One of the most celebrated attractions at Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial International Exhibition was the installation of Great Plains and Rocky Mountain wildlife in the Kansas-Colorado Building. Stereoscopic souvenir cards show a faux mountainside crammed like a Victorian what-not shelf with deer, goats, polecats, and raptors. A cougar is suspended mid-leap over the mouth of a cave, where a lady sits with a bird (species unidentifiable) in her lap. Not visible in the photographs, but noted in accounts, was a sign over the cave entrance announcing “Woman’s Work.”

The woman in question—the one whose work it was—was Martha Maxwell, and Mary Dartt’s 1879 book On the Plains, and Among the Peaks, or, How Mrs. Maxwell Made Her Natural History Collection opens in the voice of an incredulous visitor: “‘Woman’s work!’ What does that mean?… ‘Does that placard really mean to tell us a woman mounted all these animals?’… ‘Did she kill any…?’”1 The answer was, of course, a double-barreled “yes!”

Born in 1831, Maxwell was a former Midwest schoolmarm who had remade herself as an entrepreneurial gun-toting naturalist and progenitor of the natural history diorama (a subspecies of eastern screech owl is named for her). She evidently enjoyed an unusual array of talents, and one might assume that such nonconforming creative achievement had been preceded by angry repudiations of her womanly duties—feet stomped, suitors spurned, parents defied. One would be wrong. It was through adventures encountered while helping secure a house for her family that Maxwell, through a series of pragmatic steps, found her vocation. She had perseverance certainly, but more important, a nimble imagination—an invaluable asset when trying to get things done from a social position that generally demands constant accommodation to the needs of others. Woman’s work indeed.

Perseverance gets celebrated a lot, strategic tractability less so, but one of several important lessons conveyed by “Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work: The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection” was that adaptability is a lifesaver. Hosted by New York’s private Grolier Club, the nation’s preeminent bibliophilic society, this dense and discursive exhibition included some two hundred objects, mostly books, selected from the more than 16,000 accumulated by the collector and activist Lisa Baskin over the course of forty-five years. (The collection was acquired by the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University in 2015, and the exhibition was cocurated by Baskin, Naomi L. Nelson, and Lauren Reno; an earlier iteration took place last year at Duke’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library.) The exhibition’s compass was broad but not encyclopedic: everything on view came from Europe or North America and, with the exception of a thirteenth-century land grant, postdates the arrival of printing on paper in Europe and predates World War II. The history these things present is thus familiar in its broad strokes—the Renaissance, the Reformation, humanism, the Enlightenment, New World slavery, abolition, women’s suffrage, anarchism—but viewed through the lens of female agency, exotic in its particulars.

As might be expected, “Five Hundred Years” cheerfully banged the drum of female attainment, piling up proof that women have accomplished more, across multiple domains, than is commonly acknowledged. It showcased the great and the good—Sojourner Truth (a book and a demure portrait-photograph card marketed by Truth and bearing the legend “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance”); Susan B. Anthony (photo and letter); Marguerite de Navarre, the polymath sister of François I (a volume of verse for the common folk); as well as lesser-known foremothers: a pamphlet by the Reformation theologian Katharina Schütz Zell; a book by Laura Terracina, the most published Italian poet of the sixteenth century; a mathematical treatise by the eighteenth-century Milanese prodigy Maria Gaetana Agnesi. Betwixt and between flowed a cascade of firsts: the first book known to have been typeset by women (a 1478 edition of Lives of the Popes and Emperors produced by the Dominican nuns of San Jacopo di Ripoli in Florence); the first book published by an English colonist in America (Anne Bradstreet’s 1650 The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America); the first book published by an African-American of either sex (Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral from 1773).

All this is admirable and interesting, but the value of “Five Hundred Years” went beyond the parade of exceptional women who managed to keep up with the guys, doing the things guys do. It lay in the show’s interleaving of spectacular achievements and humble ones, like the oddly affecting, thimble-sized socks and hats knitted by Irish schoolgirls in 1850. Glued into a manual published for use in the National Female Schools, they tell us nothing about what these girls thought or felt. Were they proud of their skills? Bored by them? Yearning for a larger life? And what, in any case, would that have meant to a girl on an island that had been starving to death for three years? The woolens are mute. But they embody the endless making and making do, the honor and necessity of caring and creating at the heart of billions of unremarked lives. At the Grolier, it was easy to find yourself gently and subversively nudged into reconsidering the parameters of “achievement” altogether.

