I am looking at a little book called Spanish for Your Mexican Visit, published in Mexico in 1935 and bound in rough cloth with the title and some drawings stamped on the cover in red. Inside, amid the lessons on everything from figuring out the trains to navigating antique shops and attending cabarets and bullfights, there are advertisements, many with comic illustrations, for the best places to find homestyle cooking or buy postcards of Diego Rivera’s murals. The author, Frances Toor, was an American who moved to Mexico in 1922 and published guidebooks and a magazine, Mexican Folkways, which celebrated the art and culture of the country. Toor’s audience was Americans who believed that the United States had long ago lost its pioneer spirit. They were hankering for a country that seemed raw, complex, and impassioned.

From Toor’s day down to our own, Americans, especially those with bohemian interests or at least bohemian yearnings, have been fascinated by life south of the Rio Grande, where periods of leftist political hope have intersected with vital popular arts traditions and storied pre-Columbian civilizations. The Museum of Modern Art mounted a show of Diego Rivera’s work in 1931 and, nine years later, an immense survey entitled “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art.” Since then, that sense of Mexico as a kind of Ur-America—more intense, more open, more dramatic than the US—has surged and ebbed but never really gone away. Frida Kahlo, who had a stormy marriage with Rivera, has by now probably eclipsed him in the public imagination; her finest paintings, whatever they owe to the psychological experiments of her friends among the European Surrealists, cast a mythopoetic spell that owes much to pictorial storytelling as practiced in Mexico since ancient times.

Kahlo’s skyrocketing reputation is only one aspect of a larger movement. Shifting demographics have given Latin American culture an ever-expanding part in the culture of the US, and museums are responding with exhibitions that aim to discover or at least explore how we arrived here. Two years ago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art mounted “Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985.” This winter, the Whitney Museum of American Art is presenting “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945.”

