Manuscript 286 in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, is a superficially unexciting volume, measuring ten and a half inches tall, eight and a half inches wide, and three inches thick, in an austerely plain modern binding. Produced in Italy toward the end of the sixth century, its 530 pages contain the text of the four New Testament Gospels in Latin, in double columns on tissue-thin sheepskin parchment, its lines spaced out “by clauses and pauses” for reading aloud, in the beautiful, clear “Uncial” script, whose rounded capitals were adopted as the formal handwriting of early Western Christianity. A series of Anglo-Saxon and Latin inscriptions added between the tenth and twelfth centuries record benefactions to St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, establishing that the manuscript was once part of the monastic library there—its final pages retain the rusty imprint of the clasp by which it was chained to its library shelf.

But in the abbey’s tradition, this was no workaday library text but a precious relic, one of the very books brought to England by Saint Augustine of Canterbury, the monk sent by Pope Gregory the Great in AD 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Medieval origin traditions are rarely a safe guide to historical fact, but this one is probably reliable. The text of the Gospels in Ms 286 for the most part follows the Latin translation by Saint Jerome, the so-called Vulgate Bible. But at some crucial points it adopts instead phrasing from an older translation, the Vetus Latina. Both versions were in use in the Papal Palace in late-sixth-century Rome, and while Pope Gregory generally used the Vulgate for his biblical preaching, he too reverted on occasion to the older translation when he believed that it preserved theological insights obscured in the Vulgate. Remarkably, every one of these deviations from the Vulgate text in Ms 286 can be matched in Saint Gregory’s Gospel commentaries, making it overwhelmingly likely that Ms 286 was indeed produced to Gregory’s specifications in the papal scriptorium, and passed from there via Augustine to Canterbury.

Gregory was revered as medieval England’s own apostle—Gregorius noster, or “our Gregory”—and every artifact connected to him was held to be sacred. In Canterbury, books associated with Gregory and Augustine were kept with other holy relics on the high altar. Most of those relics perished when St. Augustine’s Abbey was dissolved in the Reformation. The Augustine Gospel book was among thirty or so volumes rescued—or looted, depending on your point of view—by Matthew Parker, Queen Elizabeth I’s Protestant archbishop, who left it, along with the rest of his magnificent library, to his alma mater, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

Sacred glamour persists around Ms 286: since 1945 it has been carried from Cambridge to Canterbury for the enthronement and swearing-in of each new archbishop. When Pope John Paul II made the historic first papal visit to Canterbury Cathedral in 1982, it was decided that neither pope nor archbishop should sit in the ancient stone chair of Saint Augustine. Instead, Augustine’s Gospel book was solemnly enthroned there for both of them to kiss. There is an entirely credible Cambridge rumor that the librarian who carried the book to Canterbury for that ceremony asserted his robust Protestant credentials by slipping between the pages a copy of number thirty-seven of the Church of England’s Thirty-nine Articles, declaring that “the Bishop of Rome hath no jurisdiction in this realm.” And when in 2005 the Gospel book was displayed in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge as part of an exhibition of manuscripts from Cambridge collections, the museum’s Keeper of Manuscripts encountered a member of the public kneeling in tears before the display case and kissing the ground in veneration.

