Anyone who watches crime shows knows that twenty-first-century police and prosecutors have at their disposal an array of modern forensic techniques—ways of analyzing hair, fibers, paint, clothing, firearms, bloodstains, and even bitemarks—that can “scientifically” establish guilt or innocence. Or can they? It has become increasingly apparent that most of these techniques are in fact unscientific, involve a great deal of guesswork, and too frequently result in false convictions. Of the more than 2,400 proven false convictions since 1989 recorded by the National Registry of Exonerations, nearly a quarter involved false or misleading forensic evidence.

The precursors of most of the forensic techniques used today were originally developed by police labs as helpful investigative tools, with no claim to being hard science. But starting in the first quarter of the twentieth century, the information obtained by use of these tools was introduced as substantive evidence in criminal cases by lab technicians (or sometimes ordinary police officers) portrayed as highly qualified “forensic experts.” These “experts,” few of whom had extensive scientific training, nonetheless commonly testified that their conclusions had been reached to “a reasonable degree of scientific certainty”—a catchphrase that increasingly became the key to the admissibility of their testimony in court. Such testimony went largely uncontested by defense counsel, who lacked the scientific and technical training to challenge it.

This began to change somewhat in the late 1980s, when DNA testing was developed by scientists applying rigorous standards, independently of the criminal justice system. It proved to be far more reliable in establishing guilt or innocence than any of the forensic techniques that preceded it. DNA testing not only helped to convict the guilty, but also led to the exoneration of hundreds of felons, many of whom had been convicted on the basis of faulty forensic evidence.

The leader in this has been the Innocence Project, founded in 1992 by Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck at Cardozo School of Law. Using DNA testing, the Innocence Project has proved in court that more than 360 people (at last count) who had been convicted of crimes such as murder and rape (and had served an average of fourteen years in prison) were actually innocent. In over 40 percent of these cases, false or misleading forensic science was a major factor in the wrongful convictions. DNA testing, because it was so good, exposed how bad much other forensic evidence was.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court in 1993 gave federal judges the responsibility to act as “gatekeepers” for the admissibility of scientific and other forensic testimony. Previously, both state and federal judges had determined the admissibility of such testimony by applying the so-called Frye test—named after the 1923 decision of the US Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in Frye v. United States. Frye held that to be admissible, an expert’s opinions had to be “deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery…sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.”

