Glenn O’Brien was the leading boulevardier of my particular subgenerational pocket, the one that thrived in lower Manhattan from the last days of the hippie era until sometime around the end of the 1990s. He was an exemplary if atypical citizen of its culture, and something of a figurehead as it evolved from local, fringe, and “underground” to international high fashion. He lived and worked on the leading edge of style at all times, and was invariably at the right club at the right hour on the right night, but his résumé suggests someone from an earlier era. As if he had flourished during the Regency or the fin de siècle, he was a dandy and a wit, an aphorist and a tastemaker. Although his point of entry was Andy Warhol’s Factory (he was born in Cleveland, attended Georgetown, and was a graduate student in film at Columbia before getting there), he worked primarily with words, as magazine editor, book editor, columnist, and publicist. He exuded cool, sangfroid, and—unusually for the time and place—quiet competence.

But those jobs, for all the money, prestige, and mobility they gave him, were not his primary claims to fame. In that era careerism was regarded with suspicion, and in that much more physical time he made his mark by his sheer presence on the scene: his role as both a throwback (some part of him always inhabited the world of The Sweet Smell of Success) and as the very image of hipness. His cultural footprint was broad and significant, if not always noticeable to the average cultural consumer. He was putatively most visible as the underwear model on the Warhol-designed inner sleeve of the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers (1971)—although the jury is still out on whether his picture was the one actually used.

