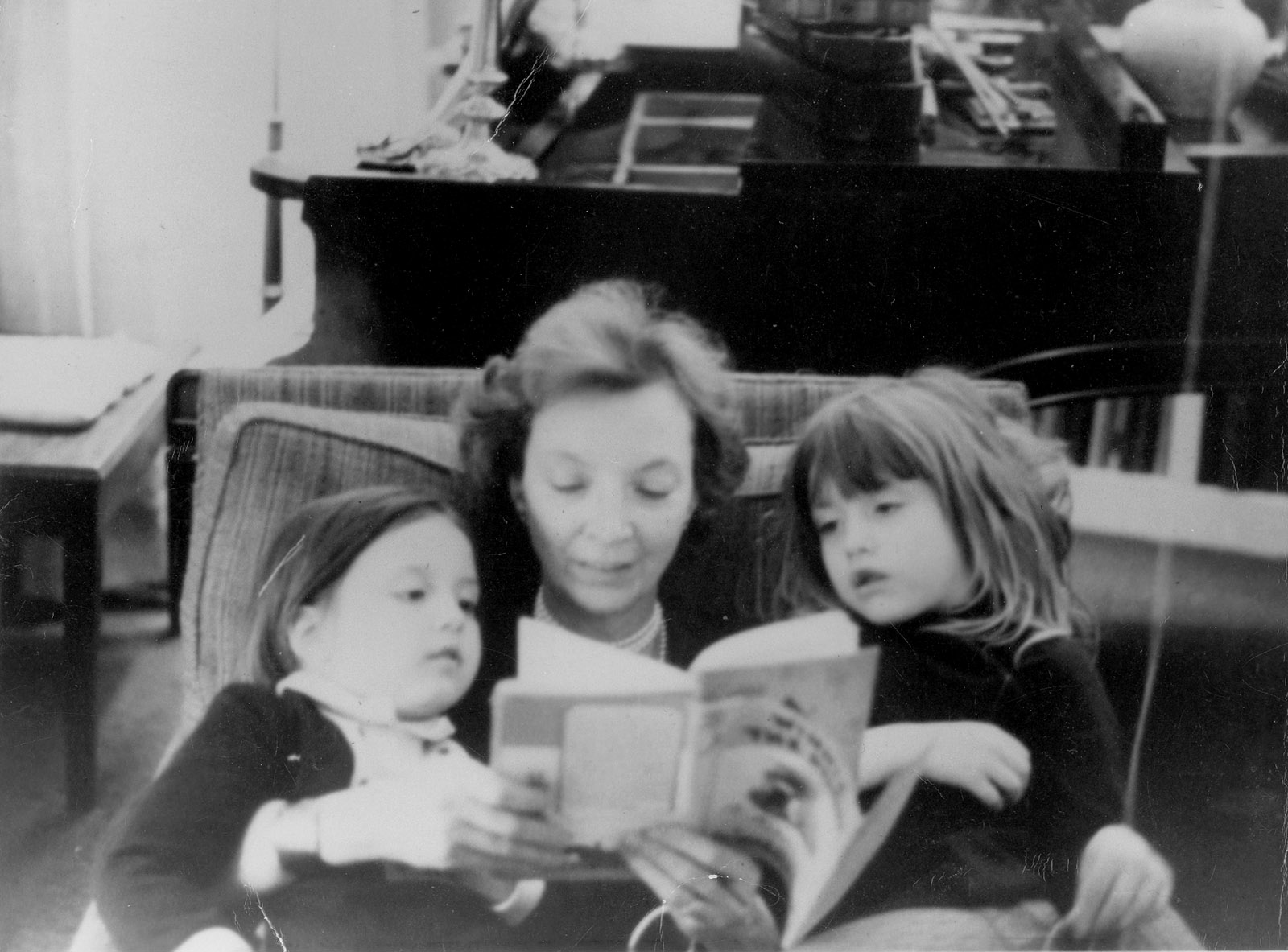

Madeleine L’Engle, a fixture in the lives of generations of American children and teenagers as the author of the classic novel A Wrinkle in Time, looked back on the 1950s as her “decade of failure.” After finding critical success in the 1940s with fiction for both young readers and adults, she had a run of persistent bad luck. One novel went unpublished; the next found a home only after years of effort. She and her husband had moved from New York City to run a general store in rural Connecticut, where many knew her simply as “the grocer’s wife.” After she received a rejection letter for another book on her fortieth birthday, in 1958, she wondered if she ought to give up writing and focus on being a housewife and mother to her three children: “Stop this foolishness and learn to make cherry pie,” she told herself. A practicing Christian who was active in the local Congregational church, she also had begun to struggle with her faith.