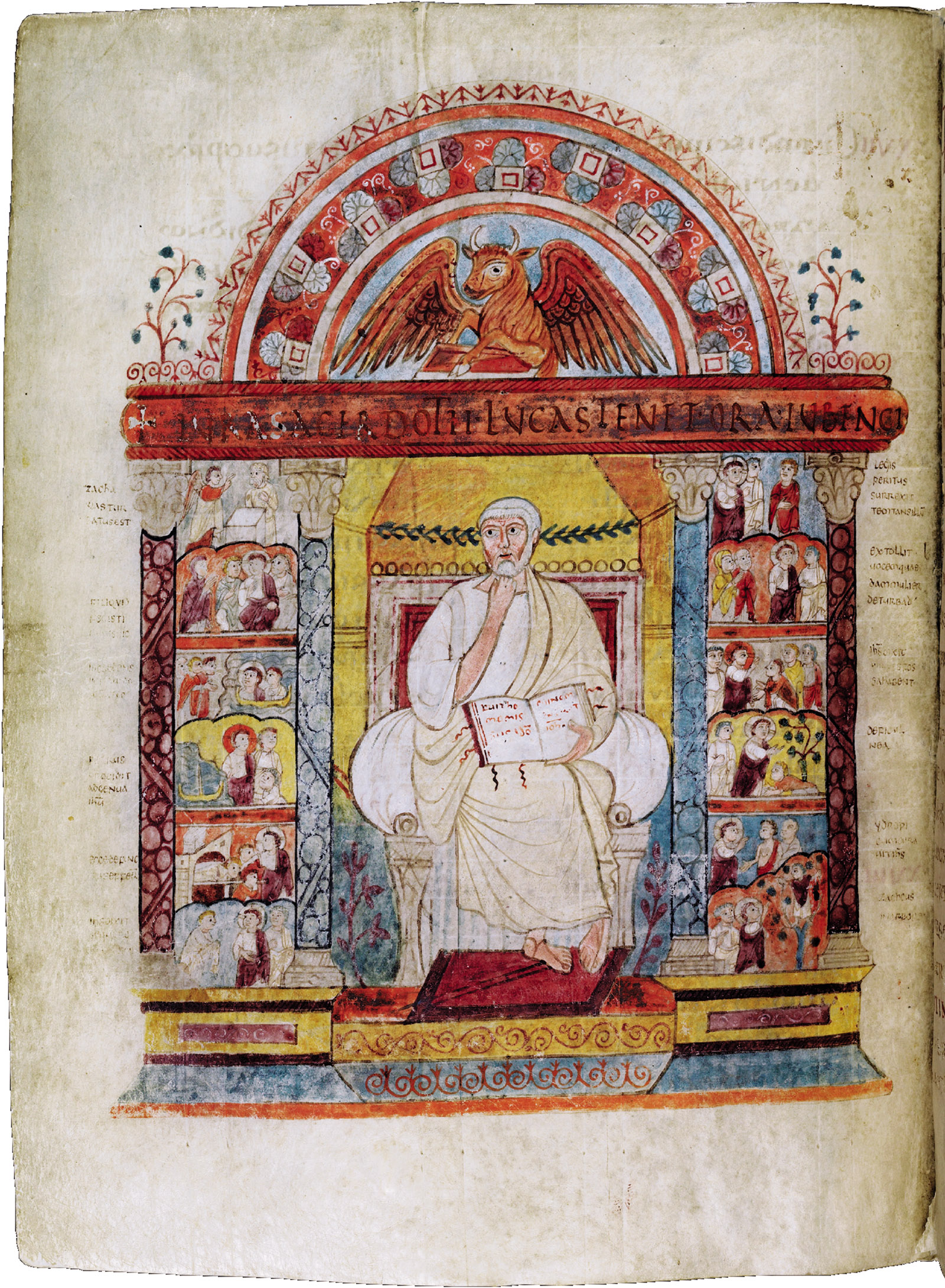

The Augustine Gospel book is one of the twelve “celebrity” manuscripts Christopher de Hamel explores in his delightful Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts; it is perhaps also his favorite. Not only is it “by some margin the oldest surviving illustrated Latin Gospel Book anywhere in the world” and “probably the oldest non-archaeological artefact of any kind to have survived in England,” but he was, till his recent retirement, its privileged custodian as Corpus Christi College’s Parker Librarian. He is fascinated by the book’s antiquity, its Roman origins, the astonishing delicacy of its parchment, and its two surviving illuminations, “stupendous rarities”: a portrait of Saint Luke and a set of charmingly naive scenes from the Passion of Christ. De Hamel is profoundly sensitive to the book’s religious importance. In 2003 he accompanied it to Canterbury for the enthronement of Archbishop Rowan Williams. In his description, as he processed up the cathedral carrying the open book on a velvet cushion, its delicate pages “hummed and fluttered” to the thunderous singing of the 2,500-person congregation, and “it was as if the sixth-century manuscript…had come to life and was taking part in the service.”

