For the German artists of the Renaissance, armor and weaponry held an extraordinary allure. One thinks of the great care lavished on armor in Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Knight, Death, and the Devil, which Dürer noted was based on the equipment of the German light cavalry of the day. He also made designs for the ornamentation of armor, three of which survive. And he made an etching featuring an elaborate piece of artillery in a landscape.

One thinks of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s panel painting of Saint Maurice in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was included in its recent exhibition “The Last Knight.” The black saint wears a silver armor (one refers to “an armor” or “a silver armor,” rather than to a “suit of armor”), which appears to have been commissioned by Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. It is magnificently gilded and encrusted with jewels, and it passed from imperial possession into a collection of reliquaries, where it was fitted out with an African head to represent the Roman legionary and Christian martyr—a life-size relic, illuminated in its sanctuary, the catalog of the exhibition tells us, by “thirteen main lamps and seven subsidiary ones.” This was in Magdeburg, where Saint Maurice was revered. But the silver armor was too valuable to survive very long; in 1541 it was melted down and its gems repurposed. Cranach’s depiction of it is suggestively correct in technical details, indicating that the painter had studied the armor close up.

One had to get such things right. Working for patrons and an audience who shared this armor obsession, the artist had to depict an object that made sense, just as the armorer had to create an armor that made sense. It had to fit the patron or the intended recipient (armor was often commissioned as a magnificent gift). And it had to work. Everything depended on the smoothly functioning design. But quite how the measurements and patterns for such armors were taken and transmitted from city to city seems not to be known.

If today you come across, say, a helmet that, because of some structural flaw, could never have functioned as a helmet, it is probably a relic of the nineteenth-century medieval armor revival—a helmet designed for display in some mock-baronial hall. A genuine piece of armor is an expression first and foremost of function, and only secondly of style. It should function like a space suit.

People get the idea that armor was never practical. It was far too heavy. You had to be raised onto your horse by a winch, and so forth. But this seems to be a popular misunderstanding, deriving from the declining years of personal armor. According to Walter J. Karcheski:

While a complete armor from the second half of the fifteenth century averaged some fifty to sixty pounds, this weight was well distributed over the body of the wearer, and posed little problem for a man who had been trained in the wearing and use of armor from an early age. Armorers recognized and took steps to deal with the problem of providing sufficient protection for the soldier while maintaining adequate ventilation and freedom of movement. It was only much later, in the second half of the sixteenth and throughout the seventeenth century, that the need for bulletproof armor caused the load to become virtually unbearable.1

This overlap between the development of firearms and the not yet declining use of armor made necessary a system of testing the strength of new pieces. You took, for example, a breastplate and fired a bullet at it, at close range. If the bullet ricocheted, leaving a dent (but not a hole) in the armor, that was good. Such a dent was called a “mark of proof.”

Just as a breastplate that had been dinged in this way was a good, reliable breastplate, so a lance that had been broken was a sign of a good day’s jousting. For a knight to have broken seven lances in a day would count as a memorable achievement, because the breaking of the lance was proof of the accuracy and effectiveness of the hit. Cranach, in a group of vivid woodcuts from the 1500s, shows us what one of these tournaments was like. The town square was packed with horses, riders, and lances, not to mention spectators, and the contestants fought, we are told, until one side had no rider capable of fighting left in the saddle. At this point, the participants regrouped, remounted, and fought each other again with swords, among the debris of broken lances.

Dangerous it sounds, and dangerous indeed it was, whether on the battlefield or in those “jousts of peace” and “jousts of war” with their carefully calibrated levels of risk. It was enough, at the Met, to compare the surviving lance heads for a joust of war, terminating in single sharpened points, with those for a joust of peace, in which the tip of the lance divides into a “coronel” of four blunt arms, intended to distribute the impact of a direct hit. One would not wish a single sharpened point, weighing between one and three pounds, to pierce any part of one’s personal defenses. But the peaceful coronel (which also weighs three pounds) would administer a severe shock to the system, especially as the helmet was fastened rigidly to the breastplate and backplate (known jointly as the cuirass) with bolts.