During the summer of 1959, L’Engle and her family embarked on a cross-country road trip. At night, after the children had gone to bed, she read books of higher math and physics by flashlight. As she recalled in “How Long Is a Book?,” a lecture from the early 1970s that is included in the second volume of the Library of America’s recent collection of her writings, she was seeking a light in the dark: “Not just to learn the various theories of the creation of the universe, the theories of relativity, of quantum [mechanics], but because in the writing of Sir James Jeans, of Einstein, Planck, I got a vision of a universe in which I could believe in God.” In the work of scientists and mathematicians, she continued, she found “a reverence for the beauty and pattern of the universe, for the mystery of the heavenly laws which argued much more convincingly to me of a loving creator than did the German theologians.” Driving through the Painted Desert in Arizona—an environment “as much out of this world as any of the planets” she later imagined in her fiction—she turned to the children and announced that she was going to write a new novel about three characters whose names had just come to her: Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Who, and Mrs Which. (L’Engle deliberately left off the period after the “Mrs” in their names, to emphasize that they were “extra-special as well as extra-terrestrial.”)

The book that L’Engle wrote after returning home was, of course, A Wrinkle in Time, which was published in 1962 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux after being rejected by at least two dozen publishers. It won the 1963 Newbery Medal and has become one of the best-loved, as well as best-selling, children’s books of the last fifty-plus years. Its heroine is Meg Murry, a gawky, socially awkward adolescent whose father, a physicist on a mysterious assignment for the government, has suddenly disappeared. Together with Charles Wallace, her preternaturally brilliant younger brother, and her schoolmate Calvin O’Keefe—a popular jock with whom she develops an unlikely romance—she embarks on an interplanetary adventure to save him. The trio are guided by the three Mrs Ws, who have the ability to “tesser,” or travel through space nearly instantaneously by creating a “wrinkle” in time. As Charles Wallace explains, “A straight line is not the shortest distance between two points.”

Studded with quotes not only from the Bible but also from Dante, Shakespeare, Descartes, and many other great humanists, Wrinkle is playful and intellectual, realistic and otherworldly. Absolute evil is embodied by the “ONE mind” of the planet Camazotz, where free will has been taken away and all the inhabitants are controlled by a central brain to which they must conform. On streets of identical houses, children bounce balls in perfect unison, and anyone who refuses to submit is brutally punished. “I am freedom from all responsibility,” the evil power croons to Charles Wallace, trying to take over his mind. But Meg recognizes that the consolation it offers is false. Freedom from responsibility, after all, is the fantasy of a world-wearied adult, not of a teenager, who longs for nothing more than to be trusted to make decisions for herself.

Wrinkle taught generations of readers—myself happily included—that there is reward, and even power, in being a misfit. “A heroine with glasses? Finally!” writes Sarah Bessey in her foreword to The Rock That Is Higher, one of L’Engle’s spiritual memoirs. At school, Meg suffers for being stubborn and independent-minded, but the qualities that make her a misfit are precisely the ones that serve her in facing down the evil on Camazotz.

Wrinkle and its sequels—A Wind in the Door (1973) and A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978), together with Many Waters (1986), which was published later and is stylistically quite different, but involves some of the same characters and takes place chronologically in between its two predecessors—constitute what L’Engle came to think of as the “First Kairos Quartet.” (The “Second Kairos Quartet,” centered on the adventures of Polyhymnia O’Keefe, Meg and Calvin’s oldest daughter, includes The Arm of the Starfish (1965), Dragons in the Waters (1976), A House Like a Lotus (1984), and An Acceptable Time (1989).) In contrast to chronos, or “clock time,” kairos is “real time,” although “what that is, nobody is quite sure,” L’Engle writes in a previously unpublished essay included in the first Library of America volume. “We experience glimpses of kairos,” she continues, “in moments of intense joy, when everything is more beautiful, clear, wondrous, than in ordinary every day experience.”

