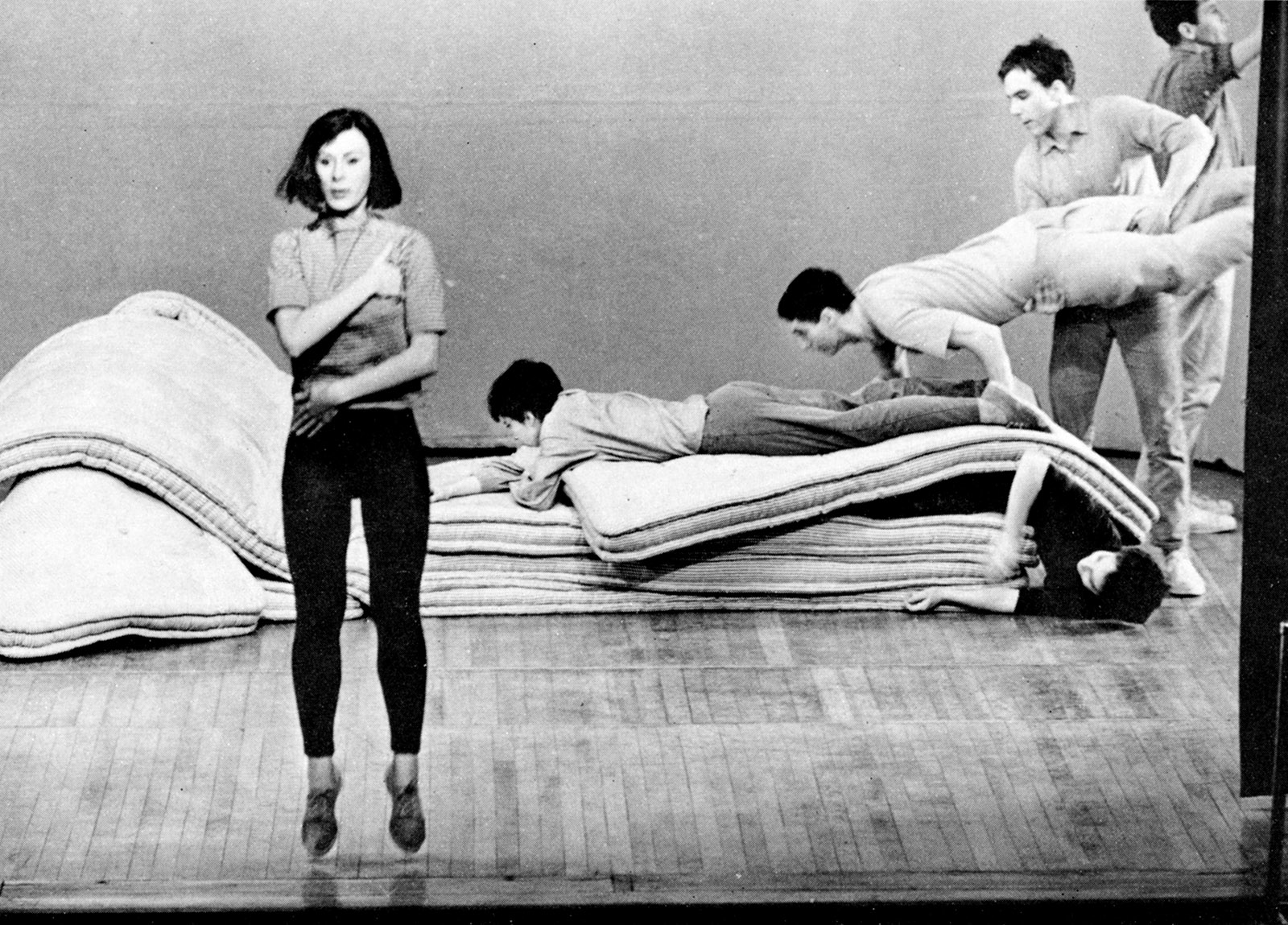

In March 1965 the choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer went to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, to premiere what she described as “a dance for ten people and twelve mattresses.” It was called Parts of Some Sextets. In the performance, she and nine other participants moved at thirty-second intervals through various combinations of thirty-one tasks, from sitting and resting to piling atop the mattresses like “human flies.” For the score, she taped herself reading excerpts from the recently republished diaries of William Bentley, a Salem pastor who recorded thousands of “daily occurrences” between 1784 and his death in 1819. “The dance ‘went nowhere,’ did not develop, progressed as though on a treadmill or like a 10-ton truck stuck on a hill,” Rainer wrote that winter in an essay that reappeared nine years later in Work 1961–73, an extensive anthology of photographs, diagrams, choreographic notations, event programs, and writings about her earlier dances, newly reissued by Primary Information after a long time out of print. “It shifts gears, groans, sweats, farts, but doesn’t move an inch.”

But as the dance went on it developed its own kind of coherence. For last year’s Performa Biennial, Rainer and her longtime collaborator Emily Coates restaged it for the first time in more than fifty years, using the surviving five eighths of the notation (a vast grid reproduced in Work 1961–73 of which the rest seems to have been lost), Peter Moore’s photographs of a 1965 performance, and a newly uncovered recording of Rainer’s original voice-over. They added an eleventh dancer and filled in the piece with new choreography but in other respects stayed close to the original staging. The dancers, as they had in 1965, stacked the heavy mattresses, crawled between them, leapt onto them, held hushed conversations around them. At various points they handled other props, too: a gear, ropes, a plush disc from a red wooden box. Thrumming under that chaotic movement was Rainer’s uninflected recital of anecdotes, rumors, and grim spectacles from Bentley’s Salem: the exhibition of an elephant; a solar eclipse; the public whipping of “some offenders”; the discovery, in a hollow tree, of two barrels of “swallows in a torpid state.”

