At the end of a qat party, typically close to sunset, there comes a moment when the effervescence settles, conversation slackens, and thoughts turn quietly inward. This Solomonic pause—Yemenis call it lahzat Sulayman—serves as a cue. Guests rise from their cushions; hosts slip back to their own pursuits. It is a time to be alone. Cathinone, the stimulating compound in the fresh shoots and leaves of the qat bush, at this stage induces a calm, crisp focus that drivers find useful for long trips, and students for cramming.

One imagines Tim Mackintosh-Smith retiring to the library in his centuries-old house in Sanaa, picking up a well-thumbed classic, and pondering the story of the Arabs—or rather, as he suggests in the introduction to his erudite and discursive new book, of Arabs, for as he persuasively explains, the definite article implies more solidity and cohesion than its subject may merit. Mackintosh-Smith is unusual, and not only because few English gentlemen would in this modern age choose to spend four decades living in far-off Yemen, a wildly rugged country that is now in the throes of its own darkest age. Unusual too is that although he might be called a superb Arabist, as a diligent student and ardent lover of the language, and might also be called a fine historian, as a dogged seeker of truth and a skilled storyteller, he is not a professional at either.

At times Mackintosh-Smith appears a keen Orientalist in the style of those nineteenth-century autodidacts who combined a love of gritty travel “in mufti” with a bookish taste for philology. At others he seems not so much to echo as to inhabit the authors he cites, such as the often laconic tenth-century Baghdadi geographer and historian al-Mas’udi or the towering intellect Ibn Khaldun, who in the fourteenth century served half a dozen warring, conspiring princes between Granada and Damascus but composed his greatest work, the Muqaddimah, during a prolonged hejira among Berber tribesmen in the remote mountains of what is now western Algeria.

Holed up in Sanaa with a civil war raging around him, Mackintosh-Smith finds himself “unintentionally impersonating” the Arab sage in his retreat, ruminating on the perennial clash between settled and nomadic peoples and on the rise and fall of dynasties. Ibn Khaldun described how Yemen’s ancient Sabean kingdoms fell to Bedouin predation; today, Mackintosh-Smith writes, the pattern “repeats itself…outside my window, where gun-slinging tribesmen from the northern highlands”—the Houthis—“have been unleashed on the capital of Saba’s successor by an ex-ruler pursuing a vendetta.” He adds, “So too, mutatis mutandis, in Iraq, Syria and Libya, two-thirds of a millennium on from Ibn Khaldun.”

Mackintosh-Smith enjoys another affinity with the Arab past. He spent a decade trotting the globe in the company of Ibn Battuta, the peripatetic fourteenth-century Moroccan whose travels make Marco Polo, a near contemporary, seem a mere package tourist. Mackintosh-Smith’s astute, funny, and serendipity-spiced trilogy—Travels with a Tangerine (2001), The Hall of a Thousand Columns (2005), and Landfalls (2010)—is a classic of modern travel literature, retracing nearly the entire 75,000 miles Ibn Battuta covered, from Astrakhan to Zanzibar and from Beijing to Timbuktu.

This pedigree and inclination make Arabs an unusual book. For one thing, Mackintosh-Smith defines his subject as connected far less by a common race or history than by speech. If, as al-Mas’udi declared, telling the story of Arabs is like stringing a necklace with gemstones, the thread from which it all hangs is the Arabic language. In old Baghdad, it was said that when wisdom descended from the heavens it was carried by the brains of the Greeks, the hands of the Chinese, and the tongues of the Arabs. In modern times, Tunisia’s first post-revolution president, Moncef Marzouki, has explained that unlike other communities Arabs inhabit not a land but a language. “I think in Arabic; therefore I am an Arab,” declared Abdallah al-Alayli, a twentieth-century Lebanese lexicographer and religious scholar.

This book is not, despite the title, quite a history. It starts with the first recorded mention of Arabs, in an inscription left by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in 853 BC that brags of his victory over a certain Gindibu, with the capture of a thousand camels. And it carries on to the present, with American-made bombs falling on the author’s adopted city. But rather than retelling the long Arab saga in full or raising quibbles with academic historians who have covered this broad sweep, such as Philip Hitti or Albert Hourani, Mackintosh-Smith sets out instead to fill in the gaps they left, to embellish the tale in bolder colors, and to arrange it in a more attractive and revealing way. He is not so much a chronicler as an engaging curator, guiding readers around a fascinating exhibition, pointing out lesser-known objects, and casting new light on burnished masterpieces.

