There’s a funny sequence halfway through Nell Zink’s second novel, Mislaid, in which one of the main characters, a frustrated playwright, tries without much luck to get her career off the ground. “She subscribed to Writer’s Market and queried five agents about her play The Wicked Lord,” Zink writes:

They all said the most interesting character dies too near the start. She reacted by writing a play in two days and a night about a utopian lesbian commune defending itself from real estate interests. The villain saved his appearance for the end. The lesbians became the bacchants of Euripides, killing him in a festive manner.

It was gripping and seemed to write itself. But she knew you can’t publish material like that.

The joke, or one of the jokes, is that Zink does publish material like that—her next novel, Nicotine, was about a utopian (smokers’) commune battling its churlish landlords. She also has a habit of killing off interesting characters sooner than seems wise, though the cheerful revenge of the bacchantes in her books rarely takes the form of physical violence. Her novels, famously written quickly (three weeks is usually cited as the time it took to draft each of her first three books), do, at times, read as though they wrote themselves; their startling combinations of registers and breakneck plots sometimes give the impression that they sprang directly from the author’s unconscious, if a more rigorously structured one than that of, say, the Beats. Though Dickens is often invoked as a point of comparison for writers of wildly varying styles and quality, Zink may be the contemporary writer who most deserves the comparison. She has a Dickensian gift for caricature and set pieces, as well as his nagging, theatrical tendency to wrap all the story’s loose ends in a bow. There are hints of early Penelope Fitzgerald in her embrace of misfits (as well as in her late start to publishing), and a healthy dose of the English novelist Barbara Trapido, whose Brother of the More Famous Jack shares Zink’s zest for bad literary manners.

But she is, for the most part, startlingly original. The five books that Zink has published since 2014 are defined by a fervent restlessness, a desire to ignore the strictures that usually confine the contemporary novel. Her books, and her characters, are impolite about sex, race, gender, and class in ways that are often thrilling, and occasionally tiresome. Viewed from a distance, her novels, based on their subject matter alone, each seem to be “about” one or more significant contemporary topics: her first novel, The Wallcreeper, is a picaresque about environmental activism; Mislaid’s plot revolves around a white lesbian passing as black in Virginia in order to elude her gay husband; and her latest novel, Doxology, follows a New York couple from the late 1980s through the 2016 election, with the events of September 11, 2001, serving as a pivot in the novel and in the characters’ lives. But Zink doesn’t really write topical novels. Rather, she uses these charged subjects as springboards for her deadpan riffs, running roughshod over the idea that serious subjects need be addressed with anything approaching solemnity.

The story of Zink’s long apprenticeship and entrance into the literary world is so good that, for a few years, it threatened to overshadow her actual writing. She was born in California in 1964 but grew up in Virginia, in rural King George County, an area with a significant black population and, as she recalled in a 2015 New Yorker profile by Kathryn Schulz, a disproportionate number of Klan members. Like many of her characters, she had an unhappy childhood and adolescence, and after studying philosophy at William and Mary, she fled from the expectations of a bourgeois life. For a brief period in the mid-1980s, she became “intentionally homeless,” then worked for four years as a bricklayer in the Tidewater region of Virginia. She got married, moved to Hoboken, and in the early 1990s produced a zine “about harsh lo-fi indie rock, combined with cute animals.”

In 1995, Zink and her husband moved to Philadelphia, and split up almost immediately. In 1996, however, an article in the Inquirer about Zink’s zine inspired a visiting Israeli poet to write to her in admiration. Within a year, she’d married him and moved to Israel.

There, she struck up an intense friendship with the writer Avner Shats, and though she spoke little Hebrew, she attempted to read his novel Sailing Toward the Sunset. She gave up and wrote her own novel, entitled Sailing Towards the Sunset by Avner Shats, in a series of emails to him in December 1998. (The novel, published in 2016 in the volume Private Novelist along with another novella she wrote for Shats, is a Tristram Shandy–inflected series of digressions, filled with pithy commentaries on various books and authors, flights of fantastical literary invention, and occasional stabs at translation from the Hebrew.)