Advertisement

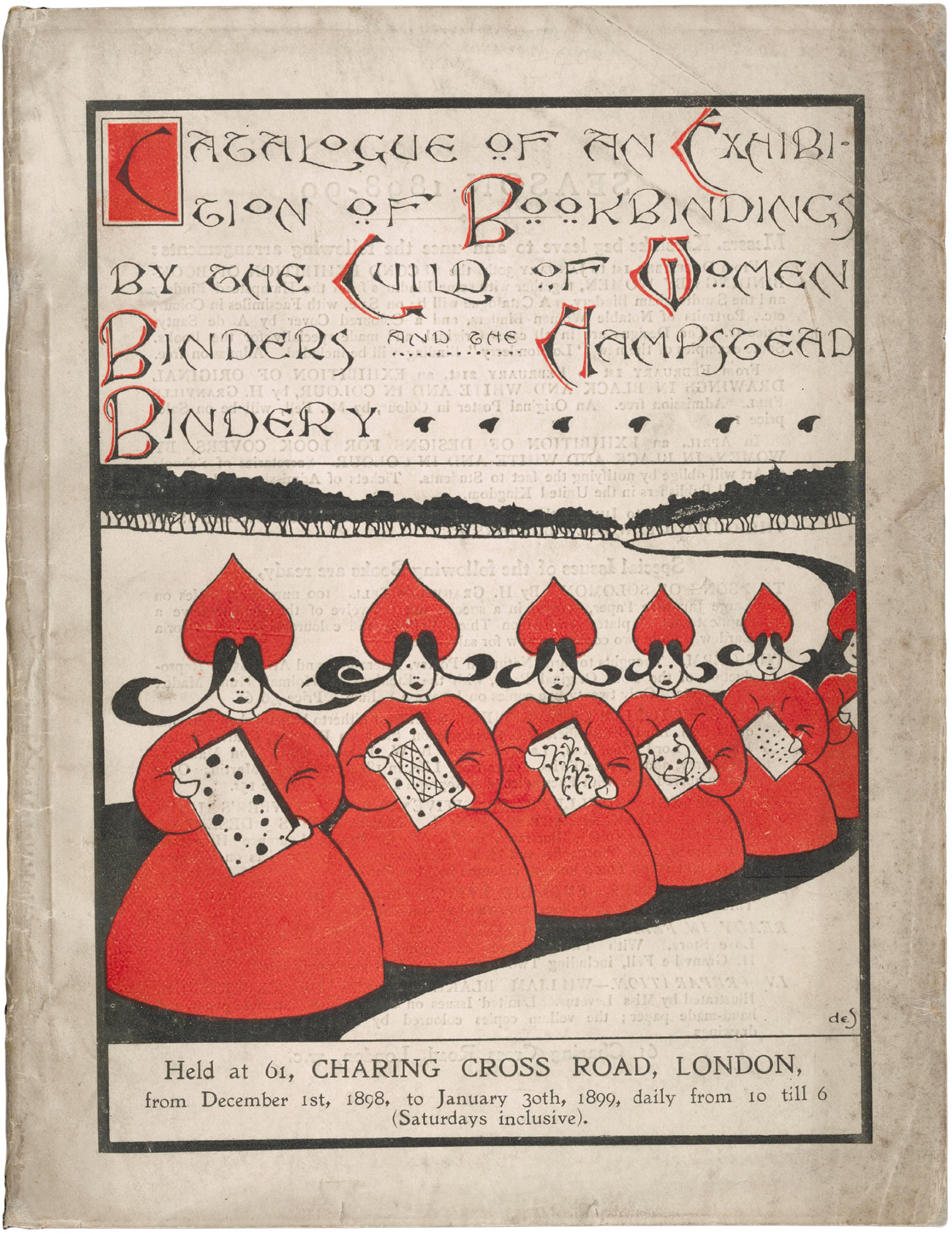

Baskin describes the collection’s focus as “social history,” but she stretches that rubric in unexpected directions. So while she amassed pamphlets and periodicals that exploited the expediency of printing for broadcasting ideas, she also pursued the sumptuous handmade bindings created by women aligned with the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts movement. Baskin understands printing and design—she has worked in the rare book trade, and her late husband was the artist Leonard Baskin, whose Gehenna Press provided a bracing New England riposte to the languid grace of the French livre d’artiste. She recognizes that choices of materials and modes of facture can also be statements of social ideals: in the case of Emma Goldman’s anarchist monthly Mother Earth, production decisions were driven by the need to spread the word broadly and inexpensively; in that of Phoebe Anna Tarquair’s illuminated manuscript of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, they mark a stand against the dehumanizing effects of industrialization.

The progressive politics underlying both Goldman and Tarquair’s ambitions have been a driving force in Baskin’s life, and have shaped her collection in ways both explicit and implicit. Coming of age during the civil rights movement, Baskin cut her political teeth participating in anti–Vietnam War protests. When feminism burbled up as a political principle and cultural critique, she was there. By the late 1960s, she was, she writes, actively collecting “things relating to women.”

The sloppy inclusiveness of “things” is apposite: in and around the incunabula and swish artisanal bindings is a wealth of ephemera and “realia,” the librarian’s umbrella term for all manner of objects that add context or evidence to an archive. These range in scale and importance from Virginia Woolf’s writing desk to mass-market tchotchkes. As Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger notes in the catalog, many of the collection’s holdings “are humble in and of themselves, not especially rare, and this is one of the best things about it.” Baskin’s attraction to dead people’s business cards, for example, is peculiar only until you begin reading, and encounter people like the wonderfully named Eleanor Ogle. She was a fruiterer in Covent Garden, but any whiff of Eliza Doolittle seediness is snuffed out by the rococo profusion of pineapples, melons, overflowing baskets, and sinuous copperplate of her engraved card.

