Two ladies on an outing to the Queens Museum one weekend last fall wander into “The Art of Rube Goldberg” exhibition. They enter casually and chuckle at a monitor playing a few moments from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times. A factory worker is immobilized in a complicated lunch-feeding contraption inspired by Rube Goldberg, a pal of Chaplin’s. It shovels some soup into his mouth, then short-circuits as it rams a whirring cob of corn up against his teeth, force-feeds him a couple of loose bolts, shoves a slice of cream pie into his dazed mug and then smears it with an automated napkin. Next, there’s a clip from a 1930 comedy, Soup to Nuts, written by Goldberg. (It includes a memorable antiburglar contraption but today is better known for featuring Larry, Moe, and Shemp before they became the Three Stooges.) The women glance at some of the original art on the walls as they drift out and one says, “Gosh, I never knew he was a cartoonist, too!”

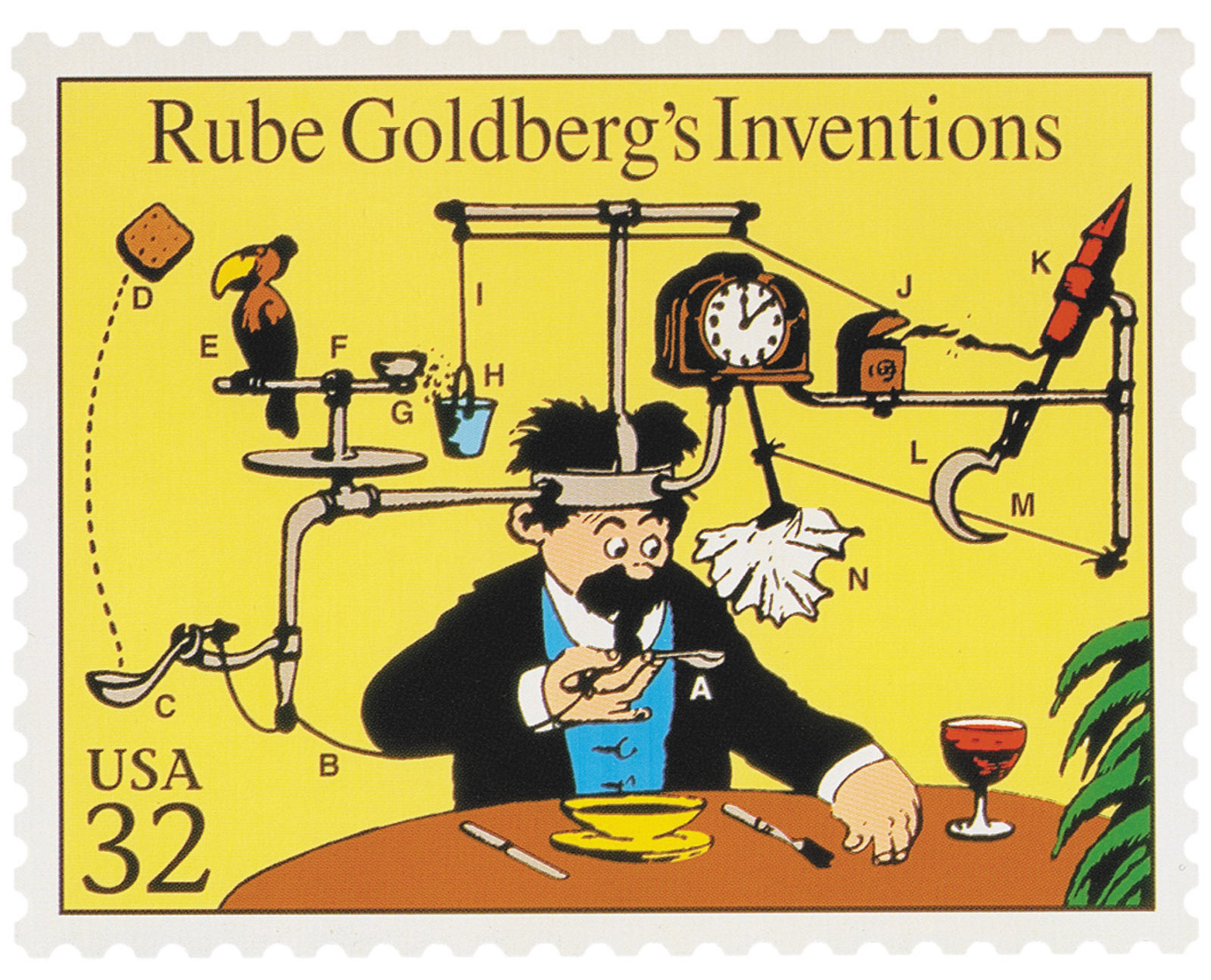

Being a cartoonist too was the price of immortality for a cartoonist so famous that he became an adjective in Merriam-Webster’s dictionary as early as 1931: “accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply.” The adjective still has currency, as in a recent Foreign Policy opinion piece that describes the electoral college as “that cockamamie Rube Goldberg mechanism that never quite worked as intended.” (It shows up often in discussions of government policy and single-payer-health-care math.)

Rube Goldberg was the Christopher Columbus of the screwball contraption, finding a way to get from point A to point B by traveling through all the other letters of the alphabet. And, like Columbus, a number of other intrepid explorers had gotten there first. At least two years before Goldberg, the renowned British illustrator and cartoonist Heath Robinson began publishing deadpan-droll tableaux that featured useless inventions, as did Denmark’s hidden treasure, cartoonist and humorist Storm Petersen. Both “Heath Robinson” and “Storm P.” were adjectivized in their own nation’s lexicons. None of this has anything to do with plagiarism; it’s a marker of the disorienting Machine Age these artists were born into, and of cartooning’s singular role as a Zeitgeist barometer.

Goldberg was born on July 4, 1883, to a Prussian-Jewish immigrant father who became a fixture in San Francisco Republican politics. Fearful that his son would become an artist, Max Goldberg insisted that Rube study to be an engineer at UC Berkeley. He graduated in 1904 to a job mapping out sewer mains for the city of San Francisco but bailed just four weeks later to become a sports cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle. Goldberg’s engineering background allowed his ingratiatingly lumpy cartoons to retain the diagrammatic clarity both comics and patent drawings demand. So “Father Was Right”!—to quote one of the many pre-Internet memes Goldberg generated in the more than sixty series he drew in his lifetime. Others include “No matter how thin you slice it, it’s still baloney,” “Mike and Ike they look alike!” (identical twins, one Irish and one Jewish), and his first big hit, “Foolish Questions,” from 1908 (as in Foolish Questions—No. 40,976: “Son, are you smoking that pipe again?” “No, Dad,” says the son sucking a pipe larger than his head, “this is a portable kitchenette and I’m frying a smelt for dinner”).

Goldberg is said to have produced about 50,000 drawings in his lifetime, and his inventions made up only a small part of his vast and mixed-up mix of features. He was himself a master of reinvention: in his early days a vaudeville performer, then an animator, song lyricist, radio personality, short story and essay writer for popular magazines, toastmaster, and star of his own TV show. His last long goodbye as a cartoonist was drawing political cartoons from 1939 to 1964, before he “retired” and became a sculptor until his death at eighty-seven in 1970. His editorial cartoons were drawn in the style of Herblock, but with regrettable anti–New Deal and occasional pro-McCarthy stances (perhaps shaped by Goldberg’s class interests—his cartoons had made him wealthy, he was married to the White Rose Tea heiress, and apparently he had inherited his father’s Republicanism; as I mentioned, “Father Was Right”!).

