A paradox of American presidential elections—especially during the primaries—is that unless a war is looming or underway, voters pay little attention to the arena in which a president has the greatest power to affect their lives. On taxes, education, health care, and all the other domestic issues for which candidates put forward detailed plans, what a president wants will have to be exhaustively negotiated with Congress. On foreign policy, his or her freedom of action is vastly greater. Foreign policy, too, unlike domestic issues, frequently entails surprises—the collapse of the Soviet Union, say—that demand a swift response in unexpected conditions. In their own interest, then, voters ought to want to know what a candidate’s instincts about foreign policy are—what she or he makes of recent history, of global trends, of the threats the US faces, and of what its responsibilities in the world should be.

Candidates should care as well, since history suggests that foreign policy is likely to have a significant effect on their legacy if elected. Of Trump’s nine predecessors over the past half-century, the Vietnam War shaped the administrations of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. The Iran hostage crisis ended Jimmy Carter’s presidency after one term. The Iran-contra scandal dominated Ronald Reagan’s second term, eventually producing convictions of eleven administration officials. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, George W. Bush’s declaration of a “global war on terror,” the war in Afghanistan, and the tragically misconceived invasion of Iraq determined the course of Bush’s presidency and created many of the issues facing his successors.

Donald Trump’s international decisions—they do not amount to a coherent policy—are a further reminder of what is at stake. In just three years he has scrambled allies and adversaries, thrown away international agreements, crippled institutions demonstrably serving US interests, and created opportunity after opportunity for China and Russia to exploit. Nonetheless, until the US killed Qassim Suleimani on January 3, foreign policy was once again nearly invisible in the 2020 campaign. In the Democratic candidates’ first six televised debates, 10–15 percent of the time was spent on foreign policy.

But that proportion reflects what national reporters think is important. Voters hold different views. The Des Moines Register tracked every question asked of all the Democratic candidates at public events in Iowa during three weeks in October and November. Of the 321 questions, fourteen—4.4 percent—were about foreign policy. (Questions about climate change were counted separately.) Elizabeth Warren’s campaign kept a tally of questions asked at her events across the country that counted twenty-seven about foreign policy out of more than six hundred—4.5 percent. Those questions have ranged widely, not clustering around a few issues. Polls are remarkably similar: only 5 percent of respondents name foreign policy as the most important issue. Given these numbers, candidates can hardly be faulted for not talking about it more.

What they have said reveals broad areas of like-mindedness. All the candidates agree that climate change is an existential threat and pledge to immediately rejoin the Paris climate accord. They agree that relationships with traditional allies are crucial to US interests and are committed to rebuilding them—Joe Biden plans to also “reimagine” them, without explaining what that means. They agree that military force should be a last rather than a first resort and promise to reinvigorate and reemphasize diplomacy. And they support a renewed embrace of multilateralism.

They have all pledged to rejoin or in some way rescue what is left of the Iran nuclear deal. (The killing of Suleimani could make this moot: there may well be nothing left of the deal by January 2021.) They agree on ending the war in Afghanistan, though with differences in emphasis and timing. Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang urge a quick departure. Pete Buttigieg notes the need for special forces and intelligence personnel to remain behind after combat forces depart and pledges that the authorization of any US intervention under his leadership will expire after three years. Congress will be forced, he says—though it’s not clear how—to match soldiers’ courage with its own willingness to go on record authorizing a mission. Biden pledges to bring the troops home from Afghanistan during his first term and to focus US efforts there tightly on counterterrorism, but he undercuts that welcome rigor by specifying that any peace deal must protect the rights of women and girls—an outcome greatly to be desired but not a function of a counterterrorism operation.

The candidates also agree that the top priority for a sound foreign policy is the need to rebuild a healthier, less divided, and less unequal democracy at home. Here trouble arises, because the domestic agendas they advocate to achieve that happier state are frequently so long that foreign policy gets lost entirely. This is especially true for Biden, who puts the greatest emphasis on democracy as the foundation of US policy abroad. The first bullet point in the fact sheet that accompanied his major foreign policy address delivered in October is “Remake our education system.” The second is “Reform our criminal justice system.” To be sure, we badly need to repair the fractures in our democracy, but in the years—decades—that that will require, we will need an actual foreign policy as well. History won’t take a time-out while we work to restore what is broken at home.

