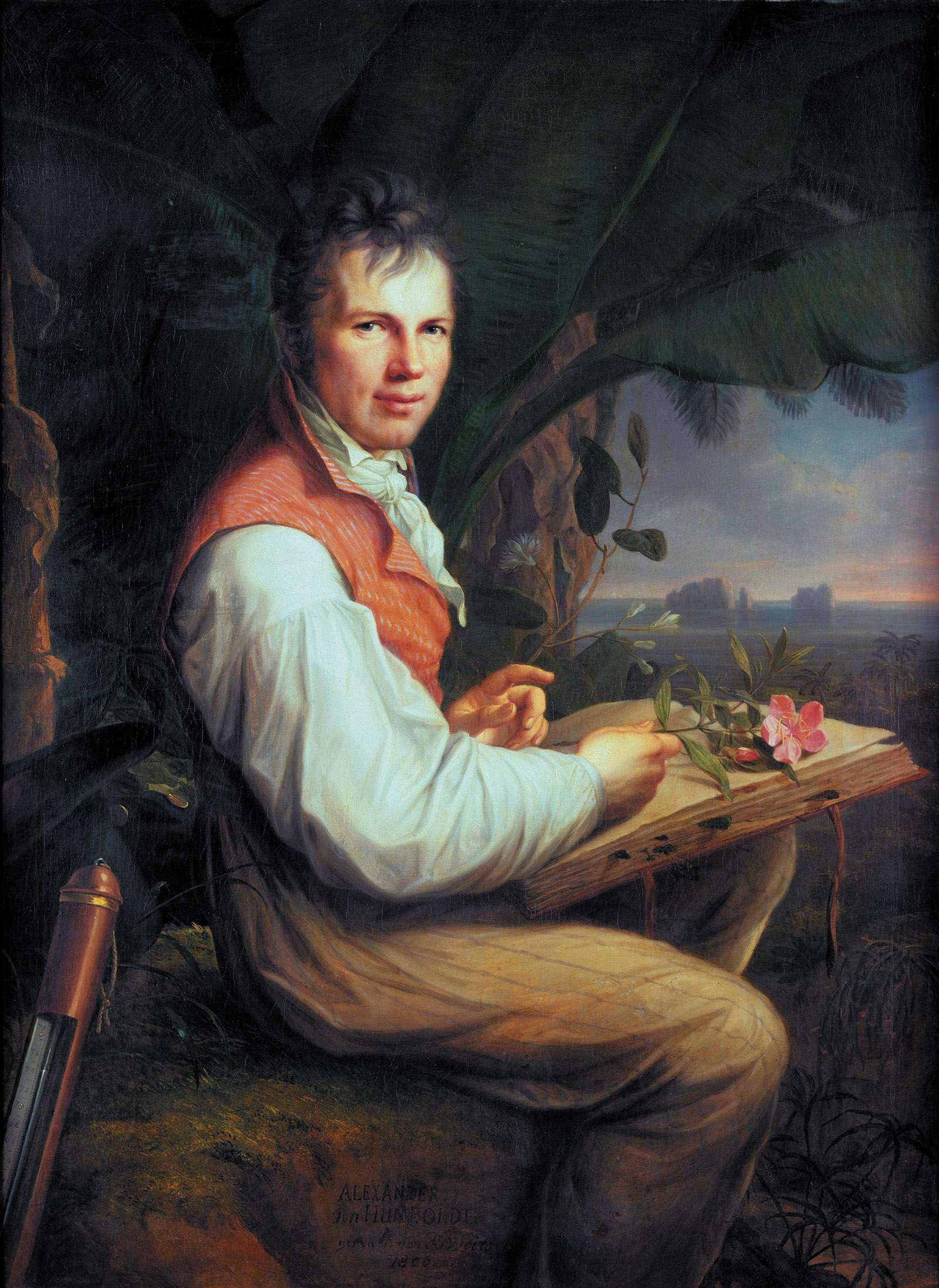

Alexander von Humboldt was born in 1769, the same year as Napoleon, to whom he was formally introduced in October 1804, after his return from five years of intrepid exploration in the Spanish Americas, and whose elaborate coronation as emperor he observed in Paris two months later. Fearing that he still looked a bit rough (“It won’t do to look as though one had gone to the dogs”), Humboldt purchased a fine embroidered cloak for the public celebrations.

