Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Work of Nikolai Leskov,” rich in aphorism and vatic utterance, has for many years been a point of reference I return to when thinking about narrative and why its various forms play such an important part in our lives. Like all of Benjamin’s work, the essay stands in dialogue with a number of other texts that had talismanic value for him: not only by the author ostensibly under discussion, the nineteenth-century Russian novelist and short-story writer Leskov, but also Georg Lukács, Paul Valéry, Ernst Bloch, and Johann Peter Hebel. So it is gratifying to have this slim volume, edited by the translator and critic Samuel Titan, that brings “The Storyteller,” newly translated by Tess Lewis, together with excerpts from all of these writers and others (Herodotus, Montaigne) who are inseparably stitched into Benjamin’s thinking. It also contains other pieces by Benjamin that offer first approximations of “The Storyteller” and provide glosses on it, including one of his radio tales for children, the captivating “The Lisbon Earthquake.”

“The Storyteller” stages an opposition of the oral tale to the printed novel. The tale comes to life in the milieu of work and travel and trade: it is an oral transaction in the workshop or with a traveler returned to tell his adventures to those at home. Above all, it involves one living person transmitting experience of life to another in a vital exchange. The personality of the storyteller, Benjamin writes, clings to the story “the way traces of the potter’s hand cling to a clay bowl.” Stories are compact; they have a “chaste brevity” that precludes explanation. They unfold within the rhythms of work. The tale offers human counsel. What it transmits, in Benjamin’s strikingly simple term, is “wisdom.”

If storytelling is dying out, so is the art of listening: the creation of a community of listeners around the storyteller. And beyond that, the very communicability of experience is threatened with loss. We no longer know how to share our experiences; we have been impoverished by the shock of the Great War and its sequels:

A generation that had gone to school in horse-drawn streetcars found itself under open sky in a landscape in which only the clouds were unchanged and below them, in a force field crossed by devastating currents and explosions, stood the tiny, fragile human body.

The war that destroyed high European culture is both the symbol and the historical event of the decline of shared experience passed on as wisdom.

Story requires a state of relaxation akin to boredom: “Boredom is the dreambird that broods the egg of experience,” writes Benjamin in a sentence worthy of the Surrealists. He quotes Leskov’s opinion that storytelling is not high art but a craft—“ein Handwerk”—and this leads him to reflect on Valéry’s meditations on the elaborate embroidery of Marie Monnier, the product of infinite patience and the unhurried acquisition of perfection. “The era is past when time did not matter,” writes Valéry. “Today no one cultivates what cannot be created quickly.” And then, in one of Benjamin’s sleight-of-hand transitions, this loss of patient practices of handwork parallels the fading of the “idea of eternity,” which in turn suggests that “the idea of death has lost persuasiveness and immediacy in the collective consciousness.” Death has ceased to be public, and in the process it has lost its authority, which “lies at the very source of the story.”

Now Benjamin can make what may be the central pronouncement of his essay: “Death is the sanction of everything the storyteller can relate. It is death that has lent him his authority.” This authority of death, reflected in the way a storyteller such as Hebel recounts the passage of time—in which the Grim Reaper reappears with the regularity of his figure in a church clock—sets up the contrast to the novel, which Benjamin sees, in the extraordinary phrase from Lukács’s The Theory of the Novel, as a “form of transcendental homelessness.” Lukács sets the novel in contrast to the epic, in which meaning inhabits the life of the hero, whose exploits carry it into eternity. In the epic, meaning is immanent to life, whereas in the novel, Lukács writes, “meaning is separated from life, and hence the essential from the temporal; we might almost say that the entire inner action of the novel is nothing but a struggle against the power of time.”

Lukács points us to the essential function of temporality in the novel. If those novels that best define the genre tend to be long—from Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa through Dickens’s and Balzac’s and Dostoevsky’s and George Eliot’s huge productions, and on to Henry James and Proust—it is because their meanings must be played out over passing time: people age, make mistakes, regret decisions, choose new partners, perhaps learn something about life. This, for Lukács, makes Flaubert’s Sentimental Education the novel of novels, one in which the failure to wrest meaning from the struggle with time leads, at the end, to the compensation of telling stories about it, as Frédéric and his friend Deslauriers in their final meeting engage in “exhuming” their youth. The recounting of memories has become the only pleasure left to them. “Only in the novel,” Lukács claims, “does memory occur as a creative force affecting the object and transforming it.”