The collection’s cache of household goods reflects bourgeois domesticity while also often advertising political beliefs, not always in straightforward ways. The suffragette swag includes a tea service designed by Sylvia Pankhurst for the Women’s Social and Political Union, in addition to buttons and banners, sashes and scarves. A posthumous ceramic statuette of the gender-bending Ladies of Llangollen in Wales (Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who lived together for fifty years) portrays them in their twin top hats and black riding habits, rosy cheeked and adorable. Manufactured for nineteenth-century middle-class mantelpieces, it signals an unlooked-for willingness among Victorian householders to accommodate “queer” as a subset of “quaint.” (Meanwhile, a letter and engraved portrait of the Chevalière d’Eon serve to document the still less expected accomodation of authority to gender ambiguity: an eighteenth-century French soldier, diplomat, and spy, d’Eon officially lived forty-nine years as a man and thirty-three as a woman.)

Baskin’s collection has extensive holdings on race in America, including important works by African-American women such as Harriet Wilson’s 1859 novel Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, Ida B. Wells’s 1893 pamphlet denouncing the exclusion of “colored Americans” from the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, and Lizelia Augusta Jenkins Moorer’s 1907 book of poems about rape, lynching, and peonage under Jim Crow. Their words, like those of Wheatley and Truth, articulate a breadth of experiences and understandings rarely represented in American literature. The abolitionist paraphernalia on view necessarily condensed such complexities to moralizing messages designed to bring the point home, sometimes literally. What are we to make of the dessert plate printed with antislavery verses and an image of an African mother and child? Can we imagine its abolitionist owners tucking into a blancmange while reading “So Christian Light dispels the gloom/That shades poor Negro’s hapless doom”? Or did the plate sit sequestered in the china cupboard, virtue-signaling across the dining room?

Advertisement

“Five Hundred Years” marks no division between political, economic, and domestic life, since for women there rarely was one. Women’s work was almost never separable from family. Obligation and opportunity (such as it was) went hand in hand. This can be seen in the biographies of women in the printing and book trades: Jolande Bonhomme, who produced the fine Book of Hours (1546) in the exhibition, was the daughter and wife of printers. In colonial Annapolis, Anne Catherine Green inherited a printshop from her husband, and later went into partnership with her son; included at the Grolier was an $8 note she produced for the colony of Maryland using an esoteric anticounterfeiting process that cast relief-printing blocks from found leaves (the specific, inimitable irregularity of the leaves would have been almost impossible to replicate by hand-cutting).