Advertisement

De Hamel is an Oxford-trained medievalist who spent most of his career working for Sotheby’s, the international fine arts auctioneers, before returning to academe as Parker Librarian in 2000. For Sotheby’s he handled, cataloged, and helped negotiate the sale of thousands of medieval manuscripts, by his own estimation more than any other person alive. He himself discovered, cataloged, and prepared for sale the last of his chosen manuscripts here, the sumptuous Renaissance prayer book known as the Spinola Hours, entirely unknown “until I unwrapped its parcel in 1975.” The collection of medieval manuscripts is the preserve of the very rich, and the scholarship surrounding it can be both arcane and lofty in tone. Not so with de Hamel. Though he manifestly loves the precious objects he has spent a lifetime studying, he is capable of moral outrage at the wealth “wantonly expended” by medieval kings on their private books “when half of Europe starved.” His encyclopedic learning is carried with an engaging lack of pomposity. The tissue-like pages of the Augustine Gospels curl up like “those paper fish one used to buy in joke shops,” the flashy eighteenth-century red-and-gold endpapers of the glitzy twelfth-century Copenhagen Psalter “always remind me of Christmas crackers,” and a figure of the evangelist Saint Matthew in the Book of Kells resembles “a startled man” peering out above “a great square initial…like a bather caught changing behind a towel on the beach.”

The encounter with each of his chosen manuscripts provides an opportunity for a journey into the medieval world in which it was produced, a meeting with the artisans who prepared the animal skins that form its pages, the scribes who wrote and decorated it, and the patrons—emperors and abbots, kings and queens among them—who paid for it. But de Hamel is almost equally fascinated by the journey of the twelve books through time, the buyers and sometimes piratical dealers who acquired or sold them, the bindings and boxes in which they have been preserved, the libraries in which they have come to rest, the conditions in which they must now be read, the sheer material physicality of manuscripts that no facsimile, however exact, can fully convey. The late, great Leonard Boyle, prefect of the Vatican Library, liked to push precious manuscripts toward his students with the injunction, “Go on, stroke it, it’s an animal.”

So de Hamel is fascinated by the sheer bulk of the Codex Amiatinus, the vast early-eighth-century “pandect,” or single-volume copy, of the Vulgate Bible, its thousand-plus folios made up of 515 calfskins and weighing ninety pounds (“the weight of a fully grown female Great Dane”), resembling nothing so much as “a huge and expensive Italian leather suitcase.” Created in Anglo-Saxon England in Bede’s monastery at Monk Wearmouth, it was one of possibly three copies made from an original bought in Rome from the library of the fifth-century statesman, philosopher, and biblical scholar Cassiodorus. The Codex Amiatinus was chosen as a gift to the shrine of Saint Peter by Bede’s abbot Ceolfrith on his final, uncompleted journey to Rome. When he died en route in France, Ceolfrith’s companions seem to have lugged the vast tome as far as the Tuscan monastery on Monte Amiata, from which it takes its name. There it remained, its origins unrecognized, for more than a millennium, until in 1789 the grand duke of Tuscany deposited it for safe-keeping in turbulent times in the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence, where de Hamel was able to examine it one long afternoon, entirely unsupervised, in the library’s photocopying room.

Scrutiny was similarly relaxed at the National Library in St. Petersburg, where de Hamel went to study the Visconti Semideus, a magnificently illustrated Italian Renaissance treatise on arms and warfare. As he worked through the lunch break in a cozy reading room resembling a school classroom, he noticed that everyone else was using pens rather than the pencils now almost universally required in rare book libraries. The kindly supervisor, noting that de Hamel had missed his lunch, brought him a succession of whisky-flavored chocolates to eat at his desk. De Hamel sat unwrapping and eating them “while turning the pages (carefully) of one of the most perfect and beautiful Italian renaissance manuscripts in existence.”

But few of the custodians he encounters were quite so casually obliging. At the state-of-the-art Morgan Library on Madison Avenue, where he examines a tenth-century Spanish commentary on the Book of Revelation, he notes that readers are not permitted to wear colored nail polish in case it rubs off on the manuscripts. Channeled through a plate-glass double-vestibule with locked doors at either end, “like the keepers’ entrance to the lion enclosure in the zoo,” he is sternly required to wash his hands and silently reproved for attempting to adjust a book-rest without permission. At Trinity College Dublin he is not allowed to turn the pages of the Book of Kells himself, that task being reserved to a hovering librarian.

Advertisement

De Hamel’s distinction as a world authority in his field has deservedly earned him privileged access to many precious treasures, but by his own account he may not always have struck librarians as the ideal reader. In Leiden to examine the Carolingian Aratea, a sumptuous ninth-century illustrated copy of a pre-Christian verse treatise on astronomy, he arrives at the university library dripping from a rain storm, stuffing a sodden woolly hat into his coat pocket and “attempting to look like the kind of person who might be allowed to see the most valuable book in the country” rather than a “bedraggled axe-murderer.”