Advertisement

What this demonstrates, in Benjamin’s use of Lukács, is a fundamental distinction between story and novel. In the one, we have the “moral of the story”; in the novel, it is a question of the “meaning of life.” Whereas the listener to the story is in the company of the storyteller, the reader of the novel is “solitary, more so than any other reader.” He appropriates the novel, “devours the book’s contents as fire consumes logs in the fireplace.” What readers look for in the novel is that which is inaccessible to them in their own lives: the knowledge of death. It is with the end of a life that its meaning becomes apparent. And that is what we seek in the death (which may be figurative but is preferably literal) of the fictional character: “The flame that consumes this stranger’s fate warms us as our own fates cannot. What draws the reader to a novel is the hope of warming his shivering life at the flame of a life he reads about.”

So it is that solitary modern readers consume fiction in order to understand the meaning of life by way of a surrogate who has reached the end and thus retrospectively cast meaning on all that has gone before. The end-orientation of novels, their constant attempt to transform experience into meaning, or, in the terms used by Jean-Paul Sartre, to make living into adventure, into a life with a destiny, may be what fictional narrative is all about (and why Sartre eventually found it untrue to experience). It is designed to rescue meaning from passing time.

The novel brings to the solitary individual something of a simulacrum of the sociality of listening to a story, but always with a residue of knowledge that modernity has shattered true community. Think of the death-bed scene in the traditional novel, from Clarissa’s edifying end to Old Goriot’s final rants about his daughters’ betrayals and the collapse of family and society in Balzac’s Père Goriot, or Barkis’s “going out with the tide” in Dickens’s David Copperfield, or Jude Fawley’s final Job-like pronouncements in Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, on to Milly Theale’s final absolution of Merton Densher in James’s The Wings of the Dove. These moments of transition from life to death, often from one generation to another, offer the transmission of a kind of wisdom, a final summing-up on life.

Proust, one of Benjamin’s favorite authors, makes the argument that it is only through a fictional character that we can understand the profound changes of life, hidden from us in the routine passage of time in our own lives. The heart changes in life, that is our worst sorrow, but we know this change only in reading. The novel should, then, serve as “an optical instrument” through which the reader becomes “the reader of himself,” understanding through fiction what is obscured to him in the perpetual wandering, the “perpetual error” that we call life.

Benjamin in his claim that death is the “sanction” of narrative subscribes to this same view: that reading a narrative is the only meaningful experience we can have of life. Telling trumps living, as in the final scene of Flaubert’s Sentimental Education. Memory has become transformative. Yet that is a sad wisdom, which may make us want to recover the live communicative situation of storytelling. There is in Benjamin, here as elsewhere, a sophisticated nostalgia that holds in balance loss and the insight it provides. “The art of storytelling is coming to an end because the epic side of truth, that is, wisdom, is dying out,” he writes. But then he adds:

This phenomenon is far from new. Nothing would be more foolish than to consider it merely a “symptom of decline” much less a “modern” symptom. It is, rather, a side effect of historical secular forces of productivity that have gradually eliminated the storyteller from the realm of living speech and at the same time have made a new beauty visible in what has disappeared.

We can find versions of this dialectical nostalgia brought into being by the “historical secular forces of productivity” in many nineteenth-century writers, first of all Balzac, the novelist crucial to Lukács and also to Benjamin’s favorite writer of Paris, Baudelaire. Over and over again, Balzac stages scenes that give us “the oral in the written,” simulations of the situation of oral storytelling. In Another Story of Womankind (Autre étude de femme), for instance, at a late-night gathering at the home of the novelist Félicité des Touches (broadly based on George Sand), the illustrious guests take turns telling stories to this elite set of listeners. “All eyes listen, gestures ask questions, and physiognomy responds.” The value of the story lies as much in its hearing as its telling. The last tale of the evening is told by the doctor, Horace Bianchon: a tale of betrayal, jealousy, and a punishment so chilling that when it is finished his listeners are silent, and the circle breaks up.

Advertisement

Framed or embedded tales—tales within tales—were popular with nineteenth-century writers, not only Balzac but also Maupassant and Kipling and Saki and Conrad, to name just a few, no doubt because they can dramatize listeners’ reactions to and interpretations of what they have heard. Think of the telling of and the listening to Marlow’s account of his adventures with Kurtz on board the ship Nellie anchored in the Thames estuary in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. By the time Marlow has done with his tale, its grimness seems to have infected the whole scene. It has been so absorbing that the Nellie, bound down the river, has lost the turn of the tide. And we reach the final line:

The offing was barred by a black bank of clouds, and the tranquil waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth flowed somber under an overcast sky—seemed to lead into the heart of an immense darkness.