Geronima Parasole, who created spare, robust woodcuts for Antonio Agustín’s 1592 study of antiquities, belonged to a Roman family of printmakers and painters; her sister-in-law Isabella (Elisabetta) Catanea Parasole made exquisite lace-pattern woodcuts (shown four years ago in the Metropolitan Museum’s “Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620”). One of the show’s most entrancing artworks was Anna Maria Vaiani’s engraving for Flora, overo, Cultura di fiori (1638), in which the stalk of an umbellate narcissus rises, solid as a lamppost, then breaks out in a burst of muscular blooms. The daughter of a Florentine painter and engraver, Vaiani was in correspondence with Galileo, and is herself the subject of a magical, small engraving by Claude Mellan. In the right circumstances, families enabled women to be active participants in the artistic and intellectual life of their time.

By the nineteenth century, however, such family operations were giving way to academies and other professionalized modes of training that sidelined women. The Arts and Crafts movement presents a particularly poignant example of this shift: egalitarian, even socialist, in orientation, it sought to repair the alienation of labor in industrialized societies by championing traditional forms of hand facture, many of them long practiced by women. In order to elevate the social and intellectual standing of these activities, organizations and schools were founded—many of which refused women (or as Charles Ashbee, founder of the Guild and School of Handicraft in London, put it, “the lady amateur”), such that the women bookbinders in Baskin’s collection had to seek out separate venues to perfect their skills and exhibit their work.2 Making things for the home could be seen as a kind of potentially charming, undervalued neighborhood of endeavor ripe for gentrification (gentification?) by men.

Undoubtedly, the greatest factor governing women’s lives until recently was pregnancy, and Baskin’s collection is rich with attempts to manage it. Centuries of books on midwifery are complemented by Margaret Sanger’s 1914 pamphlet Family Limitation, an antique contraceptive sponge in a kind of knitted snood, and a delicately worded trade card from around 1785 through which Mrs. Phillips offers “machines, commonly called implements of safety” or, more commonly still, condoms. A lurid biography from the end of the nineteenth century promises to tell all about “the most terrible being ever born,” Madame Restell, who became wealthy providing abortions in New York and who, after being charged under the Comstock laws in 1878, slit her throat before facing trial. And there is the weirdly fascinating pocket obstetrics model book (Geburtshilfliches Taschenphantom) featuring an interactive arrangement of pelvis, baby head, and forceps—at once anatomically accurate and trippily Dadaist in its bio-mechanomorphism (think early Picabia sharing space with Hannah Höch).

For most women, the facts of childbearing could not be separated from the realities of child-rearing. Apart from nuns, precious few women would have led lives in which the supervision of children was not an incessant reality. Martha Maxwell had a daughter and six stepchildren. Anne Catherine Green ran her business while raising six children and burying another eight. Maria Gaetana Agnesi never married but was responsible for teaching her twenty full and half siblings.

Suffice it to say, undivided focus is a luxury that women rarely enjoyed. This is a fact, but is it always a liability? In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf argued that the eruption of female genius in early-nineteenth-century novel-writing was the result of middle-class households having only one sitting room, since the endless social interruptions that kept women from pursuits such as writing history also provided them with the material and insights for writing fiction. A corollary may be seen in the same era’s proliferation of women writers of popular science. All that hand-holding and learning to pitch one’s language at the level of receiving ears could be put to professional use in making intimidating ideas approachable. The frontispiece of Margaret Bryan’s 1799 Compendious System of Astronomy shows the (very comely) English author accompanied by her telescope, armillary sphere, sextant, globe, and two young daughters, as if to say, “Nothing to fear here!” (There was a neat counterpart to this at the Grolier in the form of a French schoolgirl’s captivating, hand-drawn report on Ptolemaic and Copernican astronomical models.)