Advertisement

Young readers of the books, especially Wrinkle, are drawn to them by the way L’Engle combines her own rather fantastic version of science fiction with an emotionally accessible story: a girl’s fight to save her father, and later her brother, from the forces of evil. But those who return to the novels as adults, as many of us do after having children of our own, may be surprised to find them not exactly as we remembered. “Aare yyou llosingg ffaith?” the stuttering Mrs Which asks Meg at one point. Even more than the many theological memoirs L’Engle wrote later in life, in which she vigorously asserted her identity as a Christian artist, Wrinkle and its successors represent her spiritual autobiography. “I was trying first and foremost to tell a good story, because that is my business; I am a story teller and nothing else,” she later said. “But like it or not, I was also writing about a universe governed by the kind of loving God in which I hoped to believe.”

Children seem to have little trouble accepting A Wrinkle in Time as a science fiction novel, albeit an unconventional one featuring a prickly, plain teenage girl and a five-year-old boy who snacks on liverwurst-and-cream-cheese sandwiches. But adults attuned even remotely to religion will discover Christian symbolism on nearly every page. Even so, they may be taken aback by the revelation, in Leonard Marcus’s generous notes to the Library of America edition, of just how integral L’Engle’s religious references are to the novel. The first planet the children visit is called Uriel, which means “God is my light” in Hebrew and is the name of one of the four archangels recognized by the Episcopal Church. It orbits the imaginary star Malak, a version of the Hebrew word for angel. The creatures who live there sing a hymn based on a passage from Isaiah. And so on. The Mrs Ws, as Calvin will later try to explain to Meg’s surprised father, are “guardian angels” or even “Messengers of God…beyond human understanding.”

These religious trappings are pressed, sometimes awkwardly, into the service of L’Engle’s idiosyncratic brand of spirituality, which is layered with science and secular humanism and incorporates many personal quirks, including her use of the Hebrew-derived “El” as a name for God. At the root of all her writing is her vision of Christianity as a religion of love. Her God is not the fearsome (in her interpretation) God of the Old Testament but the forgiving, welcoming Jesus. “What I believe is so magnificent, so glorious, that it is beyond finite comprehension,” she writes in Penguins and Golden Calves, a book inspired by her journey, at age seventy-four, to Antarctica, where the purity of the landscape leads her to fulminate against the degradations she perceives in American culture—casual sex, pornography—and to reassert her credo:

To believe that the universe was created by a purposeful, benign Creator is one thing. To believe that this Creator took on human vesture, accepted death and mortality, was tempted, betrayed, broken, and all for love of us, defies reason. It is so wild that it terrifies some Christians who try to dogmatize their fear by lashing out at other Christians, because a tidy Christianity with all answers given is easier than one which reaches out to the wild wonder of God’s love, a love we don’t even have to earn.

It is through harnessing her own power to love that Meg must fight evil: love of her father (which needs only the slightest shift to be read as love of the Father) and love of her brother Charles Wallace, who is named for L’Engle’s own father, Charles Wadsworth Camp, and her father-in-law, Wallace Collin Franklin, to whom Wrinkle is jointly dedicated. The book is, essentially, a paean to fathers and children.

Wrinkle has been embraced by evangelical Christians as “a book written about a universe created by a power of love, and entered into by Very God El-self,” L’Engle writes in The Rock That Is Higher, in which she credits her recovery from a nearly fatal car accident in 1991 to her faith. But what famously got her in trouble with some fundamentalist Christians was not her unconventional terminology—the name “El,” she explains, comes from the Hebrew word “Elohim”—but her inclusion of secular heroes alongside religious figures in her personal pantheon. In a notorious passage, Mrs Whatsit asks the children to list some of the “fighters against evil” throughout history: Jesus naturally comes first, but they quickly add Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Bach, Beethoven, Gandhi, Buddha, Euclid, Copernicus, and Schweitzer. At an event in 1990 at Wheaton College in Illinois, an evangelical school to which L’Engle would donate all her papers and which she regarded as a spiritual home, she was heckled by visiting protesters who accused her of incorporating witchcraft into the book (it includes a character called the Happy Medium) and putting Jesus on the same level with Einstein and Buddha. L’Engle professed herself bewildered by the criticism. “I wrote A Wrinkle in Time as a hymn of praise to God, so I must let it stand as it is and not be fearful when it is misunderstood,” she wrote.

