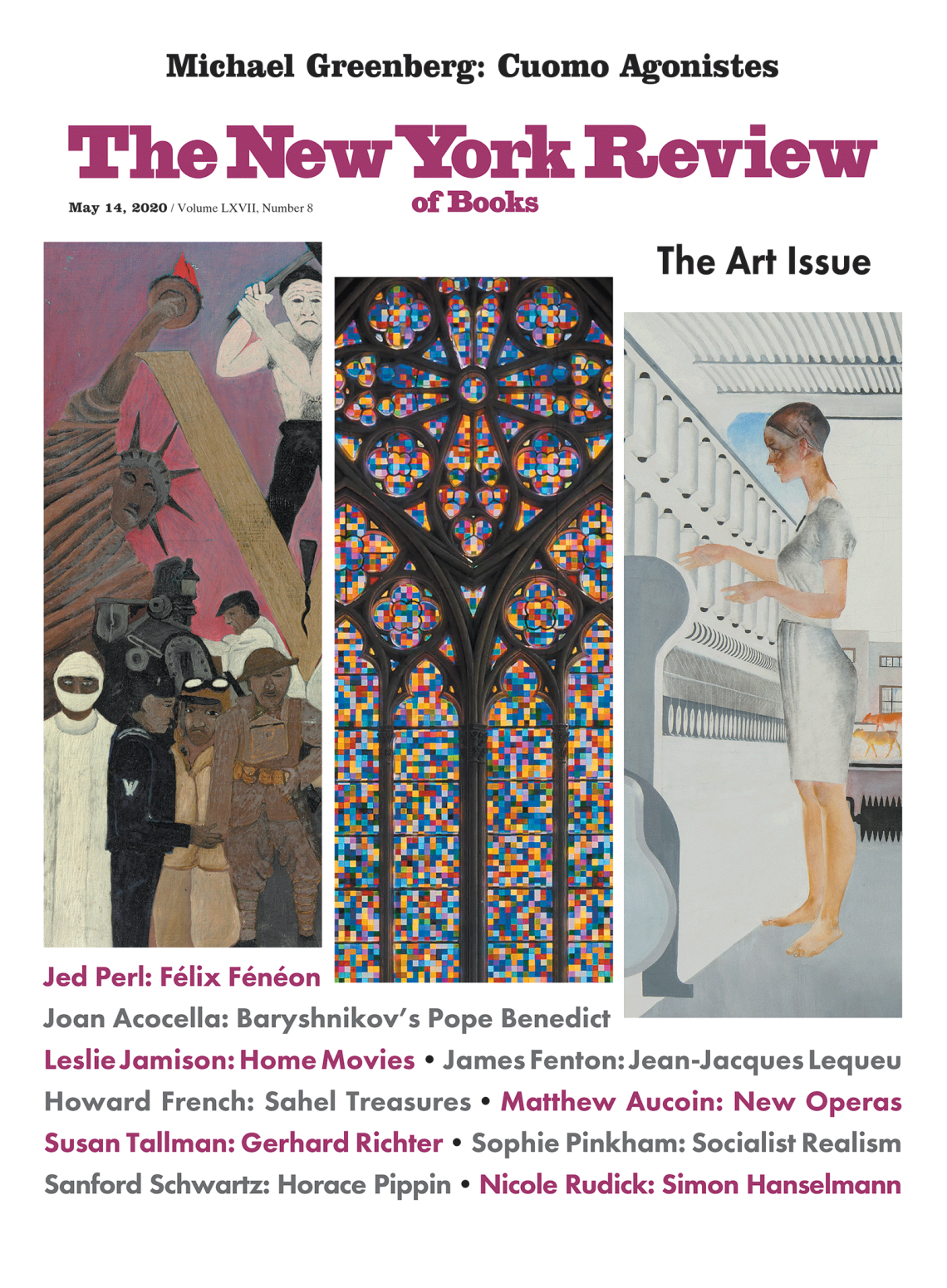

In 2002 Gerhard Richter was included in a conversation about the restoration of the great gothic cathedral of Cologne. The building had survived the “thousand-bomber” raids that flattened the city in 1942, but the stained glass of the enormous tracery window in the south transept had been lost, and the cathedral chapter now wanted to replace the plain-glass postwar repairs with something that lived up to the building’s spectacular presence and spiritual purpose—ideally, a work by a major artist, commemorating victims of Nazism.