The Irishwoman Mary Ward (mother of eight) wrote and illustrated Telescope Teachings (1859) as well as volumes on microscopy and entomology by making “time for her scholarly work after her children were in bed,” the catalog notes. The artist and scientist Orra White Hitchcock of Amherst (mother of six) produced more than a thousand illustrations for books by her husband, geologist Edward Hitchcock, and a large body of charts and posters for use in classrooms.3 The 1893 edition of The Fairy-land of Science is an eye-catcher, its cover crowded with gold fairies hugging seashells, climbing morning glories, and pouring luminous goo over the book’s title. This tweeness is misleading: the book’s author, Arabella Buckley, had been secretary to the great geologist Charles Lyell, and the journal Nature said of Fairy-land, “We do not know of a more interesting nor useful gateway to science.”4

In the political sphere, we might consider Harriet Beecher Stowe (represented here by a blurb she wrote for Sojourner Truth), who ascribed the emotional power of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to the loss of one of her own seven children. The book’s unprecedented popularity transformed what had been an abstract political and economical debate into a visceral, “family values” issue, and substantively shifted American public opinion.

Rachel Carson was born too late to feature in “Five Hundred Years,” which closes on the early-twentieth-century strains of women’s suffrage and Arts and Crafts, but it is possible to see Silent Spring as a convergence of these scientific and political streams of affective female popular writing. Though unlike her nineteenth-century antecedents Carson had the benefit of a university education, she too was forced to frame a career by maneuvering in and around familial responsibilities.

When working on A Room of One’s Own in 1928, Woolf went to the British Museum Reading Room in search of Elizabethan women writers. She came up empty-handed, and devoted a chunk of her essay to explaining why the existence of such writers would have been impossible. A half-century later, however, Baskin was setting Anne Bradstreet’s poems and Elizabeth Jane Weston’s compendium of poetry and other writings, Parthenicon Libri (circa 1606), on her bookshelves. The problem was not that such writers had never existed; it was that sometime between 1700 and 1928 knowledge of them had slipped through the cracks (perhaps tipped by the helpful toe of a male brogue).

The allure of seventeenth-century poets of any gender is unclear to many modern readers, but a similar fug obscured works that should have been more broadly appealing. When Baskin acquired Maria Sibylla Merian’s De europische insecten (1730) around 1966, Merian was hardly known outside antiquarian circles. Today, she is as close to a household name as is possible for a seventeenth-century bug specialist to be. This is in part because she presents an attractive model for teachers, museums, and parents on the lookout for examples of historical female scientists, but mainly because her etched illustrations are so spectacularly beautiful. Found today in coffee-table books and ready-to-frame prints, on notecards, shower curtains, and needlepoint kits, they occupy the place in upper-middle-class décor once held by the botanical illustrations of Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Were people just making do with Redouté while waiting for Merian to be rediscovered? Or has something shifted in the culture that makes Merian more relevant? A bit of both, I suspect. Both Redouté and Merian aimed to convey visual information that would help readers identify species, but while Redouté’s perfect blooms hover in isolation, Merian’s plants are part of a natural order of eater and eatee. The “Five Hundred Years” catalog reproduces a page from her book on metamorphosis, in which moth, pupa, and caterpillar converge on a thoroughly gnawed black cherry sprig. Where Redouté provides building blocks for an ancien régime garden, Merian gives us ecosystems.

One of the stories told in “Five Hundred Years” is that of the recovery of works, like Merian’s, that have become integral to the way we now think. It is thanks largely to the women of Baskin’s generation who bent themselves to the tasks of scouring archives and flea markets, and of educating younger scholars to the same, that a present-day seeker of Elizabethan women poets can simply go to Wikipedia’s “List of early-modern women poets (UK)” and be redirected to biographies of Bradstreet and Weston and another 130 published authors, and that pictures of three-hundred-year-old caterpillars chewing cherry leaves grace hotel hallways.

The generously illustrated catalog for “Five Hundred Years” benefits from and contributes to this bounty. In a nod to the collection’s purpose, the book was written and produced by women, down to the design of the typefaces. It is not a weighty scholarly endeavor in itself but, pointedly, an invitation to scholarship. It includes Baskin’s account of how the collection took shape, and essays by Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger and Laura Micham survey the acres of potential dissertation topics the collection holdings might nurture. The short writeups of individual items function as teasers to send readers off Web spelunking. Similarly, the world of digital resources can act as a welcome adjunct to exhibitions such as this: a visitor beguiled by Martha Maxwell, for example, can go home, boot up the Internet Archive or Hathi-Trust, and read On the Plains cover to cover.

