Pauline Viardot (1821–1910) was one of the most extraordinary women of the nineteenth century. She was raised in a family where, as Liszt put it, “genius seemed to be hereditary.” Her father, Manuel Garcia, born in Seville in 1775, was the first Almaviva in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville (1816). In 1825, with the backing of Lorenzo da Ponte (the librettist for Mozart’s three great comic operas, then teaching Italian at Columbia), Garcia was the first to bring Italian opera to New York City. Viardot’s brother, Manuel, a reportedly indifferent baritone, eventually settled in London, where he became the most famous voice teacher of the day and invented the laryngoscope, a rather nerve-wracking apparatus (I speak from experience) that uses mirrors to allow the vocal folds to be seen in action. Her sister was the fabled diva Maria Malibran, Donizetti’s first Maria Stuarda and Chopin’s “queen of Europe,” who died after a fall from a horse in 1836.

Viardot herself was perhaps the most fêted opera singer of the 1840s and 1850s. She conquered London, Paris, and St. Petersburg with performances of operas by Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti in which she was noted for the naturalness of her acting and the purity of her singing. “No one,” wrote the poet Théophile Gautier of the outset of her career, “could forget her adorable gaucherie and naiveté worthy of the frescoes of Giotto.” George Sand hailed her as a “priestess of the ideal in music” and became her “maternal and dearest friend.” Viardot was immortalized in print as the model for the adventurous heroine of Sand’s novel Consuelo (1842–1843), which celebrated the writer’s ideals of female autonomy and independence.

At the same time, a certain exoticism was always a crucial ingredient of Pauline’s renown. Heinrich Heine tried to explain:

Her ugliness is of a kind that is noble and, if I might almost say beautiful…not so much the civilized beauty and tame grace of our European homeland, as the terrible splendour of an exotic wilderness.

For Alfred de Musset her voice had about it something of the taste of wild fruit. Camille Saint-Saëns spoke of its having the quality of bitter oranges. Spanishness was part of her glamour, part of the Garcia brand, but intense musical training and devout seriousness of purpose were not at odds with this. Pauline originally intended to become a pianist. She took lessons with Liszt and remained an accomplished player for much of her long life. She studied composition with an associate of Beethoven’s, Anton Reicha, who also taught Berlioz and Liszt, and she composed several operas and dozens of songs. Her experience as a singing actress was intense and obsessional: “Even at night in my sleep my private theatre pursues me,” she wrote to her conductor-confidant Julius Rietz, “it becomes unbearable at times.”

The quality that allowed Pauline to triumph in what had often been a rackety profession, while remaining, even after her retirement from the operatic stage, the center of a glittering network of social and cultural contacts, was her respectability. This was something that strangely, given her own life, Sand understood, and it was Sand who rescued her from the unreliable clutches of the poet Alfred de Musset and found the eighteen-year-old a solid and supportive husband more than twenty years her senior: the opera impresario and Hispanophile Louis Viardot. It was Louis, trained as a lawyer and later an influential art critic, whose sage counsel had some years earlier rescued Pauline’s sister, Maria Malibran, from the possibly scandalous consequences of an extramarital pregnancy. For Pauline he was the guarantor of a settled life, her manager, dear friend, traveling companion, and confidant, the constant factor that anchored her career, even after he had moved away from direct involvement in opera management.

But theirs was never a passionate relationship, on her side at least. She was “unable to return his deep and ardent love, despite the best will in the world,” she wrote to Rietz. Sand spoke of Pauline’s loving Louis “only in a certain way, tenderly, chastely, generously, greatly without storms, without intoxication, without suffering, without passion in a word.” His only fault as far as Pauline was concerned—writing again to Rietz in 1858, eighteen years into the marriage—was that he lacked “the childlike element, the impressionable mood.” She found those qualities elsewhere.