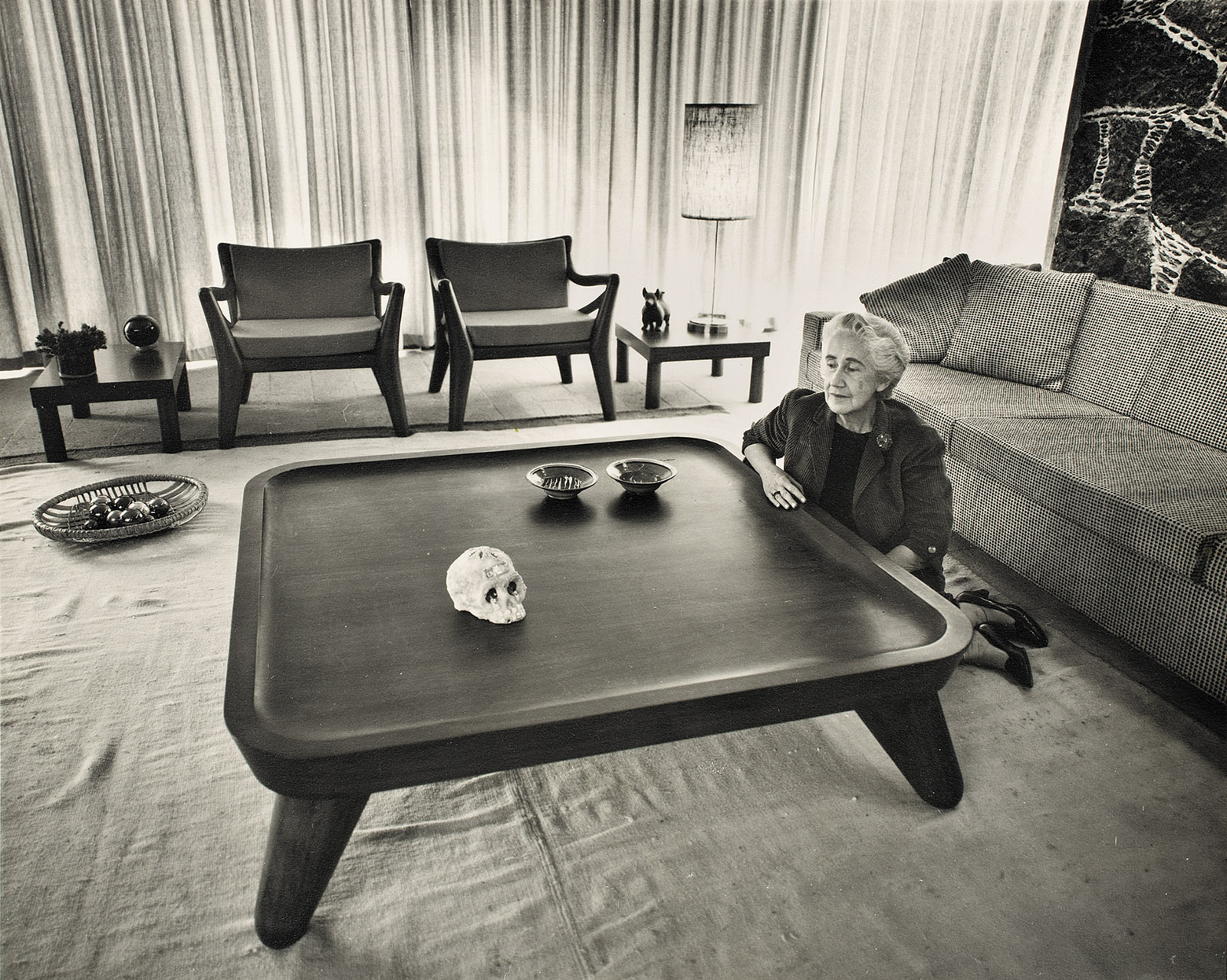

The revelations, collaborations, and confusions that animated artists and art lovers in Mexico and the United States in the twentieth century are all on display at the Art Institute of Chicago in an elegant design show with a mysterious title: “In a Cloud, in a Wall, in a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury.” That poetic flourish comes from an observation by the central figure in the exhibition, the furniture designer Clara Porset, who believed that “there is design in everything”—whether manmade objects such as a pot and a chair or natural phenomena such as the sea, sand, and clouds. The show gathers together work by six women, three of them from the US, who lived in or visited Mexico in the midcentury years. In addition to chairs and other furnishings by Porset, there are photographs by Lola Álvarez Bravo, rugs by Cynthia Sargent, hanging metal sculptures by Ruth Asawa, and textiles by Anni Albers and Sheila Hicks. It’s all pulled together with a beguilingly informal installation that features lots of pale wood for display cases and portable walls.

Mexico is very much the protagonist of the exhibition. But at times the Mexico that emerges is more phantasm than reality. That isn’t surprising, because artists who crossed the border, whether headed north or south, were inevitably in search of something that was as much in the mind’s eye as in the actualities that filled their eyes. Cosmopolitan Mexicans like Kahlo and Rivera (he had lived and worked in Paris) approached indigenous Mexican traditions with an insider’s proprietary feeling and an outsider’s freedom to pick and choose.

For Anni Albers and her husband, Josef Albers, émigrés to the US from Hitler’s Germany, the art and architecture of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were astounding achievements. They discovered forms and symbols that they believed prefigured the radical modern visual experiments to which they had dedicated themselves at the Bauhaus and for which they were now advocating in the US, first at Black Mountain College and later through Josef’s pedagogy at Yale. They made a total of thirteen trips to Mexico over a period of four decades and were thrilled by the continuing vigor of Mexican crafts, at a time when handmade objects seemed to be disappearing in the US and Europe. Creative spirits saw Mexico as a country with strong artistic traditions, whether ancient or modern, that new generations could embrace, reshape, and transform. Hicks studied traditional weaving techniques, which she almost immediately proceeded to rework with a sensibility attuned to the expressive effusions and astringencies of modern painting.