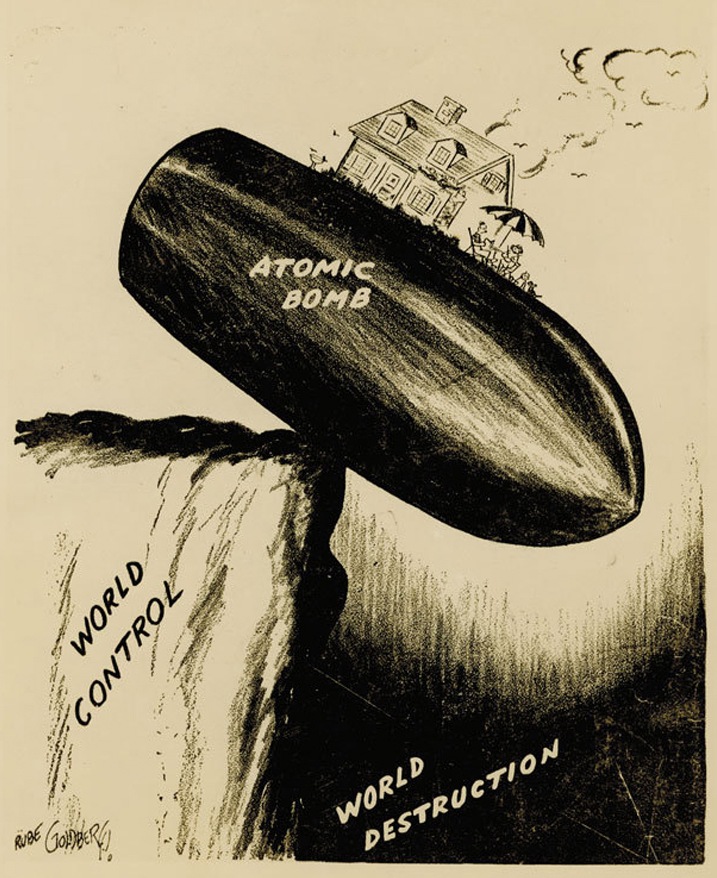

The traveling retrospective at the Queens Museum left out Goldberg’s more embarrassing political cartoons, and didn’t show even a tear-sheet of his powerful 1948 Pulitzer Prize–winning emblem of cold war anxiety, “Peace Today.” It depicts a suburban American family lounging on the lawn next to their two-story home, sitting atop a giant A-bomb that teeters over an abyss labeled “World Destruction.”

Advertisement

The exhibition supplemented the dozens of comic art originals on the walls with full broadsheet-size Sunday comic pages, vitrines over-stuffed with book covers, licensed games, postcards, buttons, and other ephemera, all to show the artist as an observer of social foibles with an acute sense of the absurd. The visitor was encouraged to linger over Goldberg’s deft yet humble grotesqueries and also to savor the rhythms of his copious prose. Back in the golden age of newspaper comics, there used to be space and time for written language.

The Art of Rube Goldberg, the definitive coffee table book from 2013 that served as the catalyst for this exhibit, provides over seven hundred well-selected images and several valuable historical and biographical essays. In the spirit of excess that the artist was known for, it even comes with a paper-engineered moving contraption operated by a pull-tab on its cover that will make the book enticing to any child near that coffee table. Whatever childhood pleasures Goldberg’s work may offer, as Adam Gopnik points out in his introduction,

there seems, to adult eyes, to be in [Goldberg’s] work some fatal, almost unconscious, commentary on the madness of science and the insanity of modern invention…. He doubtless would have laughed, or shaken his head in disbelief, if asked how his work related to Duchamp’s machine aesthetic, or to Dada—and yet every mark an artist makes takes place in a moment of time, and within a common frame of meaning.1

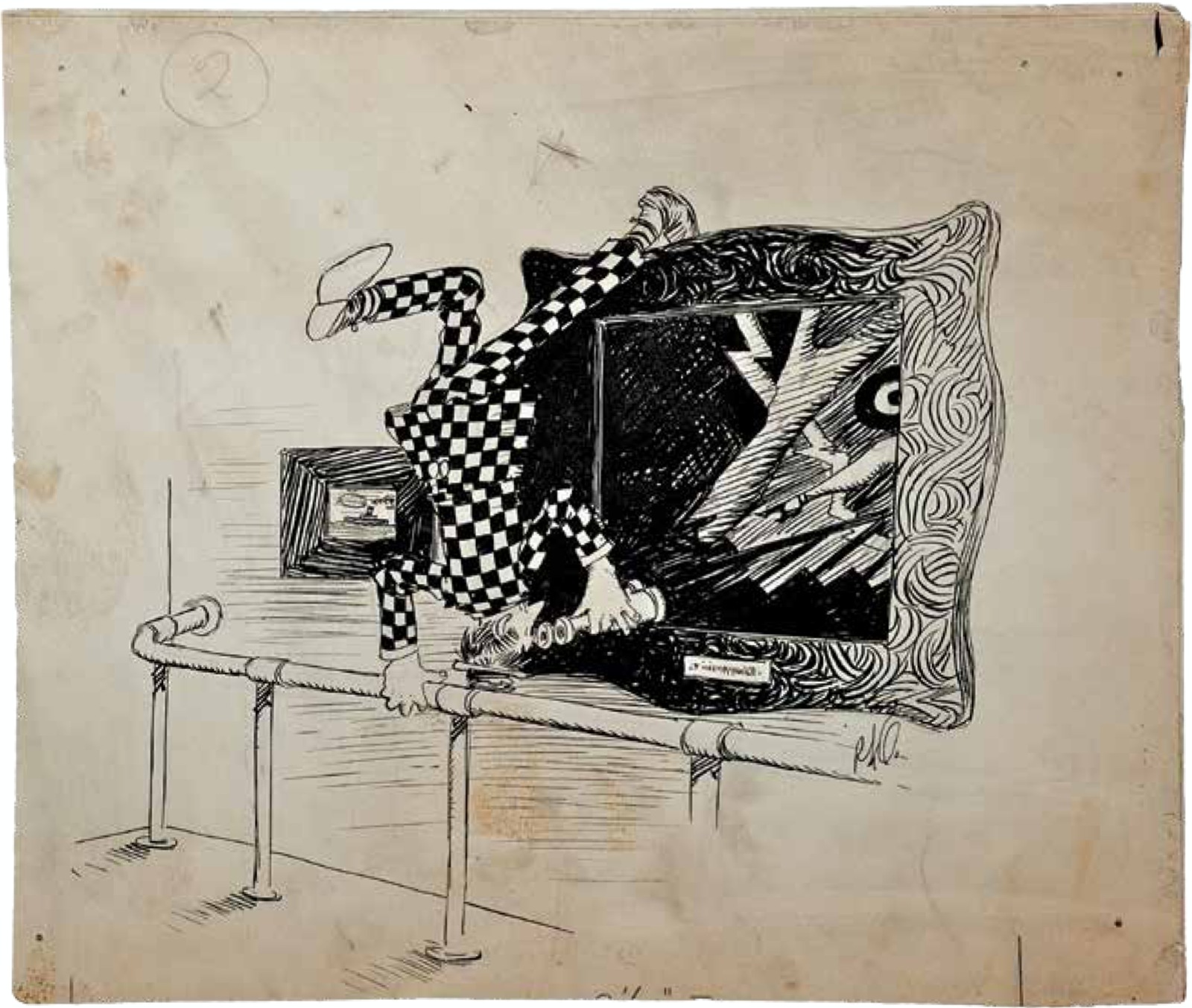

Duchamp and Man Ray embraced Goldberg as a fellow Dada traveler by putting one of his cartoons in their 1921 issue of New York Dada, but the feeling wasn’t exactly mutual. Like many American cartoonists of his day, Goldberg was dismissive of nonobjective art. As Peter Marzio, his biographer, wrote in 1973, “Rube believed that fine art was good only if it won public acceptance. Sales were Rube’s test of beauty.”2 Still, the cartoonist’s inventions showed up in MoMA’s landmark 1936 exhibit, “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism,” and were also part of its 1968 show “The Machine As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age.”

In 1970, two weeks before his death, a full retrospective of his work, entitled “Do It the Hard Way: Rube Goldberg and Modern Times,” was unveiled at the Smithsonian Institution. The show, according to Marzio, who cocurated the exhibition, was something of a blockbuster, with over two thousand guests attending the opening. Goldberg’s cartoons were also something of a “block buster” in the sense of opening up the redlined ghetto of “low” art, welcoming it into the hallowed precincts of High Culture. They were among the earliest examples of comic art ever to be displayed on art museum walls.