Advertisement

A matter of most exquisite calculation was the design and angle of the long horizontal eye slot, which gave the jousting helmet its frog-mouthed look. This eye slot was set in a way that obliged the rider to lean forward in the saddle in order to see at all. At the moment of impact, however, the experienced rider sat bolt upright. He could not, for that instant of combat, actually see his opponent, but the trade-off was that his eyes were protected. One would not want a three-pound prong of sharpened lance head to find its way into one’s helmet.

This terrifying practice of fighting blind was something the riders shared, on occasion, with their horses. One jousted either with or without a tilt—the barrier that separated the two riders. Jousting without a tilt was referred to as jousting “at large.” Each convention brought its own dangers. When jousting at large, the problem was that one’s horse might, naturally enough, seek to avoid the oncoming opponent. The solution was to equip the horse with a kind of shaffron (protective headpiece)2 that prevented it from seeing anything at all. A horse with a blind shaffron could be pointed in the right direction and might go at great speed. This increased, we are told, the danger of a head-on collision that might kill both the animals and their riders.

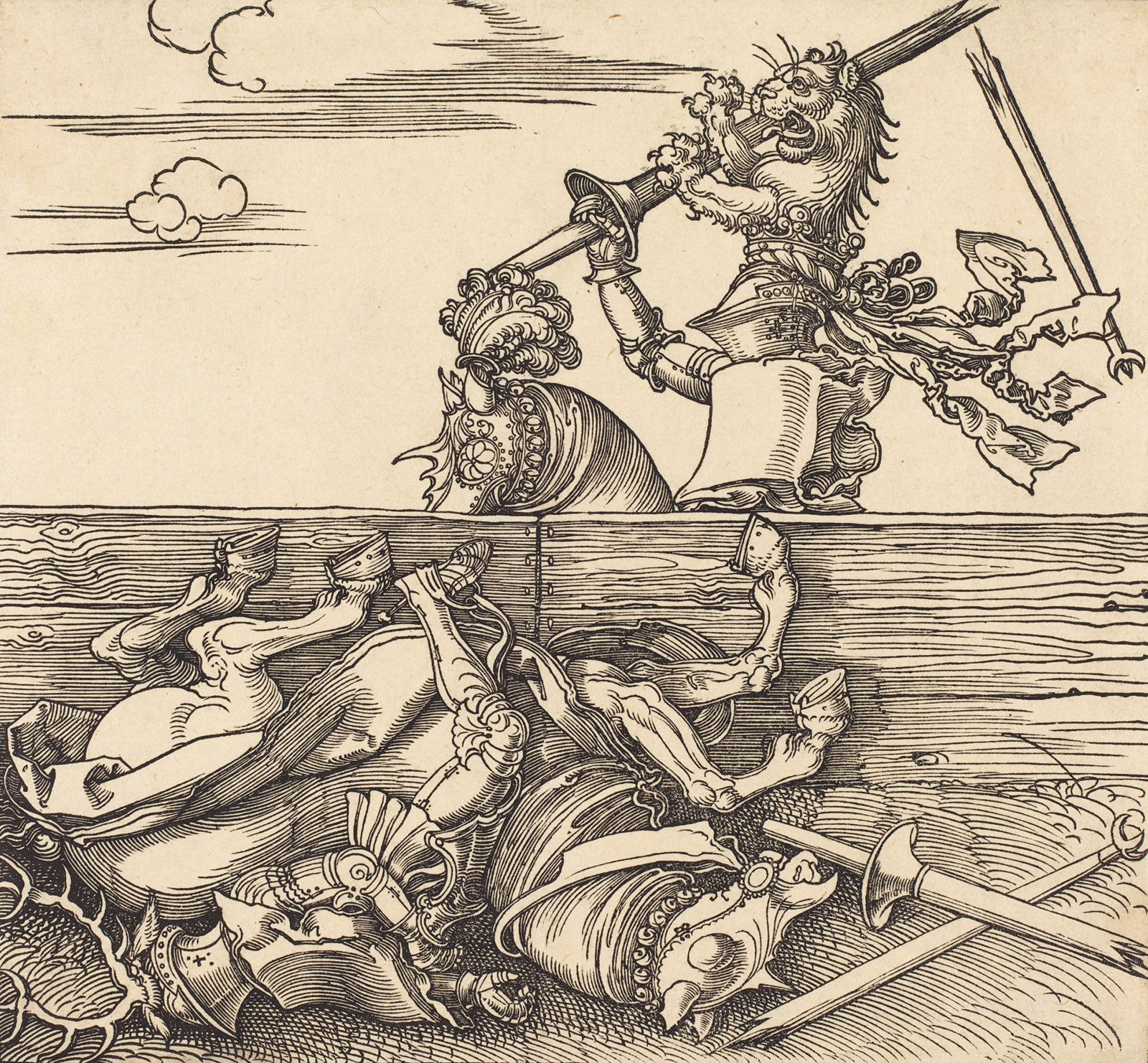

Jousting at large was the old, dangerous, German way. But jousting across a tilt (Italian-style) had its dangers too, especially when the purpose was to unseat one’s opponent. The two horsemen rode on either side of the tilt, in opposite directions. Their aim was either to break a lance or score some other palpable hit, or fully to unseat the other man. A particularly ferocious woodcut by Dürer shows a joust of peace in which both opponents have broken their lances, but the knight in the foreground has been unhorsed and trapped beneath his mount (see illustration on page 22). Obviously he is in mortal danger. One remembers that Maximilian’s first wife, Mary of Burgundy, died in a hunting accident after her horse rolled onto her and broke her spine. The knight in the background is Freydal, under which name Maximilian commemorated his own early heroic deeds. He holds his broken lance aloft, triumphant with his horse’s plume, his flying pennants, and his rampant lion crest.

