For ninety-nine years a single family ruled Rome. Five of its members in turn controlled the government and the army. But this was not a monarchy: none ruled by right, and the institutions of the old Roman republic remained in place—the consuls, the Senate, even the elections.

This peculiar regime owed its origins to one remarkable man. Gaius Octavius Thurinus was just a teenager when he abandoned the quiet life of the Roman landed gentry in 44 BCE to take up arms against the assassins of his great-uncle Julius Caesar, who had adopted him in his will. For the next thirteen years he fought Caesar’s enemies and then his own. He took advantage of his adoptive father’s posthumous deification to assume a new name: Imperator Caesar Divi Filius—“General Caesar, son of a god.” And finally, in 31 BCE, when he was thirty-one, he defeated the combined fleet of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium to win control of the Roman Empire.

He governed the Roman state for forty-six years through a series of familiar Republican appointments, but outside their traditional restrictions. At first he served continuously as consul, by tradition a one-year post. After eight years he vacated that office but retained the powers of a tribune of the plebs, which allowed him to veto in the interests of the Roman people any legislation, election, or administrative action. At the same time, he transformed Rome’s conscript citizen militia into a standing professional army, which he controlled, since the Senate had granted him military powers throughout the empire greater than those of any other commander. The term he used to describe his anomalous position was Princeps, or “First Man,” and in 27 BCE the Senate awarded him the title Augustus, “consecrated,” the name by which he is known today.

Dictatorship is one thing, dynasty quite another. The Romans had forcibly expelled their monarchy in the sixth century BCE and could not stomach its return. Athough Augustus enthusiastically promoted family members to positions of political and military power, he publicly denied any dynastic ambitions. Perhaps he was telling the truth: succession planning is not the only possible explanation for the preferment of one’s own family. Even on his deathbed in 14 CE, he was said to have been discussing a variety of senators as possible successors. But with his demise, and after a show of great reluctance, his stepson Tiberius took power.

Tiberius was by then an experienced general and politician in his mid-fifties, but he had in the past shown hesitation about a career in public life. While in his thirties, he even withdrew entirely to Rhodes for several years, before returning to Rome to be adopted by Augustus and to take up formal powers very close to his. And when he became Princeps in his own right, his enthusiasm failed again. He neglected affairs of state, relied on treason legislation to silence dissent, and retired again for the last eleven of his twenty-three years in power to a private villa on Capri famous for the size of its pornography collection as well as for the “flocks” of boys and girls kept on hand to cater to his unusual tastes.