Appearance mattered. In 1804 Humboldt’s departure for Europe at the end of his adventure through what was then called the Kingdom of New Spain had been postponed so that he could sail from Cuba to the United States, where President Jefferson wanted to shake the hand of the most celebrated scientist of his time. Jefferson, who had recently purchased from Napoleon a vast swath of land from Montana to New Orleans that nearly doubled the size of the United States, also wanted Humboldt’s advice. No educated man knew more than he did about the previously unexplored regions lying beyond the country’s new border in the southwest.

Jefferson, who kept up a correspondence with his visitor for the next twenty years, described Humboldt as “one of the greatest ornaments of the age.” Charles Darwin signed up for his life-changing voyage on the HMS Beagle in 1831 as a direct consequence of reading Humboldt’s seven-volume (and never completed) Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent. Goethe, who delighted in Humboldt’s company and conversation while sharing many of his wide-ranging interests, had young Ottilie in his novel Elective Affinities exclaim, “How I wish that one day I could hear Humboldt talk!”

Death did not diminish Humboldt’s reputation. On September 14, 1869, ten years after his state funeral in Berlin, the centennial of his birth was celebrated across the globe. Andrea Wulf, whose admirable The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World* emphasized his tremendous influence on nature-writing and the science of climate change, lists just a few of these events in her introduction to her edition of his Selected Writings, a compilation from his immense body of work that is slanted toward Humboldt’s studies of the natural world:

There were parties in Buenos Aires and Mexico City, as well as in Melbourne and Adelaide. In Moscow Humboldt was hailed as the “Shakespeare of sciences” and in Alexandria in Egypt fireworks illuminated the sky. In Berlin 80,000 people trudged through torrential rain to celebrate the most famous resident of their city…. In New York 25,000 people marched along Manhattan’s cobbled streets which were lined with flags and colourful bunting…. Humboldt’s fame, the Daily News in London reported, was “in some sort bound up with the universe itself.”

Here was celebrity on a scale that has rarely been witnessed, which makes it all the more extraordinary that today, despite the warm reception given to Wulf’s biography, Humboldt’s name is one that many people still struggle to connect with specific achievements. Those of us who can manage to locate the Humboldt Current (off the coast of Chile) may hesitate for a moment before dismissing the bold claim made by the town of Humboldt, South Dakota, that the celebrated Prussian traveled alongside the railway builders “on their way west to the land of the buffalo and the Indian.”

Myron Echenberg in Humboldt’s Mexico is skeptical of such “hyperbolic but ahistorical efforts to appropriate [Humboldt’s] name,” given the brevity of his stay in the US. But he is justified in protesting the scant attention Wulf gives to the subject of his book—Humboldt’s year in Mexico, between March 1803 and March 1804—in her otherwise detailed account of his time in the Spanish Americas. It is also largely absent from Maren Meinhardt’s enthralling new account of Humboldt’s life.

Such an oversight is strange, especially since the famous series of talks that Humboldt began delivering to European audiences in 1827—free of charge, open to both sexes and all classes—was clearly inspired by the enlightened lecture system that he had admired while living in Mexico City. His talks aimed to provide a summary of everything that was known in natural science, and, most importantly, how it was all interconnected. They ranged from astronomy to the earth’s interior, from mountain ranges to ocean currents, from the distribution of plants and animals across the globe to the place of human beings on it. Large audiences were attracted by Humboldt’s gift for helping them comprehend the unimaginable, such as the speed of light (which takes thirty-one years to reach earth from the glitteringly visible Dog Star, Sirius, and 94,000 years from the remotest nebulas).

Today, it’s curious to read the Prussian traveler’s praises for Mexico City’s sky as more exquisitely transparent than any in Europe. Humboldt was equally enchanted by the city’s architecture, declaring that “no city in all of Europe…appears more beautiful than Mexico.” The country’s greatest source of wealth also excited his interest. “It is grotesque that one should be unable to profit from fame,” the constantly impoverished Humboldt complained to his older brother in 1824 after learning that his enthusiasm for Mexico’s mining potential had inadvertently encouraged English financiers to invest £3 million in Taxco’s silver mines. Six years later, the Mexican silver bubble burst, and Humboldt realized how lucky he had been.