Advertisement

The sequels to Wrinkle are all essentially variations on its themes. In A Wind in the Door, the fight against evil takes place microscopically, within the cells of Charles Wallace, whose mitochondria (one of the building blocks of cells) are under attack. But the science fiction elements quickly fade into the background as religion dominates. Blajeny, Meg’s new guide on her quest to heal Charles Wallace, arrives with the traditional announcement of an angel—“Do not be afraid!”—and is accompanied by a creature he calls a cherubim. (Yes, it’s singular.) Marcus notes that the character could be named for “the Russian saint Basil the Blessed, also called Vassily Blajenny, or Basil ‘the fool for Christ.’”

The evil that must be fought here is nihilism, represented by the Echthroi, a word for enemy that comes from Greek versions of the Bible. They seek to “X,” or turn to nothingness, whatever they come into contact with; for reasons we aren’t told, they have chosen Charles Wallace as their target. The book is heavily influenced by L’Engle’s reading about the “butterfly effect,” the term coined by the mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz to describe the potential impact of small weather-related changes in one area on conditions elsewhere. It is often understood more generally, in Marcus’s words, “as a metaphor for affirming the significance of seemingly inconsequential events”—such as the fluttering of a butterfly—“in the grand scheme of the cosmos.” Here and elsewhere, L’Engle invests the metaphor with a profound moral significance. “It is not always on the great or the important that the balance of the universe depends,” Blajeny says. Later, another character elaborates: “It is the pattern throughout Creation. One child, one man, can swing the balance.” This lesson feels very powerful to children, who are often told by the adults around them, either explicitly or implicitly, that their thoughts and actions aren’t important. In L’Engle’s world, even something as microscopic as a mitochondrion can have cosmic significance, and a child can save the universe.

L’Engle takes these ideas further in A Swiftly Tilting Planet, in which the Murry family’s Thanksgiving dinner is interrupted by a call from the White House to inform Mr. Murry that the South American dictator Mad Dog Branzillo is about to launch nuclear weapons: “One madman…can push a button and it will destroy civilization, and everything Mother and Father have worked for will go up in a mushroom cloud.” Calvin’s mother—now Meg’s disagreeable mother-in-law—recalls lines from “The Rune of St. Patrick,” an ancient prayer that she learned as a child, and teaches them to Charles Wallace, who summons a unicorn that allows him to mentally travel through time seeking the roots of fratricide in an effort to prevent the nuclear attack. (Lest the word “rune” raise suspicions of paganism, Marcus assures us that the prayer was composed “in preparation for converting the Irish High King Lóegaire and his subjects” to Christianity.) Charles Wallace’s challenge is to intervene as a particular pair of brothers and their descendants quarrel throughout history, transforming the fate of the world by disrupting the dictator’s lineage. These clashes, again and again, have to do with encounters between Native Americans and European Christians, specifically two Welsh princes who arrive in what is now America and fight over the native woman they both want to marry. The result is a family line of blue-eyed natives, some of whom will ultimately sail to South America, becoming the dictator’s ancestors.

Rereading Planet as an adult, I was surprised by the detail with which I was able to recall much of its intricate plot and the profound emotions it evoked. As L’Engle works her way further and further into the family saga, parts of Planet are deeply moving, especially a later section in which Charles Wallace vicariously experiences the sordid family life that helped transform Meg’s mother-in-law from a spirited teenager into a ruined, bitter old woman.

More difficult to accept, however, are the implications of the book’s moral lessons, which are likely to be a stumbling block for an adult who overlooked them as a child. Granted, this is a novel that appeared just over forty years ago, and it is unfair to apply today’s politics to a text that is anachronistic in many ways, not only politically. Still, even then it was preposterous to suggest that blue eyes, especially in a Native American person, are a sign of innate goodness. This idea was not an anomaly in L’Engle. In Dragons in the Waters, the second in the Polly O’Keefe series, a tribe of Indians in Venezuela have for centuries been waiting patiently for the return of “the Phair,” a white man who impregnated a native girl and abandoned her.