Richter was, in one sense, an obvious choice—one of Germany’s most prominent artists, he had lived in Cologne for years. In other ways, the decision was curious. Richter is not religious, and while his work had made glancing references to the Third Reich, his position on the often reflexive commemoration of war crimes was not uncomplicated. For the cathedral, he considered, then rejected, the possibility of transmuting Nazi execution photographs into stained glass. Instead he turned to a 1974 painting of randomly arranged color squares, part of a series that had included paintings, prints, and a design for commercial carpeting. Cologne’s archbishop, who had wanted something demonstrably—even exclusively—Christian, did not attend the unveiling.1 But while Richter’s window is, in theory, a reprise—its approximately 11,500 color squares were arranged by algorithm and tweaked by the artist to remove any suggestion of symbols or ciphers—the experience it provides is utterly distinct. The squares are made of glass using medieval recipes, they rise collectively some seventy-five feet, and are part of a gothic cathedral. When the sun shines through and paints floors, walls, and people with moving color, the effect is aleatoric, agnostic, and otherworldly. It should mean nothing, and feels like it could mean everything.

Decades earlier, fresh from two rounds of art school—one in East Germany, one in West—Richter had made a note to himself: “Pictures which are interpretable, and which contain a meaning, are bad pictures.” A good picture “takes away our certainty, because it deprives a thing of its meaning and its name. It shows us the thing in all the manifold significance and infinite variety that preclude the emergence of any single meaning and view.”

Richter is contemporary art’s great poet of uncertainty; his work sets the will to believe and the obligation to doubt in perfect oscillation. Now eighty-eight, he is frequently described as one of the world’s “most influential” living artists, but his impact is less concrete than the phrase suggests. There is no school of Richter. His output is too quixotic, too personal, to be transferrable as a style in the manner of de Kooning or Rauschenberg. Though his influence has indeed been profound, it has played out in eyes rather than hands, shifting the ways in which we look, and what we expect looking to do for us.

In Germany he is treated as a kind of painterly public intellectual—personally diffident and professionally serious, a thoughtful oracle especially as regards the prickly territory of German history. He was among the first postwar German artists to deal with pictorial records of Nazism, and his approach to the past might be summarized as poignant pragmatism, rejecting both despair and amnesia. One measure of his status is that visitors today enter the Reichstag flanked by two soaring Richters: on one side a sixty-seven-foot glass stele in the colors of the German flag; on the other, facsimiles of Birkenau (2014), the paintings through which he finally succeeded in responding to the Holocaust, abandoning earlier attempts across five decades.

The Birkenau paintings, which had never been seen on this side of the Atlantic, were among the eagerly anticipated inclusions in “Gerhard Richter: Painting After All,” the last exhibition to be held at the Met Breuer before the building is ceded to the Frick Collection in July. A streamlined, eloquent summa of Richter’s career, curated by Sheena Wagstaff and Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, the show opened on March 4, nine days before being shuttered by Covid-19 (along with a concurrent exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery). I’m one of thousands who missed that brief window. It is not yet known whether the show will reopen in New York before it travels to Los Angeles in August. In the meantime, we are left with an expansive website (the museum has posted images of all works in the show, installation shots, and some film clips), a weighty catalog, and memories of works seen in person. This is, of course, not ideal: many of the things shown depend on properties of scale and reflectivity that cannot be experienced in reproduction. But this is a retrospective about retrospection, and the situation is not without a certain resonance.

