Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar may be the most famous evocation of depression in fiction. The fullness of Esther Greenwood’s mental illness is slow to reveal itself, to the characters and to the reader, masked in part by her intellect and caustic wit, as well as her deceptive ability to move through life while not taking part or pleasure in it. “I wasn’t steering anything, not even myself,” Esther says. “I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.”

After a stint in the New York publishing world, Esther returns home to Massachusetts for a summer in the “escape-proof cage” of suburbia. She spies on a neighbor from the window of her bedroom one morning and then hides, in a minor paranoid fit, when she thinks the neighbor might see her: “I crawled back into bed and pulled the sheet over my head. But even that didn’t shut out the light, so I buried my head under the darkness of the pillow and pretended it was night. I couldn’t see the point of getting up. I had nothing to look forward to.” This scene lasts a moment, but imagine Esther spending almost the entirety of the novel brooding peevishly in her bedroom and you have some sense of what it feels like to spend time with Simon Hanselmann’s comics.

The inertia and stagnation Esther feels and the increasingly circumscribed life she leads before treatment are common territory for Megg, the primary character in Hanselmann’s ongoing Megg and Mogg series, begun in 2009 and comprising four book-length collections to date.1 In Hanselmann’s telling, depression hits a low register and stays there, both ambient drone and narrative pulse. Megg spends most of her time inside and relies on welfare to get by. She takes antidepressants and sees a therapist, but these measures barely keep her afloat in a sea of unhappiness.