Advertisement

Echenberg’s research is far from perfect (Charlotte Diede, the young woman with whom Humboldt’s brother, Wilhelm, corresponded for twenty years after a single encounter, is renamed Charlotte Hildebrandt and misidentified as his mistress), but his fondness for digression brings some surprising rewards. We learn, for example, that the near-naked workmen at the Taxco mines frequently tried smuggling small pieces of silver out in clay cylinders lodged in their anuses. While it’s hard to justify the space given in his pages to the Mexican artist Diego Rivera and the American silver designer William Spratling, Echenberg does well to alert us to the danger Humboldt faced in writing objectively about a remote country owned and controlled by King Carlos IV of Spain, who provided him with a passport for his travels there.

Humboldt was courageous, in such circumstances, to denounce as unacceptable the monopoly of Iberian interests and to state that he had never before witnessed such urban wretchedness as he saw in the streets of Mexico City. Publicly, he commended the Spanish for the absence of African slavery in this part of their empire; privately, he told a German friend that he felt as isolated in Mexico as if he had been stranded on the moon. As Echenberg points out, the Mexican historian Vivó Escoto praised Humboldt’s Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain (1811) as “the first modern description of our nation.”

Whereas Echenberg concentrates on a single year, Meinhardt’s book examines the multiple influences on an exceptionally long life (Humboldt died in his ninetieth year, in 1859) that began in the inquiring spirit of the Enlightenment and flourished in the glorious jungle of German Romanticism, epitomized by Novalis’s blue flower, the symbol of Romantic longing for the unattainable. This approach is strikingly different from that of Wulf, for whom Humboldt was the father of environmentalism, seeing nature as a web of life in which all elements are related. Without Humboldt, Wulf has suggested in her introduction to his Selected Writings, Thoreau’s Walden would have been “a very different book.” Thanks to Humboldt’s recognition of the dangerous consequences to the ecosystem of a timber-dependent world, John Muir included forests in his plans for America’s national parks.

Meinhardt, in contrast, while never undervaluing Humboldt’s sense of the natural world, introduces us to a more complex and appealing man than Wulf’s garrulous and faintly tedious naturalist. Meinhardt’s Humboldt is, above all, a product of remarkable times and a life of close connection to an exceptional group of people. Not the least among them was his more conventional but no less extraordinary older brother, Wilhelm.

As her title suggests, Meinhardt’s aim—and achievement—is to show how a thrilling moment in Germany’s intellectual development crucially shaped Humboldt’s approach to life. His surprising decision in 1802 to leave unconquered the final summit of Chimborazo in Ecuador—then considered the highest mountain in the world—is best understood as a “blue flower” moment in keeping with the Romantic fascination with the unattainable. The physical torture that Humboldt inflicted on his own meticulously exposed nerves in the cause of science resembled and seemed even to compete against the torment of unachievable love engendered by the triangular relationships that any German Romantic worthy of the name attempted. Meinhardt raises the fascinating possibility that this strangest of men—an open wound prompted him to rejoice at the opportunity “to dip my finger into the liquid and draw figures and names on my skin”—not only recognized but deliberately exploited the connection between heart and head, body and psyche:

Humboldt’s involvement with Haeften [a young lieutenant whose wedding ball Humboldt officially sponsored while rushing away to raise painful blisters on his own bleeding flesh] was, in a way, not entirely dissimilar: he must have known that he could not fail to get hurt. But here too, perhaps, pain served as a measure. If love caused pain, that at least proved that it really existed. And if the degree of pain was in proportion to the importance of the thing that caused it, then, maybe, trying to avoid it would be beside the point.

“Tedium Towers” was the scornful nickname young Alexander conferred upon Tegel, the castle near Berlin in which he and Wilhelm grew up. The problem was less with the place itself—Goethe, after visiting when Alexander was still a small child, had mentioned Tegel’s supposedly haunted cottage in Faust—than with the fact that the house was governed by their mother, who remains a frustratingly shadowy character in the lives of her two exceptional sons. Marie Elisabeth von Holwede was a wealthy young widow when she married the forty-six-year-old Alexander Georg von Humboldt. The long lease on Tegel came with her. So did a Berlin townhouse and a second country estate that would eventually be sold by Alexander.