The opening wall is a preview of the elliptical path taken through Richter’s career. Table (1962), the first painting Richter put into his catalogue raisonné, is a mix of Pop-ish consumer culture (the titular subject was clipped from an Italian design magazine) and ersatz expressionism (it devolves at the center into circular sweeps of paint thinner). Eleven Panes (2004), forty-two years younger, is a leaning stack of eleven-foot-tall sheets of glass, individually transparent but collectively reflective, windows ganged up to make a stammering mirror. The small photo-painting September (2005) bears a discreet echo of Table’s inchoate mess in the desolate cloud leaking from the South Tower on September 11; the brash colors of the source photograph have been drawn down, the orange of the explosion scraped away, time hovers like a bee, neither frozen nor moving forward. Even in reproduction, the arrangement of these works is affecting: three visions of the world being unmade and made again. In real life, this idea would be further extended by the ephemeral animation of passersby reflected in the glass. The installation photographs, however, were cleverly constructed to conceal the photographer in the mirror—an uncanny absence that evokes the emptiness of public space in Covid-time.

Advertisement

American audiences came late to Richter. In the 1960s and 1970s the hegemony of American Pop, Minimalism, and Conceptualism tended to crowd out curiosity about what was going on elsewhere. Richter’s first solo show in New York in 1973 did not ignite great excitement, and for many years he was understood here primarily as a graphic artist; his first interview in the American press appeared in The Print Collector’s Newsletter in 1985.2 By then, a series of influential exhibitions (as well as favorable exchange rates for American dealers and collectors) had stoked new interest in European art, but Richter’s reputation lagged behind those of Germans such as Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer who made raw work that spoke of war and atonement in no uncertain terms.

Richter’s oeuvre, by contrast, was measured and indirect and took a confusing variety of forms. His foggy photo-paintings suggested an oxymoronic lugubrious Pop, the random color squares an ebullient Conceptualism, and his soft-focus landscapes and portraits channeled both the Sturm und Drang of German Romanticism and the cool distance of contemporary photography. Uncertain terms were Richter’s métier, and critics simply did not know what to do with it. Many concluded he was a cynic bent on invalidating art itself: “Richter wars on poetries,” declared a 1989 review in The Washington Post. “When he depicts a cloudy sky, or a log fence and a red-roofed barn in the quiet countryside, he somehow makes you queasy.” Even admiring critics like Peter Schjeldahl acknowledged Richter’s reputation for “severity, hermeticism, and all-around, intimidating difficulty.”

It was not until the 2002 Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting,” organized by Robert Storr, that American audiences really warmed to Richter. He was then seventy years old, and the emotional hypervigilance of his early work had softened. American viewers had also matured: the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of that hopeful experiment in peace and prosperity, the European Union, bathed Germany in a more benign light than it had enjoyed in the anglophone world for a century. The photo-paintings now looked plangent rather than snide; the multivalent shifting of styles was recognized not as sarcasm but as a defense against dogma; the portrait of his daughter turning from the camera (Betty, 1988), hushed and luminous, made no one queasy. His peculiar breadth was evidence of a patient regard for the world. Richter, it turned out, was a mensch.

“Painting After All” recapitulates this history (indeed, it features many of the same paintings), while extending the timeline both later and earlier. The show’s interest in memory is visible through groupings and inter-gallery vistas that illuminate continuities and repetitions across time. The catalog takes a more didactic approach, and how you feel about it probably depends on how you feel about Buchloh, Richter’s long-time interlocutor (though the two have famously disagreed about some of Buchloh’s conclusions) and an art historian deeply entrenched in Frankfurt School social theory and philosophical postulates. Perhaps because of the wealth of Richter literature already in the world, the text bypasses the usual career overview; each of its seven authors (all but one quotes from Buchloh) targets a specific subset of works. This has the advantage of illuminating some less-visited corners of Richter’s oeuvre (Hal Foster’s discussion of the glass works and Peter Geimer’s pocket history of German abstract photography are particularly useful), though readers new to Richter may feel like they’ve accidentally enrolled in the second term of a class in which every other student has taken the intro.3