He particularly detests the increasingly common requirement for readers to wear thin cotton gloves, protecting the manuscript but preventing direct contact with the parchment, from whose texture and thickness much can be deduced about a book’s origins and production. At the Staatsbibliothek in Munich, the mandatory gloves were stylishly trimmed with scarlet, making it look “slightly as though your hands have been cut off.” Readers there are allowed to keep the gloves, and, in a “sad addendum,” de Hamel relates how, despite chafing at the restriction they represented, he decided to keep his pair as a souvenir, soiled as they were with eight centuries of dust from the pages of the Carmina Burana, the notoriously bawdy collection of songs made famous by the composer Carl Orff, only to have his “shocked wife” on his return to England put the disgracefully dirty relics straight into the wash.

Again and again, de Hamel’s book conveys the importance of physical presence to understanding ancient manuscripts. He himself is able to distinguish the “curious warm leathery smell to English parchment” from “the sharper, cooler scent of Italian skins.” As raking sunlight touches for a moment the Leiden Aratea as it lies on the desk before him, he notices something “not visible in any reproduction”: in the bright sunlight it was clear that many of the pictures had been “impressed unnaturally deeply into the parchment pages” with a blunt instrument or stylus, to enable the images to be transferred, via “something like carbon paper,” to pattern sheets for further copies.

He deciphers a vital clue to the medieval ownership of the opulent twelfth-century Copenhagen Psalter, with its glittering, gilded biblical scenes, by “peering for more than an hour at an invisible word on the only unilluminated page in one of the most beautifully illustrated books in the world.” An erased name at the start of a list of relics added to the manuscript suddenly reveals itself to be that of King Valdemar of Denmark, the late-twelfth-century patron who probably commissioned the book. Stitch-holes alongside the psalter’s marvelous illuminated initials provide a surprising window into the distance between the modern and medieval reading experiences. As de Hamel explains, the stitches once anchored textile flaps, miniature curtains designed to conceal the illuminations, which had to be deliberately unveiled by medieval devotees as they turned the pages, a symbolic reenactment of divine revelation itself, and, for the modern reader, “a reminder of what a different world we inhabit.”

As such insights make clear, de Hamel brings warm human sympathy as well as technical expertise to the books he discusses. In one of the most touching moments in the book, he comes across the Latin original of the prayer for “rest and quietness” and “the peace which the world cannot give,” which Thomas Cranmer rendered into stately Tudor prose as the second collect (concluding prayer) at Evensong in the Book of Common Prayer and which is still recited daily in every Anglican cathedral and college chapel. De Hamel comments, “That text has not changed, or the need for peace and freedom from fear, in 850 years. Our world and theirs touch hands for a moment, and the heart leaps in a shared prayer.”

De Hamel, it has to be said, can be less sure-footed in dealing with the technicalities of theology, liturgy, and ecclesiastical law. He reproduces an image of the Norman bishop of Durham, William of Saint-Calais, “tall and stately in a green surplice.” But no surplices are green, and the bishop is actually robed in a chasuble, the sleeveless circular outer vestment worn by priests and bishops when presiding at Mass. He is skeptical about the clerical status of the scribes of some of his manuscripts, even where they depict themselves with the tonsure (shaved head) of a member of the clergy, because at least one such scribe, William de Brailes, is known to have been married. But marriage was not necessarily incompatible with clerical status: in the Middle Ages even the “minor orders” below the level of the sub-diaconate, such as exorcist or acolyte, admitted a man to the ranks (and privileges) of the clerical state, and involved the wearing of the tonsure, but did not impose the obligation of celibacy.