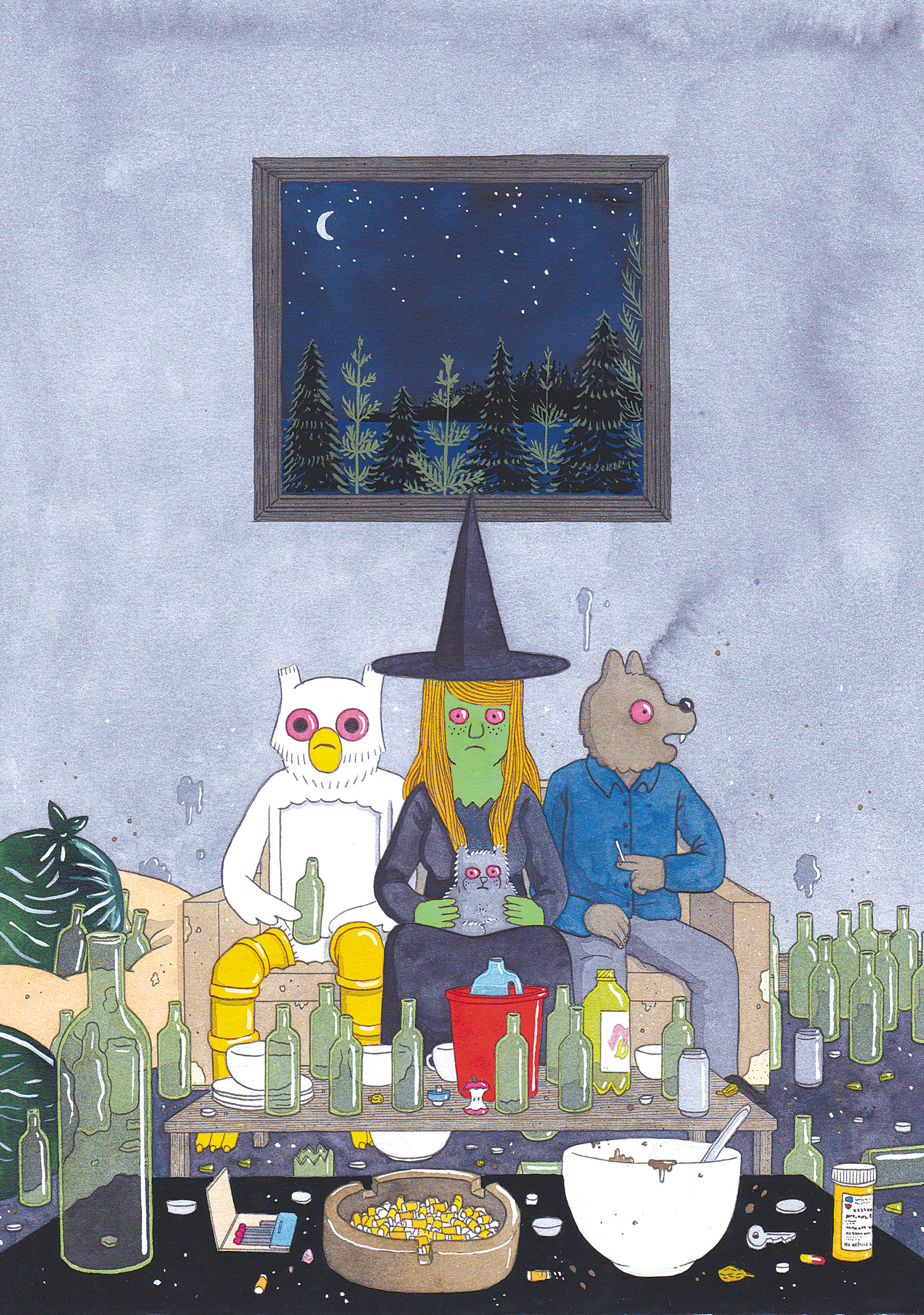

In all other ways, the Megg and Mogg comics, set in a nondescript, working-class suburbia, couldn’t be more different from Plath’s middle-class New England novel. For starters, Megg is a witch—the green-skinned, pointy-hat type (though in keeping with the comic’s theme of mundanity, she does not practice magic). Mogg, her roommate and boyfriend, is a Garfield-shaped black cat (the joke is that if Mogg is Megg’s familiar, it is in the sexual sense, rather than the pagan one). These characters, friends from high school who are now in their twenties, are loosely based on a series of children’s books from the 1970s written by Helen Nicoll and illustrated by Jan Pieńkowski, called Meg and Mog, which Hanselmann read as a child. The series also featured a white owl, who appears in Hanselmann’s work as Megg and Mogg’s beleaguered roommate Owl, who is still an owl but an anthropomorphized one with all the problems and anxieties of a real adult.

Hanselmann’s comics are entirely adult. The sour air in which Megg stews is the musky stank of pot smoke. She and her friends consume drugs and alcohol in great quantity and variety, engage in dumb pranks and buffoonery around their small town, and are mutually abusive. They are consistently broke; inventing schemes to make enough money to buy weed is a common start to many of their misadventures.

Like any first-rate stoner comedy, these comics merge humor and derangement (and in doing so, harken back to comics’ roots in enthusiastic and subversive absurdity2). In Megahex (2014), Hanselmann’s first collection, Megg and Mogg devise an elaborate late-night plan to break into a closed deli for food in order to avoid walking to a restaurant, and then, panicked, concoct an equally elaborate plan the next morning to buy the same food from the same deli to cover their tracks. In Bad Gateway (2019), Hanselmann’s latest book, Megg breastfeeds a crow and pretends to give birth to another in front of her welfare caseworker in a bid to maintain her benefits, and Mogg gets fired from a cat café when a customer’s attention gives him an erection. (In all fairness, the job is exploitative. “Make yourself available to our guests…. Flirt a little. Try to smile,” his employer advises.) In another story from Megahex, Owl arrives home after a difficult day at work. Megg and Mogg, usually stingy with their weed, treat him to a smoke and then drive him through a rainbow car wash, which they all perceive as a hallucinogenic light show. “I think this makes me feel actual happiness,” Owl says in the final panel.

Little background is given until later volumes, and the characters only accrue depth over the long course of the series. The dynamics between them are Hanselmann’s foremost narrative tool. In this respect, the comics resemble traditional gag-based strips that rely on changing themes and subjects and characters who remain steadfastly the same. Megg swings between narcotized misbehavior (by turns gleeful, indifferent, and anxious) and blank depression. Mogg is needy and manipulative; his small size relative to the other characters sometimes feels like a gloss on his importance to the group at large. Owl’s uptightness, passivity, and ineptitude frequently amplify his misfortune at the hands of his friends. His visual signifiers are a tie, a briefcase, and some combination of sweat, tears, and blood. Their collaborative dysfunction is best summarized by Mogg, who calls them “a three person couple.”

Advertisement

Hanselmann has referred to the interconnected Megg and Mogg stories as “episodes” and the comic at large as “a sitcom on paper.” There is a surface affinity to TV comedy—many of the individual stories, which range in length from a single page to more than twenty, could function as standalone works—but unlike a traditional sitcom, Hanselmann’s comics are more than the sum of their parts, and stories that finish on a low note rather than a laugh-track high undermine his own neat comparison.