Richter’s biography matters—not because he has made it the subject of his work (he has not), but because the historical systems and events he has lived through have directly informed the way he thinks about art and about history. Born in Dresden in 1932, he grew up in smaller towns along the Polish border during World War II. In postwar East Germany he received a rigorous technical training at the venerable Dresden art academy, but had only limited exposure to modern art: “We weren’t able to borrow books that dealt with the period beyond the onset of Impressionism because that was when bourgeois decadence set in.” (Only one work from this period, a remarkably prescient series of monotypes, is included in Richter’s official catalog; it was on view in facsimile form at both the Met Breuer and Marian Goodman.) After some early success as a painter of affirming Socialist Realist murals, he was permitted to travel to West Germany in 1959 to visit the second Documenta exhibition in Kassel, where he encountered paintings by Lucio Fontana and Jackson Pollock that upended everything he knew about pictures. Two years later he defected to the West, writing to his favorite professor in Dresden, “mine was not a careless decision based on a desire for nicer cars.”

Advertisement

Düsseldorf, where he reenrolled in art school, was a world apart from the monoculture of official East German art: Beuys had recently arrived with his mystical cult of personality, the Zero group was developing its language of impersonal geometries, and Informel (Europe’s attenuated answer to New York School abstraction) was championed as the subjective antidote to totalitarianism and its instrumentalizing of soppy figuration. Even in the West, artistic style was a badge of political allegiance—abstract/universalist vs. figurative/populist. And both Germanies, focused on building their respective new societies, chose not to ruminate on the unprecedented destruction perpetrated by—and inflicted on—their people. It would not be until the cusp of the millennium that W.G. Sebald’s On the Natural History of Destruction anatomized the silence around the German civilian experience of the war: “When we turn to take a retrospective view,” Sebald wrote, “we are always looking and looking away at the same time.”4

Among the group of young, irreverent artists Richter met in Düsseldorf was Sigmar Polke, who for several years provided a crucial, puckish complement to Richter’s circumspection. Discarding the various high-minded models around them, Polke and Richter began painting from newspaper clippings and magazines, toying with the ways mechanical reproduction remakes its subjects—the flattening and fragmentation of cheap printing and the unseemly croppings and juxtapositions of the commercial printed page. The stupidity of copying was part of the irreverence—serious modern art is supposed to despise the copy. But copying, done attentively, is a way into something. Academic art training depended on it as a means of internalizing the canon, but even as children we copy something when we can’t get it out of our heads. Richter began keeping photographs, clippings, and sketches of potential source material that would become Atlas, his now career-long half-archive, half-artwork of things “somewhere between art and garbage and that somehow seemed important to me and a pity to throw away.”

Most of Richter’s subjects appeared affably Pop—families by the seaside, tabloid perp walks, household goods—but where Pop Art tended to ratchet up the volume with brighter colors and sharper edges, Richter turned the dial in the other direction, painting everything in plaintive grays with a subaqueous wobble. And the subjects were not all as banal as they seemed. Scattered amid the race cars and drying racks were bombers dropping their payloads and family members destroyed by the Third Reich: Uncle Rudi (1965), smiling jauntily in his enormous Wehrmacht overcoat, later killed in combat; Aunt Marianne (1965), shown as a teenager with the infant Richter, years before she was institutionalized as a schizophrenic and starved to death by the Nazi Aktion T4 “euthanasia” of the “unfit.” Richter’s paintings of Rudi and Marianne are no more or less anguished than his ones of kitchen chairs. But for German viewers in the 1960s they must have invoked numberless pictures of relatives—victims, villains, heroes—removed from display as markers of a world best not mentioned.