Advertisement

Major Humboldt, a charmingly sociable man who had held a position at court, died in 1779, when Alexander was nine and Wilhelm eleven. Their mother had already appointed young Christian Kunth—dutiful, virtuous, and unconscionably dull—as their tutor. Acting as the lonely widow’s loyal steward, Kunth was put in charge of an intensive educational program that Frau von Humboldt financed by taking out a mortgage. Wilhelm rapidly evinced a rare gift for languages. Alexander displayed no such aptitude, expressing only a boyish wish to be a soldier and travel to far-off countries. Wilhelm, not his much-loved younger brother, was the family star.

The first significant change came in the summer of 1787. Shortly before being sent to Frankfurt an der Oder to study cameralism—estate management, then considered a prudent option for slow-witted boys—Alexander joined Wilhelm in regular attendance at two of the most remarkable salons in Berlin. Both of these were run by brilliant Jewish women, the famously beautiful Henriette Herz and her friend Rahel Levin.

Good-looking and possessed of an increasingly inquiring mind, young Alexander enjoyed the quick-witted sparring and sexual openness of these merrily informal salons. (Rahel ran hers in the attic of her parents’ house; Henriette’s was the jollier offshoot of her husband’s all-male gatherings.) Alexander taught Henriette a chic new minuet and learned to joke with her in Hebrew about Tedium Towers. In unexpectedly playful letters, he imagined Henriette and her friend Dorothea Veit grumbling about his lazy ways and awful handwriting (“so small and so crabbed”).

The young Humboldts had stepped into the world of triangular entanglements that they would find replicated several years later when they were keeping company with Friedrich Schiller and Goethe in the bristlingly adventurous atmosphere of the university town of Jena. Dorothea Veit would leave her staid banker husband to live with Friedrich Schlegel, while her dashing fellow salonnière Caroline Michaelis left Schlegel’s brother for Friedrich Schelling. Georg Forster, later Alexander’s close friend and mentor, unhappily shared his marital home in Mainz with Veit’s friend Therese Heyne, along with her lover.

Alexander was thrilled to be introduced to Forster, the botanist on Captain James Cook’s second voyage and one of the younger man’s heroes, by a member of the remarkable group of scholars whom he and Wilhelm met after leaving dreary Frankfurt an der Oder to study at Göttingen, the most progressive German university of its time. It may have been Forster’s example that led Humboldt to contemplate becoming a voyager himself, especially after Forster introduced his friend to Joseph Banks, a man with powerful connections in the worlds of science and travel, during a joint trip to London in 1790.

Meeting Forster and Banks fired Humboldt less with the idea of becoming an explorer than with a longing to escape from the narrow future in the world of Prussia’s public administration that was laid out for him by his mother, who kept a tight grip on the family purse strings and wanted to keep her two boys close to home. Many years later, while recalling in his collected autobiographical writings his youthful desire to travel to faraway countries unvisited by Europeans, Humboldt confessed that he would gladly have sailed “to the remotest South Seas, even if it hadn’t fulfilled any scientific purpose whatsoever.” Meanwhile, encouraged by his mother to try for a highly respected administrative post as an inspector of mines, Humboldt set out to establish his credentials by investigating the mysteries of Unkel, Germany’s most celebrated basalt cave.

The significance of basalt was hotly contested in turn-of-the-century studies of rock formations and the earth’s origins. While the conservative Neptunists saw earth as having emerged from the receding biblical waters, the Plutonists looked at rock formations for evidence of early volcanic activity. Basalt formations like the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland and Fingal’s Cave in the Hebrides—located in water but appearing to be of volcanic origin—were central to the controversy. When Humboldt published his first work, the unappetizingly titled Mineralogical Observations on Some Basalts on the Rhine in 1790, he took care to send an early copy to Abraham Gottlob Werner, a leading geologist and—as it happened—the founder of Germany’s first mining academy.

Nothing separates the early German Romantics more arrestingly from their English counterparts than their passion for mining. Lord Byron, the owner of several mines in Lancashire, once proudly declared that he “never went within ken of a coalpit.” In Germany, a descent into a mine formed an essential part of those serious walking trips relished by all true Romantics.