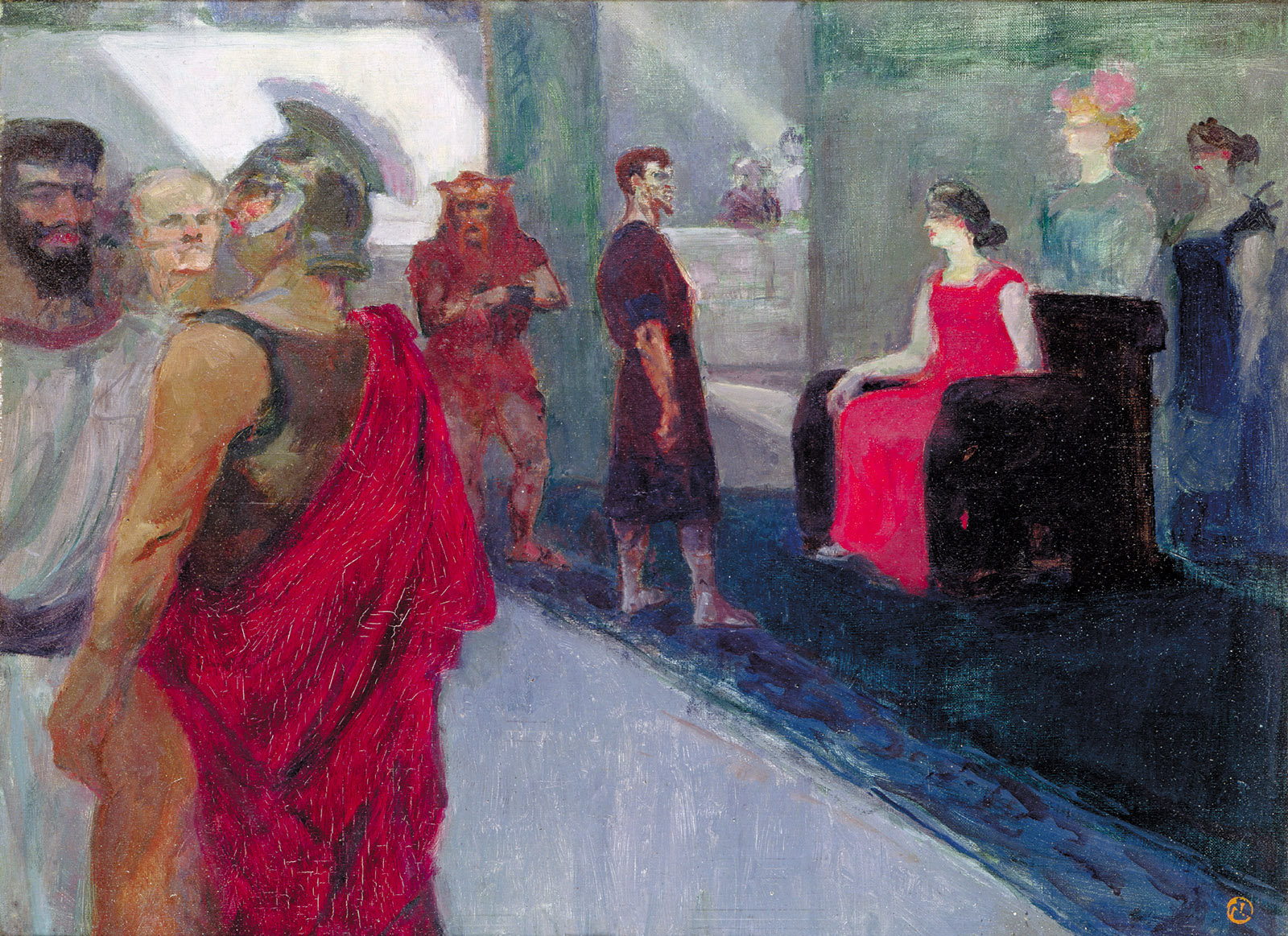

His successor was his great-nephew Caligula, a young man of twenty-four with little experience of politics or war. At first he was popular, and he bolstered his position with lavish games and tax reform. But he quickly became better known for sexual intrigue, capricious executions, and a fondness for wearing women’s shoes. More worryingly, he displayed premature pretensions to divinity, building a temple to his own spirit, with a giant cult statue of himself that was dressed every day in outfits to match his own. After less than four years he was assassinated along with his fourth wife and only child, a daughter.

The accession of his uncle Claudius was a surprise. The fifty-year-old was widely assumed to be weak of mind as well as body, part of the proof being his substantial corpus of scholarly works, including a twenty-volume history of the Etruscans. He nonetheless governed for thirteen years, and well enough to be formally deified on his death, the first time this had happened since Augustus. He renovated the empire’s infrastructure of ports, roads, and aqueducts, enlarged it with the conquest of parts of Britain, and introduced to the Roman alphabet three new letters, which did not survive him.

The final member of the family to rule was Claudius’s teenage stepson and great-nephew Nero, whose thirteen-year reign was marked by successful wars on the fringes of the empire and cultural investment at its center. Later historians linger somewhat unfairly on Nero’s appearances as a singer, which it was said spectators faked death to escape; his participation in the Olympic Games, where he won every event he entered including the ten-horse chariot race, despite having been thrown from his chariot and retiring from the track; and the rumor that he set fire to Rome and then sang of the fall of Troy as he watched it burn. More reliable reports have him ending the familial succession by kicking to death his second wife, Poppaea, best known for bathing in the milk of she-donkeys, along with their unborn child. Conspiracy and revolt marked the final years of his reign, and his family’s hold on Rome ended with his suicide in 68 CE during a military coup.