Advertisement

Inevitably, this rambling approach leaves some corners unexplored. In a book that notes that the Prophet Muhammad’s revelation, beginning around 610 AD, marks merely the midpoint of Arab history, one might expect more consideration of pre-Islamic Arabia. Mackintosh-Smith does paint a broad-brush picture of the Greco-Roman era’s division of the Arabian peninsula into three provinces—Arabia Petraea, Arabia Deserta, and Arabia Felix—and of their largely nomadic inhabitants. As an adoptive Yemeni he is keen to rebalance our understanding in favor of the “felicitous” southern end of Arabia. We hear much of the ancient Sabean and later Himyarite kingdoms there, and of powerful Yemeni influences on the culture in which Muhammad developed. It is curious, for instance, that the Kaaba, or cube, at Mecca that he made the centerpiece of his new faith seems to have been one of several such shrines scattered across southern Arabia, often containing a cosmopolitan roster of deities to worship. It is interesting too that one native cult, whose adherents were called hanifs, recognized a single god sometimes known as Rahman, terms that were both refashioned in the Koran.

Yet we find only the briefest mention of such famous pre-Islamic Arabs as the Roman emperor Philip the Arab (who reigned from 244 to 249 AD), or of his illustrious contemporaries Odaenathus and Zenobia, king and queen of Palmyra. (In fact, we hear little of women in general, though this reflects the Arab sources more than the author.) Hira, an Arab city in Mesopotamia that served as the capital of the Lakhmid dynasty (Arab vassals of the Sassanian Empire who ruled circa 300–600 AD), receives repeated attention: it is enlightening to know that in order to ensure the loyalty of tribal allies, its rulers kept no fewer than five hundred of their sons hostage.

But we hear little of the rival Ghassanid dynasty in Syria that served Byzantium, and almost nothing of the Nabateans, the rich and illustrious Arabic-speaking builders of Petra in Jordan, or of the far northern Arab tribes who populated yet another spectacular and now-ruined pre-Islamic desert city, Hatra. It would have been good to learn more about the Jewish Himyarite king Yusuf As’ar. Better known as Dhu Nawas, he ordered a massacre of Christians at Najran, in what is now southern Saudi Arabia, in 518 AD, which seems to have prompted the negus of Aksum, a Christian ally of Byzantium, to send a fleet across the Red Sea to invade Yemen. It would be churlish, however, to dwell on oversights or a paucity of names and dates. Arabs is a hugely ambitious book. Full of diverting anecdotes, revealing details, and pithy asides, it rewards in so many other ways.

We read, for instance, that after the arrival of Islam and the rise “like a soufflé” of an Arab empire stretching from Spain to Sindh, it took some time before the caliph decreed that Arabic would be the sole language of official records. The order from the Umayyad ruler Abd al-Malik (who reigned at Damascus from 685 to 705 AD) was said to have followed his outrage at hearing that one of his Greek scribes, finding nothing else with which to thin his ink, had pissed in the pot. Mackintosh-Smith speculates that whatever the truth of the tale, it was this bureaucratic decision, as much as the Koran or the power of Islam, that made Arabic the language of common use across such a vast area. Otherwise it might have gone the way of tongues that were not imposed on or adopted by the subjects of other nomads-turned-world-conquerors, such as the Mongols and Turks, or that slipped into largely liturgical use, such as Coptic or Sanskrit.

The reach and persistence of the language have been extraordinary. Deep in the Jordanian desert, a two-thousand-year-old Arabic graffito scratched in stone records a hurried flight from a sudden torrent in the season of Suhayl, which is to say under the star Canopus, in late January. Mackintosh-Smith tells us that to this day, a proverb among the local Bedouin warns, “When Suhayl’s overhead, trust not the torrent-bed.” In 774 AD an English king, Offa of Mercia, minted gold coins modeled on Arab dinars, the standard of the time. They had “Offa Rex” stamped on one side and on the other an Arabic inscription familiar to any Muslim, la ilaha illa Allah—there is no God but God. Conversely, we find that the first coins minted in Spain by its Arab conquerors bore the same phrase in Latin: In Nomine Domini: Non Deus Nisi Deus Solus.

Advertisement

In explaining the relative decline of Arab science following the European Renaissance, Mackintosh-Smith cites the repeated bans on printing imposed by the Ottoman Empire, beginning as early as 1485. Rather than simply reprimand the Turkish overlords for self-defeating narrow-mindedness, or repeat explanations offered by other scholars (such as fear that errors in sacred texts might be mechanically replicated, or that scribes and calligraphers might lose their jobs), he suggests technical and aesthetic reasons. Compared to the blockish Latin alphabet, the Arabic script presents devilish difficulties to typesetters. Because its elegant letters are linked, taking different forms at the beginning, middle, or end of a word, a complete Arabic font requires in excess of nine hundred characters. Small wonder that early efforts with movable type proved so ugly on the page that printed texts were long viewed “rather as tinned spaghetti is in Italy.”