Over on the comics side of the collapsing high-low divide, Goldberg’s influence can be found in the work of generations of influential cartoonists, including Dr. Seuss, Harvey Kurtzman, and Robert Crumb—all of whom have now been exhibited in museums. In fact, with categories of every kind crumbling around us daily, seeing comic art on walls has become delightfully commonplace, though the celebration of Goldberg’s pioneering art in Queens was met with smaller crowds than he deserves. (The museum organizers tried to entice its audience, even having a well-intended if less-than-successful “Machine for Introducing an Exhibition” built to stand in front of the wall into the first gallery. The press of a button sets off a chain reaction involving an electric fan, a windmill, a die-cut Rube Goldberg drawing of a boot, a watering can, and three separate computer screens, each with simple animations of animals in a process that eventually unfurls a welcome banner. Mixing analog and digital technologies could have provoked thoughts about what the creator of useless complexity might have thought about life in our age of sleek electronics, but the whole device—barely a gizmo, let alone a contraption—looked minimalist and wan rather than deliriously tangible and maximalist, like the artist it was meant to introduce. The Saturday I visited, I pressed the green start button, and nothing happened. Then I noticed a sign on a stand nearby: “This work is temporarily out of order. We apologize for the inconvenience.”)

*

Foolish Question #25,743,000: “So are you somehow trying to say that Rube Goldberg was a serious Fine Artist???”

“No, you Boob! I’m pointing out to the uninitiated that Rube Goldberg was a fine Screwball Artist!”

*

Now that comics have put on long pants and started to strut around with the grownups by calling themselves graphic novels, it’s important to remember that comics have their roots in subversive joy and nonsense. For the first time in the history of the form, comics are beginning to have a history. Attractively designed collections of Little Nemo, Krazy Kat, Thimble Theater, Barnaby, Pogo, Peanuts, and so many more—all with intelligent historical appreciations—are finding their way into libraries.

Advertisement

Paul Tumey, the comics historian who co-edited The Art of Rube Goldberg book seven years ago, has recently put together a fascinating and eccentric addition to the expanding shelves of comics history.3 The future of comics is in the past, and Tumey does a heroic job of casting a fresh light on the hidden corners of that past in Screwball!: The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny. It’s a lavish picture book with over six hundred comics, drawings, and photos, many of which haven’t been seen since their twenty-four-hour life-spans in newspapers around a century ago. The book is a collection of well-researched short biographies of fifteen artists from the first half of the twentieth century, accompanied by generous helpings of their idiosyncratic cartoons. Goldberg—whose name schoolchildren learn when their STEM studies bump into chain reactions—is the perfect front man to beckon you toward the other less celebrated newspaper cartoonists who worked in the screwball vein that Tumey explores.

Screwball is an elusive attitude in the language of laughs and, like pornography, it’s hard to define but easy to recognize. Tumey prowls for common denominators and trails of influence that connect these odd ducks and their droppings. But the closer one looks, the less they seem to have in common. Virtually all the earliest newspaper comics were designed to be funny, but not all the funnies were screwball. The book is a survey, not in the sense of a Comics 101 history course serving up a knowledgeable overview, but more like a deep exploratory mining dig that samples underground specimens to assay what’s of value. The project is hardly arbitrary, but it doesn’t seem exactly definitive, either. It’s actually sort of, well, screwy—and it may just be that screwball is its own shortest definition.

One foot of the slippery screwball stretches back through vaudeville to commedia dell’arte with its stock situations and characters; the other foot strides forward toward Dada, surrealism, and the theater of the absurd—while the third foot of this ungainly creature remains firmly balanced on a banana peel. Screwball comics tend toward the manic, excessive, over-the-top, obsessive, irrational, anarchic, and grotesque; they can veer toward parody or satire, but at their core they are an assault on reason and its puny limitations. They wage a gleeful war on civilization and its discontents—armed mostly with water-pistols, stink bombs, and laughing gas.

The cinematic analogs of screwball comics would include the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, Olsen and Johnson’s Hellzapoppin, as well as the early animated shorts of the Fleischer brothers, Tex Avery, et al. Screwball comics have little to do with the more attended-to genre of romantic “screwball comedy”—movies like Howard Hawks’s Bringing Up Baby or Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night—except in their velocity. Screwball strips, designed for family newspapers, had even fewer hints of sex than those screwball romantic comedies, though their punchlines did elicit sublimated climaxes with the so-called straight man flying out of the last box, feet in the air.

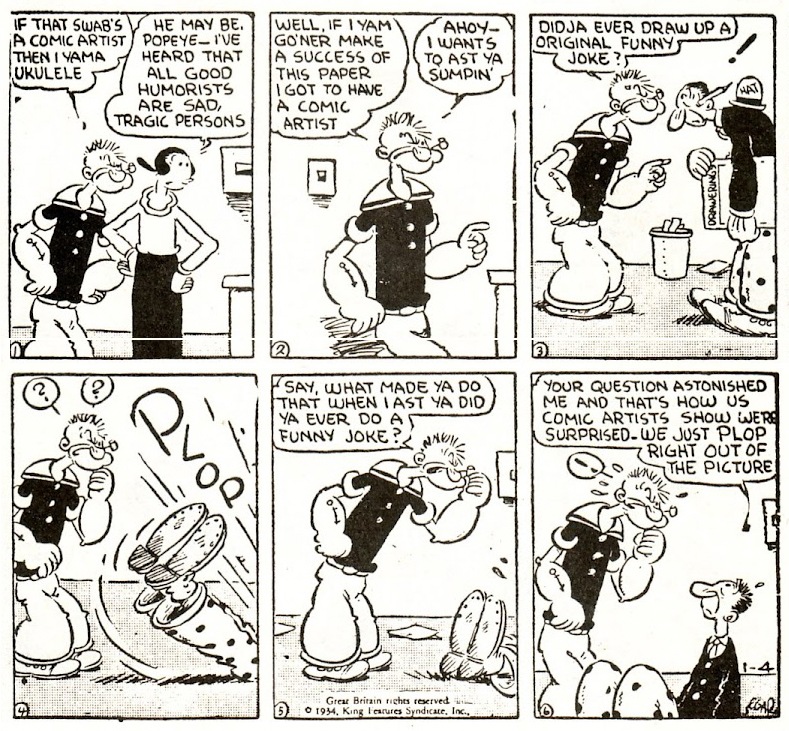

In Smokey Stover, Bill Holman’s essence-of-screwball fireman strip, rapid-fire puns rage through all the panels like kindling for a four-alarm newsprint conflagration. “Plop-take” feet sail out of their shoes, revealing toes that poke through sock holes; bowties pop off shirt collars while mustaches, hairpieces, eyeglasses, false teeth, and even ears explode clear off of heads. Another symptom of this approach—rechanneled id erupting in the release of a belly laugh—is what Tumey dubs “the screwball spin,” a blurry mandala of repeating heads and limbs that form a proto-Futurist pinwheel of frenzied slapstick action. It was, for example, how Elzie Segar drew Popeye pummeling an adversary in the ring—like a rapidly rotating phénakistiscope.

I can only tour you through a few of the giant screwballs spinning around in this treasure chest of salvaged newsprint, and will start as the book does, with Frederick Burr Opper. A founding father of the funnies, he’s credited with making speech balloons a regular part of the comics’ formal vocabulary. He was already a seasoned and highly regarded artist of forty-one by the time he was recruited by William Randolph Hearst’s Journal in 1899 as a big gun in the epic newspaper war between Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer.

Pulitzer had developed a high-speed four-color newspaper press, hoping to bring the great art of the ages to his masses. When he found that the imprecise, out-of-register printing made the Old Masters look like blurry Impressionists, he settled on a comics supplement with black outlines containing flat colors. The funnies became a major weapon in the battle for circulation—and Hearst soon set up his own color supplement, announcing it as “eight pages of iridescent polychromous effulgence that makes the rainbow look like a lead pipe!”

Opper, a formidable draftsman, had become a star in Puck, the color-lithographed, Progressive Era satirical weekly. Instead of bringing gravitas to Hearst’s paper, Opper remade himself as a king of comedy, working in a playful, casual mode. His first and longest-lived hit, Happy Hooligan, featured a hapless hobo with a tin can for a hat; his well-meaning but dimwitted attempts to be helpful brought swirls of multipanel havoc that often ended with a screwball spin of cops brandishing nightsticks and dragging our hero off to the slammer. He was a precursor of Chaplin’s tramp, Goldberg’s long-lived Boob McNutt, and, a half century later, another beautiful loser named Charlie Brown. Happy Hooligan is a genial version of the xenophobic caricatures of simian-featured Irish immigrants that Thomas Nast had angrily drawn for Harper’s Weekly and that Opper, following in Nast’s footsteps, had produced for Puck.

