muse at Her Easel

Lessons in Survival

-

1

Mauthausen was the main camp in a network of some forty-nine subcamps scattered in the vicinity. Because the Nazis destroyed the documentation, it is not possible to determine the exact number of detainees or the death toll, but most experts agree on the figures mentioned above. See Gordon Horwitz, In the Shadow of Death: Living Outside the Gates of Mauthausen (Free Press, 1990), and David Wingeate Pike, Spaniards in the Holocaust: Mauthausen, the Horror on the Danube (Routledge, 2000). The estimate of 14,000 Jews killed at Mauthausen is from the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ↩

-

2

Brenneis quotes, among others, Antonio Vilanova, who wrote in his book Los Olvidados (1969) that Ramón Serrano Suñer, Franco’s brother-in-law and Spain’s foreign minister, had met with Hitler in Berlin in September 1940 and “incited…the German authorities to maximize their cruelty with the trapped Spanish republicans,” who were left stateless, without protection from their country. ↩

-

3

Not to be confused with the Amicale de Mauthausen, which, under the name l’Amicale des déportés politiques de la Résistance de Mauthausen et de ses kommandos dépendants, was formed in France in 1945 by survivors of that concentration camp complex. ↩

-

4

This fear of encountering a doppelgänger can be traced all through Cercas’s work, most notably in a story, “La Verdad de Agamenón” (2006), in which an author called Javier Cercas switches places with a man of the same name and identical physique and ends up, like Golyadkin, Dostoevsky’s character in The Double, exiled forever from his previous existence. The story serves as an ironic “epilogue” to a collection of journalistic commentaries about politics and literature. ↩

-

5

Cercas is referring to Camus in L’Homme révolté. ↩

-

6

Soldiers of Salamis, translated by Anne McLean (Bloomsbury, 2003); reviewed in these pages by Colm Tóibín, October 7, 2004. Regarding how fiction and reality blend, see Diálogos de Salamina: un paseo por el cine y la literatura (Barcelona: Tusquets, 2003), a book-length conversation between Cercas and David Trueba, who directed the film version of the novel, especially pp. 19–21. ↩

-

7

The Anatomy of a Moment, translated by Anne McLean (Bloomsbury, 2011). ↩

-

8

The Blind Spot: An Essay on the Novel, translated by Anne McLean (London: Quercus, 2018). ↩

-

9

Lord of All the Dead, translated by Anne McLean, has just been published in England by Quercus and is scheduled to be published in the United States by Penguin Random House in January 2020. ↩

-

10

“A Biography of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz (1829–1874),” in Jorge Luis Borges, Collected Fictions (Penguin, 1998), p. 213. ↩

-

11

The Volunteer, a newsletter published by the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, Vol. 35, No. 4 (December 2018). ↩

-

12

See Omar G. Encarnación’s excellent essay “Spain Exhumes Its Painful Past,” NYR Daily, August 24, 2018. That need to confront past atrocities has accelerated under the leadership of the Socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez, who won the most recent Spanish elections and has just managed to finally move Franco’s remains from the Valley of the Fallen, the monument/ tomb he built for himself, to a private family crypt—a significant, albeit symbolic, victory for memory. ↩

-

13

For the ways in which the fictionalization of concentration camp life can deliver an enduring and searing representation of the captivity experience, see my essay “Political Code and Literary Code: The Testimonial Genre in Chile Today,” in Some Write to the Future: Essays on Contemporary Latin American Fiction (Duke University Press, 1991). ↩