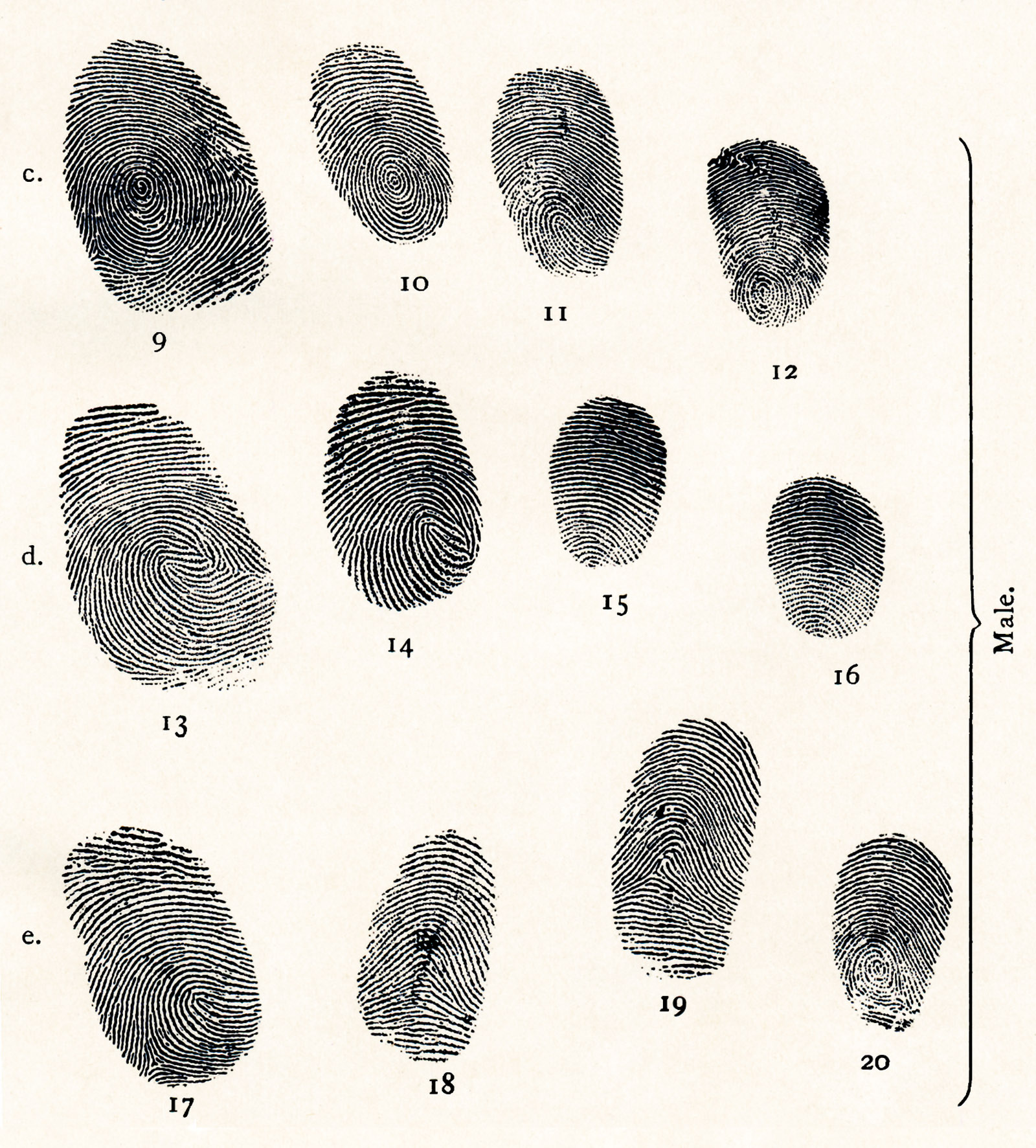

In the Frye case, the court, applying this standard, held that polygraph (“lie detector”) evidence was not sufficiently accepted as reliable to be admissible in federal court, and this remains true today. But in other instances, the “general acceptance” standard proved less stringent. For example, if most fingerprint examiners were of the view that fingerprint comparison was a reliable technique that enabled them to reach results with a reasonable degree of scientific certainty, did this mean that it had “general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs”? Most courts came to answer “yes,” and as a result the Frye standard proved to be little or no impediment to the introduction of most kinds of forensic evidence.

However, in 1993, the Supreme Court, in a civil case, Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., overrode the Frye test. The Court held that federal judges had to take a much more engaged approach to the admissibility of scientific (and other expert) testimony, so as, in effect, to weed out “junk” science. Under this new standard, a judge, in order to rule on the admissibility of purported scientific testimony, had to examine whether the methodology it reflected was not only generally accepted, but also had been subject to scientific testing, had been peer-reviewed in respected scientific journals, and had a known and low error rate. The result was a much more searching inquiry by the “gatekeeper” judge—or so the Court intended.

Initially, this intention was not realized in criminal cases—even though Daubert was so clearly an improvement over Frye that its standards were eventually adopted, in whole or in part, by thirty-eight states. But in these jurisdictions, while Daubert challenges to expert scientific testimony were successful in a notable percentage of civil cases, they almost never succeeded in criminal cases.

Advertisement

One reason for this was money. Most criminal defense counsel lack expertise when it comes to science (as do most judges); to mount a successful Daubert challenge, they need to hire a scientific expert. But most criminal defendants are indigent, and while they are given counsel at state expense, many jurisdictions do not provide additional funding for forensic experts. Furthermore, even in those jurisdictions where it is in principle available, many courts are stingy in their approval of funds for these purposes.

Beyond this, another barrier to the successful challenge of forensic testimony offered by the government in criminal cases is the unconscious bias of judges in favor of admitting such evidence. This may be especially true in state courts, where the great majority of criminal cases are brought. Many, perhaps most, state judges assigned to hear criminal cases are former prosecutors who, in their prior careers, regularly introduced questionable forensic science.