Advertisement

Trump’s successor, whether in 2021 or 2025, will inherit a uniquely demanding international agenda both with respect to specific policies that need to be reversed and, for the first time in many decades, real uncertainty about what priorities—what strategic vision—Washington should adopt in their place. Most of the Democratic candidates understand that part of Trump’s appeal in 2016 was to Americans who did not believe that US policies abroad served their interests. For fifty years, memories of World War II and the extraordinarily successful internationalist strategy born out of it (the Marshall Plan, the United Nations, and so on), and then the need to win the cold war, were enough to command steady popular support for those policies. But thirty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union and with seemingly unending wars continuing in the Middle East, the support for them is gone. Buttigieg has captured this dilemma most clearly: “Democrats can no more turn the clock back to the 1990s than Republicans can return us to the 1950s, and we should not try.” What should be done instead, however, none of the Democratic candidates has made clear.

The biggest problems Trump will leave behind are well understood, but here, too, answers are not evident. Days after the 2016 election, Barack Obama warned the new president-elect that North Korea’s nuclear program posed his most urgent challenge. Three years later, US policy has lurched from “fire and fury” to “love,” from threats to fawning requests, and from unprepared presidential summits to ill-judged cancellations of US–South Korean military exercises. No agreements have been reached, while North Korea has had a thousand days to make progress on its nuclear and missile programs—time it has not wasted. Wiser men and more professional US administrations than Trump’s have failed to stop Pyongyang’s nuclear advance, but none has produced a comparable record of confusion, futility, and weakness.

The Trump administration’s record on Iran is in some ways even worse because it threw away an agreement to shut down Tehran’s nuclear weapons program that was working and had nothing but threats and sanctions to replace it. The results have been exactly what critics predicted. After a year’s wait to see whether Europe could change Washington’s mind or deliver promised economic benefits on its own, Iran began to meet Trump’s “maximum pressure” with “maximum resistance”: escalating violations of the agreement and more provocative policies across the region. After Washington completely shut down sales of Iranian oil last spring, the Iranians attacked an American drone, oil tankers in the Persian Gulf, and major Saudi oil facilities. Hard-liners in Iran who opposed the nuclear deal have been politically strengthened and confirmed in their belief that the US can never be trusted. The economic impacts of the tightened US sanctions have been severe, prompting large public protests that the government has brutally suppressed. US officials now speak openly about regime change, but even the harshest sanctions have proven ineffective in unseating autocratic regimes. Elites protect themselves, everyone else suffers, while the regimes—in North Korea and Cuba as in Iran—stay in place. Trump’s policy, in short, has been lose–lose: nuclear constraints have been lost and the risk of a shooting war—intentional or accidental—has increased dramatically.

The killing of Suleimani ratchets tensions many degrees higher. Members of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard (of which Suleimani was a leader), if not all Iranians, are unlikely to feel that Tehran’s first response of missile strikes on US bases in Iraq—seemingly designed to avoid US casualties—adequately avenged his death. Americans can expect more retaliation, possibly major cyberattacks, in coming months. And while neither side wants a war, Trump is in the unenviable position of having inflamed an enemy that can act to hurt him at any point during the coming campaign.