By the 1970s Richter had also become intrigued with the possibilities of pictures that originated not in a preselected image, but in an a priori set of rules. The random color squares that later dappled worshipers in Cologne Cathedral were one result; a body of heavily impastoed canvases made by moving paint around in semi-predetermined ways was another. This edging toward Conceptualism did not mark an abandonment of representation, however. He continued making paintings from photographs, now usually his own, including color landscapes so refulgent they might, in thumbnail, be mistaken for Turners. Some of these were tricks, painted from photomontages that unravel as you look. Others, like his lit candles and misty skulls, balanced reality and Romanticism on a knife’s edge.

Gradually Richter’s art-historical allegiances were laid bare: Caspar David Friedrich, Vermeer, Velázquez—painters with a gift for inviting us through the illusory window while showing us how the trick was played (the oversized sequins of light that Vermeer scatters on metalwork and bread rolls call attention to the materiality of paint as surely as any Pollock drip). In the portraits of his friends and family especially one senses the double desire to capture the emotional load of a moment and to reveal the means by which image turns into feeling. When things slip too far toward tender, he adjusts the surface with lateral swipes of paint or abrasions, pushing and pulling until that magical space between looking and knowing is reached.

Academic writers often view Richter as a master strategist plotting from on high, but his own statements suggest something less mandarin: “It is my wish,” he told Storr, “to create a well-built, beautiful, constructive painting. And there are many moments when I plan to do just that, and then I realize that it looks terrible. Then I start to destroy it, piece by piece, and I arrive at something that I didn’t want but that looks pretty good.” In 1980 he began using squeegees to drag paint in broad, uneven swaths that partly obscure whatever lies below—photographs, printed matter, prior paintings. It’s the look of mechanical failure—machine parts wearing badly, jammed printers, skid marks, abraded film. When repeated over and over, it generates complex color fields full of fissures and pockets exposing older strata. Geological metaphors feel apt—the surfaces resemble landscapes shaped by the scouring and dumping of glaciers. Richter has limited control over what happens in any one layer, so composition becomes the joint product of accumulation and knowing when to stop.

“Sometimes I think I should not call myself a painter, but a picture-maker,” Richter remarked in 2013. “I am more interested in pictures than in painting. Painting has something slightly dusty about it.” I suspect it is not painting’s long history that bothers him, but a more specific quality. Dust accumulates on things that are settled, immobile. And painting, in our culture, has the unassailable fixity of a monument. It’s a property Richter has repeatedly undermined, cutting up paintings and distributing the pieces as editions, rereleasing finished paintings as photographic editions and digital facsimiles under Plexiglas. (The Aunt Marianne in “Painting After All” is not, in fact, a painting.) Like Jasper Johns, his near contemporary, he is fascinated by doubling, mirroring, and illusion—the same-not-same quandary of image and object. His many prints, facsimiles, and artists books are not so much spin-offs of his paintings (though that is how they are often regarded) but partners with painting in a bantering, ongoing conversation. Even the persistent doubling back and restructuring of earlier work can be seen as a corrective to the presumed finality of painting.

One squeegee painting from 1990, Abstract Painting (#724-4 in his catalogue raisonné), has been repeatedly reformulated: resized and defocused in photographic editions, digitally refracted as kaleidoscopic tapestries and stained glass windows for a sixth-century monastery in rural Saarland, and slivered in a Photoshop version of Xeno’s paradox for the series called Strip. (The image was digitally bisected and mirrored; those halves were each bisected and mirrored, then those quarters, and so on, to produce 4096 (212) segments, each less than 100 microns wide, that fuse together in the eye to produce a pattern of stripes. These patterns were then cut up, arranged in different orders, and printed at different sizes.) The Strip in “Painting After All” runs an optically dazzling thirty-three feet across.