Advertisement

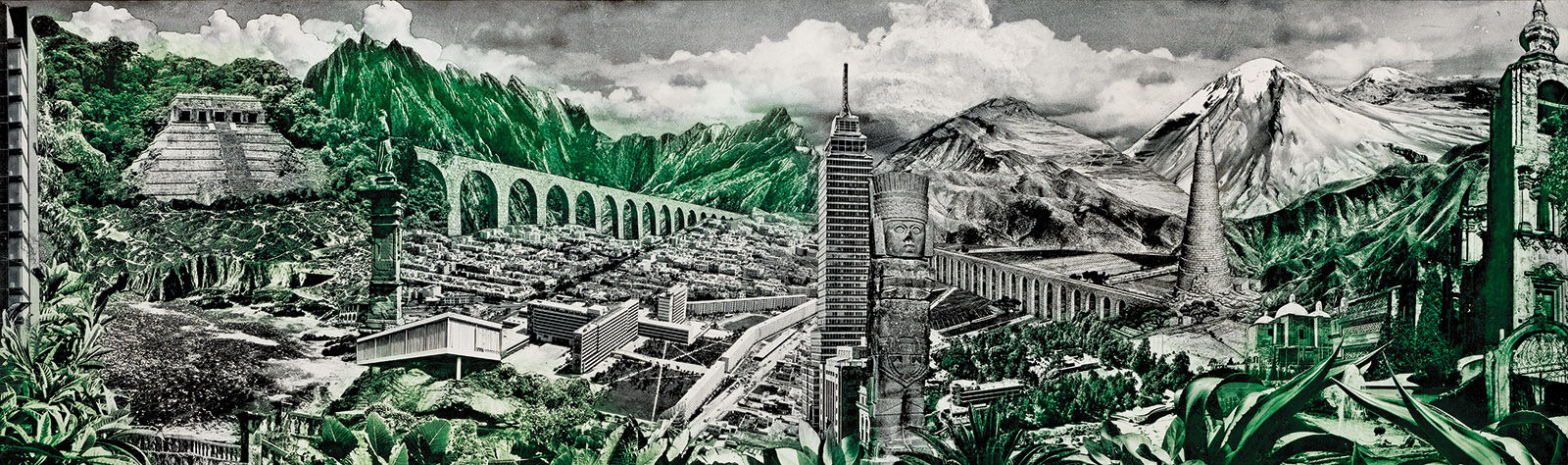

Zoë Ryan, the curator of “In a Cloud,” treads carefully as she navigates what might turn into an ideological minefield, with six women juggling the competing interests of indigenous arts-and-crafts traditions and international modernism, in a country where social justice and economic development sometimes seemed to be at loggerheads. Lola Álvarez Bravo cut and reassembled her photographs into montages that gave a shot of hyperbolic drama to the ambitious plans for social and economic transformation that animated Mexico at midcentury. She pulled together dozens of images of men building railroads, highways, and automobiles in jagged, exuberant panoramic compositions. In one, entitled Architectural Anarchy in Mexico City, she gave the capital’s juxtapositions of ancient temples and modern skyscrapers a discombobulating energy that brings to mind the dreams of Hieronymus Bosch. Álvarez Bravo’s visual rhythms are rousing, stentorian—the optical equivalent of a stadium full of citizens singing patriotic songs.

Cynthia Sargent and her husband, Wendell Riggs, who established a successful business in Mexico City marketing elegant rugs, suggest another side of the economic dynamics of the Mexican experiment. They might be especially vulnerable to accusations that they were engaged in a sort of cultural voyeurism as she rejiggered traditional colors and patterns to suit the appetites of a sophisticated clientele. As for Clara Porset, when she based a modern armchair on an ancient Totonac sculpture of a seated figure (see illustration below), she was engaging with the Mexican past as a romantic archaeologist, resurrecting buried forms in much the way that neoclassical designers in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe had revived Roman originals. In certain instances, the imaginative transformations that characterize the work on display give way to something closer to sentimentalization.