Armor of the kind on display in “The Last Knight” is so splendid in conception, and so richly decorative, that it is possible to forget that it formed only one element of the magnificent display of the joust. There was also, for instance, the leather horse armor, surmounted by cloth of gold. Such trappings, we are told, were likely to be ruined during a contest, but that did not deter Maximilian, who, according to the catalog, “regularly spent more on his ornaments than on his equipment and horse.” Plumes were held in golden plume-holders set with diamonds and rubies and pearls. The laces of the bard were made of silk, with points of solid silver. When one considers how little secular goldsmith’s work in general survives from the fifteenth century, it is hardly surprising that so little of this specialist jewelry is left. The same is true for textiles. The humblest of objects, the padded “coif” designed to be worn inside the helmet during a joust of peace, fascinates with its rarity and with the answer it provides to the question: What made this armor wearable? It is a kind of inner helmet, fashioned out of linen, tow, hemp, leather, and iron. Dürer was interested enough to make a detailed drawing of one of these coifs.

The German artists shared their world with armorers, cutlers, smiths, and workers in all kinds of metal, and would long have been aware of the process by which a design could be etched or engraved on armor or weapons. Engraving relied on the artist’s skill with a burin, the fine instrument with which a line could be dug in the metal. Etching involved drawing onto the prepared waxed surface of the metal, then using acid to bite into the exposed surface areas. Both engraving and etching appear to have been in use since medieval times as ways of decorating the surface of metal. But nobody had yet thought of the possibility of printing from such ornamental metalwork.

Advertisement

It must have required a leap of the imagination. The dominant form of printmaking in Europe, since around 1400, had been the woodcut, taken, as the name implies, from a flat block of wood on which an image had been drawn. The artist cut away at the surface of the wood, wherever he did not want it to print. When the ink was applied to the block, only the uncut surface areas would be inked, which is why a woodcut is known as a kind of relief print.