Over the past sixty years, Rainer has made an art of bringing a deadpan comic tone to scenes of strenuous activity: bodily exertion, illness, political struggle, emotional strain, taxing dialectical thought. Throughout the pieces she choreographed for Judson Dance Theater, the influential collective she cofounded in 1962, the performers might dress in street clothes and run laps around the stage, like the participants in We Shall Run (1963), or caress one another while matter-of-factly acting out “an irregularly timed dialogue” of romantic clichés, as Rainer and William Davis did in the “love duet” from Terrain (1963). In the first version of her best-known piece, Trio A (1966), three dancers cycle through strung-together, unconnected tasks—bending their knees, furling their arms around their waists, tilting their heads, wilting to the ground—that emphasized their indifference to the audience’s gaze. (Rainer told the scholar Carrie Lambert-Beatty in 1999 that it was “a dance in which you really have to lug your weight around.”) In Work 1961–73, Rainer remembered rehearsing Trio A with the dancer and choreographer David Gordon. “I’m thinking of myself as a faun,” he told her. “Try thinking of yourself as a barrel,” she said.

Rainer often says that her work depends on “radical juxtaposition,” a phrase she took from Susan Sontag to capture the disorienting cuts and swerving modes of address that organize her movies and dances. The seven feature films she made between 1971 and 1996 are dense collages of image, text, and sound: photographs, monologues, repurposed fragments from her dances, staged scenes, typewritten intertitles, and tableaux vivants, often overlaid with loquacious voice-over tracks. Most of these movies center on artists and writers stuck in destructive love triangles or burdened by the feeling that, as a fragment of onscreen text says in Kristina Talking Pictures (1975), “they remained uncommitted and untouched” by the crises erupting around them. With each film, Rainer seemed to linger longer over concrete political conditions: the West German state’s “transformation of political opponents into political criminals” in Journeys from Berlin/1971 (1979), for instance, or “the ignominious death of Guatemalan or Salvadoran peasants” at the hands of US-backed death squads in The Man Who Envied Women (1985).