Ryan’s exhibition raises some big and difficult questions. Did women, who historically had a particularly close relationship with the decorative and utilitarian arts, have a privileged place in the reimagining of art in the twentieth century? Did they have unique strengths to contribute to the modernist moment, at a time when an art grounded in rhythms and patterns that many regarded as decorative was beginning to eclipse the narrative and representational impulses that had dominated art for the preceding five hundred years, at least in Europe? And what do we think about artists trained in Western European or American schools who use techniques and styles evolved by anonymous third-world craftspeople?

Ryan sees Porset as the figure who can begin to provide some answers to these questions. Porset, who was born in Cuba in 1895, was forced to move to Mexico in 1935 when her left-wing affiliations put her in the crosshairs of the Cuban government. In 1938 she married Xavier Guerrero, a painter and a member of the Mexican Communist Party whose artistic and political sensibilities meshed with her own. Ryan begins with an examination of “Art in Daily Life: Well-Designed Objects Made in Mexico,” an exhibition that Porset mounted in Mexico City in 1952. What especially interests Ryan is that among the more than one hundred objects Porset included were utilitarian objects made by hand and others made by machine. Ryan feels that Porset made a dramatic break with the exhibitions of beautifully designed utilitarian products that had been promoted in the United States, especially at MoMA, in which handmade objects were almost invariably dismissed as not commercially viable. Porset, who argued that “forms that are made by hand and those that are made by machine have similar requirements,” was taking the view that in a developing country like Mexico, where industrial practices had not yet eclipsed artisanal ones, a bowl made by hand and a bowl made by machine might live together. They might both be beautiful, and even beautiful in similar ways. “During this time of technological transformation,” Porset wrote, “it is important to infuse industry—that is, the machine—with the extraordinary sensitivity of the Mexican, who over the millennia, has created so many and such a variety of beautiful forms using manual techniques.”

However humble many of the items that Porset gathered together may have been, there was something splendidly idealistic about the impulses that animated “Art in Daily Life.” The yearning to see old forms and new forms as essentially reconcilable, even at a time when many Mexicans were hoping for dramatic cultural, social, and political change, had deep roots in the modernist movement—and, deeper still, in a Kantian or Platonic feeling for ideal or ultimate forms. In the 1930s, as the Bauhaus was shuttered by the Nazis, Porset had been in contact with Josef and Anni Albers and other important figures at the school; she was among those who spread the Bauhaus’s gospel of the unity of art and design and of the artisanal and the industrial in the New World.

Advertisement

But like almost everybody who embraced those principles, she found them difficult to put into practice. Porset wanted to design for Mexicans what she called “our own kind of furniture,” reimagining traditional forms, especially the butaque, a chair with a sloping back. Her butaque chairs, produced in a number of versions, with a gracefully curving wooden frame combined with leather or woven wicker or jute, are wonderfully suave, at once luxurious and austere. But Porset found it well-nigh impossible to expand into the mass market; the clientele for her innovative furniture remained sophisticated and well-to-do. Her chairs, succinctly designed to suggest seating’s primal state, looked wonderful in the bold, clean-lined interiors conceived by the great Mexican architect Luis Barragán, who knew how to give quotidian spaces an Olympian grandeur.

Porset was neither the first nor the last twentieth-century designer to find that her work made little headway among the public at large. Alvar Aalto and Charles and Ray Eames faced some of the same challenges with their brilliant furniture designs, which were, if not a minority taste, then certainly not a majority one. Porset was deeply disappointed in the 1950s when she designed a line of low-cost, durable furnishings that were meant to be marketed to government employees who were moving into a new housing project in Mexico City. She hoped that the furniture, with its “regional Mexican character,” would strike a chord. But apparently there were few people who cared to acquire it. She complained that neither the government nor the manufacturer had done all it could to encourage buyers. Porset couldn’t help feeling that an opportunity had been lost to educate taste by linking new production methods with wooden forms that had an old-fashioned, plainspoken, back-to-basics beauty. Having aimed to celebrate the popular arts, she found herself at certain points fed up with popular taste.