Ah, stereotypes! Cartoons are a visual language of simplification and exaggeration whose vocabulary was entirely premised on them. It’s as if the N-word was the only word in the dictionary to describe people of color, and even the poetry that comics can offer had to be written in this debased language. We humans are hard-wired toward stereotyping, and, alas, comics echo the way we think. It’s part of the medium’s danger and its power. Tumey’s collection of historical material comes with a trigger warning:

These comic strips were created in an earlier time and may include racial and other stereotypes; we reproduce them in historical context with the understanding that they reflect a thankfully bygone era.

He scrupulously tries to depict the work of the era accurately without grinding our eyeballs into an overdose of toxic images. Still, it’s hard to guide an uninitiated reader to distinguish between intentional insults and images that—considering the form and our nation’s history—are only ambiently offensive, reflecting the time in which they were made.

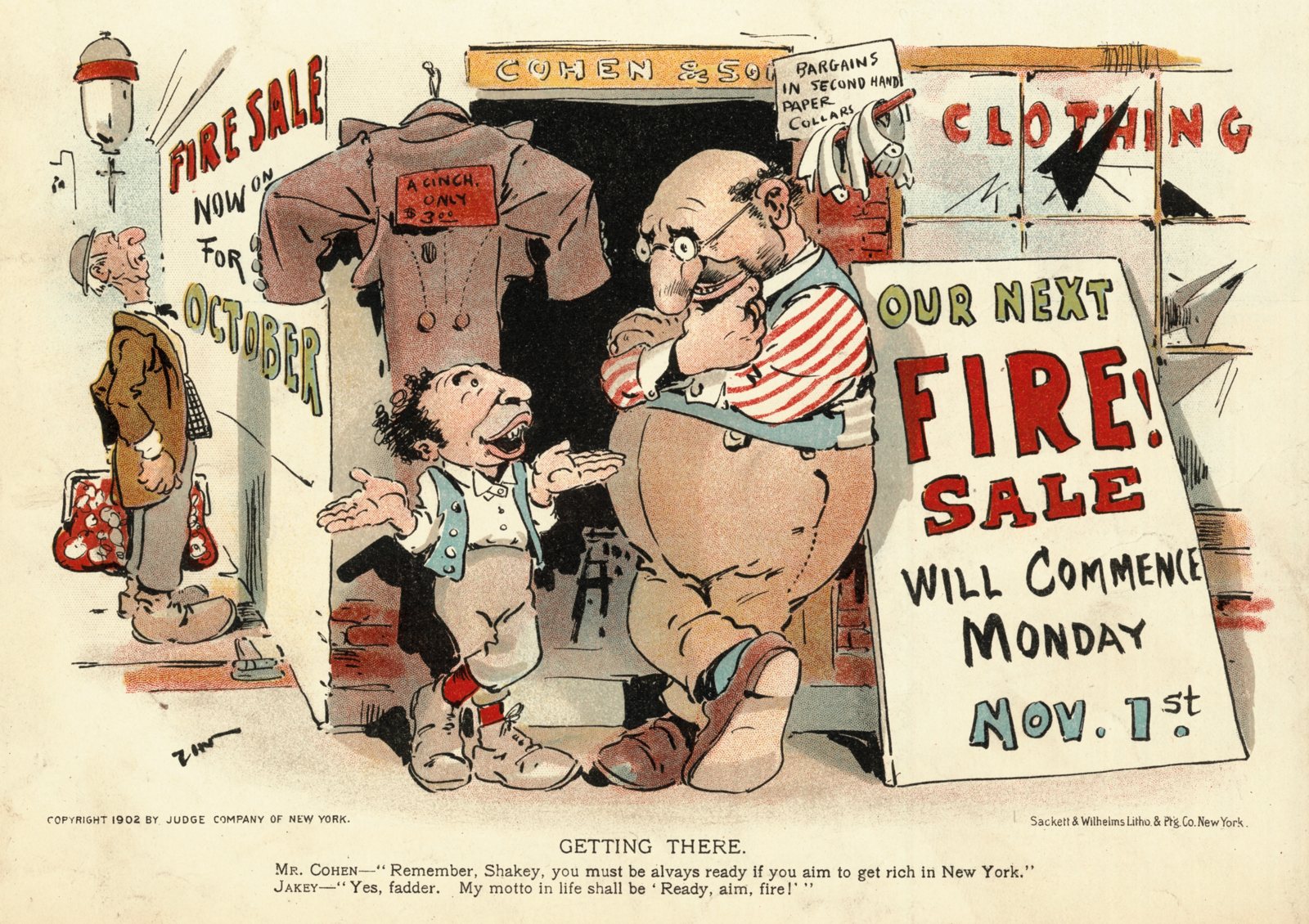

Which brings us to Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman, who was one of America’s most famous cartoonists at the turn of the twentieth century. A consummate graphic artist, Zim had an unfortunate predilection for the ethnic and racial themes that were especially popular at the time, and—though this material may represent only, say, 30 percent or so of his prolific output—he was brutally skillful at it. Zim once joked that he and his fellow cartoonists at Puck treated the various races and creeds that made up America with gloves, the kind boxers wear. It may explain why—despite the large influence he had on other cartoonists of his time—Zim has been more or less canceled from comics histories. Still, Rube Goldberg deeply admired Zim’s art and eulogized him as “the dean of grotesque pictorial humor.”

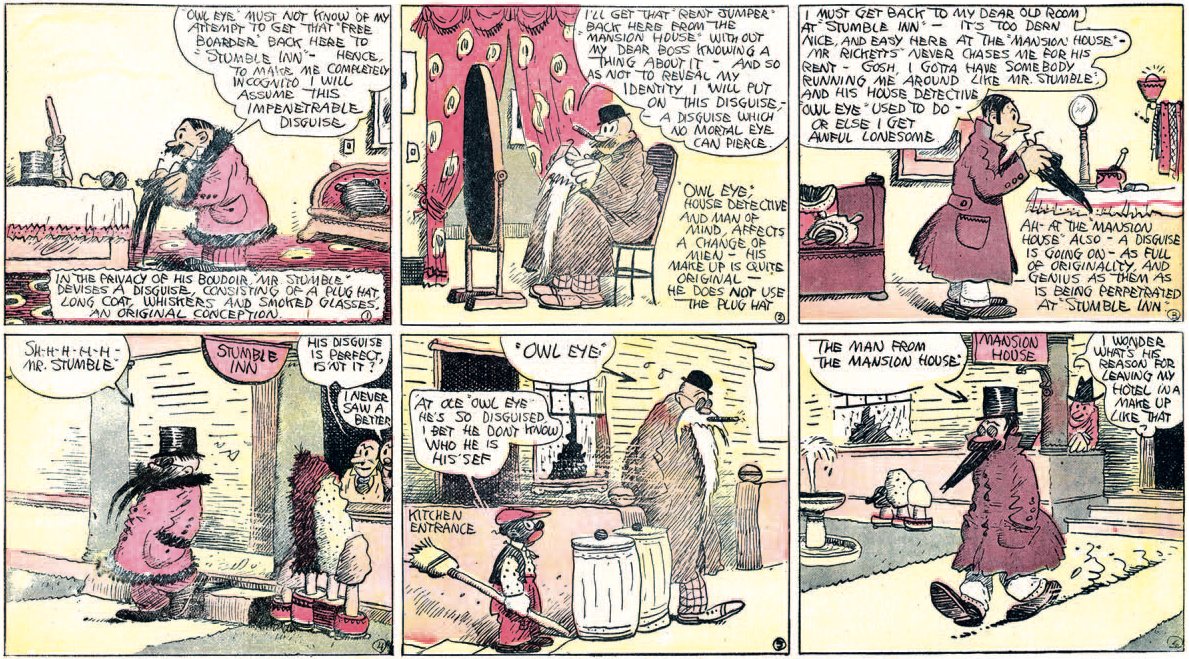

George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat, sits far from Zim on the screwball spectrum, on as high a throne as a comics canon can offer. Krazy Kat’s relentless vaudeville variations of a kat getting whacked by a mouse hurling a brick might make the work the ultimate expression of screwball, but its ethereal and gentle subtlety beckons the strip into a transcendent world of its own. Knowing that Krazy Kat is now widely available again, Tumey has chosen instead to offer a slice of Herriman’s far more obscure Stumble Inn. Krazy was getting an unenthusiastic response from most readers and most newspaper editors—Hearst often had to insist that his newspapers run it—so the cartoonist doubled his workload by simultaneously providing his syndicate with a more conventionally funny comic strip. Happily, he didn’t do conventional very well; Stumble Inn is a strip about a fleabag hotel that seems to anticipate John Cleese’s Fawlty Towers. It looks a bit like Mutt and Jeff if that strip had been drawn with the precision of a Renaissance master—some of the most breathtakingly beautiful cartooning I’ve ever seen.