Advertisement

In 2000 she moved to Germany, where her rendezvous with literary destiny came in the form of a letter she sent to Jonathan Franzen in early 2011, responding to one of his articles about birds in The New Yorker. He was drawn in by her antic and erudite voice on the page, and over the course of a voluminous correspondence, encouraged her to write fiction for a broader audience. She responded by writing the first fifty pages of The Wallcreeper in, if you believe the legend, four days. (Beyond the shared interest in birdwatching and environmentalism, the published novel also includes a direct hat tip to her pen pal’s literary enthusiasms in a throwaway line of dialogue about “a book some guy raved about in the Times called The Man Who Loved Children.”) After taking a break to work on a translation project, she spent another couple of weeks finishing the novel and sold it to Dorothy, an excellent small press dedicated to publishing books by women.

The Wallcreeper begins with a sentence of such chutzpah and precision—“I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage”—that it is the rare reader who encounters it and does not continue on. An opening like that could, in other hands, betoken a kitchen-sink realist novel about a couple’s loss and recovery, or a spare, Didionesque glimpse into the existential void. But in Zink’s hands, it’s the prelude to something much shaggier and weirder, with a pace and density that is unique to her body of work.

In the first twenty-five pages alone, Tiffany, the narrator, briefly but convincingly mourns the sudden end of her pregnancy, helps her husband nurse back to health the injured bird that caused the car accident (her husband has named it Rudolf, after Rudolf Hess, because its colors remind him of the Nazi flag), and embarks on an affair with a Montenegrin gas station employee named Elvis. Stephen and Tiffany live fifteen minutes from downtown Bern, Switzerland, a city where everything “had a delicious texture advertising a rich interior. Nothing was façade. It was clean all the way down forever and forever, like the earth in Whitman’s ‘This Compost.’” The writing is a sui generis pileup of sexual frankness, literary and historical allusions, and aphoristic punchlines, as in:

He knelt across my chest and eventually sort of fucked my mouth. He was uninhibited, as in inconsiderate. I felt like the Empress Theodora. Can I get more orifices? I thought. Is that what she meant in the Historia Arcana—not that three isn’t enough, but that the three on offer aren’t enough to sustain a marriage?

Of Elvis, she writes, approvingly, “Objectifying my body saved him from objectifying my mind.” The reader, if the reader is into this kind of thing, has likely objectified Zink’s mind, or at least her prose style. The book loses steam after its delirious opening stretch of European club-hopping and spouse-swapping, with a plot about environmental nonprofits and eco-sabotage that, despite a great deal of rigamarole, doesn’t seem to quite sustain Zink’s attention. But that opening hook is so powerful that it remains in the mind long after the rest has faded.

If The Wallcreeper played like an underground EP that miraculously found an audience in the larger world, her 2015 novel Mislaid felt like a major label debut done right—more polished and accessible, but preserving the anarchic spirit that made her work so exciting. It is still her most fully realized novel, notable for its generosity and for its textured, knowing depiction of the South of her youth and, given her longtime residency outside the country, an impressive estimation of how it has evolved, or not. There’s a funny moment in which Cary, a gay good ol’ boy, refers to “the No South.” When he is corrected—he must mean “the New South”—he stands firm. “You can’t have ‘New’ and ‘South,’” he says.

It’s oxymoronic. I’m talking about the No South. The unstoppable force that’s putting in central air everywhere until you don’t know whether it’s day or night. Fat boys used to spend their lives in bed and only come out to fish and hunt. Now they go into politics and make our lives hell.

The novel reads at times as an affectionate tribute to the banter cooked up by the bards of the “No South,” writers such as Barry Hannah and Padgett Powell, whose combinations of avant-garde prose and regionalism share a particular kinship with Mislaid.