The act of creation remains enigmatic, whether the creator has been trained in an art academy in a world capital or has learned through an apprenticeship in a tiny provincial village. Porset embraced an idea, which went back at least as far as Ruskin and the Arts and Crafts Movement in nineteenth-century England, that the imagination of the anonymous artisan might be every bit as refined as (maybe more refined than) that of the eminent academician. There was likewise a hope that this egalitarian spirit would animate consumers as well as creators. Porset wanted her fellow Mexicans, regardless of their socioeconomic situation and educational and cultural opportunities, to respond to designs, both old and new, with a fresh, open eye. But if Ryan’s exhibition demonstrates anything, it is that whatever egalitarian dreams might have animated its initial conception, all imaginations are not equal.

Sheila Hicks—who had studied at Yale with Josef Albers and George Kubler, a scholar of pre-Columbian art who wrote a celebrated book, The Shape of Time—was in her twenties when she lived in Mexico and began to immerse herself in various ways of weaving. She didn’t seem to regard what she had learned at an Ivy League university as any more or less significant than what she learned about knotting methods from Rufino Reyes, a weaver in Mitla, Oaxaca. The scintillating colors and dazzling patterns that she encountered in Mexico have remained with her throughout a long career. But she has never felt any compunction about challenging the artisanal traditions that she so evidently admires. Hicks made that perfectly clear around 1960, when she gave a large textile piece the rather ironic title Learning to Weave in Taxco, Mexico. This big, brilliant work, with its concentrations and cascades of red and orange threads, opposes tight traditional weaving to areas where the warp threads, wrapped in bundles, create utterly untraditional passages of long, lacy fringe. “Any good weaver,” Hicks announced, “would look at this and say, I don’t think this lady knows how to weave.” Mexico provided her the opportunity to learn certain things and then go right ahead and unlearn them.

Hicks built the beginnings of a career in Mexico City with help from influential figures in the world of art, architecture, and design. When her weavings were shown there in 1961, she hung them on the wall so that they would be considered like paintings. A critic wrote that “the old prejudice regarding applied arts has lost its meaning.” There is, of course, a paradox here, for if the only way to lose “the old prejudice” was to present a weaving as if it were a painting, didn’t that only reinforce the old prejudice? Hicks’s smaller textiles, with their irregular shapes and eruptions of variegated colored and textured threads, are almost anti-textiles—swaggering, often wonderfully engaging Dadaist deconstructions of a tradition.

In the 1970s, when Hicks was commissioned to create a considerable number of works for the Camino Real Hotel in Cancún, she dreamed up some monumental bundles and ropes of hot red, orange, and purple yarns, which were provocatively displayed in its public rooms, some from the ceiling, others along a wall; they are closer to soft sculptures than to textiles. The work is romantically exotic; these are Mexican souvenirs on steroids. “I never lost touch with Mexico,” Hicks, who moved to Paris in 1964, observed in 2018. “I’ve always been emotionally and artistically active there.” But even as she was saluting the old styles, there’s a sense in which she was bidding them farewell. Her encounters with Mexican art and culture mingle reverence and revolt in ways that bring the Abstract Expressionists to mind.

Of all the artists in “In a Cloud” whom we see responding to Mexican art and culture, Anni Albers is the one who really digs into the traditions she found there and in South America. Albers, a generation older than Hicks, inspired the younger artist, who said that some of the small textiles that Albers referred to as “pictorial weavings” proved to her that a weaving didn’t need “to be utilitarian. It seemed to me she was giving meaning and expression to this soft, pliable material.” Albers, who had begun weaving at the Bauhaus, discovered in the textile traditions of the Americas, which she studied closely, an ancient discipline that energized a modern imagination. To weave was to think, to feel, to know.