Advertisement

The real question is not why this dynasty ended, but how it happened to rule at all. It is hard to overstate how unusual it was. Powerful political families are of course common, from the Borgias to the Kennedys, and were already a well-established tradition in Rome. But hereditary dictatorship is rare in supposed republics, ancient or modern. Libya seemed on the path to it before Muammar Qaddafi’s overthrow, the Assads have so far managed two generations in the Syrian Arab Republic, but the only close modern parallel for Rome’s multigenerational family autocracy in a country that claims explicitly to be a republic is the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Again the story begins with a young man abandoning provincial life in his late teens for military resistance: in Kim Song Ju’s case against Japanese imperialism, during which he acquired a new name, Il Sung, a star or the sun. With the defeat of Japan in 1945, when he was thirty-three, he returned to the Soviet-controlled territory of North Korea to build an army and lead his country to independence in 1948. Officially known as the Great Leader, he also filled more conventional offices, serving for more than two decades as premier as well as supreme commander of the army. He gave up the premiership in 1972 and was awarded the newly created office of president by the Supreme People’s Assembly. After his death he was named eternal president.

Again a family succession wasn’t part of the advertised plan. Kim Il Sung was still writing disapprovingly of dynastic rule in the autobiography he published in the final years of his life, although he had awarded family members political honors and positions throughout his years in power. His eldest son, Kim Jong Il, seemed at first reluctant to participate, disappearing from public life for a period in the 1970s, when he was in his thirties. In 1980 he returned to assume a series of positions in the party’s Politburo, Secretariat, and Military Commission; in 1991 he was promoted to commander of the army, and after his father’s death in 1994 he became general secretary of the Korean Workers’ Party and Dear Leader. He still preferred the company of entertainers to politicians, and amassed a famously large film collection while neglecting the economic problems that brought famine to North Korea in the 1990s. After he died in 2011, the party named him general secretary for eternity.

His son and successor, Kim Jong Un, was a young man in his twenties with far less experience than his father, but he quickly made his mark as a forceful and creative politician, amid persistent rumors of family rivalries and political killings. The parallels between Kim Jong Un and Caligula are, of course, only suggestive. The Supreme Leader, as he is known, has already ruled for longer than his Roman counterpart, and unlike him has not yet appointed a horse to a priesthood or deified his sister, although Kim Yo Jong did join her brother for diplomatic talks with both South Korea and the US. And one uncle at least, Jang Song-thaek, lost his chance to succeed him in 2013, when he was executed by firing squad for treason.

The comparison with North Korea not only highlights the exceptional nature of the Roman dynastic experiment but can help to explain its success: what these two isolated examples of dynastic republics share may well be what makes them work. In neither case is the authoritarian nature of the regime disguised, with citizens taking oaths of allegiance to the dictator, but in both his power also rests largely on a cult of personality. This involves supernatural elements—according to later official legends, Kim Il Sung could walk on water and turn pine cones into bullets, while it was said that Augustus could silence frogs and tame eagles, and that when he first entered Rome as Julius Caesar’s son, a rainbow formed around the disk of the sun—but it also emphasizes that the ruler is a father and a family man.

Advertisement

In his early years in power, Kim Il Sung was regularly depicted surrounded by his family, and his paternal responsibility extended to the country as a whole: the first phrase North Korean children were supposed to learn was “Thank you father Kim Il Sung.” On his birthday he would give every child in the country under ten a kilo of sweets. This custom was continued by Kim Jong Il, whose courtesy titles included Father of the People and Beloved Father, and now under Kim Jong Un. The adults don’t do so well: in 2013 the Brilliant Comrade reportedly celebrated his birthday by giving his senior aides copies of Mein Kampf. The Kim family remains the center of attention: a grand mausoleum houses the remains of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, and their pictures decorate public and private buildings throughout the country, as well as the lapel badges worn by every citizen from the age of twelve.