These stories veer into dark territory, with the characters chafing against the strictures of the strip/sitcom structure. Owl is victimized in nearly every story in which he appears, through intense ridicule, practical jokes, or more sinister acts. Not long after the car-wash adventure, Owl lands his dream job, an undefined middle-management office position. His elation inspires Megg and Mogg to concoct a cruel prank. They reset his alarm, hide all of his pants, and induce him to have a wet dream. He wakes late the next morning and must race to the office in the sullied pants he slept in. When he arrives, sweaty and soiled, he is promptly fired. The end of the story finds Owl retreating under a bridge with his briefcase and a bottle of vodka. Megg and Mogg appear, also with a bottle of vodka. “What ‘peas in a pod’ we are!” Megg smirks, a reminder that ambitions such as Owl’s are disallowed in their circle.

In a one-pager near the beginning of Megahex, Megg dances alone in her room, in her underwear, and sings along to Kate Bush’s trilling, transporting song “Wuthering Heights.” In the fourth panel, Mogg’s eyes peer around the door as Megg careens freely and unaware. The last panel shows only Mogg, the voyeur, his penis erect. If this is a joke about the witchiness of Bush’s song, it is also a betrayal of and an assault on Megg’s unburdened joy. Toward the end of the book, her depression comes into full view in a two-page story. The first page reproduces the same image—a closeup of Megg’s face as she lies in bed staring at the ceiling—in six panels; the seventh introduces stray black lines that snake above her head. The panels on the second page reveal the totality of the scene: three large, sinister heads, framed by twisting black wisps of hair, vomit a black liquid that pools on the floor around Megg’s mattress. Beset by this horrific hallucination, she lies frozen until the room is consumed by blackness.

The comic is most disturbing when the copious drug use combines with graphic representations of sex, as they do through the dissolute character of Werewolf Jones, a werewolf for whom every day is a debauch of indiscriminate sex and narcotic abuse. He appears only intermittently in Megahex, but once he becomes a prominent character, in Megg and Mogg in Amsterdam (2016), Hanselmann’s second book, the dynamic shifts from puerile to lurid. A story from the third collection, One More Year (2017), revolves around Werewolf Jones’s performance of a bodily-function act called a “Boston clanger,” about which the less said, the better.

The most humane character is Booger, a transgender bogeyman who is also briefly introduced in Megahex and becomes a more regular character in Amsterdam. In Booger, Hanselmann draws on the all-too-common analogy of transgenderism and monstrousness, but then unravels the conceit. Booger is never a gag; she is the most emotionally honest of Hanselmann’s characters, her role deepening as the comics develop. Most of the time, she is the only other female character in the stories and an essential element in Megg’s growing dissatisfaction with the state of her life as well as a love interest.

Hanselmann’s frugal treatment of Megg’s crushing depression among the funny grotesqueries of the strange group’s daily life is what makes these comics at once entertaining and potent. Without the psychological element, the stories would be a kind of arty Jackass; absent the over-the-top, frequently repulsive hijinks, the depth of Megg’s illness wouldn’t be as keenly perceived. Neither comes at the cost of the other: humor doesn’t transmute into melodrama, and desolation is never a punchline.

Advertisement

Hanselmann, who was born in Tasmania in 1981 and now lives in Seattle, began publishing his Megg and Mogg stories in zines and then as a web comic on Tumblr in 2012. At age thirty-one, he published Megahex, which gathers thirty-five stories written and drawn between 2009 and 2014. The more complex of these, like the aforementioned deli caper, run to a dozen pages or more and involve an act of negligence or mischievousness that goes awry, cascading into a series of slapstick mishaps that finish in a violent denouement. These well-plotted sequences have the irresistible allure of a car crash—the measured unfolding of events abstracts the inevitable calamity.

Other stories in the book keep to a page. In one of these economical stories, Hanselmann uses four panels to set up a prank in which Megg gives Owl a wedgie. Owl makes his lunch and leaves the kitchen as Megg and Mogg peek around a corner. When Megg carries out the practical joke, it backfires. Owl’s underwear rips, and Megg is left holding the tatters. Both are surprised, and their wordless mutual shock endures through the comic’s last two panels. Hanselmann provides no reconciliation, no parting shot, only the quick shock of the unexpected. He forgoes the amiable discomfort of the classic gag scenario, instead stranding his characters, and the reader, in uncharted territory.