Herriman was born in New Orleans in 1880. A Creole of color, he and his family left the city when he was ten years old and, as Michael Tisserand documents in his meticulous and revelatory biography, relocated to Los Angeles, where they passed for white for the rest of their lives.4 Reading Krazy Kat through that lens adds new layers of complexity to a strip about a black cat and the white mouse (pink on Sundays) who loathes him.5

The most poignant panel in Tumey’s book is in a wonderfully convoluted Stumble Inn sequence in which Mr. Stumble, Owl Eye (the hotel’s house detective), and a deadbeat boarder they’re now trying to lure back to their inn are each disguised in hats, long coats, and false beards. Soda Popp, the sweet young bellboy, with black face and large red lips (Herriman always drew his black humans according to the then standard cartoon physiognomic code), looks at the camouflaged Owl Eye and says, “’at ole ‘Owl Eye’ he’s so disguised I bet he dont know who he is his’sef.”

While Stumble Inn sits in a quiet and conventional suburb of Coconino County, in a dingy small town elsewhere on the comics pages we find Our Boarding House, established in 1921 by Gene Ahern. The homely daily panel orbits around the landlady’s lazy gasbag of a husband, Major Hoople, a hybrid of Falstaff, Munchausen, and W.C. Fields. He chases one hopeless get-rich-quick scheme after another and regales the other lodgers with tall tales about his big-game hunting or his heroism as a prisoner in the Boer War sneaking messages out hidden in alphabet soup.

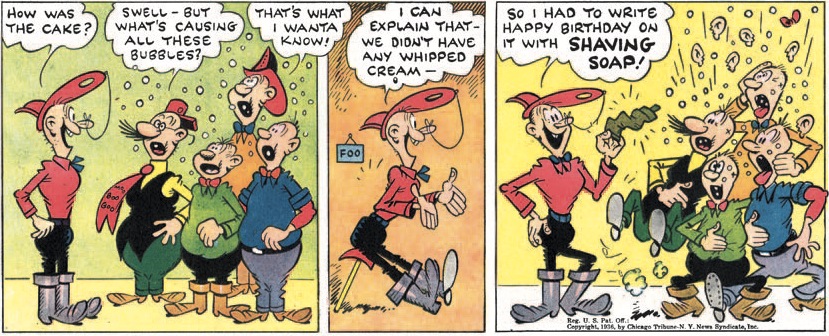

Syndicates back in the day often required their artists to provide “toppers” for their Sunday pages—small “throwaway” strips that could independently sit atop the main feature so papers could brag about having, say, thirty-two strips in their supplements rather than sixteen, or, even better, they could replace the feature with an ad. Comics always existed in the interstice between art and commerce, and Ahern turned the “minor” toppers into something simultaneously ridiculous and sublime. The Nut Bros., Ches and Wal, sat above Our Boarding House, breaking the fourth wall by offering their pun-laden old chestnuts with a self-aware wink and a surrealistic edge—goofy sight gags and costume changes from one panel to the next.

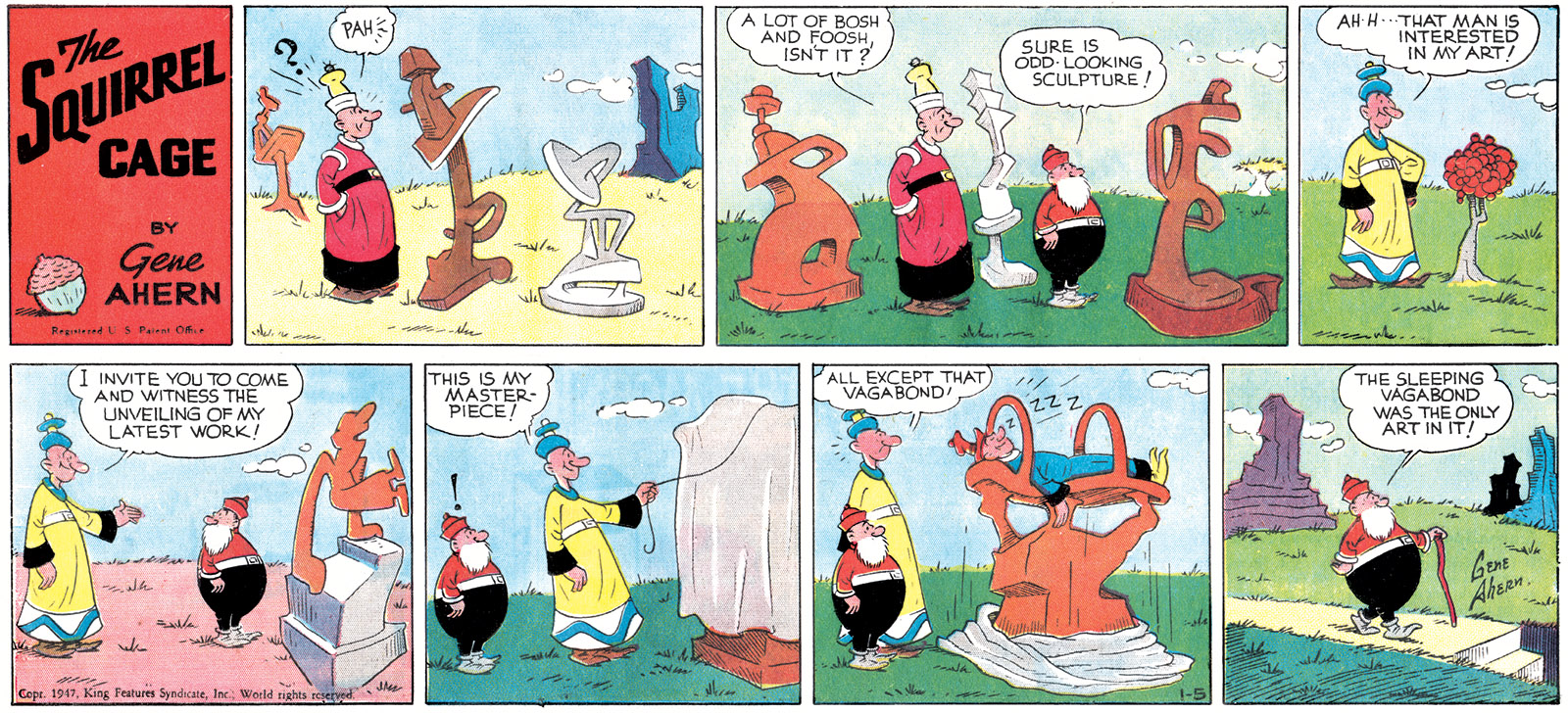

In 1936 Ahern moved to a larger syndicate at twice the pay but had to leave Major Hoople and the strip’s title behind. A near clone, Judge Puffle, now lived under a new logo, Room and Board. The Squirrel Cage, his topper for Room and Board, developed into one of the underappreciated hidden glories in the history of comics. It started as a direct continuation of The Nut Bros. but transformed into a strip that didn’t just have a surreal edge—it was surreal to its core.