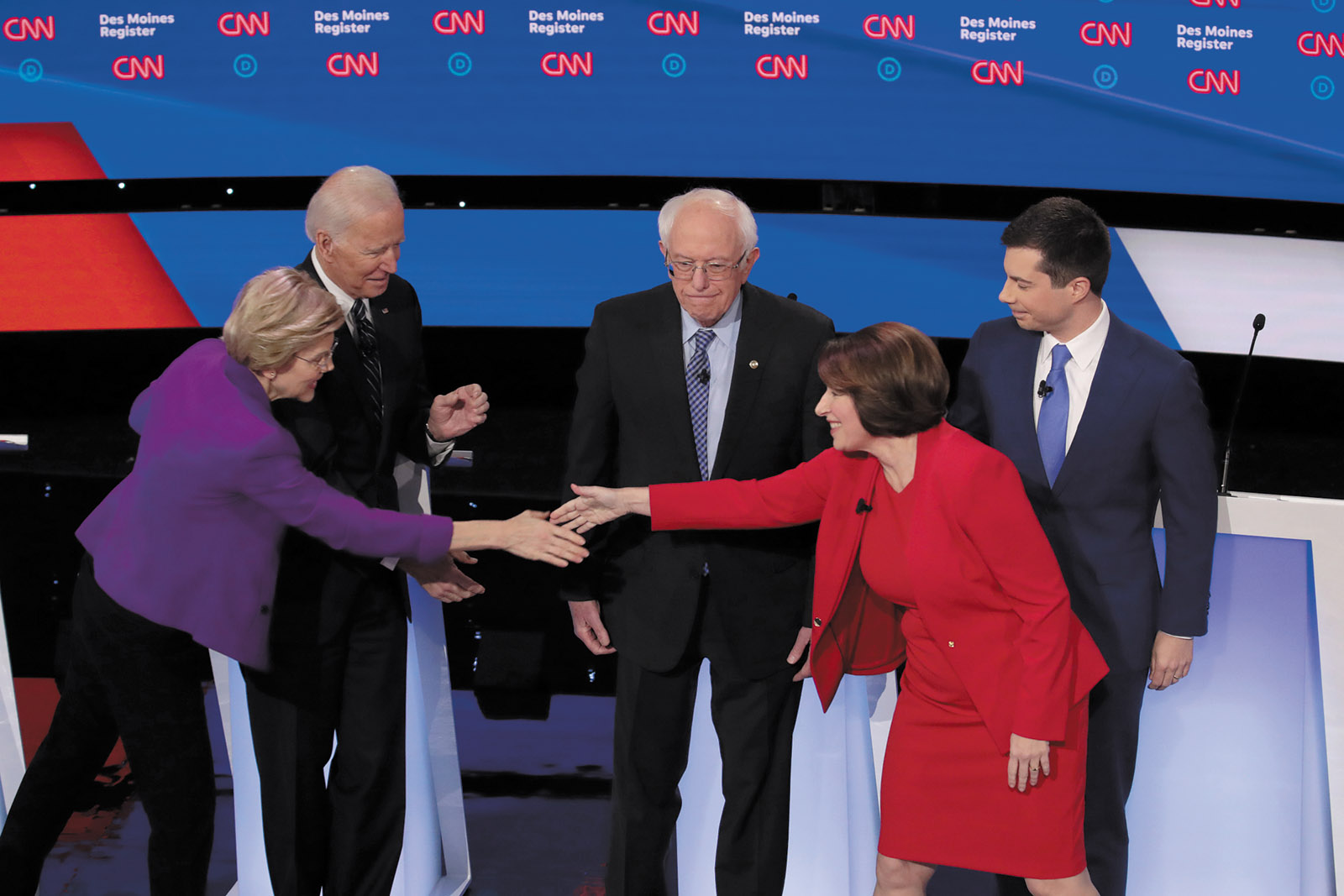

Events in the Middle East in the days immediately following Suleimani’s death shifted Democratic primary voters’ attention from domestic issues to the responsibilities of the commander in chief. With impeachment looming, and with news cycles these days that are often only hours long, it is impossible to predict how long this will last. Candidates’ reactions were true to form. Sanders and Warren highlighted the danger of being dragged recklessly into another war. Biden, Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar focused on the lack of any discernible strategy in Trump’s Iran policy or of a responsible process, including consultation with Congress and with allies, in the decision to act when he did.

Advertisement

So far, the crisis has strengthened the former vice-president and longtime chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: voters feel reassured by Biden’s years of experience. The flip side of experience, however, is the record of judgment, in this case Biden’s vote in favor of George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, which Sanders (who voted against it) and to a lesser degree Buttigieg now raise more forcefully. The new focus may also be a double-edged sword for Buttigieg: although he can point to his military experience, his youth may give voters pause as they contemplate a renewed danger of conflict in the Middle East.

Relations with Russia and China are also dangerously unhinged. Both of these US adversaries now see Trump as an asset. Thanks to administration inaction and to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s refusal to move forward legislation to strengthen election security, Russia will be able to repeat in 2020 at least some of its 2016 success in intervening on Trump’s behalf. The Russian journalist Alexei Venediktov, interviewed in The New Yorker, explained precisely why: Russia sees in Trump a producer of “turbulence.” “A country that is beset by turbulence closes up on itself—and Russia’s hands are freed.”

From Syria, Ukraine, Northeast Asia, and a shaky NATO uncertain of American commitment for the first time in its history, to an American society polarized as never before and becoming inured to being fed a diet of lies, Trump has produced bounteous gifts for Putin. Having pulled the US out of the INF treaty limiting intermediate-range nuclear weapons and refused to extend the New START treaty limiting strategic nuclear weapons, he has raised the specter of a world wiped completely clean of superpower arms-control agreements, the work of half a century of painstaking negotiation. The next president will have only a few days after the inauguration before New START expires to reverse a decision made on the absurd ground that the treaty should not be extended because it does not include China. The treaty limits Russia and the US to 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear weapons each, while China is believed to have about three hundred. Someday, a trilateral treaty may be necessary and achievable; meanwhile, confidence embodied in verifiable arms-control agreements between the two nuclear superpowers must be preserved. Beginning again from nothing would be vastly more difficult. Living with nothing risks a resumed nuclear arms race.