This sort of approach worked to great effect in Dan Clowes’s Wilson (2010), which tells the story of the titular character—a middle-aged cynic and sociopath on a failed quest for human connection—by way of seventy one-page gag strips. The strips end almost exclusively with spiteful zingers that instantly undo any goodwill the reader may have felt for Wilson, or the characters for one another. Clowes and Hanselmann may share a spleen. In his Dan Pussey stories, serialized in the comic Eightball from 1989 to 1994, Clowes parodied contemporary comics figures, such as Art Spiegelman and Stan Lee. Hanselmann did something similar in Truth Zone, his online comic published from 2012 to 2014, which skewered numerous independent cartoonists, including Clowes, and the industry at large. Another of Hanselmann’s splenetic forebears is Peter Bagge, whose 1990s comic Hate—which Hanselmann started reading at the age of thirteen—occupies the same dead zone of delayed adulthood for a gang of potheads, depressives, and jerks.

Two of Hanselmann’s books—Megahex and Megg and Mogg in Amsterdam—have spent time on the New York Times graphic books best-seller list. He hews to traditional layouts, producing grids of twelve to twenty panels per page, sometimes up to thirty. He is adept at pacing a story, toggling between entropy and excitement, and uses repetition, especially of characters’ faces, to great effect in eliciting a slow anatomy of awful feeling. His drawings are a kind of expressive realism, a beguiling combination of cartoonishness and carefully rendered details and perspectives (the garbage and myriad bottles that litter the group’s living room, or the leafy trees, individual shrubs and plants, architectural elements, sidewalk detritus, and numerous other minutiae that make up any streetscape) lit up by his striking use of watercolor.

The comic’s primary palette is sickly—hot pinks, lime and army greens, shots of blood red and grape-jelly purple, and a generous allotment of drab browns. Occasionally, though, Hanselmann gives way to a more painterly approach, particularly when he sets his characters in natural landscapes. At the end of Megahex, Owl moves out. As he drives away, fireworks explode in the night sky, and he imagines himself flying high above the muted lights of the city, among the pastel bursts and translucent, milky clouds. If there is magic in these comics, it is contained in these small moments: Owl again, standing on the wooded shore of a lake under the moon and a vast sky of stars, or the group, on drugs, plunging through a forest below a pink-and-blue tie-dyed sky, their bodies splashing out trippily behind them as they run.

This last example appears as a painting in the front endpapers of Amsterdam, a moody annotation to the narrative therein. In the back endpapers of Megahex, Hanselmann has painted Megg in the guise of John Everett Millais’s Ophelia, adrift and drowning “as one incapable of her own distress, or like a creature native and indued unto that element,” as Gertrude reports in Hamlet. Megg is so accustomed to the blankness afforded her by depression medication and other drugs that she can’t see her way clear of it. She is pulled into the blackness, into the “mud at the bottom of the brook.” She literally ends up in the muck in Amsterdam. Visiting the city in a desperate bid to resuscitate their relationship, Megg and Mogg throw their meds into a canal. Megg settles into a tentative balance. “I still feel fucking horrible,” she says. “But it’s the nice kind of fucking horrible.” Too soon she tips into delusions and paranoia and dives into the canal to retrieve the pills.