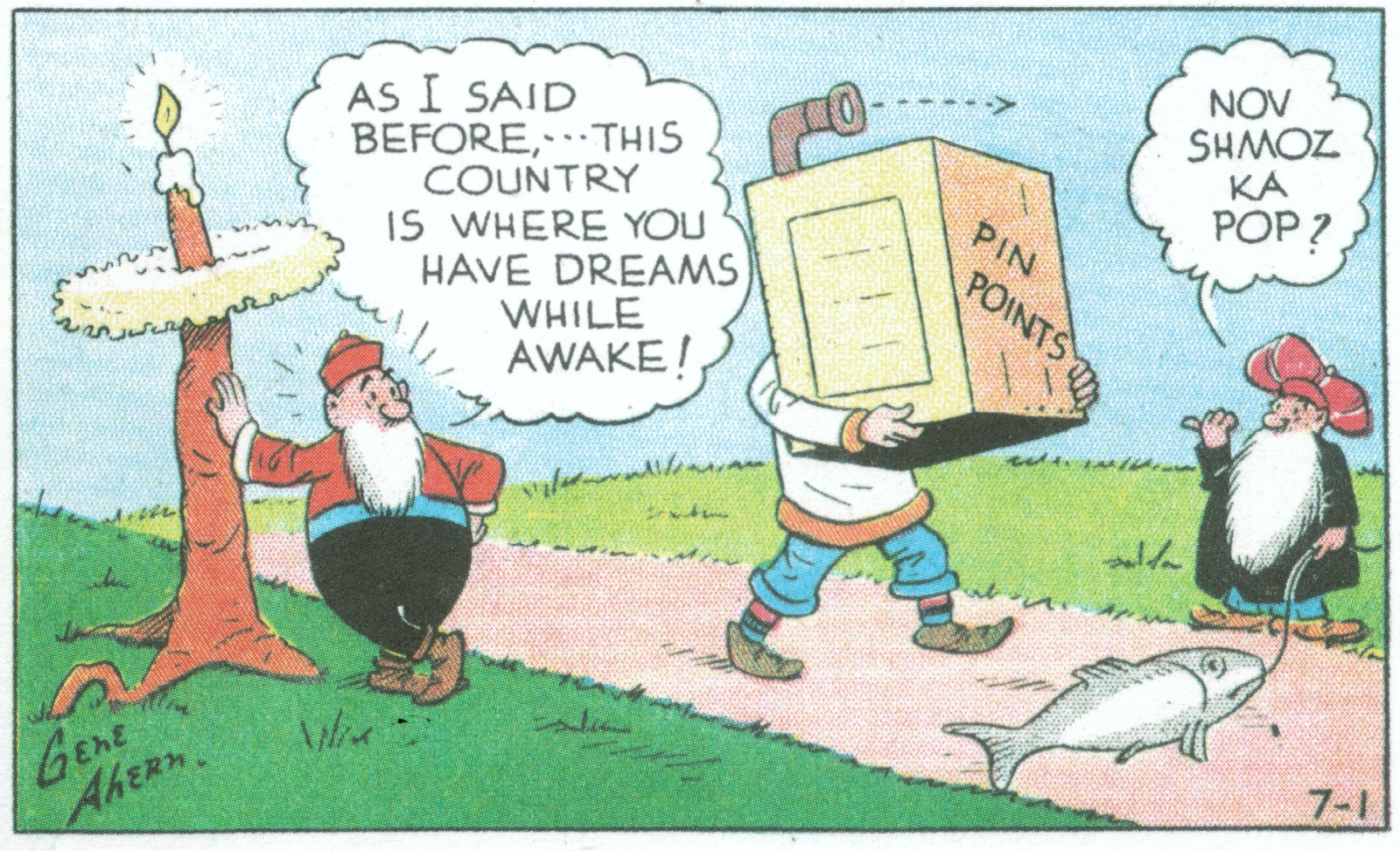

A bearded Little Hitchhiker—the direct model for R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural a generation later—started to pop up in the strip’s shifting landscapes with thumb extended, inscrutably asking: “Nov shmoz ka pop?” The vaguely Slavic-sounding gibberish was pretty much the only thing he ever said, and it became an unanswerable catchphrase, the kind that screwball strips were often able to wormhole into readers’ brains through satisfying repetition.

Ahern’s shifting backgrounds and props are less graceful than those in Krazy Kat. The characters, no matter how odd, seem to walk through their uncanny environment and impossible situations with the same resignation as if they were waiting for Godot. It all makes the irreal seem…real. The unearthly world of the top strip exists in a dialectical relationship to the drab boarding house in the strip below that contains the outsized fantasies of Judge Puffle.

Of all the wise guys6 gathered in Screwball!, Milt Gross is perhaps the essence of the idiom—cartooning distilled into precious drops of Banana Oil. (“Banana Oil,” for the uninitiated, was one of those aforementioned wormhole phrases, Gross’s equivalent of Rube Goldberg’s “Baloney!”) Gross was born to Russian-Jewish immigrants in 1895 and raised in the Bronx. In the early 1920s he created Banana Oil, among other strips, as well as an illustrated syndicated weekly newspaper column called Gross Exaggerations that crosscut conversations heard through the dumbwaiter of a small tenement building. Talk about finding one’s voice! It was written in Gross’s fractured Yiddishized English (Is diss a lengwitch? Dunt esk!) and gathered into a best-selling book called Nize Baby in 1926 before becoming a comic strip. His malapropisms and phonetic spelling ache to be read out loud for comprehension. His 1927 skirmish in the war against Christmas was a retelling of the Clement Clark Moore poem, “De Night in De Front from Chreesmas,” which starts:

’Twas de night befurr Chreesmas und hall troo de house

Not a critchure was slipping—not ivvin de souze,

Wot he leeved in de basement high-het like a Tsenator,

Tree gasses whooeezit—dot’s right—it’s de jenitor!