Furthermore, in most states, criminal court judges are elected and cannot afford to be known as “soft on crime” if they want to be reelected. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that some state judges are sensitive to jurors’ expectations that the government will offer the kind of crime lab or “CSI” evidence they have seen on television, and that depriving the prosecution of it may seriously impede its case. When to all these tendencies and pressures there is added the overwhelming fact that in most states the criminal court judges are overloaded with cases and can only with difficulty find the time to undertake a truly probing Daubert hearing, it is hardly surprising that successful challenges to forensic evidence in criminal cases are rare and are often denied on the most cursory grounds.

Nevertheless, the large number of DNA exonerations convinced many thoughtful people that forensic testimony deserved greater scrutiny. In late 2005 Congress directed the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to study the problem. The result was a 352-page report issued in 2009, prepared by a distinguished committee of scientists, academics, and practitioners, and co-chaired by the federal appellate judge Harry T. Edwards, titled Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward.

The report was highly critical of hitherto accepted forensic techniques such as microscopic hair matching, bitemark matching, fiber matching, handwriting comparisons, toolmark analysis, shoeprint and tire track analysis, bloodstain analysis, and much else. Its repeated criticisms were that little or no rigorous scientific testing had been done to determine the validity and reliability of these techniques and that their application was, in practice, highly subjective. Even fingerprint analysis—which until the advent of DNA testing had been considered the “gold standard” in forensic evidence—did not escape criticism. The report noted that it had never been the subject of rigorous independent testing by trained scientists, and the differences and deficiencies in its application by its practitioners often yielded inconsistent results.

In one notorious case, a fingerprint found on a bag of detonators connected to the 2004 train bombings in Madrid was sent by the Spanish authorities to fingerprint databases throughout the world. In response, the FBI announced that its experts had determined that the source of the fingerprint was an Oregon attorney named Brandon Mayfield. Although the Spanish authorities were skeptical, the FBI dispatched one of its experts to Spain to try to change their minds. Meanwhile, the FBI obtained authority to conduct covert twenty-four-hour electronic surveillance of Mayfield. And when, in early May 2004, it somehow imagined that he might flee, it obtained court approval to arrest and detain him. It also obtained warrants to search his home, office, and vehicles.

Two weeks later, however, with Mayfield still in jail (though charged with no crime), the Madrid authorities announced that their own experts had concluded that the fingerprint belonged to a different person, Ouhnane Daoud. Mayfield was released from jail, and the FBI, after several more days of haggling with the Spanish officials, finally admitted that its conclusion that the fingerprint on the detonator definitely matched Mayfield’s was erroneous.

Why did the FBI get it wrong? A subsequent investigation by the Department of Justice’s inspector general found that many factors were involved, including “bias,” “circular reasoning,” and a reluctance to admit errors. But as the NAS report noted, these deficiencies could never have played a part were it not for the fact that “subjectivity is intrinsic” to fingerprint analysis. And where there is a high degree of subjectivity involved in reaching a conclusion, mistakes are inevitable.

The problems the NAS report found with fingerprint analysis were nothing compared to the problems it found with most other forms of forensic science. It concluded:

Advertisement

Much forensic evidence—including, for example, bitemarks and firearm and toolmark identifications—is introduced in criminal trials without any meaningful scientific validation, determination of error rates, or reliability testing to explain the limits of the discipline.

The main recommendation of the report was the creation of an independent National Institute of Forensic Science to rigorously test the various methodologies and set standards for their application. Although, in my view, this would have been an ideal solution, it was opposed by a variety of special interests, ranging from the Department of Justice to local police organizations and private forensic labs. Nevertheless, in response to embarrassments like the Mayfield incident as well as continuing expressions of concern from Congress, the Department of Justice—in collaboration with the Department of Commerce (which oversees what used to be called the Bureau of Standards and is now called the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST)—agreed in 2013 to create a National Commission on Forensic Science to recommend improvements in the handling of forensic evidence.

The commission’s thirty-one members represented virtually every interest group concerned with forensic science, including prosecutors, defense counsel, scientists, forensic science practitioners, lab directors, law professors, and state court judges. (There was also, ex officio, one federal judge—me.) The idea was to reach consensus among all the relevant participants wherever possible. To this end, the commission required that two thirds of its members had to vote in favor of a recommendation in order to send it to the government.