On Weaving, the book Albers published in 1965, can on first glance look like a rather dry treatise. She keeps her language matter-of-fact. The various forms of weaving are presented in a series of cool, crisp diagrams. But central to Albers’s greatness is the punctiliousness with which she investigates each aspect of the weaver’s art. She rejects the idea that “a limitation must mean frustration,” and thus she establishes a profoundly intimate alliance with the artisanal traditions, in which limitations were enthusiastically embraced. “To my mind,” Albers continues,

limitations may act as directives and may be as suggestive as were both the material itself and anticipated performance. Great freedom can be a hindrance because of the bewildering choices it leaves to us, while limitations, when approached open-mindedly, can spur the imagination to make the best use of them and possibly even to overcome them.

Albers didn’t see the Mexican and Central and South American works that she admired as jumping-off points but as opportunities for total immersion. She didn’t recoil from the discipline that craftspeople had apparently accepted as a matter of course. In a long and varied career, she designed for industry and produced limited-edition graphics; the Chicago show includes some of the printed cotton textiles she made for Knoll, which are still in production. While this is highly sophisticated work, it is in her small, one-off textiles that Albers dissolved every distinction anybody cared to make between the art and design traditions.

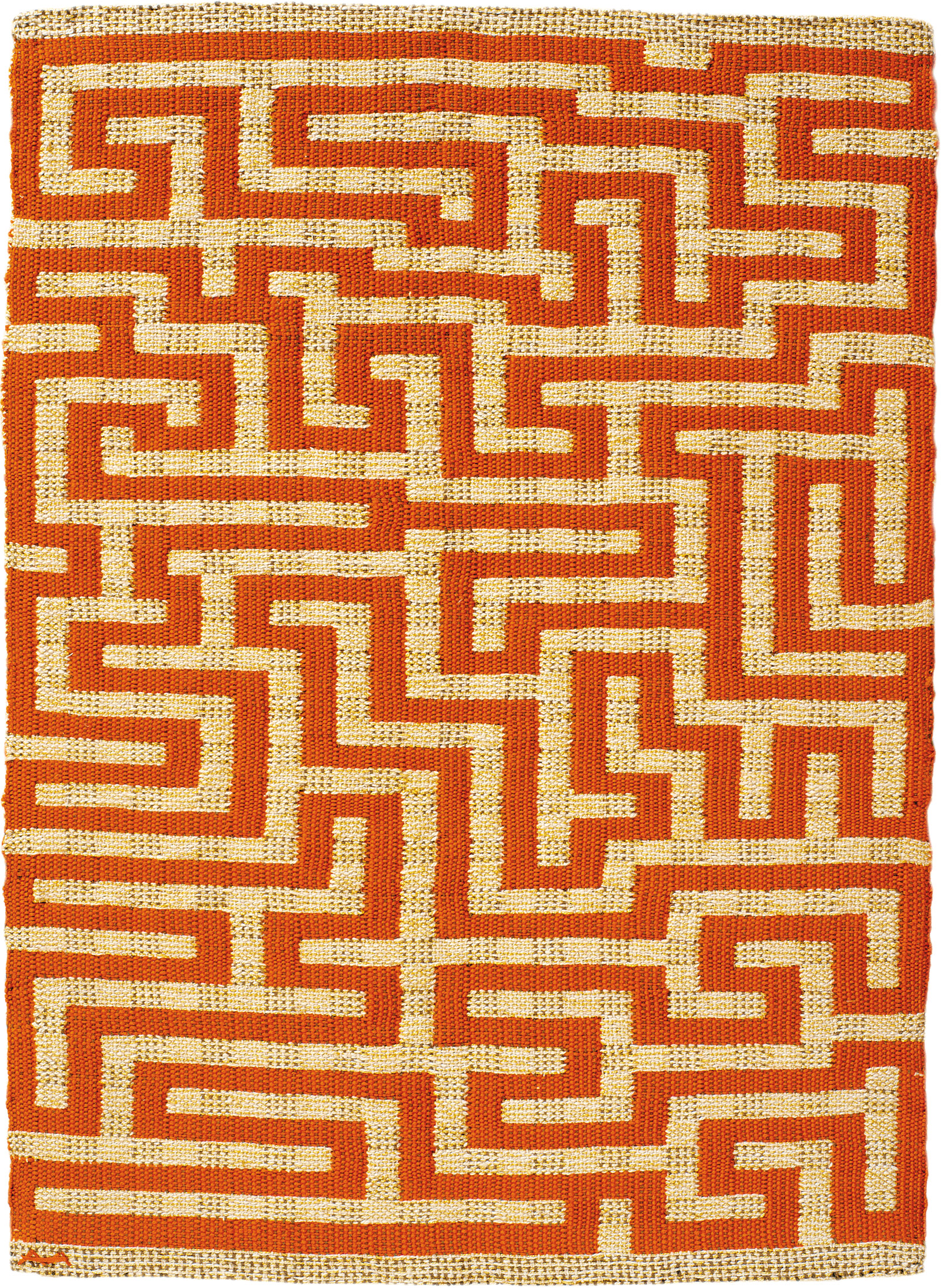

Three weavings by Albers, hung together on a single wall in Chicago, take this show into the stratosphere. The largest, Red Meander, is only a little over two feet tall, but its modest dimensions generate a compact, concise monumentality. While the zig-zagging pattern may well derive from some Mesoamerican model, there is nothing particularly Mexican or Mesoamerican about Red and Blue Layers and Development in Rose II. Albers isn’t commenting on the textile traditions of the Americas so much as she’s diving deep into them and finding herself there. She’s at her ease; it’s the alert ease of the virtuoso. There are no overtly rebellious gestures, no rough edges or fancy fringes or breaks in the surface. The weaving itself is revelatory.