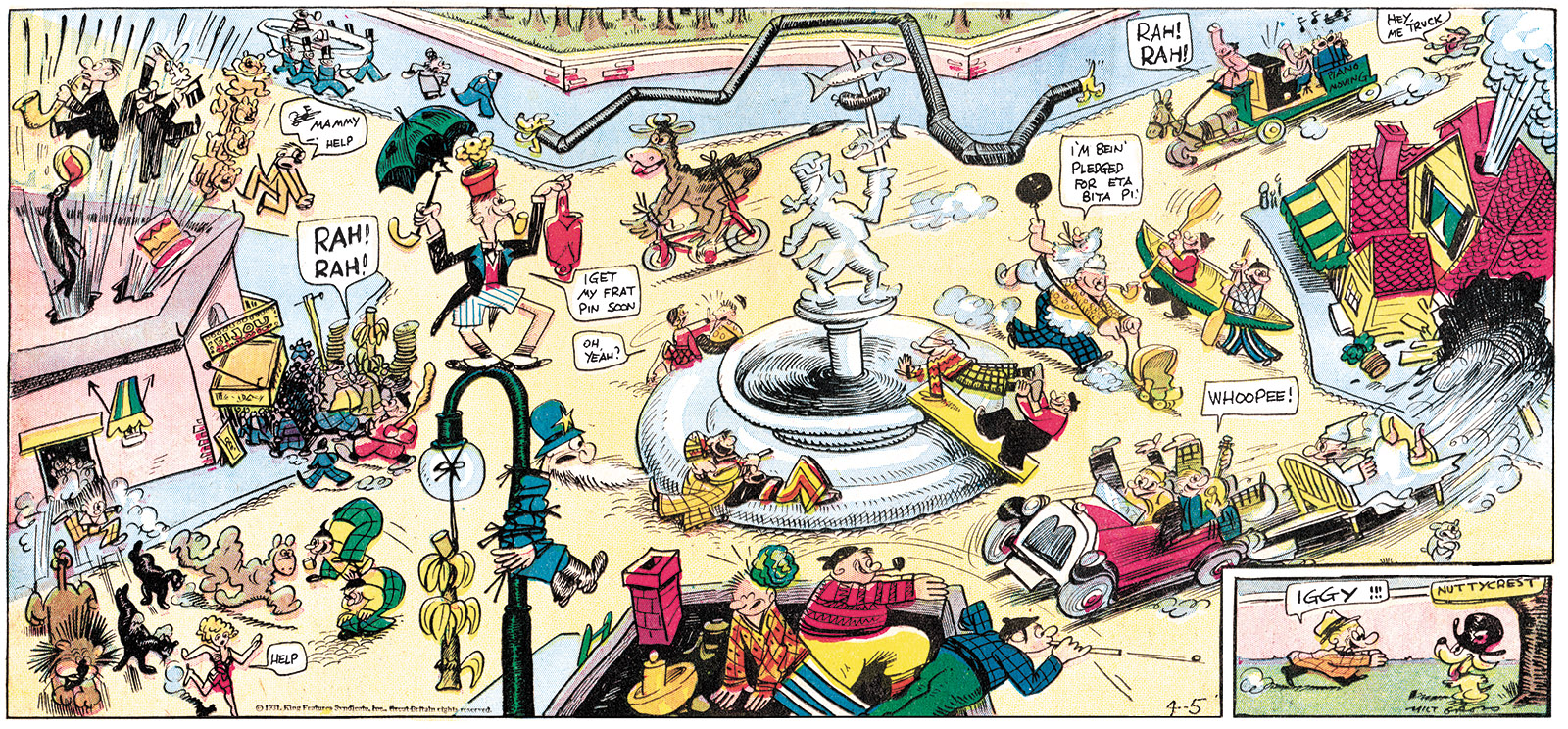

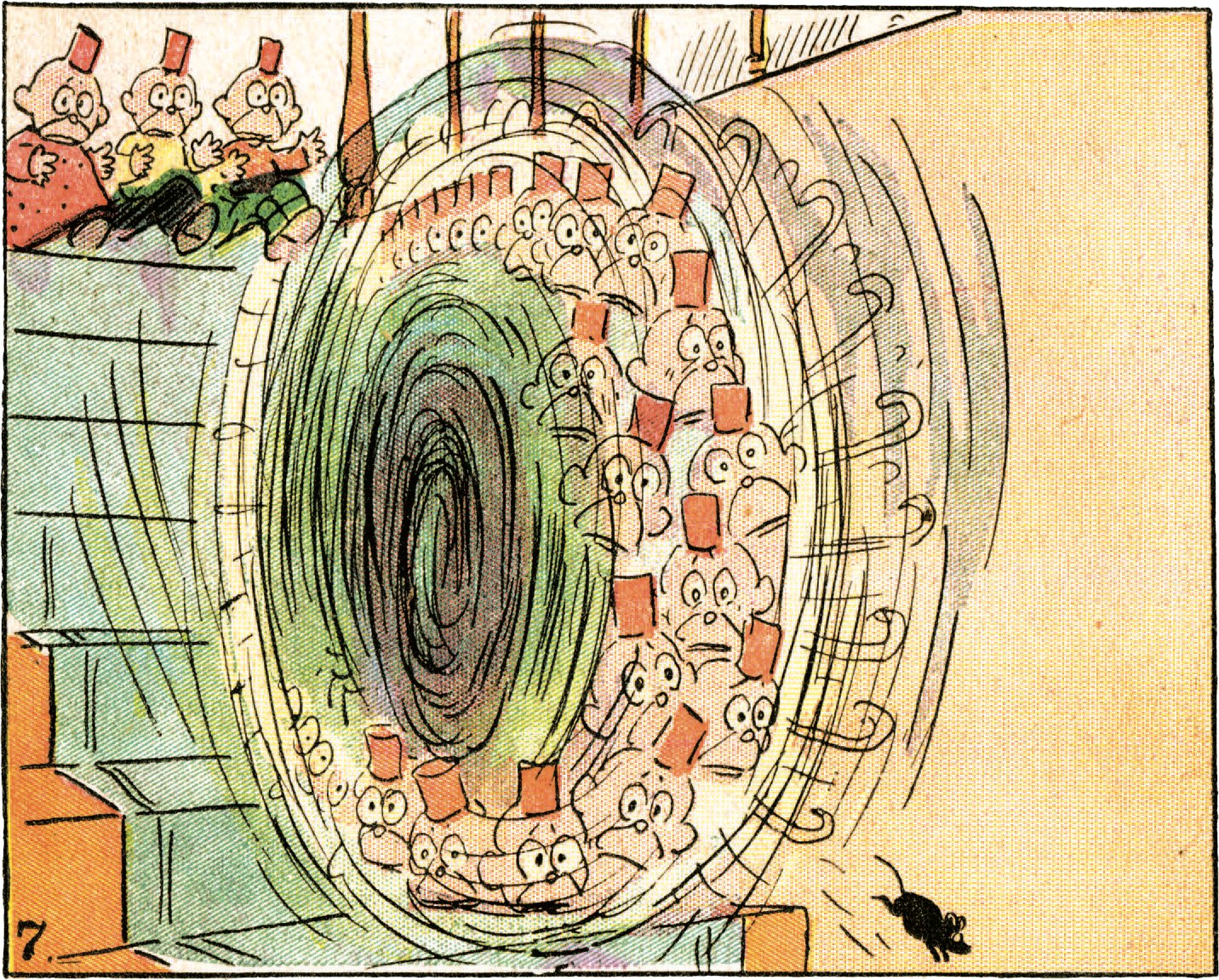

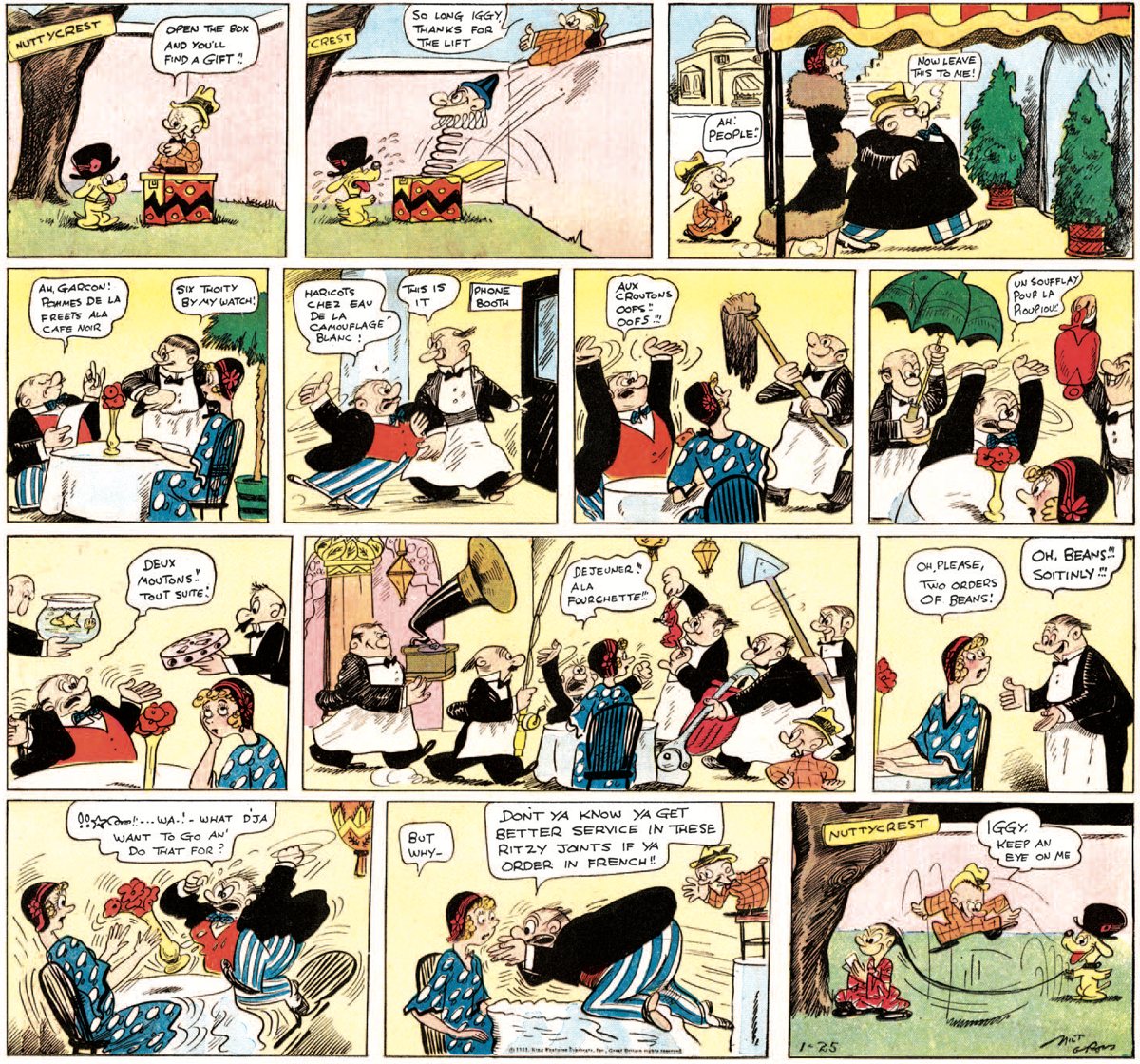

Gross was doubly gifted: an irresistibly risible writer and visually a comics genius. His cartoons are pure doodle: effortless and effervescent. The art looks like he was giggling uncontrollably while the cartoons just shpritzed out of his pen—and his laugh is infectious, bouncing off the page so you laugh too. Of his many creations, Count Screwloose of Tooloose, a Sunday page that launched in 1929, may be his screwiest. It reveals the thematic heart of all the screwball works in this book and beyond: The Count, a half-pint, sausage-nosed, cross-eyed resident of Nuttycrest Sanitarium, has an even smaller companion, a yellow dog named Iggy who wears a Napoleon hat. In each episode the Count devises a nutty new way to escape the institution and reenter the world outside its walls (see illustration on page 9). When he sees just how out of their minds the people out there are, he flees back to Nuttycrest, where his pup rapturously welcomes him home, as the Count exclaims, “Iggy, keep an eye on me.” Gross’s theme is an inverted way of expressing what Salvador Dalí famously said a few years later: “There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad.” Count Screwloose deploys Gross’s spontaneous and flexible pen line to search for the difference between the delusional and the rational.