Over the four years of its existence, from 2013 to 2017, the commission made more than forty recommendations to the Department of Justice, which accepted most, though not all, of them. For example, over 80 percent of the commissioners approved a resolution that forensic experts should no longer testify that their opinions were given with “a reasonable degree of scientific [or other forensic discipline] certainty,” because “such terms have no scientific meaning and may mislead factfinders” (that is, jurors and judges) into thinking the forensic evidence is much stronger and more scientific than it actually is. But although the Department of Justice accepted that recommendation, and thus made it binding on forensic experts called by federal prosecutors, many states still permit this highly misleading formulation, and some even require it before allowing a forensic expert to testify.

As this illustrates, the commission’s work did not have as much effect on the states as its members had hoped it would. Some states either ignored or expressed disagreement with its recommendations even when they were adopted on the federal level by the Department of Justice. Many police-sponsored forensic laboratories, in particular, viewed much of the commission’s work as an attack on their integrity rather than an effort to improve their methodology. Its recommendations received the most positive response in places where forensic lab scandals had made communities open to change. For example, in Houston, a series of shoddy and even dishonest practices by the police crime lab had been exposed. These culminated in 2014 when one of the lab’s DNA technicians, who had worked on 185 criminal cases, including fifty-one murders, was found not only to have used improper procedures, but also to have fabricated results and falsely tampered with official records—all seemingly to help convict defendants the police were “sure” were guilty. In response, the city created a new forensic lab, the Houston Forensic Science Center, entirely independent of the police and widely regarded as a model for the future, but still very much the exception to forensic labs in most municipalities.

The commission faced still another difficulty. The broad spectrum of interests represented in it, and the requirement that it proceed by something close to consensus, meant that it could not easily address the two fundamental problems with most forensic science identified by the NAS report: the lack of rigorous testing and the concomitant presence of a significant degree of subjectivity in reaching results. The commission was attempting to begin addressing these problems—in particular the issue of error rate—when its term expired in April 2017. Although a majority of the commissioners asked that its term be renewed so that these questions could be addressed, the new Trump administration’s Department of Justice flatly rejected the idea, claiming that it could proceed better through internally generated improvements.

In the view of many observers, the record so far invites skepticism about this claim. The first official product of the department’s internal Forensic Science Research and Development Working Group, issued in November 2018, was a set of new uniform terms for forensic testimony and reporting by federal forensic experts. Although many members of the commission and others had urged that experts avoid making categorical statements such as “the markings on the bullet found at the scene of the crime and the markings on the inside of the barrel of the gun found in the defendant’s apartment came from the same source”—as opposed to more nuanced statements reflecting probabilities, error rates, and subjective choices—the department imposed on its experts the categorical approach. In the words of Simon A. Cole, a professor of criminology, law, and society at the University of California at Irvine who has closely monitored the department’s policies, its new standard is “neither logical, nor scientific,” and suggests that the department is “reversing progress toward improving forensic science in the US.”*

The obvious reason why the department opted for the categorical approach is that it is more effective with juries. This illustrates the heart of the problem of leaving forensic science improvements to police and prosecutors. However much they might sincerely wish to improve forensic science, they are subject to the kinds of biases that bedevil good science.

There is one earlier development worth mentioning. Shortly before the end of the Obama administration, in September 2016, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), a group of the nation’s leading scientists that, since 2001, has advised the White House on scientific matters, issued a report entitled Forensic Science in Criminal Courts: Ensuring Scientific Validity of Feature-Comparison Methods.

The report began by surveying the data that showed just how weak much forensic science is, even by the government’s standards. A good example is microscopic hair analysis, by which an expert claims to determine whether human hairs found at the scene of a crime uniquely match the hair of the accused. According to the report:

Starting in 2012, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and FBI undertook an unprecedented review of testimony in more than 3,000 criminal cases involving microscopic hair analysis. Their initial results, released in 2015, showed that FBI examiners had provided scientifically invalid testimony in more than 95 percent of cases where that testimony was used to inculpate a defendant at trial.