In October 1843 Louis and Pauline traveled to St. Petersburg, where she triumphed in Rossini’s Barbiere and Otello, Bellini’s La Sonnambula, and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. That November Louis met a young man named Ivan Turgenev—“a young Russian landowner, a good shot, an agreeable conversationalist, and a bad poet,” as he was introduced. It was Turgenev’s twenty-fifth birthday. A few days later, already a keen fan of Pauline and something of a groupie—he had annoyed other audience members by the ferocity of his applause—Turgenev was introduced to her. Before long, he was joining her in a private room after performances, along with three other ardent admirers. They brought her in tribute a pure piece of fierce Russian exoticism: the skin of a bear they had shot. Pauline had it made into a rug with golden claws. In a scene atmospherically reminiscent of Turgenev’s masterly novella First Love, in which Zinaida teases and torments her hangers-on, playing forfeits for kisses, Pauline would loll on the rug after her performances while Turgenev and his friends/competitors were each given a corner to sit on. They became known as “the four paws.”

Advertisement

As so often with Turgenev, scenes like this from his life would be reprocessed in his fiction—those cruelly flirtatious games in “First Love,” or the relationship with a ballet dancer recounted in the epistolary short story “A Correspondence”: “From that fatal moment I belonged to her like a dog…. I never anticipated that I should come to hanging about rehearsals.” Initially Pauline was not particularly interested in the young Russian giant, six foot three, with his high-pitched voice, short legs, lorgnette, and fashionable lisp. The Russian writer Alexander Herzen early on remarked on Turgenev’s foppishness, his cleverness, his superficiality, and his “boundless fatuity.” That fatuity, high-spiritedness, and willingness to abandon himself to sheer silliness were surely what appealed to Pauline, in comparison to her husband. It was a trait that Turgenev maintained throughout his long association with the Viardot family. In his sixties he was still up for impersonating a chicken or performing an impromptu silly dance. Sourfaced Tolstoy, on a long visit, made a laconically crushing note in his diary: “Turgenev. Cancan—sad. Meeting peasants on the road was joyful.”

What is clear is that when Turgenev met the Viardots, Pauline was a somebody and he was, essentially, a nobody. In the formation of their renowned ménage à trois—perhaps the most famous in artistic history, of long duration and unique cultural significance—which stands at the center of Orlando Figes’s latest book, The Europeans: Three Lives and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Culture, it was Turgenev’s friendship with Louis that was surely the crucial determining factor, and not just because of Louis’s calm complaisance (“your husband would let you do whatever you wanted,” Sand once wrote to Pauline).