The monumental painting sextet Cage (2006)—also in the US now for the first time—started out as photo-paintings of scientific images of atoms (resembling fuzzy photographs, these are records of particle behavior translated into light and dark to accommodate human sensibilities). Having committed the pictures to canvas, Richter found himself bored by the result and began adding color, painting in and scratching out. At the end of four months, the atom arrays were present only as an inherited rhythm within the complex accretion of paint. In its grandeur of agitation and resolution, Cage may be as close to the sublime as contemporary painting can get. Perhaps it was to knock the dust off that sublimity that Richter followed up with two facsimile editions, breaking Cage 6 into sixteen parts that can be carried in a flight case and hung in any configuration that suits the owner.

Everything, Richter demonstrates, is a derivative, everything is contingent, nothing is immutable. This has implications for how one thinks about history. Even about catastrophes.

The Birkenau paintings are also abstract responses to failed photo-paintings, but the underlying images are of a different moral order: four photographs taken clandestinely in late summer 1944 by Sonderkommando prisoners forced to work in the gas chambers and crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The ethics of using, exhibiting, or even viewing Holocaust photographs has always been complicated. Moving east with American troops in 1945, Robert Capa declined to use his camera: “From the Rhine to the Oder I took no pictures. The concentration camps were swarming with photographers, and every new picture of horror served only to diminish the total effect.” As early as the spring of 1945, Peter Geimer explains in the catalog, the Allies began circulating camp photographs in Germany, but the anticipated ethical shock never materialized, and the pictures disappeared. Richter remembers being shown them for the first time by a fellow student in Dresden in the mid-1950s: “It was like irrefutable proof of something we had always half known.”

Shoah director Claude Lanzmann objected not just to the numbing effects of profusion, but to visual representation itself—the illusion of a presence when the reality was one of appalling absence. The opposing view, voiced by Jean-Luc Godard and others, was that documents are our strongest defense against amnesia, and that images can be powerful agents of imaginative reconstruction. (Whether or not imagination should have a role here is the heart of the conflict.)

As the only pictures taken by victims of the killing system they document, the Sonderkommando photographs occupy a special place in this debate. In 2001 the French art historian Georges Didi-Huberman wrote an essay for an exhibition in which they were shown and was roundly attacked in the pages of Lanzmann’s journal, Les temps modernes. Didi-Huberman responded with a carefully considered book, Images malgré tout, which Richter read in Geimer’s German translation, Bilder trotz allem. In English the title is Images in Spite of All, but the German can also be translated as “Painting After All.”

The Sonderkommando photographs are unique not only because of who took them and what they show, but because of their appearance. They had to be shot secretly from a distance and are hard to read. Two of them look out through an angled trapezoid of doorway onto a landscape where people are working by a bonfire, smoke rising against silhouetted trees. It takes a moment to register the barbed wire and to understand that the things piled on the ground are not logs but bodies. The other two photos show tree trunks at a sharp angle. One is a misfire—just black trees and white sky. But one includes a wedge of land over which small figures—naked women—are walking or running. Reconstructions show that they are headed to the gas chambers and that the bonfire pictures were shot from within one of the gas chamber buildings.

The human element is overwhelming once recognized, but it occupies only a small area and reveals itself slowly. The pictures’ initial impression is one of visual dynamism, modernist angles slamming into tropes of Friedrich-era Romanticism: soaring trees, billowing vapor, nature seen through a doorway. Perhaps because of the paradoxical way form and content cut across each other here, Richter felt it might be possible to make them into paintings. He flipped them left-right, projected them, and transcribed them onto canvas.

Their failure as photo-paintings has, I think, nothing to do with visual quality and everything to do with history. Richter’s photo-paintings work because, no matter how intimate the subjects, they function as types. Individuals and events are elided, commonalities revealed, through a concentration on form. Even his elegiac paintings of dead Baader-Meinhof members are as much about the dislocating formats of news as they are about the wasted lives in question. Given the Sonderkommando photographs’ singular status as historical documents, however, they cannot be stand-ins for anything else—not for the look of clandestine photography, not for “man’s inhumanity to man,” not for German accountability. They do not work as “pictures” in Richter’s sense of precluding “the emergence of any single meaning” or “depriv[ing] a thing of its meaning and its name.” Here, meaning and name are untouchable.