“My films always were meant to confound in a certain way,” Rainer told the video artist Lyn Blumenthal in 1984.1 Several years after she came out as lesbian around 1990, she made a feature, MURDER and murder (1996), about a romance between two middle-aged women. Midway through the movie, the couple fights a slapstick boxing match in a ring decorated with printed statistics about breast cancer. Rainer, meanwhile, sitting on the sidelines, exposes her mastectomy scar and gives a monologue about the five biopses that led to her diagnosis. She was playing “the Rainer character,” she told Lambert-Beatty. Earlier in the film, she says from a TV monitor that her mother accused her of bringing up “ancient history” in an autobiographical early dance. “Sometimes my life feels like one ancient history piled on another,” she says. “It’s enough to curdle the blood.”

Advertisement

Rainer was born in 1934 and raised in the Bay Area. Her mother, Jenny Schwartz, the daughter of Polish-Jewish immigrants, grew up in East New York. She met Rainer’s father, an Italian house painter and contractor named Giuseppe, in a “raw food dining room” in North Beach. They went to picnics hosted by local Italian anarchists and married only after Rainer and her older brother, Ivan, had been born. By the time Rainer was four, her mother had fallen into a deep depression, and her parents were sending her and Ivan to “a series of private foster situations” that culminated in a dismal group home called Sunnyside.

Eventually they came to live back home. In her memoir, Feelings Are Facts (2006), Rainer writes with pain, tenderness, and striking sensory precision about the objects of estrangement that structured her early life: the stove in which she burned her used Kotex pads with a poker; the paste-like deodorant she bought after two girls in art class made sure she knew she smelled; the garage door on which, as a child, she scribbled “Don’t write on here, bad girl.” Dance was one more occasion for bodily discomfort. At Rainer’s childhood classes it was as if all the other students but her could “touch the backs of their heads with their toes.”

She transferred to Berkeley “after a year at San Francisco Junior College” and dropped out after a week. From there, she drifted between cities and jobs, including as an order filler at “an enormous modern warehouse in Evanston” and a ticket seller at the San Francisco Cinema Guild. In 1956 she flew, wearing her “gun-metal Capezio sandals,” from the Bay Area to New York, where she went to matinee screenings of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin movies at MoMA, circulated among Abstract Expressionist painters, and took acting classes.

“I never had a talent for mimesis,” she told David Velasco in a 2012 Artforum interview. But she was still drawn to performance. She was in her early twenties when she signed up for what she called her “first adult dance class,” with a teacher in the West Village named Edith Stephen. She started a grueling daily regimen of ballet classes and contemporary dance courses in 1959, first with Martha Graham and then with Merce Cunningham and James Waring. That year, in a letter to Ivan, she called dance “salvation through sweat.” (She could afford to dance full-time, she remembered in Feelings Are Facts, because for two years starting in 1959 her mother sent her “$10,000 in monthly installments.”) In the summer of 1960 she and her new studiomate Simone Forti drove to the Bay Area for a month-long outdoor workshop with the postmodern choreographer Anna Halprin. They learned improvisation techniques, worked with everyday objects, and collaborated with the experimental composers La Monte Young and Terry Riley. When Rainer sprained her ankle there, she recalled, she joined an improvisation session by doing “something with vocal sounds” and plucking objects out of her bag, “including a tampon in its paper wrapping.” She wrote that the late dancer and choreographer Trisha Brown, who was also at the workshop, later said she had been “shocked at the exposure of this unspeakable object.”

Back in New York, Rainer, Forti, the dancer and choreographer Steve Paxton, and, later, Brown enrolled in a composition class with Robert Dunn, a disciple of John Cage, who taught them to build dances using chance-based procedures like tossing dice and pulling numbers out of a telephone book. The dances they developed during these months put ostensibly everyday activities in startling new arrangements: as Sally Banes wrote in her comprehensive Judson history, Democracy’s Body (1993), Paxton’s Proxy (1961) “involved a great deal of walking; standing in a basin full of ball bearings; getting into poses taken from photographs; drinking a glass of water; and eating a pear.”