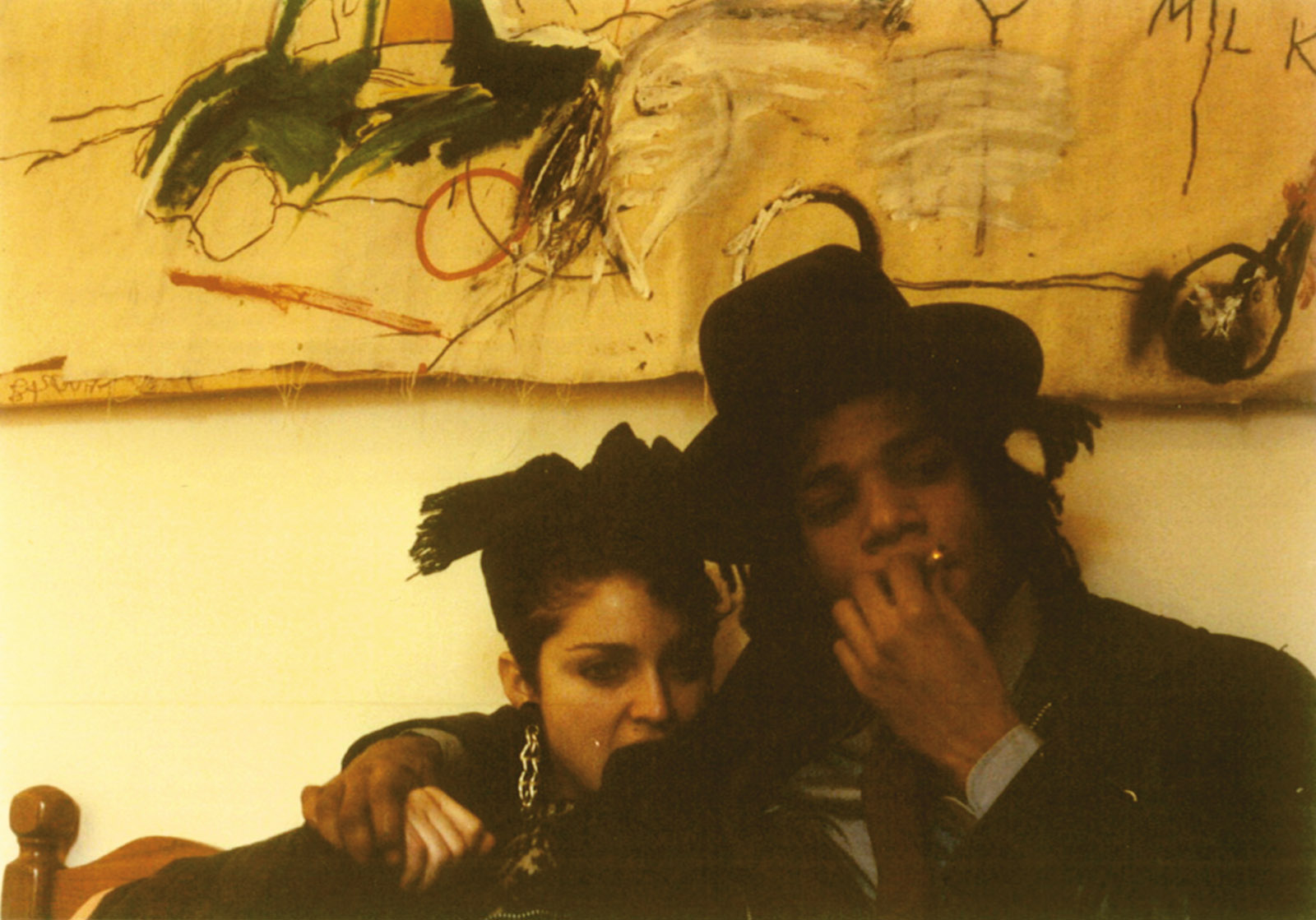

O’Brien, who died in 2017, was the host from 1978 to 1982 of TV Party, an antic talk/variety show with an audience that was restricted to people, largely in lower Manhattan, who could tune in to the public-access cable channel on which it ran (a set of DVDs has since been issued). In 1981 he wrote and produced a feature film starring Jean-Michel Basquiat, a youthsploitation picaresque originally titled New York Beat, but financial woes kept it from being released until 2000, when it was retitled Downtown 81 and took on an entirely different significance—historical and elegiac, in view of Basquiat’s early death.

And he edited Interview (1971–1974); worked at magazines ranging from Rolling Stone to High Times to Allure, Spin, Maxim, Mirabella, Purple, and Arena Homme Plus; cowrote and edited Madonna’s Sex; edited some other touchstones of the period (Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School, Terence Sellers’s The Correct Sadist); wrote a column on advertising for Artforum (“Like Art,” 1984–1990) and one on men’s fashion for GQ (“The Style Guy,” 1999–2015); and briefly toured a conceptual standup comedy act in which he covered, as a musician would a song, a routine by the legendary B.S. Pully, who played Big Jule in Guys and Dolls and was known for working blue.

He was also involved in the advertising business himself, starting as a copywriter for the late Barneys New York chain in 1986 and becoming its creative director two years later. After that, he worked for Calvin Klein. “I did the ‘Marky Mark’ underwear campaign with Kate Moss, and the jeans campaign that President Clinton demanded be investigated by the Justice Department,” he wrote in “The Story of My (Work) Life [Long, Stalker Version],” a bio on his website. (In that 1995 campaign, young models, male and female, are interrogated by an offscreen voice. Nothing untoward occurs, but the innuendo is laid on thick, from the cheap carpeting and fake-wood paneling of the set to the light leaks and bits of leader in the film to the questioner’s voice and affect—fiftyish, gruff, insinuating. Everything suggests a screen test for porn, at best, and probably something worse.) He represented perfume, hotel chains, bottled water, and U2, and “named and positioned the interiors company…Royal Hut.”

If this was problematic for some, no one mentioned it. After all, in the 1980s art and commerce became fully acknowledged bedfellows. Artists were photographed wearing banker suits and smoking Montecristos, strove to be featured in ads for Absolut Vodka, caroused with real estate magnates and deep-pocketed promoters with unplaceable accents. Once-ragged lofts were given makeovers; the potato fields of the Hamptons were plowed under for new constructions of ever-increasing size; VIP rooms made it possible to go clubbing without risk of contamination by the unwashed; and anybody who was anybody ate in the kitchen at Mr. Chow’s, because it only held one table—reservations not accepted. It was all as Warhol had foretold, with additional glitter from the wand of supply-side economics.