The present age gets its own share of entertaining stories and sharp pronouncements. On a Yemeni roadside, stuck with a dead car battery and at a loss when a kind motorist stops but has no jumper cables, Mackintosh-Smith borrows a pair of Kalashnikovs from passing tribesmen to use as a bridge to connect the batteries. The car starts, and he ruefully remarks that perhaps guns do have some positive benefit. One of the gunmen corrects him: “Their benefit is killing.”

Mackintosh-Smith is as well versed in Arabic literature as in English, but also skilled at bringing the electricity of the one into the other. He captures a typically Bedouin whiff of irreverence in an eighth-century prayer that hints that their new, single god is a bastard:

Between us, Lord, things really should be better—

Like old times, when You made our weather wetter.

So send us rain, O you with no begetter!

A satire current in the eighth century was more direct about the shortcomings of a commander who dallied with captive slave girls instead of pursuing the charge:

You fought the foe, then fun and games allured you double-quick:

Your sword stayed in its scabbard while, instead, you drew your prick.

By contrast, a short-reigned tenth-century caliph’s poetic evocation of a boozy Baghdad dawn sounds strikingly modern:

Another glass!

A cock crow buries the night.

Naked horizons rise of a plundered morning.

Above night roads: Canopus,

Harem warder of stars.

Amusing as such passages are, the book’s greater contribution is to our understanding of the broader sweep. Mackintosh-Smith has the courage to make bold choices—such as to leave the “rich and distracting background” of Islam out of the picture as much as possible, and to focus instead on the mundane. This is not to say that he underplays matters of faith; his picture of the setting in which Islam arose is brilliantly sharp. But he is refreshingly unromantic about human motives, noting, for instance, that the Sunni–Shia schism was—and in many ways still is—a family feud between descendants of Muhammad rather than a struggle over dogma.

Mackintosh-Smith makes a persuasive case for the primacy of the Arabic language, beginning with his description of how nomadic, tribal bards stitched a multilayered web of words across vast expanses of desert:

Arabic poems are metaphorical structures, dwellings made of metrical units called asbab (“tent ropes”) and awtad (“tent pegs”), which in turn make up hemistichs called simply shutur (“halves”) or masari’ (“leaves of double doors”), two of which together build a line of poetry, a bayt (“tent, room, house”). As a group, the ancient Arab poems are thus the Knossos, the Pompeii of pre-Islamic Arabia.

The language contained plenty of stuff to adorn such structures. Mackintosh-Smith delights in enumerating the terms for different types of terrain that one tenth-century lexicon arranged in poetic order. In just one section, we find nafanif (“lands that lengthen journeys by their ups and downs”), sabasib (“‘flowing’ plains”), dakadik (“sandy plateaux between mountains”), fadafid, ’atha’ith, sahasih, and more. Along with eighty synonyms for honey, two hundred for beards, and eight hundred for swords, classical Arabic contains precise terms for different types of farts, for the sound of locusts munching on crops, and for each space between the fingers of the hand.

By emphasizing language, rather than race or tribe or religion, as the essential marker of what it has meant to be Arab, Mackintosh-Smith exposes some of the grain beneath the paint, the ways in which pre-Islamic notions have survived to the present day. Before Muhammad’s revelation, the word din—which later meant religion or faith—evoked a sense of earthly obligation, akin to dharma for Hindus. Sunnah, which later came to mean the personal practices of the Prophet, had earlier applied to the hallowed ways of ancestors in general. Both notions had to do with a sense of primal order. This is one reason, he suggests, why Muslims later became so reverent of the person of Muhammad: “Denying God is a matter of theology; denying the Prophet goes against something much older and deeper.”

At the same time, it is from the Arabic language that the Koran—the first Arabic book—draws its power. The various literary elements, as Mackintosh-Smith convincingly demonstrates, were not so new, but

the genius of Muhammad (or, if you like, Allah) put them together in a heady cocktail, in which the political theology of South Arabia was mixed with the metaphysical theology of imported Christianity and Judaism, and poured out together in the supernatural, spellbinding language of the old ’arab poets and seers.1

The power of this language can work for evil as well as good:

Outside my window, now, preachers and poets are inspiring fourteen-year-old boys to go off and get themselves blown to pieces…. When they are killed, they explain that it had to happen because it was divine will, and persuade their parents to rejoice at their “martyrdom,” to smile through their tears as they bury their children, as my neighbor has just done to the remaining bits of his son.