The clearest expression of that search can be found in the subversive work of Harvey Kurtzman, the cartoonist who founded Mad. He is not included in Screwball!, since Tumey felt he had to limit himself to newspaper cartoons from the late nineteenth century through World War II to keep his project manageable—and Kurtzman’s Mad, originally a comic book launched in 1952, falls outside those parameters. But in a short afterword, Tumey writes, “Much of the material in Mad belongs to the lineage traced in this book. In fact, this book could be seen as the road to Mad.”

Indeed, the early Mad is the apotheosis of the aesthetic presented in Screwball! Kurtzman’s precisely timed comics look like a slower, more methodical and cerebral take on Gross’s mishegoss. The core tropes of the Smokey Stover take-no-prisoners chaos—its wacky signage that fills up all extra white space along with backgrounds that burst with sight gags—deeply informed the Mad that Kurtzman wrote and edited. Those “Easter eggs” in the backgrounds (what he and his lifelong collaborator, Bill Elder, called “chicken fat,” and my generation of underground cartoonists called “eyeball kicks”) are clear symptoms of a cartoonist irrepressibly interested in amusing himself as well as the reader.

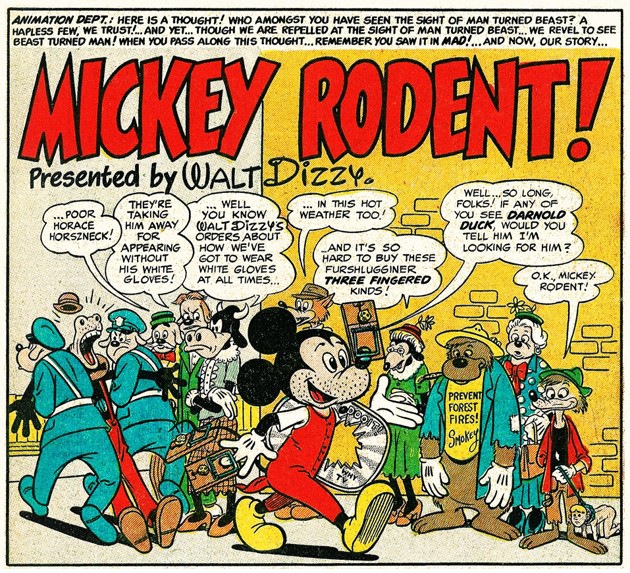

If the road to Mad was a loopy rollercoaster, the road from it has been riddled with potholes and has finally run into a wall. Mad was a revolutionary comic book. (Kurtzman transformed it into a magazine in 1954 and left in 1956 after an altercation with the publisher.) Its pointed parodies and satires, its anarchic questioning of authority, and its class-clown silliness shaped the generation that grew up to protest the Vietnam War. Kurtzman was concerned not only with being funny but with interrogating and deconstructing his subjects with a self-reflexive irony: he needed to locate something he could say that was true. (In Mad’s parody of Mickey Mouse, Kurtzman and Elder find something sinister in Disney’s Magic Kingdom—“Mickey Rodent” has stubble on his face and rat-traps on his nose and finger. In the splash panel, the Disney police are seen dragging off “Horace Horseneck” for not wearing the mandatory white gloves.) Reflecting on his work in 1977, Kurtzman said, “Truth is beautiful. What is false offends.”7 Even after Kurtzman left the magazine, Mad retained just enough of its promethean spark to wise up the generation or two after who found it. It has influenced American comedy—from Saturday Night Live to The Simpsons and Colbert’s Late Show—where the spark continues to glow.

But, alas, revolutions grow old and die. I was once told that Rudolph Giuliani grew up with a complete set of Mad. It may have been “fake news,” but the information crushed me: the vaccine that inoculated us against the suffocating 1950s was not a panacea.

This past October, the geriatric remains of Mad were put into cryonic deep freeze, to exist mostly as bimonthly specialty-shop reprints with a planned annual of new material to keep it in half-life in case any swell merchandising opportunities come along. The death knell was sounded last May, when Trump, hoping to tar the Democratic candidate Pete Buttigieg with one of his sophomoric and indelible zingers, announced that “Alfred E. Neuman cannot become president of the United States.”8 Asked about it, the thirty-seven-year-old mayor responded (either cannily or candidly, or both), “I’ll be honest, I had to Google that. I guess it’s just a generational thing. I didn’t get the reference.”

Yet the legacy of Mad is still with us. Trump is often referred to in the press as a “screwball,” but “screwball”—an ironic term of endearment, a synonym for “lovable eccentric”—just won’t do for a pathological, lying narcissist with dangerous sociopathic tendencies.

The existential threat facing screwball humor today comes from a “screwball” president who has weaponized postmodernism. Mad taught me to be skeptical of all mass media and to question reality (including my beloved Mad), but the lesson requires a belief that there might actually be something like consensual reality. Nonsense assumes there’s such a thing as sense and puts it in relief by denying reality’s power even if just for a moment.

*

Foolish Question #25,743,001: “So, is screwball humor dead?”

“Sorry, I can’t hear you, I have a banana in my ear.”

*

In early December, a banana duct-taped to a wall—Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian—sold for $120,000 at Art Basel in Miami. It made headlines all around the world for a minute, as either an immortal work of twenty-first-century art or an event destined to be more ephemeral than any of the pages in Screwball! A few days later a New York City–based performance artist pulled the banana off the wall and ate it, declaring the installation “very delicious.”

This caper brings to mind Goldberg’s “warning” at the front of Chasing the Blues, his first anthology of cartoons, in 1912:

I must burden you with a terrible confession. This is not a work of art!…

My artistic deficiencies remove me far from the sphere of Rembrandt and Michael Angelo. My ever-present realization of the material virtues of kidney stew and gorgonzola cheese has permanently destroyed whatever of the ethereal that may have been born within me…. A touch of art may nourish the soul, but a good laugh always aids the digestion.

*

Foolish Question #25,743,001.75: “So, can screwball comics ever be art?”

“No, you sap. Humor is the last thing one can take seriously—it’s priceless.”

This Issue

March 12, 2020

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe

-

1

Jennifer George, The Art of Rube Goldberg: (A) Inventive (B) Cartoon (C) Genius (Harry N. Abrams), p. 16. ↩

-

2

Peter C. Marzio, Rube Goldberg: His Life and Work (Harper and Row), p. 305. ↩

-

3

Full disclosure: the tribe of obsessive comics scholars interested in this sort of thing is a small one. Tumey and I became friends through a screwball blog that he started in 2012 to contemplate the subject. See screwballcomics.blogspot .com. ↩

-

4

Michael Tisserand, KRAZY: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White (Harper, 2015). ↩

-

5

Chris Ware wrote about Herriman and race for the NYR Daily: “To Walk in Beauty,” January 29, 2017. ↩

-

6

And in my best post–David Foster Wallace footnote mode, might I add what may not need saying at all: every one of these wise guys was a guy. While there have been many female screwballs in the history of the performing arts—Fanny Brice, Beatrice Lillie, Carole Lombard, and Gracie Allen come to mind, as do the two broads in Broad City—there don’t appear to have been any female screwballs at all in the overwhelmingly male domain of early-twentieth-century newspaper comics. I refer interested readers to historian and comics artist Trina Robbins’s several books devoted to casting light on women cartoonists and their accomplishments. ↩

-

7

Bill Schelly, Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America (Fantagraphics, 2015), p. ix. ↩

-

8

For those kiddies too young to know, the venerable “What—Me Worry?” gap-toothed grinning idiot served as Mad’s mascot from 1956 until its demise. ↩