Cary’s interlocutor in that conversation is Lee Fleming, the star poetry professor at Stillwater, a bucolic women’s college in Virginia. When the novel opens, in the 1960s, Lee is at the height of his powers, teaching oversubscribed poetry classes and hosting legendary parties at his house across the lake from the college (“John Ashbery shooting a sleeping whitetail fawn from a distance of three yards. Howard Nemerov on mescaline putting peppermint extract in spaghetti sauce”). Lee is as openly gay as one can be in that time and place, but protected from overt bigotry by his family’s wealth and influence. Zink sets him on a collision course with Peggy, a young woman who has chosen Stillwater specifically because it is a “mecca for lesbians,” yet finds herself, to both of their surprise, seduced by Lee in his canoe: “She was androgynous like the boys he liked, but she made him wonder if he liked boys or just had been meeting the wrong kind of girl.” It turns out he still mostly likes boys.

Advertisement

Nevertheless, they embark on a torrid affair, which swiftly results in Peggy’s becoming pregnant and being kicked out of school for “fraternization.” In a characteristic blur, they get married and Peggy has two babies, whom she loves and resents in roughly the standard proportions. Then, through a series of developments that make sense, sort of, if you squint, Peggy catches Lee cheating with a boy, drives his beloved Volkswagen into the lake in revenge, and, in response to her husband’s threat of having her committed, flees into parts unknown with their daughter Mireille, leaving her son Byrdie behind with Lee. All of this serves as prelude to the audacious, pseudo-Shakespearean conceit at the heart of the novel: Peggy, to avoid discovery by Lee, purloins a copy of the birth certificate of a recently deceased black toddler, giving her name, Karen Brown, to Mireille and rechristening herself Meg. They will, she decides, despite her daughter’s pale skin and blond hair, pass for black in rural Virginia.

Peggy, and Zink, somehow, mostly, get away with it. The joke, of course, is that Peggy and Mireille are using the arbitrary and racist “one drop” rule to their advantage; by declaring themselves black, a categorization that is accepted without question by everyone they encounter, they’re immediately shunted into a different social stratum, one that renders them invisible to their white pursuers. Though Zink can be glib—occasionally her caricatures tiptoe up to the line of stereotype, and there is sometimes a glint of nastiness lurking beneath the silliness—her fundamental decency tends to keep her from getting into too much trouble. The second half of the novel focuses on the next generation, following “Karen” and her friendship and eventual romantic relationship with Temple Moody, a brilliant (actually) black neighbor who proves to be the book’s moral compass. The story gets a bit bogged down in zany mistaken identity shenanigans—both Byrdie and Karen end up at UVA, get caught up in a byzantine legal situation involving a fraternity and drug possession, and take an excruciatingly long time to discover that they’re brother and sister—but Zink’s mordant prose and humor just about keep things on track.

Nicotine, the follow-up to Mislaid, bears signs of being rushed and undercooked. Zink was refreshingly honest about the mercenary origins of the book, explaining to an interviewer that it was drafted and sold in the period between the New Yorker profile and the publication of Mislaid, in order to secure the largest advance possible. However, since this doesn’t seem much different from the method of composition of her earlier books, the more telling comment she made about the book’s gestation was that its present-tense narration and rambling one-thing-after-another plot were inspired by both television shows and young adult fiction, influences too pernicious, apparently, to entirely overcome.

Even as it shares many surface qualities with Mislaid—in place of the earlier novel’s Peggy, a heroine named Penny—the ingredients never set. The book’s speed feels reckless as opposed to deliberate. There’s an early scene in which Penny, age twelve, interrupts her half-brother having sex with his girlfriend, tussles awkwardly with him, then tells her father that he tried to rape her, at which point her father gives her a warm, Atticus Finch–like talking-to about not making false rape accusations. The tone is so jarring that the novel never recovers.

Though the book is ostensibly about Penny’s escapades with a group of squatters who have occupied her now-deceased father’s childhood home in Jersey City, there’s an underlying violence, often connected to sex, running through it that the plot can’t quite accommodate. Everyone in the book wants to, and often does, have sex with everyone else—Penny’s mother, Amalia, we learn, was Penny’s father’s adopted daughter, whom he had originally found wandering around a garbage dump in Cartagena, before she became his wife. Amalia is desperately in love with Matt, her former adoptive brother, now stepson. Matt, a sociopathic yuppie, develops a sexual obsession with Penny’s nymphomaniac housemate Jazz, into whose bed Penny also falls. Penny is desperate to have sex with her housemate Rob, but he identifies as asexual. (It turns out he’s just self-conscious about the size of his penis; he’s cured of this by also having sex with Jazz.)