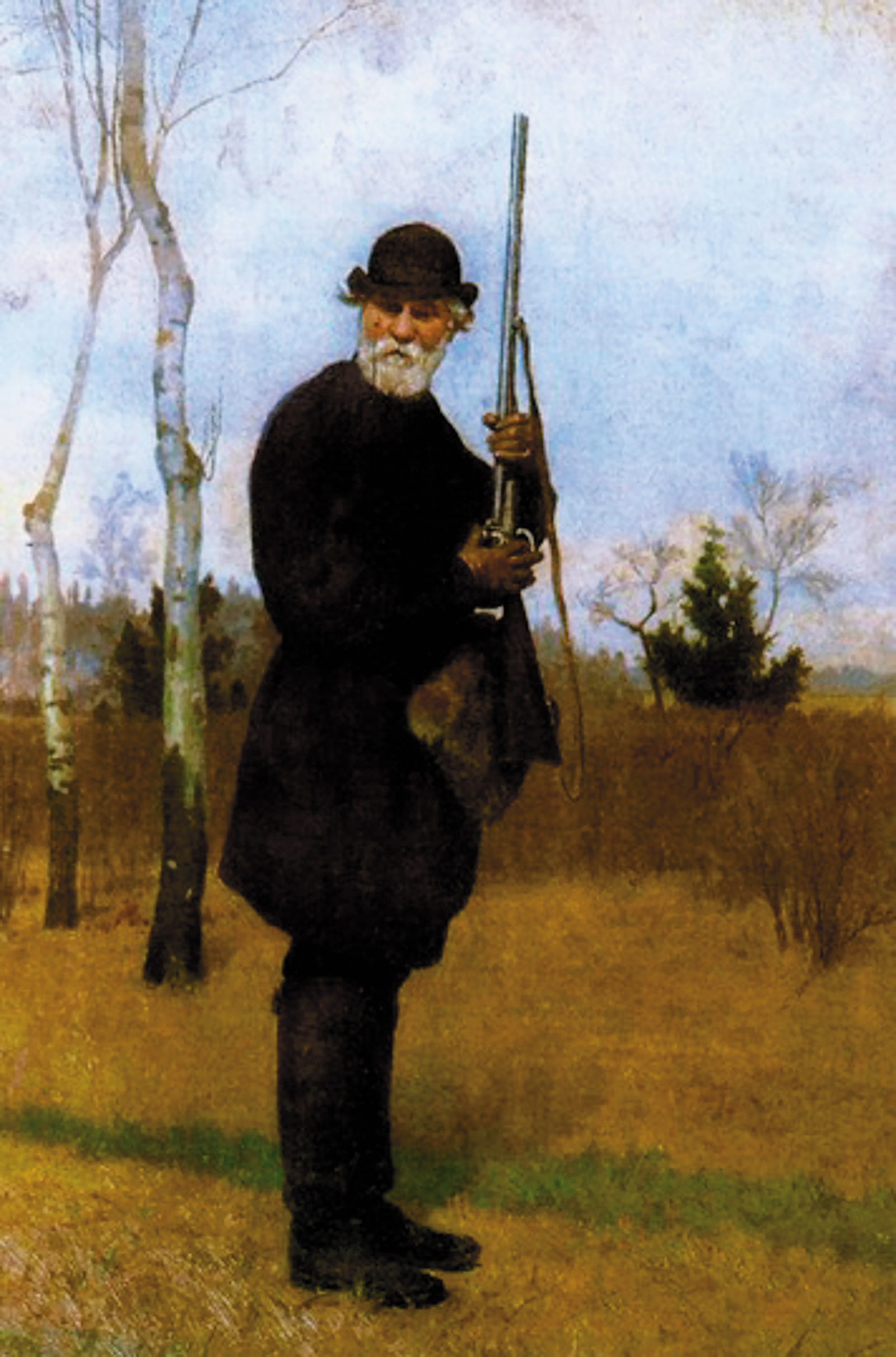

That anecdote of the bear rug encapsulates the importance of shooting wild animals throughout most of Turgenev’s long association with the Viardots. The first time he met Louis in St. Petersburg, he invited him on a hunting trip the following day; their earliest conversations were about hunting and literature. In 1844 Louis published in the French journal L’Illustration an account of his hunting parties in Russia with a young nobleman. After a second visit to Russia, the Viardots returned to Paris in 1845 with Turgenev in tow; he spent the summer with them at Courtavenal, their country house southeast of Paris. This was the “happiest time of my life,” he later wrote, a summer in which his intimacy with Pauline intensified and he felt his love for her being reciprocated. The following year Louis published his Souvenirs de Chasse, a book popular enough to go into its fifth edition in 1852, the same year that Turgenev published the collection of short stories, Sketches from a Hunter’s Album, that made his name.

Louis Viardot’s hunting memoirs do not have a great deal in common with Turgenev’s first masterpiece, which is as much about peasant life as about hunting, but the two books were clearly bound up with each other, and it was not for nothing that Turgenev described Courtavenal as the “cradle of my literary fame.” The Sketches—full of lively and unsentimental character portraits, and suffused with Turgenev’s alchemical capacity to combine the photograph and the poem, well noted by Virginia Woolf—turned him into a literary lion.