How could this be? A recent example illustrates what can happen. In a decision handed down on March 1 of this year, the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit reversed the 1972 murder and rape conviction of John Milton Ausby, describing in some detail how, at his trial, an FBI agent purporting to be a “microscopic hair analysis specialist” testified that hairs exhibit characteristics “unique to a particular individual,” and that the hairs found on the victim’s body and in her apartment were “microscopically identical” to Ausby’s hair. But, stated the court, “the government now concedes that the testimony of the forensic expert was false and misleading and that the government knew or should have known so at the time of Ausby’s trial.” In other words, the agent effectively lied, and the government knowingly or negligently allowed him to do so. While the FBI must be given credit for its subsequent review of these egregious errors, that did not happen until 2012, forty years after Ausby’s conviction. And even though it admitted these errors, the Department of Justice judged them to be immaterial and opposed Ausby’s release. His conviction was not actually vacated until 2019, by which time he had served forty-seven years in prison.

Overall, the PCAST report concluded, as had the NAS report, that most forensic science suffers from a lack of rigorous testing and an excess of subjectivity that makes it unreliable. Since, however, Congress had not pursued the NAS report’s recommendation that an independent federal forensic institute be established, the PCAST report suggested that the NIST undertake scientific studies “to assess the foundational validity of current and newly developed forensic feature-comparison technologies.” The NIST was thought to be the next best option because it had much less of a stake in the outcome of such studies than the Department of Justice, let alone state and private labs.

The PCAST report was met with severe criticism, notably from the FBI and local police authorities, who were loath to admit that the forensic science they used all the time was as fundamentally suspect as the report found. More importantly, the change in administration meant that the report and its recommendations were largely shelved, although the NIST has continued to do some helpful work on narrower issues.

One possible exception to the lack of progress may yet come from the federal judiciary. The PCAST report was critical—in my view, correctly—of the failure of most federal judges to undertake meaningful review of the admissibility of forensic science, notwithstanding that Daubert effectively mandates that they do so. The PCAST report therefore suggested that the overall federal judiciary, through its own advisory committees and educational arms, encourage federal judges to be more involved in such cases and provide guidance to these judges. The recommendations relating to forensic science are currently being considered by the relevant committees of the federal judiciary. In particular, these committees are focusing on whether to require federal prosecutors to disclose to defense counsel well in advance of trial not only the government’s forensic experts’ opinions but also what data and methods its experts relied upon in reaching their opinions.

Separately, there are steps that could be taken now to improve forensic science without undue expense.

First, forensic labs could be made more independent of police and prosecutors’ offices. Instead of being viewed as partners of the police and prosecutors, they could develop an ethos of objectivity and independence.

Second, all forensic science labs, including private ones, could be made subject to state and federal accreditation requirements. An ethics code for forensic experts, already drafted by the Nation Commission on Forensic Science and partly accepted by the Department of Justice, could also be made binding and enforceable on all such labs.

Third, testing by forensic labs could be made “blind,” that is, free from any biasing information supplied by the police or other investigating authorities.

Fourth, the courts could make greater use of court-appointed, comparatively neutral experts in place of the less-than-neutral experts chosen by the interested parties. Federal law already allows federal courts to appoint such experts, but the judges very rarely have done so.

Fifth, courts could reduce the judge-made barriers to collateral (post-appeal) review of criminal convictions in which doubtful forensic testimony played a part. For example, many states deny defendants the right to argue that their convictions were the result of deficient forensic testimony if they did not challenge these deficiencies at trial—even though the deficiencies may have only become known many years later. By contrast, courts in Texas, in response to some of the scandals mentioned earlier, now allow such challenges.

None of these steps would approach in significance the more far-reaching proposal made by the NAS report: the creation of an independent National Institute of Forensic Science to do the basic testing and promulgate the basic standards that would make forensic science much more genuinely scientific. But as noted above, there are a variety of special interests opposed to such an institute, and until public opinion forces their hand, the more modest steps outlined above may be the best we can do.

Meanwhile, forensic techniques that in their origins were simply viewed as aids to police investigations have taken on an importance in the criminal justice system that they frequently cannot support. Their results are portrayed to judges, juries, prosecutors, and defense counsel as possessing a degree of validity and reliability that they simply do not have. Maybe crime shows can live with such lies, but our criminal justice system should not.

This Issue

December 19, 2019

No More Nice Dems

What Were Dinosaurs For?

The Master’s Master

-

*

Simon A. Cole, “Forensics, Justice, and the Case for Science-Based Decision Making,” blog of the Union of Concerned Scientists, November 14, 2018. ↩