The book is crude and messy, impossible to take entirely seriously. But there’s also real pain being expressed, something beyond the novel’s borders. Its defining scene might be a singularly disturbing one in which Matt and Jazz have sex while hooked up to a virtual reality device that renders Matt as a terrifying monster, an encounter Jazz finds so nightmarish she tries to throw herself off the balcony of his apartment, only to be pulled back from the edge for more sex. It’s awful, but it’s certainly memorable.

After the chaos of Nicotine, I didn’t know what to expect from Doxology. The events and aftermath of September 11 and the 2016 presidential race did not seem a natural fit for the Zink treatment, perhaps because the world’s insanity has outpaced even the imagination of an expert hyperbolist. Though there are a few of Zink’s trademark moves—notably a couple of side characters who run away with large portions of the plot—her approach to the broader canvas has changed. The characters, especially the central couple, grow and develop in more subtle ways over the course of the novel than Zink’s characters usually do, and the story proceeds at a more measured pace than any of her previous books. It shows signs of a longing, not entirely fulfilled, to meet the world where it is.

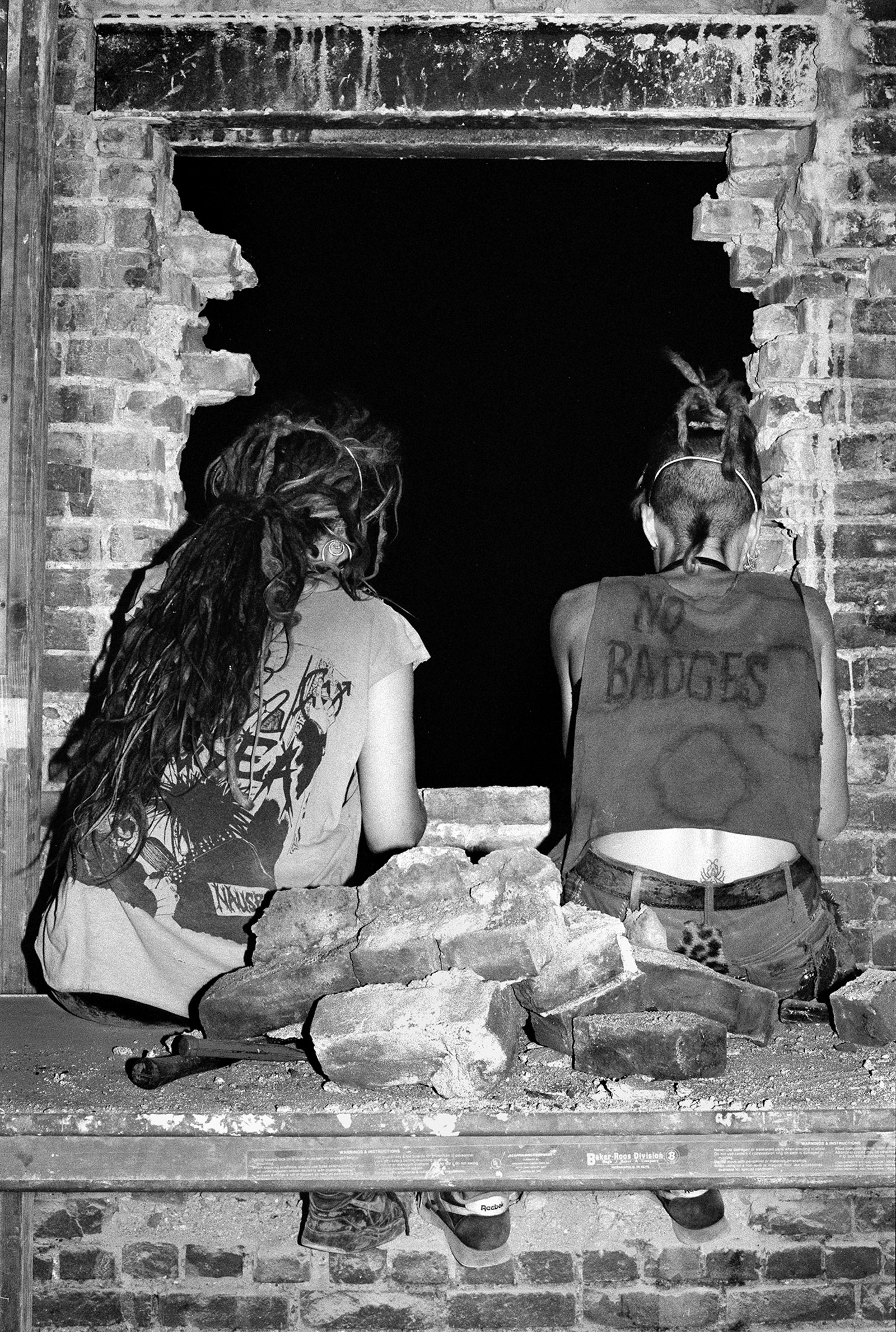

The first half of the novel follows the rise of a singer named Joe Harris, who becomes an unexpected Nineties alternative rock star, and his friendship with a bohemian couple, Pam and Daniel, living on the Lower East Side. It’s an affectionate portrait of an independent music scene that has long since vanished, one in which newly formed bands who could barely play their instruments performed at audition night at CBGB’s and diehard music nerds debated the very existence of a Sonic Youth single, supposedly distributed to subscribers of the zine Forced Exposure, called “I Killed [Robert] Christgau with My Big Fucking Dick.” For readers with any investment in that heady period, this section of the novel is a trove of references and allusions, and surely the best fiction written so far about the competing priorities and improbable successes of that time.