Trump’s China policy has focused single-mindedly on trade. After making the almost meaningless bilateral trade deficit his measure of success and talking blithely of how easy it is to win a trade war, he has backed down, signing an interim deal that amounts to very little. More important structural changes in market access rules and intellectual property protection have been shunted to postelection negotiations. Chinese officials recognize weakness when they see it. Meanwhile, despite the administration’s contentious rhetoric about Sino–US conflict, it has had little to say about the democratic upheaval in Hong Kong or the incarceration of huge numbers of Chinese Uighurs. While there is broad agreement in the US on the need for greater toughness against unfair Chinese trade policies and intellectual property theft, experts see only danger ahead from an approach that does nothing to preserve a degree of mutual trust in the bilateral relationship and fails to recognize the necessity for cooperation on global issues ranging from climate change to nonproliferation.

Trump’s bizarre, self-defeating rejections of American alliances are welcome gifts to Beijing, as they have been for Moscow. In his erratic talks with Kim Jong-un, Trump consistently ignored South Korea and Japan, both directly threatened by Pyongyang. He then demanded, out of the blue, that South Korea quadruple its contribution to the cost of stationing US troops on its soil, a demand that makes no sense economically or strategically. To top it off, he ignored a simmering dispute between these two allies, the cornerstones of America’s strategic position in the Pacific, so that 2019 ended with Beijing stepping forward to mediate between them, which only a few years ago would have been inconceivable—and still should be.

The arena in which Trump’s policies have done the greatest damage while being least recognized is his across-the-board weakening of multilateral problem-solving and therefore the rule of law. He has pulled the United States not only out of the Paris climate accord, the Iran nuclear deal, and the INF intermediate-range nuclear forces treaty, but also the Trans-Pacific Partnership on trade, the UN Human Rights Council, UNESCO, and the Arms Trade Treaty, and he appears ready to kill New START. By refusing to approve any nominees to fill vacancies on the World Trade Organization’s panel of judges, he has damaged, perhaps irretrievably, the world’s foremost body for resolving trade disputes. The irony of this is that over the years the US has won more WTO trade cases than it has lost. The greater damage is that the WTO, with only a single judge left, cannot act on behalf of the more than 150 other states that continue to support it. The message is widely understood: the US now prefers to address trade disputes bilaterally, through the raw power of its economy, rather than through the multilateral, rule-governed mechanisms it has spent decades building.

Notwithstanding the enormity of this set of challenges—and they are only the most immediate of what Trump’s successor will face—the Democratic candidates have had relatively little to say about them. It has become an article of faith for many Democratic politicians that Americans will only support a foreign policy if it is tied directly to their economic well-being, especially that of the middle class. It is impossible, however, to tie the importance of stopping the spread of nuclear weapons to middle-class pocketbooks, for instance, or to describe US strategic interests in Ukraine or Japan or the need for a balanced, long-term China strategy as a matter of near-term economic benefit. The belief that it is necessary to do so, or else to avoid foreign policy entirely, shunts aside a necessary conversation. It likely also underestimates the American voter who may be resentful of domestic policies that have created staggering levels of economic inequality and of foreign policies that seem overly militarized or without clear purpose, but who may be perfectly willing to support a foreign policy they feel makes sense.

Warren’s foreign policy proposals square this circle by transposing her domestic economic pitch to the international level. Endless wars in the Middle East, bad trade deals, global financial risks, and belligerence from Russia and China are all, in her telling, caused by “champions of cutthroat capitalism” nourished by worldwide corruption. The villains in nearly every case are greedy corporations. Whatever one thinks of this worldview, the seriousness with which Warren has approached issues during her campaign is admirable. Her website lists sixty-nine policy plans. Unfortunately, the pursuit of details too frequently leads to utterly impractical results. Her plan for achieving fairer trade deals, for example, includes making negotiating drafts public; adding more advisory committees and labor, environmental, and consumer representatives to existing ones; and promising to seek congressional approval of trade agreements only “when every regional advisory committee and the labor, consumer, and rural advisory committees unanimously [emphasis added] certify that the agreement serves their interests.” Good luck with that.