Marlow has in the course of his tale come face-to-face not only with Kurtz’s transgressions of civilization and his bleak death but also with his last words, his final pronouncement on life: “The horror! The horror!” If Marlow continues to affirm that Kurtz was “a remarkable man,” it may be because his scene of death confronts ethical nihilism and existential nothingness without flinching.

Heart of Darkness offers matter for all sorts of reflections on the place and effect of storytelling, coming to us in a written simulation. By Conrad’s time—well on the way to Benjamin’s—the oral tale has taken up its home within the written and the printed; it is tinged with a sense of its belatedness, so to speak. Balzac stands at the point where the oral tradition still exists but will be saved only by transcription—just about the moment when the Grimm Brothers were assembling their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (the first volume was published in 1819) in order to preserve an oral tradition in print. Balzac’s nostalgia for oral storytelling (a kind of “Old Régime” of narrative, he calls it) is traversed by his lucid awareness that he writes and publishes at the dawn of what came to be known as “industrial literature” (the phrase was coined by the critic C.A. Sainte-Beuve, who disliked Balzac intensely, to describe novels serialized in daily newspapers and designed to make money).

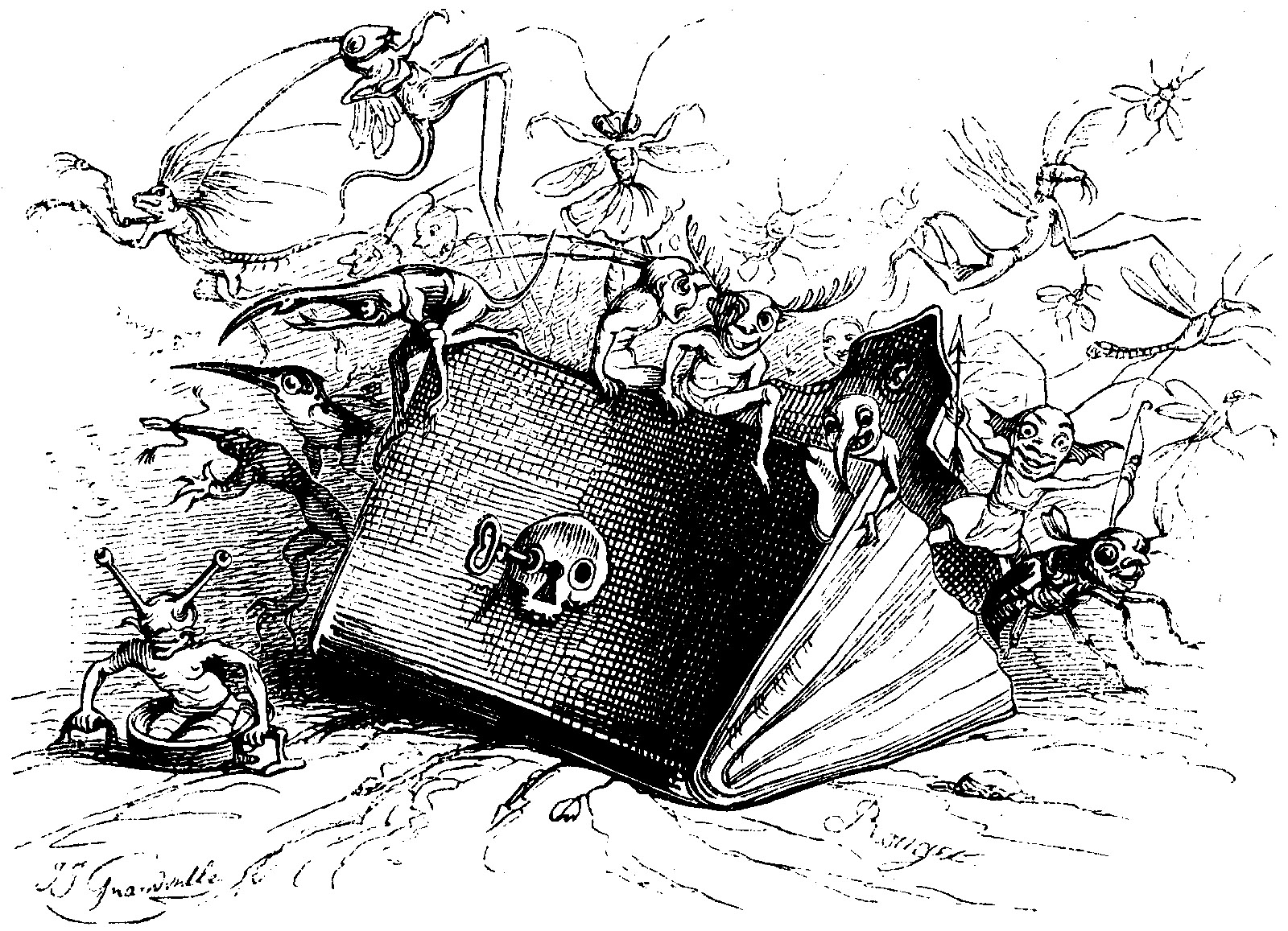

One of Balzac’s greatest novels, Lost Illusions, recounts the adventures of a sometime poet who is caught up in the newly powerful forces of journalism and experiences the transformation of literature into a commodity. According to Lukács, who wrote often on Balzac, the profound subject of Lost Illusions is “the capitalization of spirit.” The products of mind become objects of commercial exchange. Balzac records a moment when the old values of aristocracy and wealth rooted in land give way to the nascent speculative capitalist economy, dominated by financiers such as his corrupt fictional banker, the Baron de Nucingen. Everything in Lost Illusions speaks to the power of the “devouring” printing presses that are featured in the first paragraph of the novel. The oral is henceforth a nostalgic echo within print.

Benjamin understands that orality can now only be preserved through literacy. He surely knows that Leskov, a businessman, journalist, and author of novels as well as tales who lived from 1831 to 1895, offers an example of a later and sophisticated simulation of orality. Benjamin’s preference for the oral tale over the novel is at the same time sincere and strategic. It enables him, as he puts it, to see the beauty in what is vanishing and to suggest, along with Lukács, why the novel has become the modern genre that has eclipsed, maybe devoured, all others. Benjamin offers an earlier version of his polemic on the reading of novels in a 1930 article on Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz: the novelist, he says,

is the truly solitary, silent individual…. The birthplace of the novel is the individual in his solitude who is no longer able to speak about his most important concerns in an exemplary way, who has no one to counsel him and has no counsel to offer.