It is not just that “high” Arabic, “rich, strange, subtle, suavely hypnotic, magically persuasive, maddeningly difficult,” retains its incantatory power. The persistence of diglossia—the coexistence of radically different registers in the same language—helps explain Arab contradictions. The preservation of a classical, theoretically immutable written tongue that is common to all Arabs alongside the myriad, endlessly evolving colloquial languages that they actually speak has sustained a notion of Arab unity that still inspires hope though it may be much battered. But this is, says Mackintosh-Smith bluntly, an imagined bond, as well as a bind: “The reality is dialect, and disunity. Arabs have never been united in speech, or in any other way, only in speeches; never in real words in the real world, only on paper.”

Yet while it is true that the Arab “family” has always been divided—even the glorious moment of Muhammad’s triumph at Mecca, when in an oft-repeated Arabic phrase “their word was united,” lasted just a few years—it might be said that the intensity of these family squabbles has amplified the Arab voice in the world. If the Arabs are relevant today, it is partly because no other language, aside from English, has spread as far and wide as Arabic. English contains some two thousand Arabic loan-words (from alcohol and coffee to jackets and sofas), Bahasa Indonesia three thousand, Spanish four thousand. The vocabulary of modern Swahili is about half Arabic, Farsi is 30 percent Arabic, Turkish 26 percent, and Hindi and Urdu not much less.

In modern times, it is for quarrelsomeness that Arabs have been best known. Mackintosh-Smith cites a recent UN report that notes that although Arabic speakers make up just one in twenty of the world’s people, they account today for 58 percent of its refugee population and 68 percent of battlefield deaths. In trying to answer the question of why this is so, he gives short shrift to well-worn arguments about the legacy of colonialism. This is not from lack of sympathy. He aptly describes the Balfour Declaration—which expressed Britain’s commitment to make Palestine “a national home for the Jewish people” while promising that “nothing shall be done to prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities”—as a logical impossibility, “like saying you would build a new reservoir without prejudicing the people of the villages that would be flooded.”

Mackintosh-Smith’s refusal to blame current atrocities on colonialism appears to stem instead from an unromantic desire to stimulate self-reflection:

If the British in Palestine were measurably wickeder than the British in Egypt, and the French in Algeria wickeder than both, then so too are the Egyptians in Egypt today, where the current regime can imprison a young man for two years for wearing a “No Torture” T-shirt.

Expanding on the argument that Arab divisiveness is not new but rather a constant from the earliest times, he finds himself falling back on Ibn Khaldun:

If, for example, Hafiz al-Asad resembled a grocer, his son Bashshar looks like the eye-doctor he trained in London to become. And yet they and their fellow autocrats are no less raiders and herders than the raw desert dynasts of Ibn Khaldoun’s classic theory. Their power is taken and held by raiding; their people—their ra’iyyah, “subjects,” or in its first meaning, “private flock”—are controlled by herding, a herding of minds.

He might have added that the persistent glorification of the ghazw—the raid—as a legitimate means of struggle has tended to create more instability than would, arguably, the drearier business of planning and prosecuting actual wars. He might also have noted that within the Ibn Khaldunian cycle, there is always a certain synchronicity between periodic collapses of urban civilization—such as the domino-like toppling of leaders in the Arab Spring—and the rise in the wilderness of wild, fanatic groups such as ISIS, an ingathering of modern nomads from across the world aiming to shock “civilization.” Persistent too throughout Arab history has been a certain destabilizing bipolarity. The language itself, notes Mackintosh-Smith, contains an unusual number of words that mean both one thing and its opposite, echoing the tension between “high” and “low” languages, between ideals and realities, or between settled and nomadic peoples, hadar and badu.2 He quotes Muhammad al-Jabiri, a trenchant modern Moroccan philosopher, as calling the ability to hold two opposing opinions at once “the essence of being Arab.”

A lesser writer—and virtually anyone in academia—might shy from venturing onto such politically perilous ground. But Mackintosh-Smith has seen too much to be delicate and remains too curious to resist being provocative. In the current state of the Arabs, with refugees pouring into other countries “as if Arab history is spiralling into a grim parody of its own beginnings” as a people cast into the desert, he finds an elusive reflection of a desire to keep hold of something essential. His own idea of an Arab “essence” is a certain innate instinct to resist, to remain aloof. This is not a matter of some sort of common Arab mentality but rather an intangible magnetism, a group genius or tribal daemon:

They fight against the times and maintain that ever-present past, the eternal yesterday; they do not want to fix the broken clock. They know that to become part of the present continuous, the blur, would be to enter the biggest super-hadarah ever, to become more like everyone else on earth. And a recurring characteristic of being ’arab, or Arab, right from the start, has been that of being marginal, independent, not like everyone else. To the extent that one enters hadarah, civilization, one ceases to be “Arab” in one of the word’s oldest senses.