Far less industrialized than England, early-nineteenth-century Germany associated the underground with hidden knowledge, magic, and self-discovery. But this was no abstract passion. Novalis enrolled in Werner’s mining academy at Freiberg, while Clemens Brentano studied mining in Bonn. Heinrich Heine was drawing on personal experience when he described, in Journey to the Harz, a slow, terrifying descent by muddy and precariously balanced ladders, deep into a foggy, dripping world lit only by flickering lamp.

This was precisely the twenty-one-year-old Humboldt’s experience during his attendance at Werner’s picturesquely situated mining academy. Here, unwittingly, he began the preparation of his body and spirit for the coming years of arduous travel on a largely unknown continent:

Every day, I get up at five in the morning, and, as it takes half an hour to forty-five minutes to get to the mines, I head out straight away. I am busy below ground for five hours…and only this morning have been engaged with drilling and blasting.

Above ground, when not attending Werner’s lectures and writing up his notes, the inexhaustible Humboldt began to devise a new safety lamp. In 1796, by which time he had been offered the job of directing Germany’s substantial holdings of mines in Silesia, Humboldt insisted on personally testing the lamp’s efficacy in a notoriously dangerous oxygen-poor spot, rejoicing only after he had passed out in the process. “When I woke up, I could see the lamp still burning. That was worth fainting for.” Shortly after this achievement, Humboldt decided to reject the directorship but was dissuaded.

Nothing that Humboldt did was ever quite predictable. Back in 1792, the year he first visited Jena and met his brother’s new friend Schiller, Alexander had been given responsibility for three mines in Franconia. “All my wishes…have come true,” he wrote. “I will devote my life wholly to the practice of mining and to mineralogy…. I’m reeling with happiness.” While comfortably established in a former hunting lodge, he managed to discover previously unsuspected seams of coal and funded—out of his own poorly lined pocket—a sturdily practical academy for working miners.

Humboldt was still absorbed in mining when he rejoined his brother at Jena in 1794 and entered Goethe’s circle. Goethe, a contributor to Schiller’s new magazine, Die Horen, was one of the first to notice Humboldt’s growing interest in physics. It was Humboldt’s imaginative account for Die Horen of how chemical elements would react if they were given human form that inspired the central concept of Elective Affinities. Meanwhile, Humboldt (while torturing himself with increasingly hopeless infatuations for young men) began a series of cruel experiments on his own flesh, always in the cause of scientific discovery, that would enable him to measure his resistance to pain. Throughout his travels, both in South America and later during a grueling journey across the Russian steppes, Humboldt would always trust his body to let him know how far he could push himself. It never let him down.