With etchings and engravings, the opposite is true: only the lines or areas engraved or etched with acid into the metal plate will hold the ink, because the plate has been cleaned in such a way as to remove all other surface ink and dirt. The etcher’s press, with its wheel and blanket, is designed to ensure perfectly even pressure exerted on the paper and plate. Under this pressure, the slightly damp paper is forced into the grooves on the plate, where it, so to speak, finds out the ink.

Most likely, the items necessary for this new process, called intaglio printing, had been present in the workshops for decades before someone decided to pursue this counterintuitive technique—printing as it were from the groove rather than from the ridge. Who that someone was is not known. Dürer made etchings, but only half a dozen of them survive, as opposed to nearly a hundred engravings and over three hundred woodcuts. If he invented the printed etching (as was sometimes believed), he did not pursue it with great zeal.

Perhaps, though, the artists were a little slow to appreciate the revolutionary potential of the etching process. That might be because the early German etchers printed from iron plates, which had a tendency to rust, to the detriment of the image. In due course, however, they switched to copper, and the whole technology began to make better sense.

The missing link between the world of etched armor and that of the printed etching on paper appears to be the Augsburg-based artist Daniel Hopfer. The catalog of the Met’s exhibition “The Renaissance of Etching” shows us what appears to be the very first etching—alas not included in the show. Discovered recently in Bologna, it is signed prominently by Hopfer, can be dated to around 1493, and depicts the Battle of Thérouanne, with a large array of field guns in the foreground and a bloody encounter of cavalry and infantry in the middle distance.

What the Met was able to display in the exhibition—with a flourish—was a cuirass from its own collection, apparently decorated by Hopfer and dated sometime between 1510 and 1520. This indicates that there was at least one artist who was working simultaneously in the world of etching armor and making prints. Some of these prints are indeed designs for armor decoration, miniature in scale and intended as patterns for friezes and borders, for the channels of fluted armor, and for daggers and sheaths.

The catalog of “The Renaissance of Etching” makes the important point that “there is no evidence that the technique of etching was constricted by guilds or regulations anywhere during this formative period. Artists and craftsmen appear to have been free to learn the technique and apply it as they saw fit.” This goes some way to explain the feeling one gets when examining the work of the so-called Kleinmeister, or little masters, who grew up in Dürer’s shadow and made prints of anything that interested, impressed, or amused them—everything, that is, from the Passion of Jesus Christ to an orgy in an Anabaptist bathhouse. A monk engaged in alfresco sex with a nun. The hero Regulus nailed into a barrel by the Carthaginians. A sheath for a dagger on which a nude man and a woman wearing a chastity belt converse. A portrait of Martin Luther. A frieze of naked children fighting with bears.

Mostly this kind of work was executed on a miniature scale. One thinks of the goldsmith’s or silversmith’s art, which had such an appetite for decoration. But the practical uses of these ideas on paper would extend to larger objects as well—tiled stoves, cisterns or wall fountains, windows long since broken and crockery consigned to the midden. The artists were free to invent or to copy as they pleased. This was all about the transmission of ideas for ornament.

Some of the work is of very crude quality indeed—this was for the popular market. I have an earthenware cistern (of a kind that was hung on the wall and filled perhaps with rose water, for washing the hands before a meal) the front of which depicts, in low relief, a prisoner in the stocks, and beside him an angel at prayer. This turns out to be based on an image by Hans Sebald Beham: an allegory of Hope. In the etching, the word SPES (hope) explains all.

Beham’s etching is only an inch and a half high. The cistern is more than a foot tall. The man who made the cistern (he was called a Hafner, and this kind of pottery is known as Hafner ware) created a plaster press-mold for the front of the cistern. From this he took a first impression in clay. In copying the etching he omitted the inscription, which he perhaps could not understand.