The novel, he claims, has attained an “outrageous proportion” in our reading. And in a fragment from about 1933: “All books should not be read in the same way. Novels, for instance, are there to be devoured.”

But such statements imply a recognition that there is no turning back from the part that novels have come to play in our modern self-understandings and our ways of deciphering other people. There is no way out from the novel, and the indebtedness of “The Storyteller” to Lukács’s Theory of the Novel shows clearly enough that whatever nostalgia Benjamin harbors for the epic and the oral exists within the written. So it is that he praises Arnold Bennett’s The Old Wives’ Tale on the twenty-fifth anniversary of its publication, in 1933:

Of all the gifts [the novel] offers, this is the most certain: the end…. The novel is not important because it portrays the fate of a stranger for us, but because the flame that consumes that stranger’s fate warms us as our own fates cannot. What draws the reader to the novel again and again is its mysterious ability to warm a shivering life with death.

In the forlornness of our modern condition, deprived of “counsel,” it is the novel that brings us warmth through its capacity to make us understand the end.

The threat to both tale and novel is in fact the same: information (which might best be expressed today, says Samuel Titan in his fine introduction, as “data”). Storytelling risks degradation by its promiscuous overuse in public life. “Story” has entered the orbit of political cant (candidates now all have “great stories” in their backgrounds; “I love his story,” said George W. Bush of one of his cabinet appointees) and corporate branding. The media proclaims story everywhere, as if that were the only form of understanding left in our civilization.

This saturation by the mindless promotion of story argues the need for Benjamin’s rich and acid analysis of culture by way of its literary exemplars, themselves largely dissenters from cultural consensus. Critical attention to the way stories are told and the way they work on us, their listeners, is ever more crucial, in politics, in law, in narratives of “who we are,” as a nation as well as individuals. Failure to understand narrative and its persuasive effects has consequences for the polity itself. When we fail to see stories as ways of representing reality and take them for reality itself, they become myths, such as of the “master race” or the “invasion” of our nation by murderous immigrants. We seem to find ourselves in a confusion of living and telling that needs constant critique.

Benjamin’s analysis of the dying arts of telling and listening to stories is at once an affirmation that other forms—and all forms—of narrative need to be analytically engaged since they are crucial to our self-understandings. He concludes his essay with the vatic observation: “The storyteller is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.” But the essay convinces us equally that beyond righteousness in any simple sense, the novel at its most powerful offers us our best understandings of what it means to live, to have lived, to construct a life.

This Issue

January 16, 2020

The Designated Mourner

Is Trump Above the Law?

It Had to Be Her