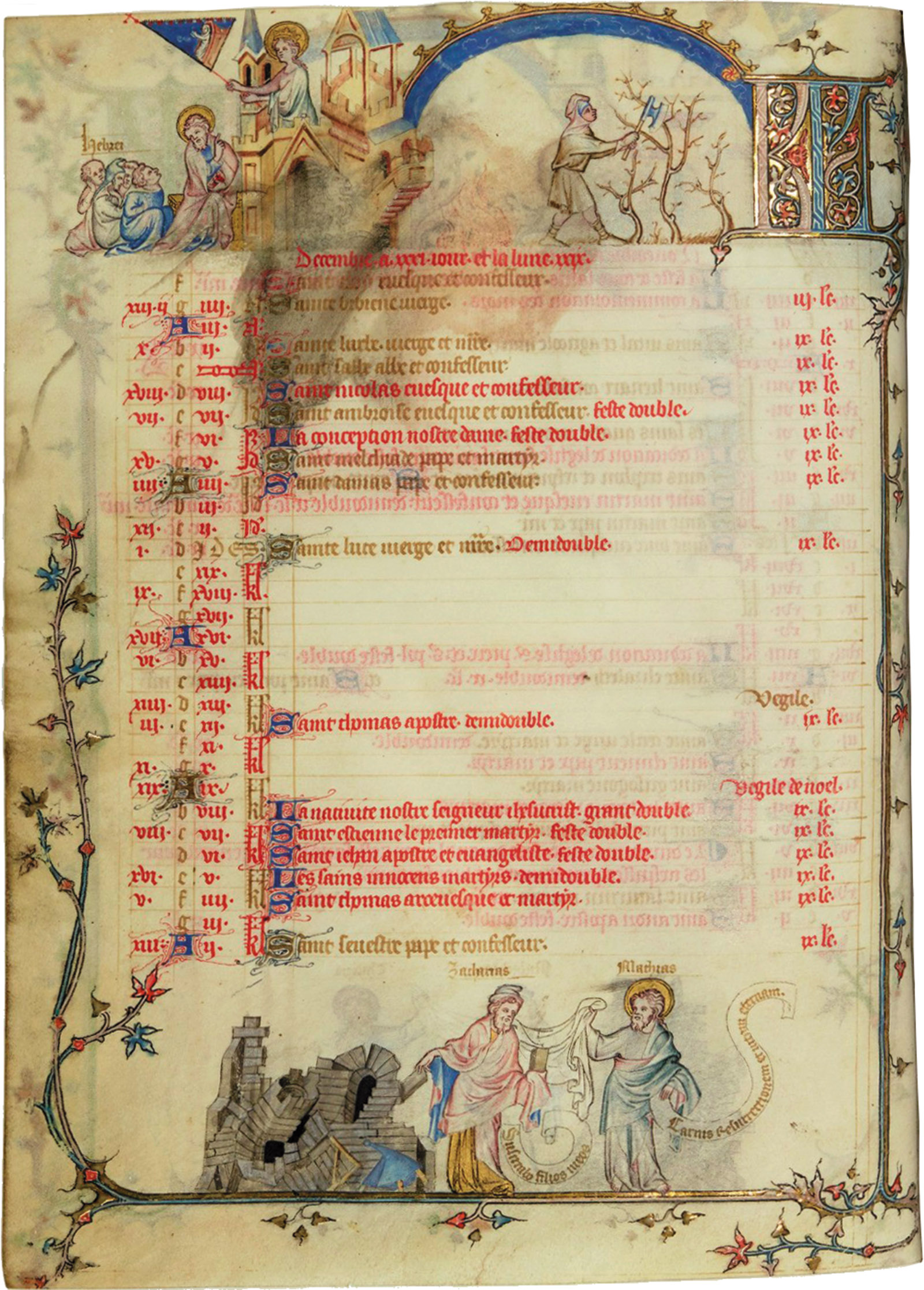

The Hours of Jeanne de Navarre, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, is a lavish fourteenth-century Book of Hours (a liturgical prayer book) made for members of the French royal family. One of its most striking features is the series of drawings at the head and foot of each of the twelve calendar pages with which it begins (see illustration). As de Hamel recognizes, the images at the foot of each page illustrate the supposed contrast between Christian truth and Jewish error. In each one, an Old Testament prophet stands beside a crumbling building, a Synagoga, pulling a brick from the building and handing it on to the named apostle who stands beside him. On banderoles below the prophet and apostle are inscribed one article from the Apostle’s creed and a line from the Old Testament prophecy believed to prefigure it. At the head of each page, a seated apostle addresses a small group of seated listeners and points to the battlements of “a fantastical gothic gateway,” on which a crowned woman stands holding a banner. De Hamel supposes this building to be the gate of heaven, guarded by the Virgin Mary, and the figures of the seated apostle to be repeated representations of Saint Paul, addressing the recipients of the eleven epistles credited to his name in the New Testament.