Advertisement

O’Brien was quite sanguine about all this. “Advertising was like art, and more and more art was like advertising,” he wrote near the end of his life. “Ideally, the only difference would be the logo. Advertising could take up the former causes of art—philosophy, beauty, mystery, empire.” He felt that Barbara Kruger’s work, in which she employed advertising techniques to highlight social and cultural contradictions, was merely inferior advertising: “There are no ethics in fashion. There are no ethics in magazines. There are no ethics in advertising.” Naturally, he was a liberal; he despised Trump, the NRA, Israeli apartheid, the sanctioning of Cuba—he also despised burqas, on which he took the French government’s view.

He was, more precisely, a Kennedy White House liberal, who believed in honor, truth, justice, a few laughs, and a good pour. The Chinese silk banners of Marx and Engels that hung on the TV Party set were merely a pun on the word “party,” although he had at least sampled Marx. He just thought it was time for Marx to chill. He was an achiever, a print-world architect with a wide range of social and practical skills, who charmingly pretended to be a gentleman of leisure but would never go hungry in his lifetime. He was educated by the Jesuits, which means that he wore Irony in scarlet on his breastplate.

No wonder he cut such an odd—and oddly beguiling—figure in the New York low bohemia of his youth. It must have been a great day at the Factory when he first walked in, sometime in 1970: here was a potential future member of the ruling class, somehow handsome and intelligent at the same time, who had internalized the principles of cool so deeply that he always pitched his voice as if he were selling you reefer in the men’s room at Minton’s in 1946. And he was keen on hanging out with people who were not like him, which was pretty much everybody at the Factory. (He was, for one thing, heterosexual.) Despite circumstantial differences, he instinctively grasped and absorbed Warhol’s view of the world. He understood the transience of fame, the power of the image, the somatic effect of repetition, the allure of emphatic understatement, and the contrapuntal sympathy between the ordinary and the transgressive. Some other people did, too, but like Warhol and unlike most of them O’Brien possessed an innate executive ability that would allow him to make hay from those insights.

Intelligence for Dummies is subtitled “A Portrait” on its cover, which suggests that it is not so much a Selected or a Best-of as an attempt at an ideal representation of someone whose virtues did not all lie on the page. It is magazine-like in its layout, with different fonts and sizes of type, sliding margins, occasional bursts of double columns, and many artful photographs unobtrusively illustrating the pieces. It mixes together essays, columns, and tweets under six broad categories (“Being Glenn O’Brien,” “Art,” “Politics,” “Music,” “Advertising,” and “Fame, Fashion and Living”). These make for a complex, multifaceted presentation that exemplifies O’Brien’s many contradictions. He was a gifted writer, although his most formally realized works largely appeared in art monographs and exhibition catalogs, which were, as always, read by few.

His major impact as a scribe came from his columns, which were many, some of long duration. In that function he shone. He was a brilliant maker of remarks, and his remarks on the page are of a piece with his remarks in the field. The trouble with remarks is that they seldom survive their context, meaning their time. When he wrote his column “Glenn O’Brien’s Beat” for Interview in the 1970s and 1980s, for example, each installment was like a phone call from its author, relating news, gossip, gags, passing observations, and sharp judgments delivered offhand. It possessed urgency and resonance. But phone calls dissolve into the ether along with the strings of information that bind them to the world. And no one writes a column sub specie aeternitatis. You can footnote all the proper nouns, but not the wind blowing through the streets at the time of writing.

Think of columns as much longer tweets; the years will turn their gossip, trends, forecasts, and recaps to mud. It’s impossible to quote one of that era without accidentally including a Dan Quayle joke. Fortunately, O’Brien had several other modes. He was at his best with the subjects that engaged him most directly, such as fashion advertising:

Why don’t [many] publications allow criticism of fashion? Because fashion brings home the proverbial bacon, Osbert. That’s why we are so blasé that it’s nothing getting the New Yorker with a two page Versace ad that features two five figure hookers on a bed on drugs, one passed out in a garter belt showing her complete ass and the other making goofball eye contact with the reader, as it were, and this is a normal thing, because fashion brings home the bacon.