In Red and Blue Layers, the vertical field is stacked with chromatic sequences, and the relatively regular overall rhythm is complicated at every point with eruptions of red, blue, or white thread. There are tiny twists and concavities and convexities of thread of one color or another. Each time you think you’ve grasped a pattern, Albers shifts it very slightly, so that likeness gives way to unlikeness in a dialogue full of the subtlest possibilities. If there is something geological about the striated space of Red and Blue Layers, Development in Rose II embraces a more elusive poetry, with the overall warm haze of threads gathered into ripples of stronger color and texture. As for Red Meander, it is the most bluntly affirmative of these three compositions, except that the more you look, the more you realize that its lucidity is labyrinthine—an enigma in plain sight.

The power of Red and Blue Layers, Development in Rose II, and Red Meander can’t help but complicate the story that Ryan aims to tell with “In a Cloud.” Despite Albers’s interest in the textiles of Mexico, the works from the Americas that she included in On Weaving came mainly from Peru, although she did include one Mexican serape from Querétaro. For Albers, who also surveyed ancient Egyptian and medieval European textiles in her book, the imperatives of form confounded time and place. Her curiosity about Mexico was part of a broader, more general curiosity. The art and design of the entire world was her school. The discipline of textiles was related to the discipline that any artist embraced when confronting the possibilities of a two-dimensional surface. These placid masterworks, with their absolute command of surface, geometry, and symbol, bring to mind the paintings of Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian, but also pre-Columbian Peruvian and medieval European tapestries. Measured against her achievement, much of the work in this exhibition suggests chance encounters, skirmishes, improvisations, and even impersonations.

Albers and Hicks, whose enthusiastic responses to the textile traditions of Mexico and Central and South America were temperamentally and philosophically distinct, could open up a useful discussion about the many questions raised by this show. For Albers, the authority of the craft traditions was crucial to their greatness, and it was by embracing that authority that she came into her own. For Hicks, authority was achieved through the questioning of authority. Like all of the artists whose work is gathered here, they were looking to the artisanal past for some key to the artistic future. It may be that for an artist who was a woman, embracing and reimagining crafts traditions that had all too often been denigrated was a way of beginning to consider (or reconsider) her own place in the world. While “In a Cloud” begins by encouraging us to admire, at least through photographs, ceramics and textiles and other artifacts by craftspeople whose names we don’t necessarily know, the real theme of the exhibition is what women with more conventional art school backgrounds made of what they had seen.