This is ingenious, but almost certainly mistaken. De Hamel helpfully reproduces two of the calendar pages, and from them it seems clear that the designs at top and bottom in fact form parts of a single interpretive scheme. The crowned woman and the handsome building she stands in front of represent not the Virgin Mary but Ecclesia, Holy Mother Church, presented in deliberate contrast with the collapsing image of Synagoga directly below. Medieval readers would have recognized that the seated apostle is addressing not the Christian recipients of Paul’s epistles but a group of Jews, because on each page one of them wears a tell-tale Jewish cap, and on the upper left of the December page the whole group is helpfully labeled “Hebrei.” The seated apostle points them to Christian truth, represented by the image on Ecclesia’s banner, which, as a magnifying glass reveals, illustrates the article of the creed spelled out on the banderole below.

So, on the page for the month of May, the article of the creed inscribed on the Apostle Philip’s banderole is Christ’s descent into Hell, to liberate the souls of the patriarchs. Accordingly, Ecclesia’s banner depicts the yawning dragon-mouth of hell and the hand of Christ raised in a gesture of authority. The December page depicts the Apostle Matthias, whose article of the creed is “the resurrection of the flesh and life everlasting.” Ecclesia’s banner carries an image of a naked soul rising from the tomb. The pictorial program of the calendar therefore presents a single theological scheme, in which Christianity is understood as having superseded Judaism.

Happily, this is the only instance in which de Hamel’s interpretation seems liable to mislead on a point of substance. His book is the sparkling distillation of a lifetime’s immersion in the world of medieval manuscripts. Since its first appearance in 2016, it has been recognized on all sides for what it is, a masterpiece of accessible and hugely enjoyable scholarship, in which his knowledge of and relish for the beauty and cultural importance of his subject is stamped on every page.

Only one of the twelve manuscripts de Hamel discusses can now be found in the country in which it was produced. The antiquity, rarity, and beauty of these precious objects have always made them liable to cultural annexation, theft, commercial exploitation, or the fortunes of war. Heghnar Watenpaugh’s The Missing Pages follows the fortunes of one such medieval manuscript, displaced by war and the persecution of its custodians, and explores the fraught issues raised by the changing “ownership” of great cultural treasures. The Zeytun Gospels is a thirteenth-century Gospel book in Armenian, of a kind familiar from Latin books we have already discussed, such as the Gospels of Saint Augustine or the Book of Kells. It was the work of a scribe of genius, Toros Roslin, working in the 1250s in the Armenian fortress of Hromkla on the Euphrates, the base for a succession of powerful Armenian warlords and the seat of the catholicos, or head, of the autonomous Armenian Church. But in 1292 Hromkla was overrun and sacked by the Sultan al-Ashraf, and the Gospel book, ransomed with other relics from its Muslim captors, began its journeying. It was eventually enshrined in the Church of the Holy Mother of God in the citadel of Zeytun, in eastern Turkey, where it was credited with supernatural powers and venerated by an increasingly beleaguered Christian minority under Muslim rule.

But during the genocidal attack by the Ottoman regime on its Armenian Christian populations in 1915, the Christians of Zeytun were forced to flee, taking the Gospel book with them. After many vicissitudes, the book is now in the Matenadaran (the Mesrob Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts) in Yerevan, the major repository for medieval Armenian manuscripts. But in the confusion of the genocide, four bifolia, or double pages, containing the magnificently decorated “Canon Tables” (a kind of concordance to the Gospels invented by Eusebius of Caesarea) were removed from the book and taken to the United States by a refugee Armenian family. They then disappeared from view. In 1994 the Canon Tables were bought from a private collector by the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In June 2010 the Western prelacy of the Armenian Church in America, based in California, filed a lawsuit against the Getty Museum for the return of the four bifolia to the Armenian people.

The implications were immense. There were clear parallels with established campaigns to restore Nazi war loot to its rightful owners or their descendants, but the possible ramifications of this case went beyond that. Every great museum in the world holds objects alienated from their original homelands and from owners in legally and morally dubious circumstances: the Parthenon sculptures (the so-called Elgin Marbles), now in the British Museum in London, or the Benin Bronzes, scattered throughout museums all over Europe and America, are cases in point. A judgment in favor of the Armenian Church in this instance might have established a precedent with the potential to empty the world’s museums of some of their greatest treasures. Unsurprisingly perhaps, in 2015 the case was settled out of court: the Armenian Church authorities donated the Zeytun Canon Tables to the Getty in return for an acknowledgment by the Getty of the Church’s right of possession. What else was involved in the settlement is not publicly known.

Chronicling all this, Watenpaugh’s passionate but densely written case study has none of de Hamel’s eloquence, ease, or charm. But her book alerts us to the urgent moral and political questions still to be addressed even in the rarefied world of the museum and the library: she forces us to attend to the human agonies, cultural calamities, and moral ambiguities that lie behind many apparently tranquil museum exhibits.