Augustus too built an immense family mausoleum that still stands in central Rome, as do the remains of monuments he dedicated in the names of relatives, including the porticus of his sister Octavia and the theater of her son Marcellus. Octavia personified the ideal Roman matron who lived for family and state: she agreed to marry Mark Antony in 40 BCE to seal a temporary truce between him and her brother, endured his subsequent desertion to Cleopatra, and after they both died brought up Cleopatra’s surviving children alongside her own. Augustus adopted Marcellus, his oldest nephew, and went on to adopt a succession of other male relatives, including Tiberius, after Marcellus’s death in 23 BCE at the age of nineteen. Toward the end of his reign the phrase “Domus Augusta”—the first family—came into use, making his the only Roman political household to be known not by its name but by its rank.

Augustus also diligently promoted family values in the state, passing legislation that gave Romans incentives to marry and produce legitimate children, and that criminalized adultery. These values extended to his own family: he had his daughter and granddaughter taught the traditional women’s arts of spinning and weaving, and he forbade them contact with men outside the family. In 2 BCE the people and Senate acclaimed Augustus pater patriae—Father of the Fatherland.

This emphasis on family and fatherhood is one way such regimes make themselves acceptable to their subjects. It also makes sense of the smooth transition from dictatorship to dynasty in North Korea, providing a clear route of legitimacy from father to son. In Rome, however, things were more complicated: not a single ruler in Augustus’s dynasty was succeeded by his biological offspring. As Guy de la Bédoyère emphasizes in Domina, his new history of the imperial family, the repeated failure of the male line meant that the dynastic bloodline, and therefore the dynasty itself, relied on women. This helps account for the highly visible public role of women like Augustus’s daughter, Julia, his sister Octavia, and above all his wife, Livia, ancestor of all four of his successors.

De la Bédoyère adopts a novel structure for his book, organizing it as a series of lives not of the male rulers but of their female relatives. As Robert Graves demonstrated eighty years ago in I, Claudius, the strong characters and sometimes scandalous behavior of the women of the Domus Augusta can make for absorbing historical fiction. In Domina, however, the same material is often dense, repetitive, and frustrating.

One obvious difficulty is that we know very little about these women, which leads to lengthy discussions of unanswerable questions. Did the women of the Augustan household read books? It’s not clear. Did Livia accompany Augustus on diplomatic visits abroad? Hard to tell. Elsewhere, de la Bédoyère simply takes the claims of later Roman writers on trust: “Had there not been some sort of story in the first place, Tacitus, Suetonius and others would not have troubled to tell it.”

There are always social and financial benefits in being a member of the ruling family, even for its women, but de la Bédoyère exaggerates, along with those same Roman commentators, the extent to which these women aspired to or even exercised real power. Although Augustus gave Livia a variety of public honors and privileges, her reported activities were focused on restoring women’s shrines, promoting her family, and protecting female friends from the full force of the law. In his attempt to show that “by some of the public at least she was perceived as the other half of Augustan power,” de la Bédoyère stretches the contemporary evidence too far: a coin issued in Egypt depicting her with the legend Livia Sebastou does not translate as “Livia Augusta [empress]” but simply “Livia, wife of [the] Augustus.”

Caligula’s sister Agrippina, who became her uncle Claudius’s fourth wife, was the first imperial consort to be given the courtesy title Augusta in her husband’s lifetime. She was also, de la Bédoyère insists, “in fact if not in name, joint ruler” and was “presented to the public as such.” I’m not so sure: like her predecessors, Agrippina could put in a private word for (or against) people, but when she accompanied Claudius on official business, she sat separately. It is possible that some form of informal regency was reflected in her appearance on her son Nero’s earliest coinage: he was, after all, only sixteen years old. Or perhaps, as the wife of a god and a dowager first lady, she was simply a useful symbol of continuity and divine favor for the teenager’s precarious new regime: in provincial sculpture and private cameo portraits she crowns him, and when she attended the Senate she was hidden behind a curtain. It was not until a century later under the Severans, another dynasty preserved by a female bloodline and the subject of an epilogue in de la Bédoyère’s book, that a Princeps’s mother could openly attend meetings of the Senate.