But it also created an enormous and unforgettable political stir in Russia, with a governing class nervous about Turgenev’s depiction of the realities of serf life, its squalor and its humanity: Turgenev was detained for a month and spent eighteen months under house arrest. Abraham Lincoln’s supposed quip on meeting Harriet Beecher Stowe—“So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!”—captured something of the importance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in creating the preconditions for emancipation in the United States. The Sketches, published the same year as Stowe’s novel, had a similar impact on the Russian debate about serfdom, which led to its abolition in 1861. When Turgenev’s body was returned for burial in Russia some twenty years later, crowds turned out at every railway station stop on its European route; in St. Petersburg, despite official disapproval and a heavy police presence, about 400,000 people lined the route to the cemetery. Turgenev was the writer who had given the Russian peasantry a human face.

Advertisement

Turgenev went on to live with the Viardots at Courtavenal, in Paris, in London, in Baden-Baden. He declared that he would even follow them to Australia if Pauline required it. There were long periods of alienation and separation, and several other entanglements for both of them (with the French composer Charles Gounod for Pauline; with the young Russian actress Maria Savina for Turgenev); but their relationship, which had started with a distant view at the opera and the charm of a particular voice, ended up with Turgenev’s living in rather cramped rooms above the Viardots in Paris. He had a bust of her and a model of her right hand in his study, which was directly above the room where she taught her singing students; he installed a speaking tube so he could hear her better.

If Courtavenal was indeed the cradle of Turgenev’s fame in a fairly straightforward sense—he composed most of the Sketches there, and the hunting country around the estate was surely a nostalgic invocation of his own Russian estate at Spasskoe—the unorthodox, “consumptive” relationship (a term he used in the play A Month in the Country) with Pauline infiltrated and inflected much if not all of his writing over the next three decades. He told Countess Tolstoy that he only started to plan work “when I have been shaken by the fever of love,” and admitted to Tolstoy’s great friend the poet Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet (Turgenev had introduced them) that he was “only happy when a woman puts her heel on my neck and grinds me into the dust.” His novels and stories are full of love triangles, of weak men and dominant women. Although Turgenev’s copious letters to Pauline contain much adoration and devotion, and while much of the time he spent with Pauline and Louis was companionable and domestic, the sadomasochistic aspect of the relationship that occasionally surfaced in stray remarks was at the center of much of his literary output.

It was during a long period of distance between the two that Turgenev worked hardest to produce his most substantial body of work, which included First Love and culminated in his most famous novel, Fathers and Sons. Pauline is, as the biographer Henri Troyat put it, “ever-present, even between the lines.” But it is in one of the works of his precocious old age—Turgenev at fifty seemed as old and white-haired as the sixty-eight-year-old Louis, and they died within months of each other—that he expressed most intensely the strange mixture of ecstasy and slow poison that life with Pauline had been for him.

Spring Torrents (1872) opens with the fifty-three-year-old nobleman Dimitry Pavlovich Sanin, a proxy for Turgenev, musing in his study, prey to the same dark thoughts to which the novelist himself was prone, his “classic nightmare,” as V.S. Pritchett calls it, of shapeless and monstrous sea creatures crowding the depths and eventually overcoming him. Searching among old letters for distraction, he finds a tiny garnet cross that recalls to him a luminous and romantic love affair he had at the age of twenty-three in Frankfurt with Gemma, the daughter of an Italian confectioner. The action is memorable: Sanin’s successful attempt to revive Gemma’s sick brother, which begins the affair; an excursion for a picnic; and an abortive duel. The story is full of exuberantly drawn figures: the pompous German fiancé Herr Klueber, the old family retainer and superannuated opera singer Pantaleone Cippatola. But it is the characters who precipitate the shameful end of the affair that linger in the mind, with a denouement that leaves a nasty taste in the mouth.