Members of this workshop, including Rainer, organized the first Concert of Dance at the West Village’s Judson Memorial Church in 1962. Near the end of the three-and-a-half-hour program, according to Banes, Rainer did a fragmented series of movements—squatting, falling, stomping her feet, bending her torso midwalk—while dryly reciting a monologue about the streets she’d lived on from her childhood in San Francisco to her first apartment in New York. “If you had said this girl is going to walk around and do this thing and talk,” the dancer and choreographer Lucinda Childs told Banes, “I would think you were kidding, or crazy. And instead, it was completely spellbinding.” Rainer called it Ordinary Dance.

Advertisement

The Judson Dance Theater put on fifteen more numbered concerts over the next two years. Each week the group held open meetings—there were no entry requirements—to workshop new dances. In theory, what Judson promised was a radical extension both of who could be a choreographer and what could count as dance: the first of the critic Jill Johnston’s numerous Village Voice columns about Judson was titled “Democracy.”2 There were nonetheless limits to this vision. It “was an overwhelmingly white affair,” as the scholar and performer Malik Gaines wrote in his essay for the catalog of a 2018 Judson exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and one that tended to take its whiteness for granted: Lambert-Beatty has noted that “the period’s focus on the body as a neutral, phenomenological entity rather than a socially defined one” involved a willingness to let race “go unremarked.”3

In a perceptive essay on the occasion of that MoMA exhibit, the scholar Catherine Damman lingered over the glories of Judson’s dances but also stressed that the group’s “celebration of ‘ordinary’ movement” depended on a set of assumptions about what sorts of behavior and ability counted as ordinary.4 How could this supposedly democratizing movement philosophy accommodate people for whom running, walking, or climbing stairs were “exhausting or impossible”? Most of Rainer’s 1960s pieces, if anything, foregrounded how strenuous those movements could be. Her recent ones still do: in Assisted Living: Do You Have Any Money? (2013), the dancer Keith Sabado has to execute ballet steps while reciting a text about Keynesian economics.

And yet Rainer has also been drawn to movements that accommodate injury and illness or give exhausted bodies a chance to rest.5 During the “sleep solo” from Terrain, two performers stood by with “cool detachment” while a third sat on the stage saying things like “buzz, buzz, buzz” and pulling objects—“a small sandstone turtle, a toy gun, two woolen hats, several dried mango pits”—from a carpet bag. In 1964 Rainer wrote that she wanted “to make a dance about sleeping.” It would list the beds she’d slept in and register how strange her body felt whenever she woke up at night in an unfamiliar room. A year later, her friend Robert Rauschenberg—one of the two visual artists, along with Rainer’s then partner Robert Morris, who appeared in the original Parts of Some Sextets—called one of his mixed-media collages Sleep for Yvonne Rainer.

She was in bed when she made her first film: near the end of 1966, the day after she premiered a large-scale production called Carriage Discreteness, she came down with a life-threatening gastrointestinal condition and made a short called Hand Movie from her sickbed by bending, spreading, and folding her fingers in front of a friend’s Super-8 camera. Less than a month after leaving the hospital, she gave a vulnerable solo rendition of Trio A at an antiwar festival called Angry Arts Week under the title Convalescent Dance.

In 1969 Rainer started workshopping a series of performances built from movement fragments she called “chunks and insertables,” including a synchronized group dance with pillows and folding chairs, set to Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep Mountain High,” that became one of her signature pieces. The goal was to simulate a rehearsal: the fragments weren’t put in order until the performance itself. A group of dancers including Paxton, Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, and Becky Arnold performed the “definitive version” at the Whitney Museum in the spring of 1970 under the title Continuous Project—Altered Daily. This collective, which soon took the name Grand Union, kept staging versions of the project until, in Rainer’s words, the group “became wholly autonomous and the work almost totally improvisational.”

That same spring, “roused by the killings on US campuses and the invasion of Cambodia,” Rainer enlisted forty performers to wear black armbands and do a solemn march down Greene Street called M-Walk. In the program notes for her 1968 evening-length performance The Mind Is a Muscle, she had insisted that “the tenor of current political and social conditions” had no bearing on her work. Now, they had become its explicit subject. Later in 1970, she had thirty-one performers dart around a gymnasium for a piece called WAR. Words like “invade,” “confront,” “overthrow,” “search,” “destroy,” and “withdraw” punctuate the instructions she gave them. In Moore’s photographs from one of these performances, some of the participants splay out on the floor on their sides, each with one arm extended, like casualties.

