Among the previously uncollected pieces in Donald Barthelme’s Sixty Stories is a six-pager called “How I Write My Songs.” The “I,” like many of Barthelme’s narrators, is initially anonymous; we learn his name—it turns out to be Bill B. White—only in the second-to-last sentence. The songs he writes, or that Barthelme has written for him, are country- and blues-inflected numbers, vacuous yet weirdly plausible:

Goin’ to get to-geth-er

Goin’ to get to-geth-er

If the good Lord’s willin’ and

the creek don’t rise.

White is evidently a master of his craft: “When ‘Last Night’ was first recorded, the engineer said ‘That’s a keeper’ on the first take and it was subsequently covered by sixteen artists including Walls.” Such reminiscences alternate with helpful hints, all of them comically banal: “Various artists have their own unique ways of doing a song.” “It is also possible to give a song a funny or humorous ‘twist.’” In the final paragraph the lecture modulates into a pep talk (“The main thing is to persevere and to believe in yourself”) before ending on an oddly defiant note: “I will continue to write my songs, for the nation as a whole and for the world.”

The story reads like a parody of something we half-recognize but cannot quite put our finger on. Is it the emptiness of popular song lyrics? The vapid idiom of Parade magazine? Or is it, we might wonder uneasily, Barthelme’s own readers who are being gently mocked? For the story purports to answer that question asked innumerable times of every famous artist—“Where do you get your ideas?”—with its implicit corollary: How can I do it?

Whatever else Barthelme’s story may be, it is a sly rewriting of one of the classics of American literary criticism, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Philosophy of Composition.” In that essay Poe, in his best professorial voice, explains how he went about writing his most successful poem, “The Raven.” He began, he tells us, by settling on the ideal length (a hundred lines or so), the effect to be aimed at (beauty), the tone (sadness), the central device (a refrain), the nature of the refrain (a single word), and the kind of word needed (one with prominent o and r sounds, these being “sonorous and susceptible of protracted emphasis”). “In such a search,” he adds complacently, “it would have been absolutely impossible to overlook the word ‘Nevermore.’ In fact, it was the very first which presented itself.”

But how should the refrain be introduced? At this point things take a perilous turn: “Here…immediately arose the idea of a non-reasoning creature capable of speech; and, very naturally, a parrot, in the first instance, suggested itself.” A brief vision flashes before our eyes: a nervous schoolchild standing before a prize-day audience to recite Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Parrot.” But no, disaster is averted: the parrot is weighed and considered, but ultimately discarded in favor of a raven (“equally capable of speech, and infinitely more in keeping with the intended tone”). Like his great detective, C. Auguste Dupin, Poe reconstructs logically for us the process that led ineluctably to the poem we know and love. This most emotional and romantic of poems was, it turns out, the product of cold calculation at every turn.

Or was it? Is this how anyone writes a poem? And if Poe could really reason himself into writing this smash hit, how is it that he never wrote another poem as successful? The more one reads the essay, the more one suspects that Poe’s account is a typical Poe hoax, swallowed whole by gullible readers as his circumstantial account of crossing the Atlantic in a balloon was by the New York Sun. Surely it was the poem that came first. “The Philosophy of Composition” is an elaborate piece of reverse engineering, designed to conceal from the public (and perhaps, at some level, from the author himself) the unsettling truth: that Poe had no idea how he had managed to write “The Raven,” and no idea how to write another one.

The ultimate ancestor of all such literary howdunits is Horace’s Ars Poetica. In 476 lines of dactylic hexameter, one of the great Roman poets tells us, if not how he wrote his songs, at any rate how we should go about writing ours. The advice is not all his own; an ancient commentator notes that the poet drew some of it from a third-century BC Greek critic called Neoptolemus of Parium. But it is Horace’s version that has lasted. The Ars lays down literary laws observed by writers for centuries: modern editions divide Shakespeare’s plays into five acts, for instance, because that’s how many Horace said a play should have. It canonized critical ideas, like the concept of artistic unity, that we now take as self-evident. Phrases from it have become conventional tags, some typically encountered in translation (“purple patch” from purpureus…pannus), but others familiar in the original Latin: ut pictura poesis; norma loquendi; in medias res; laudator temporis acti; sub iudice; ab ovo.