Warren and Sanders agree on many things, but while she errs in saying too much, he barely touches on foreign policy. You have to scroll far down the Sanders website to find the little he has to say about it. He speaks cogently on the stump about the need to “privilege diplomacy,” to work more closely with allies, and to favor a posture of “partnership, rather than dominance,” but he has not gone beyond such generalities except in calling for changes in the US–Saudi relationship and ending US support that prolongs the killing in Yemen. His long-standing opposition to American interventions in Latin America and his approval of governments that profess concern for the poor have led him to express support for highly repressive leftist regimes in the likes of Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Bolivia. This could well prove to be heavy political baggage in a presidential election.

Warren and, to a lesser degree, Klobuchar are the only candidates who have had the courage to address the country’s mushrooming defense budget ($738 billion for the coming year), which now consumes more than 60 percent of all federal discretionary spending.1 The defense budget, in Warren’s words, “has been too large for too long.” Yet she says only that it should be cut to an undefined “sustainable” level. Klobuchar warns of the “false logic that higher defense spending automatically leads to a better military or a safer nation,” and correctly notes that the defense budget is riddled with “duplicative and unnecessary programs.” She wants a “much clearer look at how money is being spent” and on what, but she leaves it at that. Buttigieg hints that the budget may be too big but avoids reaching any conclusion. Instead, he focuses on outdated priorities, criticizing a budget that spends “more on a single frigate than on artificial intelligence and machine learning.”

Rather than take on the defense budget, it is politically easy to promise to do more for veterans, and most of the candidates do so. Because of his military service, Buttigieg would be the first Democratic candidate in decades to be entirely comfortable talking to and about the military—a significant asset for the Democratic Party, especially in contrast to Trump’s infamous “bone spurs.”2 Buttigieg’s 2019 Veterans Day speech, in which he went off-text to add that it is “better late than never to say thank you—and welcome home” to those who served in Vietnam and were not treated appropriately when they returned, is a powerful reminder that personal service confers a legitimacy in addressing military topics for which there is no substitute.

Given the length of time that Biden has held senior positions in government, it is not surprising that he hasn’t been able to avoid the trap of looking backward on foreign policy. Too often his default answer is “I was the one who” did this or that ten years ago. Worse, his oft-repeated call to “place America back at the head of the table” suggests that he believes that the world has scarcely changed since the cold war. More surprising is how mushy and off-key many of his principal proposals seem. He promises, for example, to convene a global Climate Summit in his first hundred days in office, at which he would use “our moral authority” to persuade attendees to “join the United States” in making more ambitious pledges to cut emissions. Quite apart from the fact that a serious global conference cannot remotely be readied in one hundred days, this proposal seems oblivious to the enormous amount of technical work done by members of the Paris agreement for their regular meetings, to American withdrawal from that agreement, and to domestic policies of the past three years promoting coal and fossil fuels generally, all of which have pretty well extinguished whatever moral authority the US once had on climate change. A few weeks of a new presidency aren’t going to change that.

On the same theme, Biden proposes a global “Summit for Democracy” to be held in his first year. This was an unworkable idea when it was discussed during the Clinton administration and seems even less well suited to today’s world, beginning with the vexing question of who decides what countries qualify as democracies in order to be invited—Turkey? Brazil? Hungary? the Philippines?—and what happens to US policy toward those that aren’t included. The underlying notion that President Biden could take enough significant steps in a few months to restore the “democratic foundation of our country and inspire action” by others seems unrealistic, at best.

The thirty years since the end of the cold war have been a time of extraordinary change. Five profound transformations—globalization, China’s meteoric rise, the spread of terrorism, the dawn and epic growth of the digital age, and the retreat of democracy and international rise of populism—have been crammed into a brief period, together with the upheaval of the Iraq war and its aftermath and the 2008 global financial crisis, both sparked by American misjudgment. Even if Trump had never appeared on the scene, this would have forced Washington to finally confront the need to rethink foreign policy assumptions made in the aftermath of World War II that had become thoroughly out of date. Americans want fresh thinking about how much of an international burden the US should shoulder if it also wants to meet its domestic needs, protect its security interests, and sustain the values it cares about.

There is, in short, no going back to the status quo ante Trump. Moreover, if he is not reelected in 2020, Trump will leave behind seriously weakened international institutions and threats to global stability that will demand urgent action. Notwithstanding the Democratic candidates’ relative silence on foreign policy thus far, the next president will likely have to make international decisions of historic significance. It is important that they say more about how they would approach them before a nominee is chosen.

—January 16, 2020

-

1

See my “America’s Indefensible Defense Budget,” The New York Review, July 18, 2019. ↩

-

2

Biden received student deferments and was then exempted from military service because of teenage asthma; Sanders applied for conscientious objector status because of his opposition to the Vietnam War. ↩