What made her into a filmmaker? “In the broad view,” she told Blumenthal, “it was narrative.” She had been making short films since Hand Movie and incorporating them into her multimedia performances. But by 1971 she had also started drawing on narrative devices like individuated characters and melodramatic plot structures. She was starting to drift away from the idea that a performer could become what in 1966 she had called a “neutral ‘doer,’” unencumbered by personality or charisma. No performance was neutral, she suggested during a 1975 interview with the editors of the feminist film journal Camera Obscura: even “doing” a walk was a matter of “investing it with character.”

In Feelings Are Facts, she remarked how invisible a presence “the nuts and bolts of emotional life” had been in the “high US Minimalism” she had once had a part in defining:

While we aspired to the lofty and cerebral plane of a quotidian materiality, our unconscious lives unraveled with an intensity and melodrama that inversely matched their absence in the boxes, beams, jogging, and standing still of our austere sculptural and choreographic creations.

Filmmaking gave her a new set of methods to deal with those threads of emotional life. In 1971 she made a feature, Lives of Performers, a black-and-white portrait of a love triangle shot by the brilliant cinematographer Babette Mangolte. The performers at the center of the film—played by cast members from Rainer’s recent piece Grand Union Dreams—reflect on their ruined love affairs in voice-over as they dance, sleep, break up, and reunite across a sparse loft. An opening title card calls it a “melodrama,” and Rainer generated a strange emotional power from deconstructing that genre, combining dance material with tableaux inspired by production stills from the Louise Brooks film Pandora’s Box (1929) and episodes from her own recent past.

Her second feature, Film About a Woman Who… (1973), emerged from an evening of slides, film, performance, and narration that takes up twenty-five pages of Work 1961–73. In the movie, Rainer splits an unnamed woman’s anger and nostalgia across intertitles, reporting on them in the third person and embalming them in the past tense. A love affair disintegrates in forty-eight numbered steps. (“She hadn’t wanted to be held,” two titles say. “She had wanted to bash his fucking face in.”) An unsettling episode that Rainer later called a “sexual fantasy” plays out in a single, agonizingly slow long shot of a motionless woman getting undressed by a stone-faced man while Rainer and another woman look on. It dissolves into close-ups of Rainer’s expressionless face plastered with newspaper clippings of Angela Davis’s love letters to George Jackson. The scene both seethes with anger over the public display of women’s intimate lives—Rainer told Blumenthal that she wanted to evoke how Davis’s “most private diaries” had been “revealed in court to be used by the prosecution”—and enacts that same display itself. It made Rainer wonder, she said, “whether I myself wasn’t exploiting Angela Davis in simply using this material.”

In an influential essay from 1974, Annette Michelson suggested that Rainer epitomized the emergence in dance and film of “an art of critical discourse, consumingly autoanalytical, at every point explicative of the problems attendant upon the constant revision of the grammar and syntax of that discourse.” It can seem as if Rainer made all her movies from then on with that description in mind. In the mid-1970s, she switched to color and shifted her emphasis from isolated love triangles to the anxious movements of the social world of the downtown artists and writers among whom she lived and worked. In Kristina Talking Pictures and The Man Who Envied Women, she became that world’s tenderly caustic inside chronicler. Her characters and narrators speak in coiled epigrams that sometimes dwell on the gap between their political commitments and the demands of their daily lives—Do you believe in Chairman Mao and refuse to curb your dog?—and sometimes light up with moral clarity.