One could argue that it is not racial prejudice, precisely, that underlies these books, but Eurocentrism, which, at the time they were written, was experiencing its last gasp of social acceptability. I imagine L’Engle would have happily owned up to this charge. In A House Like a Lotus, the third of the Polly O’Keefe books, a group of characters attending an international literary retreat bond by singing “Silent Night” in their native languages. Even the twins Sandy and Dennys, the least intellectual members of the Murry family, think first of “Euclid and Pasteur and Tycho Brahe” when attempting to come up with examples of historical heroes. This takes place in Many Waters, the weirdest and least successful of Wrinkle’s sequels, in which the twins find themselves accidentally transported to the world just before the Flood, where they wrestle with both their knowledge that the earth is about to be destroyed and their joint attraction to a girl they meet there while trying to figure out how to get back home. (In a nicely turned pun that works even better now than it did thirty-five years ago, one of the biblical figures hears “United States” as “Nighted Place.”)

There’s a quality of snobbery to all this that L’Engle also would likely have acknowledged. “Being a snob isn’t necessarily a bad thing,” Polly’s friend Max, a wealthy widow who lives on a southern plantation, tells her in Lotus. “It can mean being unwilling to walk blindly through life instead of living it fully…. Being alive is a marvelous, precarious mystery, and few people appreciate it.” L’Engle’s fiction constitutes an education in a culture that she obviously loved deeply, a culture in which children can quote Robert Burns in the original Scots, in which spontaneously arriving guests already know their parts in madrigals and Bach chorales, in which people drink “consommé with a good dollop of sherry.” The pedagogy comes with its own good dollop of condescension—L’Engle’s implicit assumption that her readers will appreciate, and benefit from, her instruction. But there’s a moral dimension as well: good people have good taste, bad people do not. In The Arm of the Starfish, a luxury hotel owned by a villainous capitalist features garish murals of native people and a giant TV; the O’Keefe house, by contrast, is filled with books and shabby-chic furniture.

As a child whose parents didn’t sing in four-part harmony with weekend guests or name pets after Shakespeare characters, I gobbled all this up as if it were one of the family dinners that Meg’s mother manages to whip up over her Bunsen burner while working in her home laboratory. But looking back on it as an adult, I find L’Engle’s vision of the good life less aspirational than blatantly elitist and exclusionary. Those who appreciate and conform to American and European Christian culture are allowed into the inner circle; those who don’t—because they are working class, like Calvin’s mother, or because they are superficially concerned with money and appearance, like a whole host of other characters—are cast out. On some level I must have always been aware of the overwhelmingly WASP tinge to L’Engle’s world, but the more troubling aspects of it eluded me as a child. It is painful now to read the scene in A House Like a Lotus in which Polly, stranded in Athens, condemns the “junky gift shops” filled with “phony icons” and “sleazy clothes” clearly intended to attract tourists: “One souvenir shop had a sign reading, ‘Welcome, Hadassah,’ and was recommended by some Jewish Association.” In a book where Greek and Sanskrit words are didactically explained within the text, the reference, as well as the vagueness of its phrasing, feels gratuitous.

An equally discomfiting element of the later books is what happens to Meg. In Wrinkle she is a force of nature: a math genius, fierce in her love for her little brother, stubborn and uncompromising. “Stay angry, little Meg,” Mrs Whatsit urges her. “You will need all your anger now.” So it is a shock to discover, in the Second Kairos Quartet, that Meg has disappeared, replaced by Mrs. O’Keefe: a devoted wife who spends her days raising the couple’s seven (seven!) children, mending, and cooking, while Dr. O’Keefe, the man formerly known as Calvin, runs his own lab. “Mother’s a whiz at math; Daddy says she could get a doctorate with both hands tied behind her back, but she just laughs and says she can’t be bothered, it’s only a piece of paper,” Polly says at one point. “Mrs. O’Keefe knew a great deal about her husband’s work and had often assisted him,” one visitor assures us. L’Engle responded to her readers’ accusations of sexism by asserting that

if women are to be free to choose to pursue a career as well as marriage, they must also be free to choose the making of a home and the nurture of a family as their vocation; that was Meg’s choice, and a free one, and it was as creative a choice as if she had gone on to get a Ph.D. in quantum mechanics.