And who would want that?

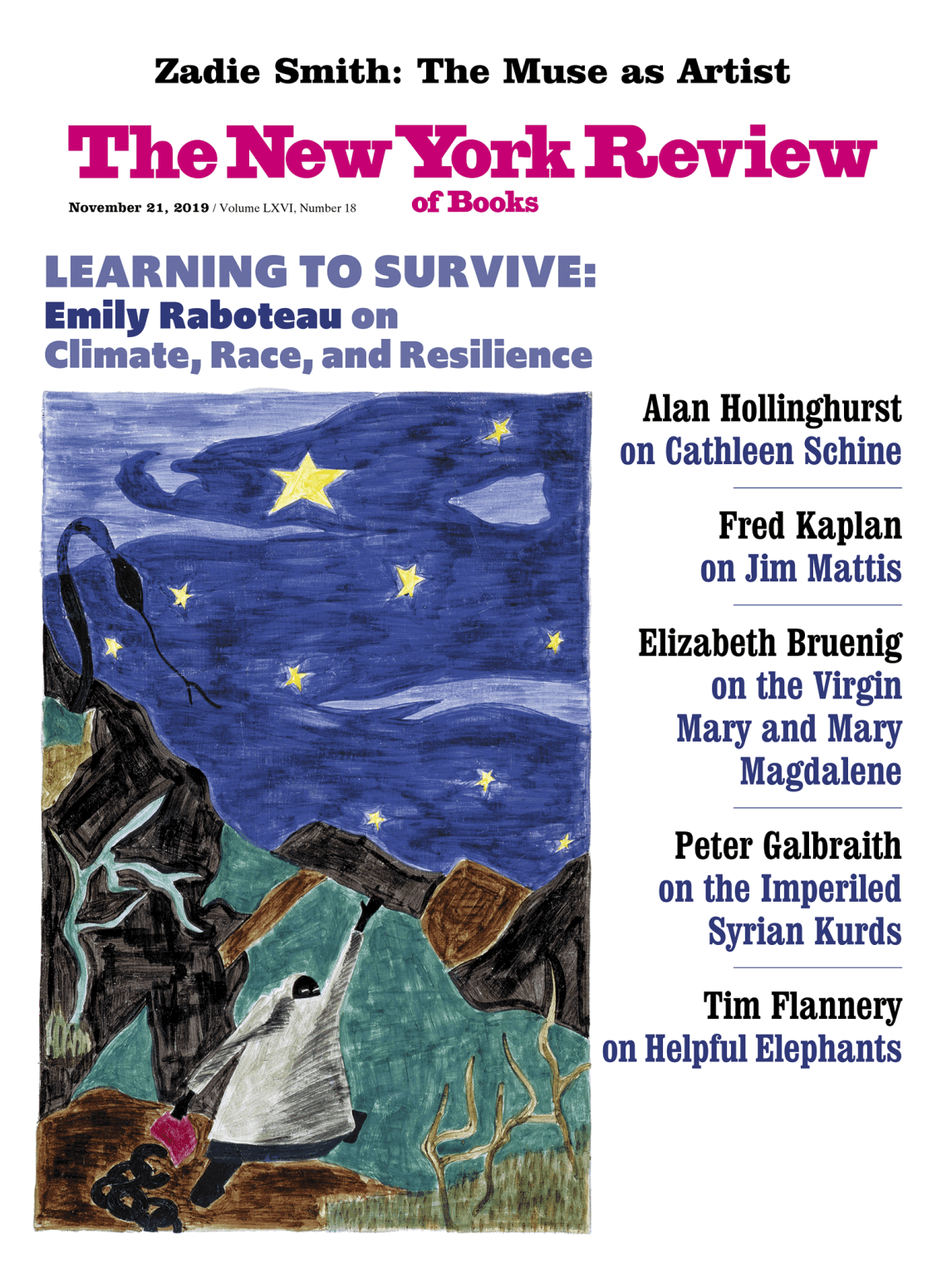

This Issue

November 21, 2019

The Defeat of General Mattis

The Muse at Her Easel

Lessons in Survival