Advertisement

Yet the work is full of mysteries, starting with its very title. The rhetorician Quintilian, several generations later than Horace, evidently knew it as the Ars Poetica, but we can’t be sure that Horace called it that. The poem, now normally printed after the second book of Horace’s Epistles, is addressed to three members of the Piso family: a father and two sons. Some critics therefore prefer to call it the “Epistle to the Pisos.” But which Pisos? Piso père might be Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Julius Caesar’s father-in-law and the target of one of Cicero’s nastier invectives. Or it might be his son, consul in 15 BC. Both had literary interests, although the younger Piso is not known to have had a brother, nor can we be sure that he had two sons himself. Another candidate, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, did have two sons—but no known interest in literature. And why is the poem addressed to any Piso? Why not to Horace’s longtime friend and patron Gaius Maecenas, or to someone mentioned elsewhere in his oeuvre?

We also can’t be certain where the poem falls in Horace’s career. Many readers have wanted to make it a late work, or even Horace’s last—a poetic testament comparable to Yeats’s “Under Ben Bulben” or Stevens’s “The Planet on the Table.” A late date would fit the younger Lucius and his putative sons, and some metrical features might also support it. But there is no external evidence; if we opt for Gnaeus Piso or the senior Lucius as addressee, then the poem could be considerably earlier, a product of Horace’s prime.

That Horace should write a poem about writing poetry is not in itself surprising. But here too there are puzzles. The rest of his oeuvre falls into two parts. On the one hand, we have the Odes and Epodes, short lyric poems of great metrical virtuosity. On the other, the Satires and Epistles, loose, talky poems written, like the Ars, in dactylic hexameter. Yet the Ars itself is primarily about how to write drama, a form that Horace never practiced and which employs a meter (iambic trimeter) that he barely used. It includes side notes on epic, another non-Horatian genre.

Equally mysterious is the poem’s organization. Generations of critics have struggled to discern—and some have tried by main force to restore—a coherent structure in a text in which everything seems like a digression. Horace goes off on tangents, extends similes beyond their relevance, circles back to topics already covered. He includes a potted history of theater, not obviously useful to the aspiring dramatist, and answers elementary questions (like what an iamb is) that no likely reader could have had. As an actual manual, indeed, the Ars seems notably unhelpful. Much of its advice is negative (“Don’t put scenes that belong offstage onstage”), or uselessly vague (“Choose a subject appropriate to your strengths”), or comes down on both sides of a question (“Either take a traditional plot or invent a plausible one of your own”). A much later “Ars Poetica,” the brief poem by Archibald MacLeish, catches this quality well when it instructs us that “a poem should be palpable and mute/as a globed fruit.” It’s a lovely image, but perhaps not all that helpful to the aspiring author.

Some of the difficulty may stem from the work’s genre. The Ars is a didactic poem, a form that goes back to the beginnings of ancient literature and remained vibrant into late antiquity. The oldest surviving example is Hesiod’s Works and Days, a kind of versified farmer’s almanac. The early thinkers Parmenides and Empedocles wrote philosophical treatises in verse, and the Roman Lucretius used Latin hexameters to expound the philosophy of Epicurus. The Hellenistic Greek Nicander wrote poems about venomous snakes and cures for poisons. Aratus of Soli composed a manual of astronomy in verse, which was translated several times into Latin (once by Cicero). Later Greek poets wrote about hunting dogs and ichthyology. Ovid, predictably, wrote an Art of Love, a send-up of the whole genre, and at least started a didactic poem on cosmetology.

The didactic poet aimed both to instruct and delight—at least in theory. As Horace says in the Ars, “he hits the bull’s eye who has mingled utility with pleasure.” Of the extant poets it is perhaps Lucretius (and, ironically, Ovid) who did this most successfully. But usually utility was the junior partner. A doctor faced with a case of poisoning would have needed a scholarly commentary to understand Nicander’s Alexipharmaca, and one does not envy the aspiring farmer who tried to use the Works and Days as a real guide. This is even more true of Vergil’s Georgics, by common consent the greatest example of the form. It offers some practical information on agriculture, but in small doses—enough to give it that textbook feel, and to make digressions a welcome respite. But then, the Georgics is only ostensibly a poem about farming. Its real subject matter is what it means to be Roman, and, at a deeper level, what it means to live as a human being in a world governed by nonhuman forces.