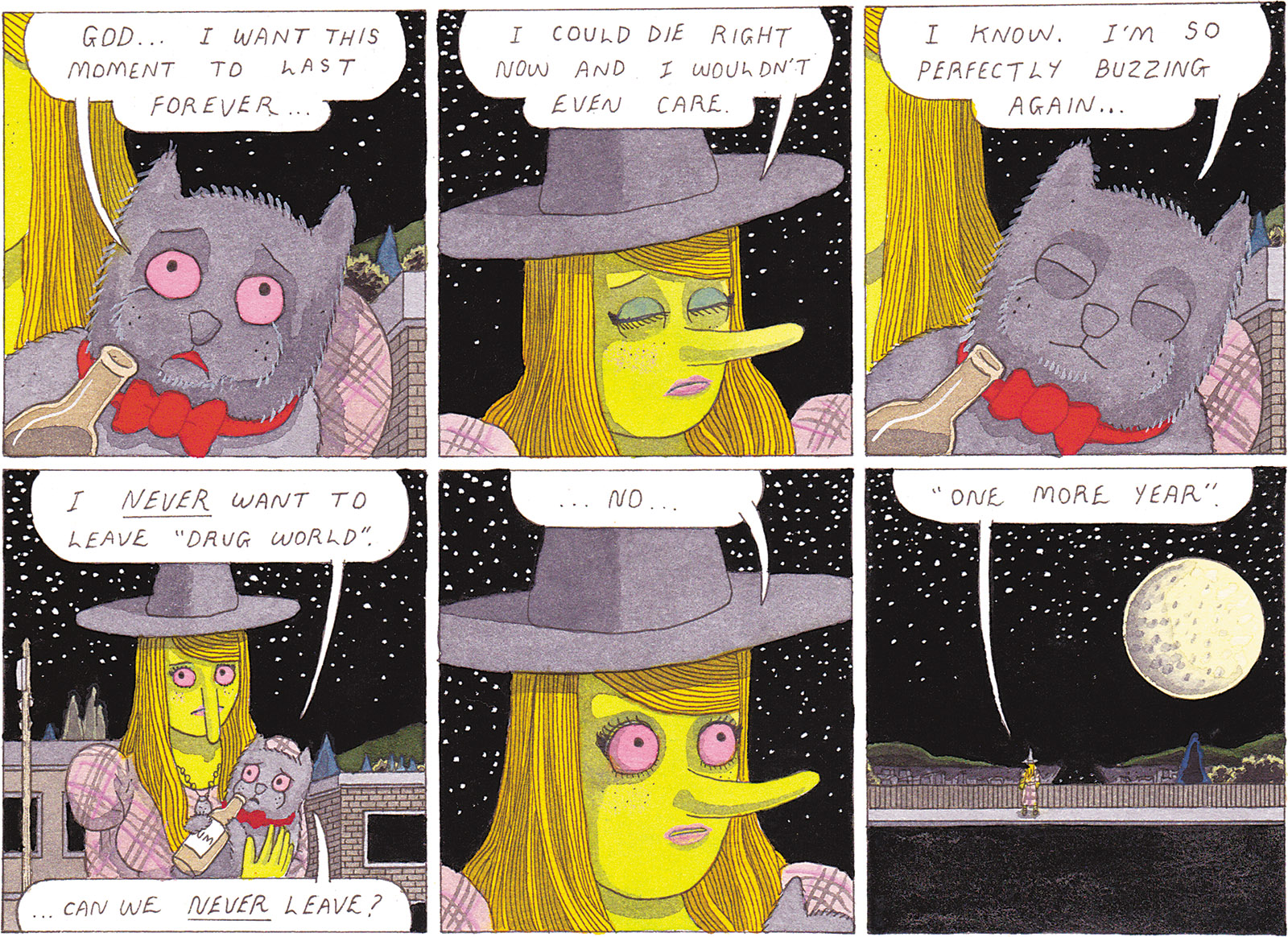

In “Altered Beasts,” a story from One More Year, Megg and Mogg trudge through the night on their way to the engagement party of Megg’s high school nemesis. “It’s such a beautiful sky tonight,” Megg says of the super moon, ponderously suspended in a field of stars. “It looks alive.” Hanselmann renders the moon as an oversize golf ball, pitted and solid. The perilousness of such a lofty feeling is too much for Megg. “I could die right now and I wouldn’t even care,” she says with closed eyes, and then yields to Mogg’s plea that they never leave “drug world.” Megg cannot bring herself to look beyond her miseries; she is captive to them and so prefers the numb safety of addiction to the peaks and valleys of life freely lived.

Depression afflicts all of the senses. In The Noonday Demon, Andrew Solomon likens it to “trying to watch TV through terrible static, where you can sort of see the picture but not really; where you cannot ever see people’s faces, except almost if there is a close-up; where nothing has edges.” Eventually, perception is fully stifled, and nothing is left:

Becoming depressed is like going blind, the darkness at first gradual, then encompassing; it is like going deaf, hearing less and less until a terrible silence is all around you, until you cannot make any sound of your own to penetrate the quiet.