Journeys from Berlin/1971 gathers ambivalent reflections on suicide, the German Red Army Faction, and the bitter reversals of history from a handful of ghostly, unnamed figures. We hear four of them but only see one, a self-excoriating psychoanalytic patient played by Michelson, whose monologues give the movie its center of gravity. In The Man Who Envied Women, another invisible artist, voiced by Trisha Brown, narrates her separation from her husband, a smug, chauvinistic professor we see give a long lecture on Lacan. She introduces herself over a shot of him sitting next to a screen as it shows the eyeball-slicing scene from Un Chien Andalou (1928). “It was a hard week,” she says:

I split up with my husband and moved into my studio. The hot water heater broke and flooded the textile merchant downstairs; I bloodied up my white linen pants; the Senate voted for nerve gas; and my gynecologist went down in Korean Airlines Flight 007. The worst of it was the gynecologist. He was a nice man. He used to put booties on the stirrups and his speculum was always warm.

Juxtaposed with scenes from the professor’s life are clips of footage from a Board of Estimate hearing during which longtime residents of the Lower East Side protested the part artists were playing in pricing them out of their homes. The narrator went to one such meeting, she says, when her landlord tried to evict her. What she heard there horrified her: “Property is profit and not shelter. Property is money and not comfort. Property is speculation and not home.” She had “met the enemy” there, she says. “And it was us.”

By the late 1980s, Rainer suggested, the aesthetic rebellions and refusals that had animated much of her earlier work had lost some purchase and urgency. It was “specific social struggles,” like the demonstrations she participated in with a group called No More Nice Girls to protest the rollback of abortion access, that seemed to offer a new ground for radical art. In Privilege (1990), her essay film about menopause, racism, and medical and legal discrimination, she strained to take stock both of the social conditions that exposed her to suffering and of the ones—her whiteness, her position in the middle class—that made her complicit in the suffering of others. (Late in the movie, a boxy computer screen displays a series of first-person memories and confessions, narrated by a white woman, with the title “WHO SPEAKS? QUOTIDIAN FRAGMENTS: RACE.”) The tone is anxious, unresolved. When the critic Thyrza Nichols Goodeve asked Rainer in 1997 to “attach an emotion to each of your films,” she suggested that Privilege was about “ambivalence.” MURDER and murder, on the other hand, ended with the two heroines making chicken soup and talking about feeding the cat—one of Rainer’s few sustained scenes of relaxed intimacy. She said it was about love.

Her return to choreography came in 1999, first with new arrangements of Trio A at Judson and then with a commission from Mikhail Baryshnikov called After Many a Summer Dies the Swan. That piece was full of quotations from the performances cataloged in Work 1961–73. But the late art historian Douglas Crimp, one of Rainer’s most perceptive critics, emphasized how thoroughly she “retooled” the earlier material, including by setting it against “observations on aging, death-bed statements, political commentary.”6

Soon after that performance premiered, she founded a small, informal group of dancers—they’ve become known as “the Raindears”—and started an ongoing series of pieces that build on material from her early work. The program notes for her latest piece, Again? What Now?, which she made for the Weld Company in Stockholm in 2018 and reworked with her collaborator Pat Catterson for nine young dancers at Barnard during her residency there last fall, suggest that it could be called “YR’s Best Bits.”

Her treatment of those fragments has been affectionate but also critical and irreverent. She adapts them for what she has called “the aging body” (she often works with dancers over forty) and layers them with new soundtracks. In Parts of Some Sextets, 1965/2019, the original taped narration alternates with recent recordings of Rainer reading more passages from Bentley’s diaries—“we are full of reports of war so that scarcely anything else is mentioned”—and spitting out expletives implicitly directed, she has said, at Donald Trump. At a 2010 Judson tribute, a month before her seventy-sixth birthday, she danced another new version of Trio A, Trio A: Geriatric with Talking, under a mordant commentary about the moves she’d grown too frail to make.