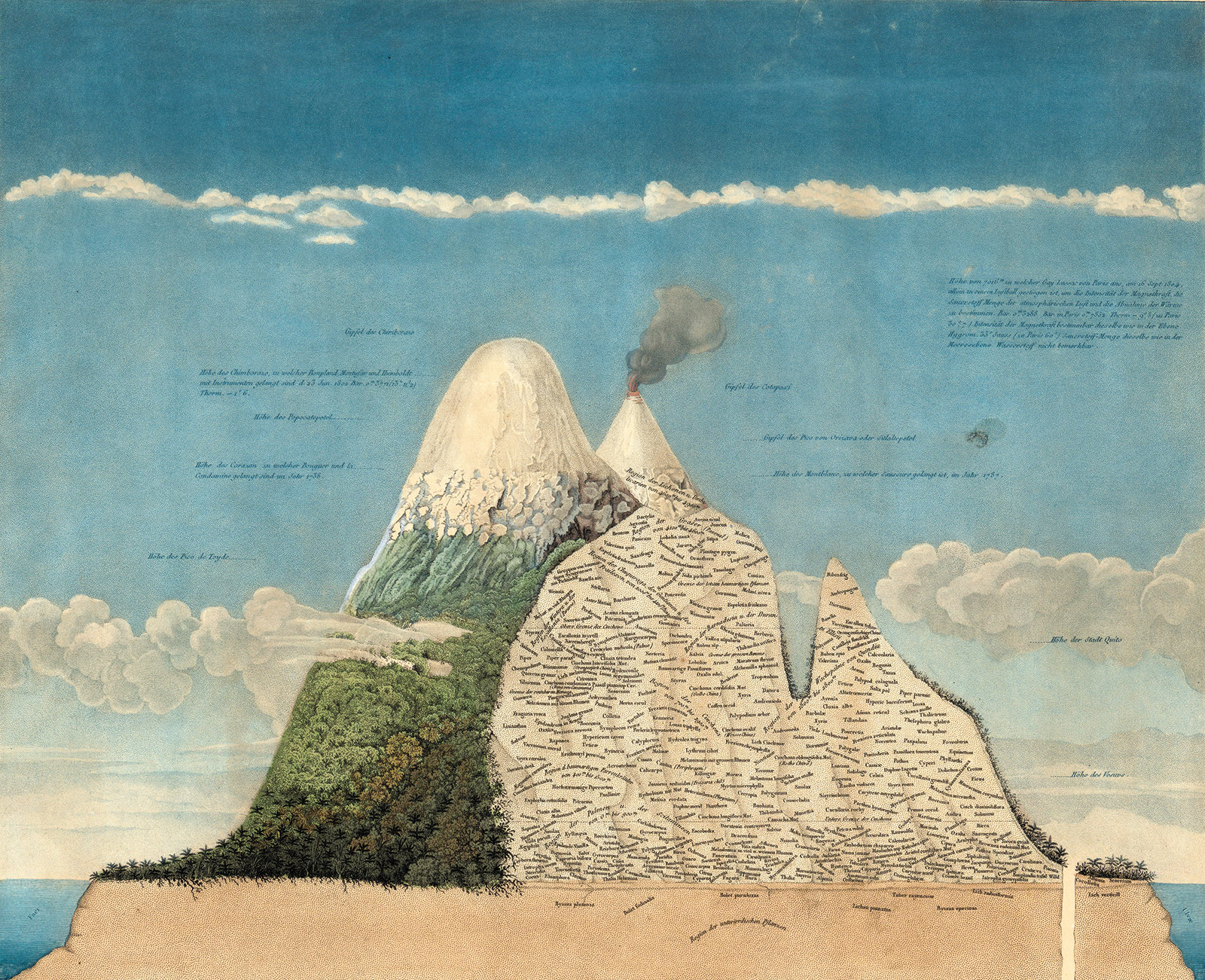

In 1795 Humboldt followed up his reluctant acceptance of the mining directorship in Silesia by taking a short leave of absence. He carried Lieutenant Haeften off for a bachelors’ honeymoon (this took place just before the young soldier finally married the divorced mother of his child), taking his unscientific friend to meet Alessandro Volta at Lake Como. There, by dipping the legs and torsos of neatly skinned frogs into glasses of water, Volta demonstrated what Humboldt had first deduced when his breath had caused a frog’s leg to move: water was an effective conductor of nerve stimuli. Traveling on to the Swiss Alps, Humboldt measured and carefully drew a small area of the mountainside, adding vegetation with indicators of the precise altitude at which each plant could be found. The budding scientist was clearly anticipating the Naturgemälde (1807), his extraordinary chart of Chimborazo. Meinhardt places the Naturgemälde’s underground origins beyond doubt. “I conceived,” Humboldt wrote in 1795, “of the idea to present whole countries in the manner of a mine.” For a mine, depth formed a crucial feature of every chart; the idea of translating this feature into the presentation of a landscape or a mountain, with altitude as the defining variable, was entirely new.

The death of his mother in 1796 changed Humboldt’s life. Not only was he now free to escape from Prussia’s narrow horizons, but Frau von Humboldt’s generous legacy could underwrite the considerable costs of full-scale scientific investigations. One project after another was abandoned because of unexpected obstacles. When Italy was ruled out by Napoleon’s Italian campaigns, Humboldt considered a voyage to the West Indies. After another plan—to go to Egypt—came to nothing, he prepared to join a French expedition to the South Pole. He thought about going to Morocco. Each time, largely due to the extensive military campaigns of Napoleon, his relatively modest ambitions were foiled.

Among the many setbacks, one of the most frustrating had been the last-minute withdrawal of crucial French funding from a voyage led by Nicolas Baudin. Accompanied by another reject from the Baudin voyage, Aimé Bonpland, Humboldt finally gained the blessing of the Spanish king for a project that suited both the traveler and his patron. He was granted permission to go wherever he wished within the vast Spanish territories in the Americas, all in the noble cause of scientific advancement. Humboldt was ecstatic: “Never had a traveller received a more comprehensive permit, never did the Spanish government show greater trust to a stranger.”