At the end of Amsterdam, Megg despairs of the difficult clarity of sober life. “We’re a family!” Werewolf Jones tells her. “We’re at our best together!” His warm reassurances ring false—in too few stories are they at their best—yet they are a family: dysfunctional, mutually if unhealthily dependent, and devoted to one another. Werewolf Jones’s sentiments are sincere, and the moment is surprisingly tender, but Megg chooses the fog that drugs provide. She swallows a couple of pills, and her surroundings recede. Panel by panel, her vision of her friends is blotted out: they become abstract shapes, then masses of color, before disappearing completely. On the last page, Megg sits alone surrounded by darkness.

Hanselmann describes the small town of Launceston, Tasmania, where he grew up, as “very rednecky, very racist. Very white, very homophobic.” He was abandoned by his father at age two and raised by his mother, an addict and dealer of morphine and various “tablets and stuff” who nonetheless tried, Hanselmann says, to be “a picture-perfect, Hallmark mother.” At school, he was bullied and beaten; he dropped out of high school twice. “It felt like there were just roaming, horrible fucking people who wanted to fuck you up, so you just wanted to stay inside and delve into fantasy,” he told The Comics Journal last year.

Making funny and outlandish drawings brought him a reprieve at school, but the violence and trauma of those years later became fodder for his comics; his characters are both the horrible people and the refugees. Some of his youthful experiences, the hijinks and the abuse, appear in the Megg and Mogg stories, but Bad Gateway parallels his life most directly. When Megg’s mother, a drug addict, mysteriously summons her home, the trip elicits an extended and poignant memory of Megg’s youth, in particular an episode involving her mother, who deals drugs from their kitchen but who also tries to preserve a semblance of normality for her daughter. Megg’s mother is a sympathetic character, a loving parent who fails her child repeatedly. After the DEA raids their home, her mother promises Megg that she won’t let it happen again, only to sell drugs to a teenage Werewolf Jones moments later.

These comics aren’t strictly autobiographical, but it’s fair to say that Hanselmann is very much in them. At a young age, he began dressing up in his mother’s clothes, an experience he recalls as being both thrilling and confusing. Today, he occasionally dresses as a woman and frequently makes public appearances in drag, notably with Megg’s long red hair and freckles. Megg appears in various guises on the covers and in the endpapers of some of the books. At the close of Bad Gateway, for instance, she is “truth coming out of her well,”’ after Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1896 painting. But on its cover, she is modeled on a photograph of Hanselmann himself.

Bad Gateway is billed as a “magnum opus” toward which the three earlier books have been building (Hanselmann plans at least two more books to continue the story). It is the most ambitious of his books, adopting the longer serial installments of, say, a “prestige” television show and ostensibly converging on Megg’s reunion with her mother. But the shift in structure can’t accommodate Hanselmann’s typical narrative tools. The chapters don’t accumulate meaning the way the multiple shorter stories do, nor do they flesh out the narrative in the way the chapters of a novel would. The first three books operate according to high and low intensities, a mix of comedy and despair. But that dynamic range is here drawn out over a longer period, the tone riding in a kind of middle ground, the highs and lows less acute. There is a feeling of gliding through the book to the final chapter, in which Megg arrives at her mother’s—a meeting that has the potential to catalyze Megg’s story. But by then the book is over, just as it seems to have got going.

Megg and Mogg plays on the idea of comic-strip characters who never change, even over long runs—strips like Peanuts and Garfield, whose enduring characters allow for seemingly endless permutations of gags and meditations. Two flashbacks to high school, in One More Year and Bad Gateway, show that Hanselmann’s characters have gotten older but haven’t appreciably changed; they are now only marking time in a different way: reluctant to get jobs, to face their problems, to mature. But time is passing, and pressure is bearing down on them. Hanselmann said recently that he wanted the comic as a whole to be reflective of his own life, specifically the transition from the folly of youth to the burgeoning responsibility, and attendant consequences, of young adulthood. The overarching idea, he said, is “redemption and change and how difficult that is. Breaking patterns and generations of failure.” Plath’s Esther can testify to the difficulty of recovery. In The Bell Jar, even after treatment, she remembers everything, the whole bad dream. “Maybe forgetfulness, like a kind snow, should numb and cover them,” she thinks of her memories. “But they were part of me. They were my landscape.”

-

1

A collection of Hanselmann’s odds and ends, including previously uncollected Megg and Mogg shorts from his self-published zines, will be published as Seeds and Stems by Fantagraphics this August. ↩

-

2

See Art Spiegelman’s essay on the screwball roots of comics, “Foolish Questions,” The New York Review, March 12, 2020. ↩