That is, indeed, a choice. But it couldn’t possibly be the choice of the Meg to whom we were introduced in Wrinkle, not unless she had a lobotomy. It’s utterly inconsistent with what we know of her character.

Did L’Engle have Meg choose family over career because of her guilt over having prioritized her own writing? As yet there exists no comprehensive biography of L’Engle, although a book by Abigail Santamaria is in the works.* Still, journalistic portrayals of her, as well as Listening for Madeleine, a book of interviews conducted with various people who knew her that came out a few years ago, have suggested that L’Engle’s depictions of motherhood in her novels were highly idealized, evoking the mother she wished she could be. And the knowledge that L’Engle’s husband, Hugh Franklin, was often rumored to have been unfaithful makes some of Calvin’s and Meg’s dialogue in Wrinkle more comprehensible. “You know it isn’t true, I know it isn’t true,” Calvin says to Meg about gossip that her father has abandoned her mother. “How anybody after one look at your mother could believe any man would leave her for another woman just shows how far jealousy will make people go.” It’s impossible to imagine a teenage boy talking like this. It seems more likely that L’Engle is talking to herself.

The problems with the books occur when L’Engle allows her agenda—religious, social, or personal—to displace her role as storyteller. One of her editors once said that her books reflected “her very deep faith…embedded in a great story with great characters.” But the reverse can also be true: the characters are embedded in the faith, which is the motor that drives Wrinkle’s less successful sequels. L’Engle herself rejected the idea that the two were separable. “Christian art?” she asks rhetorically in Walking on Water. “Art is art; painting is painting; music is music; a story is a story. If it’s bad art, it’s bad religion, no matter how pious the subject.” But Christianity, as L’Engle readily asserted, is at the heart of the way she thought of herself as an artist. These lines from Robert Frost’s poem “Two Tramps in Mud Time,” which are quoted frequently in The Arm of the Starfish, could be her artistic credo:

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation….

Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes,

Is the deed ever really done

For Heaven and the future’s sakes.

L’Engle was writing, always, for “Heaven and the future’s sakes.” In her acceptance speech when Wrinkle won the Newbery medal, she argued that fantasy and myth are a “universal language, the one and only language in the world that cuts across all barriers of time, place, race, and culture.” But while the battle of good against evil is indeed a universal trope, the way L’Engle formulates it is decidedly specific. “To be truly Christian,” she wrote, “means to see Christ everywhere, to know him as all in all.” Among other things, it means reading the Old Testament as a springboard to the New. “If the Flood had drowned everybody, if the earth hadn’t been repopulated, then Jesus would never have been born,” Dennys realizes in Many Waters, in which the purpose of the twins’ adventure seems to be shoring up their belief in the truth of the Bible. And it means continuously asserting that the Christian way is the truest way. While characters may profess admiration for Buddha or Einstein, there’s no question of where such figures rank in the moral hierarchy.

In “How Long Is a Book?,” her lecture about the genesis of Wrinkle, L’Engle said that she was “struggling through a period of agnosticism” when she conceived the novel. The greatest Christian memoirs, dating back to Augustine’s Confessions, all acknowledge doubt and wrestle with it. Strikingly, L’Engle’s books—fiction or nonfiction—do not. One would imagine that their author’s faith had never wavered. In fact, the only place in all L’Engle’s work that I found such an acknowledgment was in that same never-before-published lecture, in which she also expressed a poignant wish for “the kind of loving God in which I hoped to believe.”

Perhaps one reason why the later books are less successful as fiction is that L’Engle overcame her agnosticism; once her faith was stronger, she felt freer to indulge it. But I can’t help wondering if the opposite is in fact true, and the later books fail precisely because she didn’t convince herself. As she works harder and harder to fortify her own belief, the novels devolve into the same preachiness that characterizes her spiritual memoirs. The author of Wrinkle appears to have been fighting a battle that was to her just as dire as the struggle between good and evil she so obsessively depicts: the struggle for her own soul. It’s a pity she didn’t put more of that into her books.

This Issue

March 12, 2020

Foolish Questions

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe

-

*

The Moment of Tenderness, a new collection of L’Engle’s never-before-published stories, many of them juvenilia, will be issued by Grand Central in April. ↩