I have read that the etchings of the Kleinmeister were, since they are usually so small, intended for the albums of collectors. More probably, they were small because copper had its price and because the artist did not need to make the image large in order to get his point across. The Hafner in my (imagined) example takes the little etching and pins it up above his workbench. By the time he has made his press-mold, constructed his crude cistern, and fired it, or fired several cisterns, the etching is probably a mess, spattered with slip, passed from hand to hand, in any case not treated as a collector would treat an etching. What was once common thus becomes rare.

Among the favorite subjects of the Kleinmeister were foot soldiers and their accompanying wives, and particularly standard-bearers with their fantasticated slashed doublets and enormous sleeves, and the flags that they carried on foot into battle. Another of Beham’s etchings shows such a standard-bearer in an awkward position, seemingly struggling with a snake between his legs. The catalog says that he “holds the phallic-shaped snake’s tail between his legs, he is bent in an unheroic pose, and he wears a foolish and insolent expression of a masturbating man.” It seems that only two copies of this print survive and that “it is conceivable that the etching enjoyed a certain popularity, and that its few surviving examples are the result of its having been frequently used as a frivolous wall decoration.”

This is a good point. The way prints were used determined their ability to survive to our day. The same applies to, say, early American wallpaper. If the wallpaper was stuck to the wall, in the manner of any conventional wallpaper, it was unlikely to survive the periodic redecoration of the house. If on the other hand some leftover scraps, as frequently happened, were used to line a bandbox, that wallpaper could well survive.

If an etching (frivolous or otherwise) was stuck to a wall in 1520, it’s not going to be there today. But if the crudest of medieval woodcuts were used to line, for instance, a small personal chest in 1450, there is a slim chance that they could have survived. When such chests are examined today, they turn out, sometimes, to be lined with unique examples of woodcut prints.

The genius of the German etching expressed itself in miniature and on the smaller scale. The genius of the woodcut recognized no limits to its ambition. Paper size presented no problem. The standard large folio sheet was roughly one and a half by two feet, but Dürer and Albrecht Altdorfer and their workshop got around this limitation when creating their Arch of Honor for Maximilian by printing a complex image and text on thirty-six sheets of paper, using (the “Last Knight” catalog says) “roughly 195 woodblocks.” The resulting work of art defies conventional display—it is over eleven by nine feet—and can hardly be read by the spectator, unless one were provided with stilts or some sort of hydraulic hoist.3

It is always, however, a pleasure to see one of these gigantic composite prints brought out of the print room and assembled for the benefit of the public. Only a handful of examples of this Arch of Honor survive. The one on view in “The Last Knight” belongs to the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It sets forth Maximilian’s “ancestry, his territories, his extended kinship, his predecessors as [Holy Roman] emperor, his deeds and accomplishments, his personal talents and interests, and thus his glory.” About that glory, the emperor was very clear. If he did not promulgate it, nobody else would:

He who during his life provides no remembrance for himself has no remembrance after his death and the same person is forgotten with the tolling of the bell, and therefore the money that I spend on remembrance is not lost; but the money that is spared on my remembrance, that is a suppression of my future remembrance, and what I do not accomplish during my life for my memory will not be made up for after my death, neither by thee nor others.

With this in mind, he ordered for his praise what was surely the biggest woodcut in the world.

This Issue

March 12, 2020

Foolish Questions

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe

-

1

Walter J. Karcheski Jr., Arms and Armor in the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), p. 25. ↩

-

2

There is great beauty, I think, to be found in these rare technical terms and obsolete usages. Karcheski’s useful Arms and Armor gives a full list of the components of a bard, or horse armor: “a shaffron for the head, a crinet for the neck, a peytral for the breast, flanchards for the area below the saddle, and a crupper for the hindquarters.” The catalog of “The Last Knight” offers an even more comprehensive glossary. ↩

-

3

High-resolution images of the Arch of Honor can be seen on the Met’s website at metmuseum.org. ↩