Looking for a buyer for his Russian estate so he can start an unlikely new life with Gemma in the confectionary business, Sanin encounters an old schoolfriend, Ippolit Sidorych Polozov, who assures him that his wife will do the deal. He has married well, to Maria Nikolaevna, a wealthy woman from the lower classes with an exotic gypsy beauty. But the marriage is a sort of sham: Polozov is a rather pathetic and implicitly impotent parody of the cavaliere servente, in his red fez and a dressing gown “of the richest satin,” dribbling orange juice from his mouth. He is relentlessly presented as effeminate, with his “puffy hands, dangling limply,” his “round, hairless chin” and “rotund thighs.” “I am a convenient husband,” he declares, “she goes her way, and—well—I go mine.” He does his wife’s hair and shops for her clothes.

But Polozov is not simply a parodic portrait of a man dominated by his wife, a nightmare version of Louis. He is also equipped with his creator’s predilection for chivalric hand-kissing and his notorious high-pitched voice, and thus an image of Turgenev himself. Is Polozov Louis Viardot? Is Sanin Ivan Turgenev? Or do these boundaries melt? Polozov draws Sanin into his orbit—they play the card game old maid together—and in an unholy wager between husband and wife, Sanin is reduced to another of the enslaved, his happiness blasted. Maria Nikolaevna wins the bet by seducing Sanin. He abandons Gemma and spends the next few years incarcerated in a punishing ménage à trois with the Polozovs, with “all the degradations and vile sufferings of a slave, who is not permitted either to be jealous or to complain, and who is discarded in the end like a worn-out garment.”

Contrary to his customary practice, Turgenev did not show this story to Pauline. If she read it, she might perhaps have seen herself more in the character of the girlish Gemma than the predatory Maria. In a sort of coda, Sanin tracks his lost love to America, where she is happily and prosperously married with five children. The story ends with another sort of ménage à trois in prospect: “They say that [Sanin] is selling all his estates and is planning to move to America.”

From his history of the Russian Revolution, A People’s Tragedy (1996), to his searing accounts of the day-to-day impact of Stalinist rule—The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin’s Russia (2007) and Just Send Me Word: A True Story of Love and Survival in the Gulag (2012)—Figes has shown an unerring ability to weave together the political and the personal. His broad-ranging Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (2002) manages to avoid the bland generalizations of synoptic history, anchoring grand narrative in specific personal stories. Natasha’s Dance is also informed by an overarching theme—the relationship between ideas of Russia and ideas of Europe—that he takes up more obliquely in The Europeans.

The Viardot-Turgenev story has been told many times before: by April FitzLyon in her superb life of Pauline, The Price of Genius (1964); by Pritchett in his haunting and delicate account of Turgenev’s life and work, The Gentle Barbarian (1977); and more recently by Barbara Kendall-Davies in an exhaustive two-volume biography of Pauline (2012). Figes tells the tale with his customary vigor and sensitivity but in counterpoint with a panoramic yet engagingly detailed survey of the creation of a pan-European culture suspended between the revolutionary moment of 1848 (for which Pauline composed an official cantata based on the “Marseillaise”) and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 (which forced the Viardots and Turgenev to leave the hitherto cosmopolitan environs of Baden-Baden). The two registers—the personal and the world-historical—intertwine and reflect back on each other.

Through Pauline we witness the creation of a new operatic world of international touring, agents, publishers, and electric stage lighting. Figes is acutely aware of the ways that material changes interacted to produce cultural change: for example, the virtuous circle between productions of operas and the reproduction of sheet music that carried their favorite melodies into bourgeois homes increasingly equipped with pianos. In 1845 Paris, a city of one million, could boast 60,000 pianos and 100,000 piano players. As opera companies toured and audiences traveled greater distances to attend performances, the recycling of musical material by composers, which had been common in eighteenth-century musical life, became unsustainable, and a canon began to crystallize.