(He did keep his eye on the bottom line: “Andy [Warhol] must have realized then that even if film was his future, painting was still the way to bring home the bacon.”) And he could imaginatively project himself into a consciousness that feels like kin, as when he looked at photographs of Kurt Cobain after his death:

Advertisement

He is slumped as if exhausted or about to fall down—but junkies don’t fall down—maybe it’s just “I have very bad posture.” Kurt is knocking back a quart of Evian, unlike Keith and his Jack Daniels. He is lucid, but still the light seems to be flickering. The pose is obvious. His posture is crushed. He’s in a slump. He’s on the edge of the world we inhabit, peeking into another.

But then he could be cornball or vaguely fogeyish, as in his complaint about the decline of embarrassment or his proposal for a Guilty Party in the elections or his suggestion that the Pentagon sell ad space on the B-2 bomber. As befits a dandy, he excelled at handing out advice:

It’s always better to be overdressed than underdressed for an occasion. It will appear that you are going somewhere better later.

If you order white wine in a restaurant and it’s not cold enough, dump the contents of a salt shaker into the ice bucket and mix well.

So some of these pieces now fall flat, sound like routines or, worse, like historical ephemera. Some of the contents here remind me of the volumes of midcentury modern saloon chatter by Bennett Cerf, which as a kid I found enjoyably mystifying when I’d turn them up at yard sales. Not coincidentally, O’Brien acknowledges his debts to Steve Allen and Jack Paar, urbane talk-show hosts of that same era, and his choice of profession is unavoidably connected to the period as well: “The creative executives enjoyed much of La Vie de Bohème, hobnobbing with photographers and models, frequenting jazz clubs, possibly smoking an occasional jazz cigarette.”

What chiefly distinguished O’Brien from his downtown milieu was that at no point was he ever a bohemian. Instead, he was, eternally, a hepcat: “Hip is a noun, a verb and an adjective. Hiply is the adverb. Hip is a joint. When hips get together they do the bump. They do the hip shake. When a hip gets cut off and smoked, it’s a ham.” He was hip beginning at the very last point when hipness was still connected to secret knowledge imparted by members of a disenfranchised minority, in his case largely by gay men. He remembers the era in lower Manhattan when common aesthetics and partying proclivities seemed to override other sorts of identity:

Everywhere Andy went we all went. Usually we would wind up dancing at a club. The clubs we went to were basically gay discos but they were integrated in a way that no longer exists as far as I know. We were a weird posse of gay and straight guys and straight girls with wandering tendencies.

The book is something of a curate’s egg, but then he wrote so damn much, much of it tossed-off and time-sensitive, and the specific lines I can recall are mostly wisecracks, although his wisecracks are pretty good. He places a signature line in Basquiat’s dialogue in Downtown 81 (ventriloquized by the singer Saul Williams, since the original soundtrack was lost), referring to the art-world magus Henry Geldzahler as “Henry Godzilla.” The real keepers in this volume are precisely detailed and often moving evocations of his friends: Warhol, Basquiat, Nan Goldin, Richard Prince, James Nares. He conveys them in ways that are strangely difficult to quote, since they are contingent on chatter, circumstance, anecdote, and location, and evoke by accretion:

I remember Jean-Michel saying Boom all the time. It was an exclamation point with right on built in. Boom. Boom. Boom for real.

I remember the way he talked, soft but really fast and forceful. Urgent you might say. With Jean-Michel everything was urgent.

I remember him painting a painting that was so great and then just painting over it and that was so great.

The book is handsome, although the design can be distracting (I found myself inadvertently avoiding the pieces set in sans-serif type), and there are far too many typos for a professional production, some of them substantive (Lee Perry somehow appears as “Leo Perry”). For people who did not know O’Brien, it can only point in the general direction of his physical presence, which is much more of a consideration than it would normally be for a writer: his deadpan stare, his sotto voce, his timing, his imperturbability, and of course his sartorial magnificence. Readers are advised to look up the listicle published by GQ after his death, which spotlights the jewels of his closet: his double-breasted cream-colored shawl-collared dinner jacket by Steed, of Savile Row; his battered John Lobb ghillies; his hand-painted neckties and Charvet shirts; and the crown jewel, the Perfecto jacket on which Basquiat painted his trademark crown between the shoulder blades, a garment that should guarantee admission to heaven.

This Issue

April 9, 2020

Bigger Brother

Stuck

In the Time of Monsters