It is perhaps significant that just one year after the settlement of the Zeytun Gospels issue, the Getty mounted a major exhibition, drawn mainly from its own collections, entitled “Traversing the Globe Through Illuminated Manuscripts.” The exhibition subsequently inspired a collection of essays edited by Bryan C. Keene, Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World Through Illuminated Manuscripts. Both the exhibition and the essays highlighted the transnational character of medieval painted books. The manuscripts ranged widely in both distance and subject matter, from medieval Spanish legal texts to lavishly illustrated editions of the travels of Marco Polo, and from Islamic accounts of the Crusades to Indian lives of the Buddha painted on palm leaves.

Their histories, whether as traded commodities, wartime loot, or objects of diplomatic exchange, defy simplistic attempts to root them in their places of production. And their materials, like the lapis lazuli from Afghanistan that provided the glorious blue in many of the finest medieval European illuminations, or the Egyptian papyrus that lined the covers of the Faddan More Psalter, an eighth-century Irish manuscript rescued from a Tipperary bog in 2006, similarly reveal a medieval world whose borders and horizons were far more open than subsequent national mythologies might allow. In the final essay in Keene’s collection the Getty’s president and CEO, James Cuno, underlines the point by quoting the judgment of a distinguished medievalist, Patrick Geary, that a historiography that emphasizes national identity “has turned our understanding of the past into a toxic waste dump, filled with the poison of ethnic nationalism,” a poison that has “seeped deep into popular consciousness.”

By implication, national claims to the rightful possession of particular cultural treasures—for example, Armenian claims to the Canon Tables—are manifestations of this toxic waste. In contrast to this, Cuno argues that “by presenting representative examples of the world’s artistic legacy, [encyclopedic] art museums encourage an understanding of difference in the world and a shared sense of human history.” They remind us that “the history of the world is inevitably a history of entanglements and networks, of the sharing and overlapping of economic, political, and cultural developments” and “a counternarrative to those…claiming an ethnonationalist link to the remains of cultures found within their sovereign borders.”

The trouble with this formulation is that it empties history of its tragic dimension, and of any moral residue. It would surely look equivocal as a justification for the display in Germany of the looted art treasures of Jewish Europe if, say, the Nazis had won the war. The “sharing and overlapping” of histories look and feel very different, depending on whether the sharing and overlapping is a voluntary exchange or, as in the case of Nazi loot or the alienation of the Zeytun Canon Tables, the consequence of a genocidal attack on an ethnic and religious minority by an imperial power. Cuno doesn’t blink in the face of this line of argument: it is, he writes, “a truth about empire that despite its violence, it has and does contribute to the overlapping of territories and intertwined histories.”

The issues raised in contrasting ways by Watenpaugh and Cuno are far from simple: attempts at any wholesale “repatriation” of every major cultural treasure to its country of origin would be a legal nightmare, and in all probability catastrophic for the conservation, preservation, and public accessibility of many of those objects themselves. There is an obvious sense in which sublimely beautiful cultural artifacts belong to the whole world. But whether museum curators like it or not, many of the world’s great treasures also acquire an ethnic or national identity and significance that is intimately interwoven with their history and cannot simply be dismissed in the name of a transcendent cultural neutrality.

The Book of Kells, for example, is a copy of a Mediterranean text—the Four Gospels—and some of the imagery in its illustrations has affinities with Coptic treatments of the same subjects. In all likelihood it was produced around 800 AD not in Ireland but in an island monastery off the Scottish mainland, and its yellow inks include a pigment, arsenic sulphide, mined from Italian volcanoes. But, as de Hamel shows, the book itself has functioned historically and very specifically as an Irish national treasure, hugely significant both in Reformation-era controversies about the supposed autonomy of the Irish church from Rome, and in nineteenth- and twentieth-century campaigns to establish an Irish national culture distinct from that of England. It has, de Hamel writes, become “probably the most famous and perhaps the most emotively charged medieval book of any kind…the iconic symbol of Irish culture.” It would be a brave museum director indeed who attempted to justify its permanent relocation elsewhere.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Pope John Paul II visited Canterbury in 1979. The pope visited in 1982. The text above has been amended.

This Issue

December 5, 2019

Against Economics

‘I Just Look, and Paint’

Megalo-MoMA