Richter did not abandon the images but, as with Cage, began working into and over them, pulling paint horizontally and vertically, layer upon layer. The Met website shows the progression from source photo to drawing, to photo-painting, to successive states of overpainting. The final canvases have the tenor of a forest after a fire—twitchy, ashy crusts over an underworld of dun, crimson, and kelly green. They are complex, scarified, and also—here’s the rub—beautiful. In places the juddering repetition of fragmented color recalls, of all things, late Monet water lilies.

Max Glickman, the Holocaust-obsessed cartoonist in Howard Jacobson’s novel Kalooki Nights, captures the moral vertigo induced by the collision of aesthetics and the Holocaust: “A mass grave at Belsen—the bodies almost beautiful in their abstraction, that’s if you dare let your eye abstract in such a place.”5 Perhaps to brace us against that fall, Richter has gone to some lengths to structure how we experience the paintings. They do not stand alone. The original photographs are hung on an adjacent wall, in prints small enough to be understood as documents, and large enough to be legible. There are sources and there are commentaries, Richter tells us, events and reverberations of those events. More eccentrically, he has doubled the paintings themselves. The four canvases hang opposite four full-scale not-quite doppelgängers, each divided into quarters. Source, commentary, and gloss.

The events of 1944 are beyond our reach. The subject of these paintings is not that world, but our own—the place where we actively choose to know or not know, see or not see. At the Met Breuer, the whole confab of paintings, facsimiles, and historical photographs is further multiplied by a thirty-foot-long stretch of gray mirrors at the back—Sebald’s “looking and looking away at the same time” made inescapable.

The writer William Maxwell, who, like Richter, was a habitual spinner of fictions that were barely fictions, once had a (barely fictional) character observe:

What we, or at any rate what I, refer to confidently as memory—meaning a moment, a scene, a fact that has been subjected to a fixative and thereby rescued from oblivion—is really a form of storytelling that goes on continually in the mind and often changes with the telling. Too many conflicting emotional interests are involved for life ever to be wholly acceptable…. In any case, in talking about the past we lie with every breath we draw.6

Richter’s oeuvre is, at some level, a six-decade-long disquisition on this lie—its inevitability, its emotional utility, its shape-changing instability. His stylistic tics—the hazy edges, overlaying, chopping into pieces, and reconfiguring of parts—are visual reminders that you are not seeing everything, that availability to the eye is no guarantee of clarity. The story always changes with the telling. Uncertainty is truth.

Fair enough. But what is perhaps most remarkable about Richter’s art is its affirmation that this is not a bad thing. The story of the color-square painting that became a carpet that became a cathedral window (and now, undoubtedly, somebody’s cell phone wallpaper) is not a tragedy, it’s an assertion of endless possibility.

This Issue

May 14, 2020

Vector in Chief

Realists of the Soviet Fantasy

-

1

The Cologne Express quoted Archbishop Joachim Meisner as saying, “The window does not fit the cathedral. It would fit better in a mosque or a prayer house…. If we get a new window, it should be a clear reflection of our faith, not just any faith.” ↩

-

2

Dorothea Dietrich, “Gerhard Richter: An Interview,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter, Vol. 16, No. 4 (September–October 1985). ↩

-

3

For the curious, the artist’s website provides an admirably thorough catalogue raisonné, as well as biographical essays, bibliographies, and other source material. See gerhard-richter.com. ↩

-

4

W.G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction (Random House, 2003), p. ix. ↩

-

5

Howard Jacobson, Kalooki Nights (London: Vintage, 2007), p. 80. ↩

-

6

William Maxwell, So Long See You Tomorrow (Vintage, 1996), p. 27. ↩