Louis, collector and influential critic, writer of widely disseminated guidebooks, gives us a window onto the art market, the development of the art book, and the birth of modern European cultural tourism. Between 1852 and 1855 Hachette published five of his guides to European museums in their pocket travel editions. Covering France, Italy, Spain, Germany, and England/Belgium/Holland/Russia, they sold tens of thousands of copies. It was partly under his influence that art museums started hanging pictures by national school and period. The second English edition of Louis’s Les Merveilles de la Peinture (1877) was an early instance of the use of photographic reproductions.

Turgenev was a living embodiment of the cosmopolitanism whose creation Figes is celebrating. “I am a European,” he declared, “and I love Europe; I pin my faith to its banner, which I have carried since my youth.” Through Turgenev, we are present at the birth of a truly European literature, symbolized by his friendships with colleagues such as Émile Zola, Gustave Flaubert, and Henry James. But that epoch of literary Europeanization was brought into being by new capitalist systems of publishing and printing, and the crucial influence of shifting copyright regulation, in which Turgenev himself was closely involved. He was also constantly engaged in encouraging the translation of Russian literature into other European languages and vice versa. It is an irony that Russia’s eventual failure to ratify the Berne Convention of 1886 left Russian works unprotected by copyright and allowed the flooding of the market with translations in the late nineteenth century. Thus was the Russian soul transmitted into the Western marketplace.

The Turgenev-Viardot triangle is less the focus of The Europeans than is the trio of technologies that transformed their world and created this new cosmopolitan culture: lithographic printing, photography, and the railway. It was lithography that allowed the dissemination of cheap mass editions of literary classics, new popular fiction, and sheet music. It also transformed notions of the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, as countless identical graphic versions of unique works of genius were distributed throughout the continent. Photography had almost as profound an impact on concepts of realism in literature as on the visual arts.

But it is the revolutionary force of the railway that runs most powerfully through Figes’s accelerating saga. Dickens—no slouch at restless nonstop travel—compared the Viardot household to a railway junction where people were changing trains. Turgenev spoke of his “nomadic Tatar blood,” but his particular species of nomadism was enabled by the increasing speed and elaboration of the European rail network. In the 1850s it took him three weeks to reach Paris from his estate at Spasskoe; in the 1870s, five days. If, as Figes writes, the Viardots and Turgenev were “influential figures with an international reach” who “through their international connections…help[ed] to advance the cultural integration of the Continent,” the railways made that possible, both for their traveling arrangements—whether as a singer on tour or a cultural emissary—and for all the things that the railways did, both highly concrete and more abstract, to create a pan-European public sphere. Letters were delivered more quickly, newspapers reached out from the metropolis, distribution costs of books plummeted.

Heine was one of the first to express the metaphysical and vertiginous sensation that the internationalization of rail travel provoked. “Space” he wrote, anticipating Karl Marx, “is killed by the railways, and we are left with time alone.” At the opening of the Paris-to-Brussels line in 1846, Baron James de Rothschild of the Chemins de Fer du Nord gave a speech in which he said that railways would bring Europe’s nations together. As Constantin Pecqueur, a follower of Saint-Simon, put it in 1839, “To foreshorten for everyone the distances that separate localities from each other is to equally diminish the distances that separate men from one another.”

Yet if railways could stimulate the elaboration of a common European culture, many of whose constituent parts we still enjoy today, they were not only a force for openness. Culturally, the reaction against the speed and promiscuousness of modern life set in early. We see it in the midcentury cult of the flâneur, the cultivated stroller who stands back from the frenetic crowd and observes. When the German novelist Theodor Fontane declared in 1843 that “Romanticism is finished on this earth, the age of the railway has dawned,” he could not have known that the response to the new industrial age would be the turbocharged late Romanticism whose patron saint was the arch-nationalist Richard Wagner. Railways created international links, but they also built nations and increasingly formed part of the arsenal of modern warfare in the age of nationalism that succeeded the Franco-Prussian War. Railway timetables made possible the new international tourism, but they also accelerated conflict between nations. In the age of the Internet we know all too well that vaunted technologies of openness can quite easily cut the other way.