Humboldt repaid that trust with an adventure that went far beyond the modest expedition envisaged by his royal master. After penetrating the heart of today’s Venezuela and following the Orinoco River, he set out to explore its connection with the waters of the Amazon system via the Casiquiare canal. A sojourn in Cuba preceded a second journey through Spanish South America, during which Humboldt followed the mountainous peak of the Andes all the way down to Lima, before returning to Europe via Mexico, Cuba, and the United States.

Both Wulf and Meinhardt devote generous space to the encounters that Humboldt himself described with incomparable vivacity. But the Humboldt shown by Meinhardt’s deft selection of quotations has more personality and wit than Wulf’s heroic traveler. Nonchalantly, he praises a tribe of headhunters as “the most cheerful free Indians I have ever seen” and describes the supremely resistible charms of a dish of ant paste. With tongue in cheek, he relates a young cannibal’s guileless account of the particular succulence of the human palm. Exotic landscapes are wittily scaled down to suit the imagination of a European reader. The grassy banks of the Orinoco resemble an English garden, while Venezuela’s deep wooded valleys recall a visit to Derbyshire. Even a moonlight dip, amid small crocodiles, in the Manzanares River reminds a mischievous Humboldt of quiet evenings spent at a European spa town.

The Humboldt who emerges from Meinhardt’s beguiling and beautifully written account is nineteenth-century science’s version of E.M. Forster. Nothing, either in nature or mankind, stood beyond his determination to establish meaningful connections. While Wilhelm employed his linguistic genius to connect languages into globe-spanning patterns, Alexander made a moving and passionate argument for the recognition of all humanity as one united whole. Writing in 1810, he looked forward to the time when “the Caucasian, Mongol, American, Malay, and Negro races will appear less isolated, and we will recognize in this great family of humankind one single organic type, modified by circumstances, which will perhaps remain forever unknown to us.”

A lifelong habit of public discretion ensured that Humboldt himself has remained essentially unknown to us. Despite his eloquent pen and uncommon gift for lecturing, he disclosed almost no personal information about the three decades that followed his disappointing summons back to Berlin from Paris—the heart of scientific activity—in 1827 by Frederick William III. The source of his cheerful tranquility during those last thirty years is hard to discern. True, the hot little rooms on Oranienburger Strasse to which he withdrew in 1842—he shared them with a pet chameleon—were rent-free, thanks to the altruistic purchase of the entire house by the Mendelssohn family, known to the impoverished aging scientist since his early salon-going days. But Paris was Humboldt’s preferred city, and by living to a great age, he had lost many of the old friends, among whom his closest companion had been the mathematician and astronomer François Arago.

The evidence, as Meinhardt acknowledges, is circumstantial, but it appears that the secret of Humboldt’s contentment lay hidden within his walls. In 1827 his servant Johann Seifert married and brought his wife into his master’s house. In 1859—the year of Humboldt’s death—the faithful Seiferts were still in residence. But it seems not to have been simply gratitude that caused Humboldt to stipulate in his will that Johann Seifert “and the many children that were sired in my house” should receive all his material goods, including “gold medals, chronometers and clocks, books, maps.” Humboldt had no fortune to bestow; these were his greatest treasures.

Meinhardt mentions one startling fact that may explain such a curious legacy. On the eve of the marriage of one of Seifert’s daughters to Balduin Möllhausen, Humboldt confided to the groom that both his bride, Caroline, and her younger sister, Agnes, were his own children. Later, he attended the christening of the Möllhausens’ first son—whom the couple named Alexander—in what he strikingly described as “a patriarchal capacity.” In letters to close friends, the Seiferts were always represented as “ma famille.” Most convincingly of all, he insisted that the Seiferts should be granted a burial spot at Tegel.

Whatever their personal relationship to him may have been, the Seifert family provided Humboldt with solace and companionship during the final years of an exceptional life. Writing in Caroline Seifert’s autograph book, Humboldt made a tender request: “Think of me, when I’m gone, with love and cheerfulness.”

This Issue

December 5, 2019

Against Economics

‘I Just Look, and Paint’

Megalo-MoMA

-

*

Knopf, 2015; reviewed in these pages by Nathaniel Rich, October 22, 2015. ↩