Joe, we are told in the novel’s opening sentence, is a “case of high-functioning Williams syndrome,” a genetic condition whose typical features include a “broad mouth, stellate irises, spatial ineptitude, gregarious extroversion, storytelling habit, heart defect, and musical gift,” though, crucially, he lacks the “general intellectual disability that was the syndrome’s defining feature.” This character introduction via list of clinical symptoms reads as a deliberate thumb in the eye to the conventional notion of “show don’t tell” in fiction, a gesture something like the chapter titles in eighteenth-century novels that tell you what’s going to happen next.

Joe’s childlike nature, compulsive musical productivity, and unlikely brush with mainstream success bear some parallels to the life and career of the Austin-based songwriter Daniel Johnston, who, despite severe schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, created a moving and brilliant body of work. (Johnston died at age fifty-eight last September.) The layers of referentiality in the Joe Harris narrative are dense if one cares to indulge them—Harris has a heroin-junkie girlfriend who attempts to cash in on his fame, clearly a play on the saga of Courtney Love and Kurt Cobain; Cobain was Daniel Johnston’s most famous fan, almost single-handedly landing him a major record deal at the peak of Nirvana’s popularity by wearing a shirt featuring his album art on MTV. It’s also hard, for those of the right age and musical taste, not to read Joe’s friends Pam and Daniel, downtown-dwelling hipsters who collaborate on musical projects, as a low-key riff on Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon, the married couple who served as the core members of Sonic Youth until their separation in 2011.

These things are fun to track, but more important than catching the specific allusions is the sense that Zink knows this world intimately. The early pages of the book, in which she sketches Joe’s and Pam’s separate journeys through adolescent attempts at art-making and self-expression, perfectly capture the giddy rush of identity formation. As a teenager, Joe plays along to songs on the radio, then starts writing his own when he runs out of new songs he likes:

He sang his favorites in public, with hand motions, louder than he could really sing, his voice ringing and rasping, the sound effortful, conveying obstacles overcome, the drama of stardom, the artist as agonist, in part as a side effect of singing outdoors against ambient racket and traffic.