That said, Baskin’s “things relating to women” are, importantly, things. Their physicality carries content that evaporates in digital summary. The heft and elegance of Eleanor Ogle’s trade card made me stop and look, but I would have slid past it on Instagram. The adjacency of objectively “important” works, like those by Merian, made me think.

In a biography of the nineteenth-century artist and feminist Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, Pam Hirsch noted that Bodichon “did many things, and historians seem to find it easier to understand and write about a man who pursued one ‘great’ goal. Women’s lives and women’s histories often look different, more diffuse, and are (perhaps) harder to evaluate.”5

This issue of evaluation has been a perennial problem for those seeking to revise the historical canon. At what point does such revision become special pleading? In her influential 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” Linda Nochlin threw gauntlets at the feet, not only of the art historical establishment, but also of overenthusiastic boosters of female achievement: “The fact, dear sisters, is that there are no women equivalents for Michelangelo or Rembrandt, Delacroix or Cézanne, Picasso or Matisse.”6 Her point was that the degree to which talent is brought to fruition is a reflection of the cultural contexts, opportunities, and social structures that enable or disable it.

The exhibition at the Grolier, to some degree, illustrated her point. If the yardstick is lasting cultural impact, an unsympathetic observer could object that, however remarkable Katharina Schütz Zell was as a Reformation pamphleteer, she was not Martin Luther. Laura Terracina was not Shakespeare, and Maria Gaetana Agnesi was not Euler. In the category of scientific works published in 1859, Mary Ward’s Telescope Teachings is not On the Origin of Species.

The one domain in which cultural history is undeniably chockablock with female A-listers—the anglophone novel—was, tellingly, underrepresented at the Grolier. There was an early edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but nothing by Jane Austen, George Eliot, or Edith Wharton. Charlotte Brontë was present, not through copies of Villette or Jane Eyre, but through a letter in which she mentions seeking work as a governess, and through a stitched sampler. This last—made by the hand that penned Jane’s complaint against a stultifying life of “playing on the piano and embroidering bags”—is neither masterful nor beautiful. It is, however, redolent of what regular life in Haworth Parsonage must have been, even for a genius. The sampler matters, not because it is a great work of art, but because it makes tangible something that Jane Eyre can only state.

Emma and Jane Eyre don’t need to be here; their slots in the canon are secure. But their absence, I suspect, reflects a broader understanding on Baskin’s part that, for the insights she meant her collection to spark, the very concept of “A-listers” is silly.

Ninety-odd years ago Woolf posed a rhetorical question: “Is the charwoman who has brought up eight children of less value to the world than the barrister who has made a hundred thousand pounds?” She then observed, “It is useless to ask such questions; for nobody can answer them. Not only do the comparative values of charwomen and lawyers rise and fall decade to decade, but we have no rods with which to measure them even as they are at the moment.”7

We are still missing these rods, but in the ecumenical embrace of “work” rather than the subjective, hierarchical “achievement,” Baskin suggests where we might start looking.

This Issue

March 26, 2020

The Party Cannot Hold

Escaping Blackness

Left Behind

-

1

Mary Dartt, On the Plains, and Among the Peaks; or, How Mrs. Maxwell Made Her Natural History Collection (Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1879), p. 5. ↩

-

2

Charles Ashbee, Craftsmanship in Competitive Industry (Campden: Essex House Press, 1908), p. 37. ↩

-

3

An exhibition devoted to these drawings, “Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock,” was organized by the American Folk Art Museum in 2018. ↩

-

4

“Our Book Shelf,” Nature, Vol. 19, No. 265 (January 23, 1879). ↩

-

5

Pam Hirsch, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon: Feminist, Artist and Rebel (London: Chatto and Windus, 1998), p. ix. ↩

-

6

Nochlin’s essay was published in two slightly different versions in 1971: the January issue of ArtNews under the title “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” and in slightly different form as “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?” in Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness, edited by Vivian Gornick and Barbara K. Moran (Basic Books, 1971). ↩

-

7

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (Mariner, 1989), p. 40. ↩