Again? What Now? opens with a sequence from Terrain that Rainer calls “the Diagonal game,” in which the dancers shout out numbers and letters, then move diagonally across the stage performing movements that correspond to those instructions, including a tiptoed walk with puffed-out blowfish cheeks. (The audience has to extrapolate the rules as the sequence goes on.) Mid-performance is a rendition of Chair Pillow, the beloved Ike and Tina Turner passage from Continuous Project—Altered Daily. Here, as in all of her recent pieces, Rainer gets raucous movement vocabulary from slapstick comedy—she has cited Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy as inspirations—but also seems drawn to texts and music that have a sense of what Crimp called “emergency.” In both Again? What Now? and the disaster-haunted dance The Concept of Dust, or How do you look when there’s nothing left to move? (2015), the dancers form a dense clot and move as a single mass to an elegiac Gavin Bryars composition called The Sinking of the Titanic. Near the start of both pieces, the lights dim for a recording of Rainer reading a New York Times article about the discovery of “the fossil of an ancient hedgehog” that “could give us a better idea about what is happening today if the earth continues to warm.”

Rainer’s work has in most respects been up for constant revision—few artists shift mediums completely once in their career, let alone twice—but it has never stopped depending on these deadpan voice-overs. When she intercut the original tape of her narration with the new one in Parts of Some Sextets, 1965/2019, what stood out was how little her delivery has changed. It moves slowly and with heavy enunciation, as if she were dictating or reading a telegram. (She had a lisp, she remembered in Work 1961–73, until a speech coach urged her in her early twenties to practice a new way of forming sibilants: “So for the next two weeks I slowed my speech by half—no matter whom I talked to: boss, parents, friends, pets—and spoke with no other ‘s’ but that new ‘s.’ And by the end of two weeks I had it licked.”) It can navigate smoothly through intricate syntax and draw out the simplest phrases with a kind of quizzical bemusement until they sound odd and unfamiliar.

If the narration in Rainer’s work is an internal monologue, whose is it? Who is it for? When it narrates anxious, encumbered situations, the voice often seems to be coming from somewhere else, a place of unruffled assurance and unsparing self-analysis. As we worked on this essay, we found ourselves reading in it, thinking in it, wrapped up in the sonic fabric it throws over most of Rainer’s dances and films. We told ourselves it sounded as if it knew where it was going.

In 1964 Rainer taped herself reading an essay she had written about the pleasures and regrets of improvised dancing. “The improvisational situation can produce a helluva lot of anxiety,” she said:

The anxiety also comes when I don’t want to be there—here—right now…. The funny thing is that if I knew—right now—that I don’t want to be here—right now—then I could play with that and possibly turn it into being here right now. But unfortunately, knowing that you don’t want to be here right now usually comes too late to do anyone any good, until maybe next time.

But “next time” was already here. She played the tape during an improvised solo performance. There she was, dancing, “here—right now,” and there the voice was, elsewhere, reflecting on what it was like to be onstage. “Next time I am going to try something new,” the voice said as she continued dancing. “I am going to say ‘It has never been this way before; ain’t it grand.’”

This Issue

April 23, 2020

Like No One They’d Ever Seen

Resistance Is Futile

The Brilliant Plodder

-

1

That interview appears in Rainer’s valuable book A Woman Who…: Essays, Interviews, Scripts (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999). ↩

-

2

Included in The Disintegration of a Critic, a much-needed new anthology of Johnston’s writings edited by Fiona McGovern, Megan Francis Sullivan, and Axel Wieder and published last year by Sternberg Press. ↩

-

3

See Malik Gaines, “Real People,” in Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, edited by Ana Janevski and Thomas J. Lax (Museum of Modern Art, 2018); and Carrie Lambert-Beatty, Being Watched: Yvonne Rainer in the 1960s (MIT Press, 2008), an essential book-length account of Rainer’s early dances. ↩

-

4

“Presence at the Creation,” Artforum, Vol. 57, No. 1 (September 2018). ↩

-

5

We take inspiration here from Risa Puleo’s insightful essay “Sitting Beside Yvonne Rainer’s Convalescent Dance,” Art Papers, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter 2018–2019). ↩

-

6

See Douglas Crimp, “Pedagogical Vaudevillian,” in Yvonne Rainer: Space, Body, Language, edited by Yilmaz Dziewior and Barbara Engelbach (Museum Ludwig, 2012). ↩