Pam, meanwhile, grows up in a WASP family in Washington, D.C., against which she begins to rebel as soon as she figures out how. Like many a wayward youth, she finds a home in the hardcore punk community—specifically, despite her precocious interest in drugs and boys, in the abstemious straight-edge scene defined by Minor Threat in the early 1980s. (“She was well-read enough to know that a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”) At the beginning of her senior year of high school, she pawns her father’s audio receiver and VCR for bus money and runs away to New York. She quickly joins a terrible band and finds a job as a programmer for a nascent computer consulting firm run by Yuval Perez, “a draft evader who had turned eighteen just before Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon.” (One of Zink’s mostly endearing tics is that everyone gets a backstory, even if it is sometimes of the “picnic, lightning” variety.)

Through her friendship with Joe (which begins, inauspiciously, with Joe exclaiming, “You’re great-looking, except for your hair!” while waiting in line behind her for coffee), Pam meets and falls in love with Daniel, who occasions one of Zink’s most inspired arias, in which she explains “the eighties hipster” and his crucial differences from both the earlier Fifties model and the “bearded and effeminate cottage industrialist who came to prominence as the ‘hipster’ in the new century.” The Eighties hipster, Zink explains,

was a by-product of the brief, shining moment in American history when the working class went to liberal arts college for free….

An eighties hipster couldn’t gentrify a neighborhood…. All he wanted was to avoid retiring from the same plant as his dad….

The mod, the glam rocker, the rockabilly, the punk, even the prep risked and defied the wrath of the homophobe, but the eighties hipster could get served a beer in the Ozarks.

Is this true? It’s certainly funny, and it captures the hard-edged form of nostalgia that Zink more or less has a monopoly on. Daniel, befitting his station as defined by Zink, lives in an illegal apartment accessible only by passing through an odds-and-ends store on the edge of Chinatown. (If he comes home after the shop closes at 1 AM he has to wait until morning to get into his apartment.) The rent is $100 a week. Improbably (except maybe to long-time New Yorkers), he, and then Pam, and then their daughter, live in this firetrap for the next thirty years. The rent eventually goes up, but not too much.

Though more deliberate than her previous books, the novel still keeps up an impressive pace, charging headlong through the decades. Daniel, Pam, and Joe briefly form a band, but Joe turns out to be the only one with star potential, and his ascent powers the narrative. It seems absurd at first that Joe has an MTV hit in the 1990s with a song called “Chugalug,” which mostly consists of him repeating variations on “I rub my nub” over “a big-beat synth percussion track,” but then you remember that the era produced stoner classics like “Natural One” by Folk Implosion, “Peaches” by the Presidents of the United States of America, and, granddaddy of them all, “Loser” by Beck. Zink is sharp on the way that the gawky-looking, irritatingly hyperactive Joe transforms into a pop idol through the magic of the show business machine. On screen,

his Muppet mouth became a twenty-tooth smile. His small head became enormous eyes; his girlish chin, an asset at last…. It was like some strange proof of the existence of a parallel universe looming behind our own.

Joe grows famous but doesn’t lose his innocence; he’s a regular babysitter for Pam and Daniel’s daughter, Flora (“being a rock star was not a day job”), taking her on long walks through Manhattan, during which he “queried psychotics about their sores and frozen dessert vendors about their flavors in the same tone of disinterested fascination.” He does, however, attract bad influences, most notably Gwen, the grasping drug addict and sometime model who becomes his girlfriend. On September 11, Joe is at Gwen’s apartment on West 54th Street soon after the towers fall. She decides to “combat the stress” of the day’s tragedy by injecting heroin, and manages to talk Joe into trying it for the first time. He is injected by a drug dealer and goes into cardiac arrest. Gwen does not know CPR, and the cell phone networks in the city and all of the emergency services numbers are jammed due to the world historical events taking place downtown. Plus, she’s on heroin. Joe dies.

There is something admirably counterintuitive about having the novel’s September 11 casualty be the result of a heroin overdose in Midtown rather than the attacks. It also feels like something of a copout, although it’s too genuinely sad to be exploitative. More problematically, the loss of Joe, which occurs less than halfway through the four-hundred-page novel, deprives it of much of its narrative energy. Joe provides the perfect counterbalance to Zink’s wised-up tendencies. Without him, her gimlet eye starts to seem more cynical. Her setups are often richer and more inhabited than the follow-throughs, with promising plotlines receding from view in favor of an old-fashioned insistence on pairing characters off into romantic relationships before the book ends. Like Helen DeWitt, perhaps the contemporary closest to her stylistically, she has a weakness for a Rube Goldberg approach to plot, in which the story can’t end until every object that has been set in motion comes to rest in its predetermined place. As a result, the books can feel somewhat weightless, even after they’ve engaged with the weightiest subjects.