“In a Cloud” is so smoothly, appealingly installed that it’s bound to be a winner with museumgoers. But the more you think about it, the less sense it makes. The midcentury Mexican setting meant radically different things to different artists. Beyond the fact that all the artists included are women, I’m not sure what the organizing principle actually is. The wonderful sculptor Ruth Asawa was in Mexico only briefly. Although it’s interesting to know that her technique of building hanging objects out of wire mesh was originally inspired by the wire basketry that she encountered in Mexico, her biomorphic forms and subtle chiaroscuro probably owe more to modern European and older Asian sources than to anything she found south of the border. Sargent’s rugs would be a striking addition to many an interior, but to put her work in the same setting as the infinitely subtler inventions of Albers and Hicks can’t but diminish the minor decorative effects she achieves. As for Álvarez Bravo’s photomontages, although when presented as murals they provide striking backdrops in this show, they recapitulate the angular strategies of the Russian Constructivists without adding much of a personal touch.

Ryan clearly wants to tell a number of stories that haven’t been told, at least not in the United States. Álvarez Bravo, who struck out on her own after the end of her marriage to the photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo, may not be a formidable artist, but she is certainly a figure worth knowing. She seems to have had a levelheaded estimate of her own achievement, if we can take her at her word when she explained, toward the end of her life, that “if there is anything useful in my photography, it will be as a chronicle of my country, of my time, of my people.” That documentary spirit fits easily with much of the work in a show that is as focused on social history as on art history. What may be most worth remembering about Sargent and her husband aren’t the rugs that they sold at their shop but their Bazaar Sábado, where Mexican and foreign artists, artisans, and designers exhibited and sold their work. It is still operating today in Mexico City, more than half a century later.

One of the elements in Ryan’s story that she doesn’t quite know what to do with is the marriages that were an essential aspect of a number of these women’s lives. Albers, Álvarez Bravo, Porset, and Sargent were married to men who were very much artistic and creative colleagues, but the men have to be sidelined in order to fulfill the exhibition’s scheme. While I understand and salute Ryan’s desire to put the women center stage, it seems a shame that these modern marriages, which obviously involved some considerable measure of mutual artistic respect, aren’t given more of a place in the story told here. To present these women as solitary figures robs them of the full complexity and richness of their work, especially in an exhibition that is meant to explore the networks and communities that made Mexico such fertile ground for creative achievement in the midcentury years.

“In a Cloud” offers the pleasures of a sort of scrapbook, with vivid bits and pieces presented but never really assembled into a convincing whole. If the guiding principle here is Porset’s assertion that there is design in everything, that is of course only the beginning of the story. What neither Porset half a century ago nor Ryan today may be willing to confront are the romantic yearnings that have animated nearly everybody who’s involved. While American travelers, whether artists or not, have found themselves besotted with Mexican culture, it seems that Mexican artists have had their own kind of romance with the Mexican past and the crafts traditions that persist even today. The nature of this romance continues to challenge and confound artists, art historians, curators, and museumgoers alike. The public fascination with Kahlo is part of it. So are the shows focused on Mexican–US relations that our museums continue to produce. What we have here is one piece of the much larger puzzle of our multicultural world. We want to join the similar and the dissimilar, the particular and the universal. It may not be easy, but when it happens, the results are nothing short of miraculous. Only consider the case of Anni Albers, a German-Jewish woman forced to flee to the United States who reveled in the civilizations of Mexico and South America.

This Issue

January 16, 2020

The Designated Mourner

Is Trump Above the Law?

It Had to Be Her