In fact, it seems that the only serious political activity women could undertake within the earlier regime was against it, episodes trivialized by their male relatives or later writers as sex scandals. Julia was exiled for adultery in direct contravention of her father’s legislation, but only after she took up with Mark Antony’s son and appeared in the forum publicly to garland the statue of Marsyas, a well-known symbol of political liberty. Claudius’s third wife, Messalina, is best known to posterity for her fondness for specialist parties, culminating in her winning a sex competition with a courtesan, but her downfall and murder came after she engaged in a pseudo–marriage ceremony with the consul-designate Gaius Silius, prompting fears of a coup. And although the Roman historian Suetonius suggests that Nero’s stepsister Claudia Antonia was killed for turning down his proposal of marriage, the charge was plotting against the regime.

This lack of evidence for real political power is on its face surprising in an era of extraordinary change, especially for women. Decades of civil war had opened up new opportunities. The mighty Fulvia, the first wife of Mark Antony, commanded troops. Augustus passed legislation exempting women from guardianship (the requirement to get permission from a male guardian for financial transactions) and increasing their right to inherit property if they bore enough children, pragmatically combining the new realities with his family values campaign. Women emerged over the following decades as public benefactors and patrons, erecting statues, funding buildings, and supporting their communities financially throughout Italy. Outside the Roman Empire, they ruled as monarchs in their own right: Cleopatra of Egypt, Musa of Parthia, and Boudicca of the Iceni.

These queens all inherited power from their fathers or husbands, but that is not a phenomenon limited to monarchy: in republican regimes, too, membership of leading political families is often how women get the opportunity for real political power themselves. Indira Gandhi’s father had been prime minister of India before her, Benazir Bhutto’s of Pakistan, and the two women who have served as prime minister of Bangladesh were respectively the wife and daughter of former presidents. The problem for the women of the Domus Augusta was that the regime was neither a monarchy nor a republic, but a radical and fragile combination of the two, sustained by a deeply conservative ideology promoted though their largely powerless bodies.

This means that while these women helped to sell dynastic succession to the regime’s subjects, they can’t help explain how it managed to rule in the first place. Livia and Agrippina did play some part in the elevation of their own children to power, in particular by delaying news of their husbands’ deaths until their sons’ positions were secure. Both sons were, however, signally ungrateful. When Livia died in 29 CE, after sixty years as the wife or mother of the head of state, her son Tiberius failed to return to Rome for her funeral before putrefaction had set in, and then vetoed her deification, overturned her will, and purged her friends. Nero went further, actually orchestrating Agrippina’s death: after the failure of assassination plans involving a self-collapsing bedroom ceiling and then a self-destructing boat, she was eventually stabbed to death on hurriedly trumped-up treason charges.

The question of succession, however, reflected the brutal realities of a military regime: a mother’s intervention on her son’s behalf only worked if the soldiers agreed to it. From the beginning, the choice of ruler depended above all on the Praetorian Guard, the elite army unit charged with protecting the Princeps and Rome itself.

When Augustus died, Tiberius’s first action was to equip himself with a Praetorian escort, and Praetorian cohorts helped put down a mutiny against him. Once in power, he increasingly depended on the Praetorian commander, Sejanus, and for five years left him to govern Rome alone. The next Praetorian commander bought Caligula’s favor with the services of his own wife, and was said to have ensured his succession by suffocating Tiberius. Another Praetorian commander killed Caligula four years later, and the Senate’s brief attempt to restore the Republic was outmaneuvered by other Praetorians, one of whom found Claudius cowering behind a curtain in the palace. They took him to their camp to proclaim him Princeps, and he rewarded them with a bonus worth five years’ salary, the same price they were paid by Nero on his accession thirteen years later.

However unusual, dynastic dictatorship is not that hard to establish if it suits military interests. But this means that the army, not the family, ultimately controls the succession.

This Issue

January 16, 2020

The Designated Mourner

Is Trump Above the Law?

It Had to Be Her