Much of the second half of the book is taken up with the travails of Flora as she moves into young adulthood and tries to make her mark on the world. She is, on the whole, less psychologically developed and engaging than the characters of the previous generation. After an ill-fated trip to Ethiopia to combat soil erosion, Flora becomes involved in the Green Party and starts sleeping with an older, bullish Democratic consultant named…Bull. Their relationship plays like a less violent, more conventional version of Jazz and Matt’s relationship in Nicotine, but the underlying dynamic is the same. In both cases, women with strong political and ethical stances are helplessly attracted to the raw sexual power (and financial status) of rich, older men, forcing them to reckon with the disagreements between their principles and their libidos.

While campaigning for Jill Stein in Pennsylvania (another misjudgment, to put it mildly), Flora falls into an intense rapport with Aaron, a man much closer to her age and social status who is volunteering for Hillary Clinton’s campaign. They decide to play hooky from canvassing and have sex, which results, we learn later, in Flora’s becoming pregnant. Here, in the last stretch of the novel, the overlap with recent history—and Zink’s lackadaisical engagement with it—becomes especially frustrating.

As the country grapples with a looming Trump presidency and begins to assign blame—with Clinton’s and Stein’s campaigns both coming in for a significant share of it—the novel’s focus shifts to the marriage plot. Will Flora choose to stay with Bull, who can provide stability and support, or Aaron, who, though he fulfills Zink’s deeply unimpressed description of contemporary hipsterdom, seems to provide at least an outside chance of being soul-mate material? Or neither? It’s hard to feel invested in the choice between these two, as, in the background of the novel, the world burns. It feels as though Zink is falling back on narrative convention to avoid fully reckoning with the unruly real events she’s chosen to take up. A late episode involving a rumored cloud of nuclear fallout (or is it?) over Washington raises the possibility of a provocative turn toward alternative history (not to mention toward the mid-career stylings of Don DeLillo), but Zink decides not to take that narrative exit ramp either.

The result is a book that doesn’t quite justify its deployment of the trappings of the “novel of our times.” Caught somewhere between satirizing that genre and earnestly attempting it, Zink lands in an uncertain middle ground. It may be the case that her strengths as a writer are fundamentally those of the disrupter and the caricaturist rather than the nuanced social chronicler, but the madness of the current moment calls as much for disruption as it does for breadth and grace. Doxology may prove to be a transitional book in her career, like, say, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, the work of a committed spitballer creeping toward a more sober reckoning with the world, then bailing out when things get too real.

One can perhaps best see Zink’s evolution by looking at a pair of similar scenes in Mislaid and Doxology, both of which center on a prodigal daughter’s reunion with her parents after many years. At the end of Mislaid, Peggy goes to see her long-estranged parents and finds them “unchanged,” with her mother “still putting peonies and irises in exactly the same places…. Her dad had no new hobbies or opinions. Between them lay an unbridgeable emotional gulf.” Peggy moves on quickly. In Doxology, Flora’s childhood awakens a desire in Pam to reconnect with her parents, from whom she ran away as a teenager. In this version of the reunion, her parents have transformed. “Did you really expect losing a daughter not to change me?” her mother says.

The speech she delivers is so deeply what every rebellious child wants to hear—“I got to know my boundaries a little better and acknowledged that it was all me. You were my vicarious vessel…. The world you came into didn’t inspire you to be what I wanted for myself”—that it borders on the fantastical. But it’s also moving. “Her face hadn’t changed, at least not the important parts,” Zink writes of Pam’s mother. “Her eyes were the single most familiar and persuasive thing Pam had ever known.” For a writer with such an appetite for destruction, the movement toward reconciliation and the allowance of genuine feeling requires courage. It’s heartening to see her face the danger head on.