Advertisement

“Human,” as it happens, is the opening word of the Ars Poetica. This is unlikely to be an accident. Ancient writers gave thought to beginnings; after Plato’s death, his heirs supposedly found a tablet with various versions of the opening of the Republic: “I went down yesterday to the Piraeus….” The story is probably apocryphal, yet it reveals something about the Republic, a work in which we descend from intangible verities to their pale shadows in earthly societies. The Aeneid’s first two words—“arms” and “man”—lay out its subject: “warfare and a man at war,” as Robert Fitzgerald expanded them. Simultaneously, they establish the poem’s relationship to the Iliad (a poem of arms) and the Odyssey (whose own first word is “man”).

It might seem odd, then, that the opening word of the Ars does not point more clearly to poetry—“songs,” say, or “lyre.” But it does not seem strange to Jennifer Ferriss-Hill, a classics professor at the University of Miami; her new book argues that the Ars Poetica is not really about poetry at all. It may masquerade as a guide for would-be writers, but its real concerns are larger: human behavior, family relationships, friendship, and laughter. Rather than a new departure, the poem is in her view a continuation of—or, if it is a late work, a return to—the poetry of the Satires. In those early poems, Horace explores human weaknesses and self-deception, not least his own, as they play out in social interactions. Here he does the same.

We do not typically think of literature as a branch of ethics. When W. Som-erset Maugham said that “to write simply is as difficult as to be good,” he was not equating the two. But earlier readers saw closer connections: medieval commentators categorized Ovid’s Art of Love as a work of moral philosophy. A letter of Seneca’s famously makes the case, summed up in Buffon’s aphorism, that le style c’est l’homme même. An important predecessor of Horace in this respect is the Greek Epicurean philosopher Philodemus, parts of whose treatises have been restored to us in recent years as scholars unroll and decipher charred papyrus scrolls from Herculaneum. A poet himself (he wrote epigrams), Philodemus was known personally to Vergil and perhaps to Horace too; it may not be coincidental that his principal patron was the older Lucius Calpurnius Piso. Horace mentions him by name in the Satires, and for Ferriss-Hill his “fingerprints can be discerned all over the Ars Poetica, from the passing interest evinced in anger, death, and property management to the abiding importance of friendship, teaching, and criticism.”

It is striking that the things Horace values in poetry are virtues he endorses in life as well: the importance of decorum, for example, and of knowing your place. A concept that crops up at various points in the poem is pudor, a sense of modesty or propriety, a quality as relevant to writing (for Horace) as to manners. Indeed, many terms that apply to writing can also apply to one’s character or actions. A poem, we are told, should be “uncomplicated” (simplex), but simplicity or the absence of duplicitousness is also a virtue in people.

Another example of this is rectum, a word that can mean anything between “correct, by the book” and “morally right.” Horace tells us that “most of us poets…are led astray by the illusion of correctness” (specie recti). Our writerly errors, that is, spring from a mistaken belief that we are following the rules, doing what we should. But is that not also true of many of our nonwriterly errors? Again, we are told that “the basis and wellspring of writing properly (recte) is good taste.” But “good taste” here is sapere, which can also mean “wisdom,” the quality that allows us not only to write well but to act rightly. The two words will be juxtaposed again when Horace compliments the older Piso son, who is being brought up by his father to behave properly (ad rectum) but also has good sense himself (sapis). Ferriss-Hill is attentive to such repetitions. As she notes:

Horace creates meaning by repeating specific terms, clustering them close together or layering them at intervals…often in such a way that on the second or third recurrence of a term we feel we have met it before but cannot say so for certain or recall where exactly that might have been.

If poetry in the Ars is really a stalking-horse for ethics, that might help explain something about the structure of the poem. A little over halfway through, the Ars shifts its focus noticeably, from poetry and poetic creation to the poet himself. Horace lures us in by promising to help us with our writing, but his real goal is our character and our relations with those around us. The focus on human affairs might also explain why the Ars privileges drama among other poetic forms: drama is built on human interaction and thus “provides for Horace the ideal vehicle for connecting writing with living.”

Living, and also dying. For the Ars is notably concerned with transience and mortality. Its reflections on the coining of new words and their obsolescence plainly echo Homer’s famous comparison of the generations of men to leaves. The principle that characters in drama should be portrayed in a way appropriate to their age prompts a character sketch of an irascible old man, far longer than the context seems to require, leading to a poignant meditation: “The arriving years bring many enjoyments with them/and many in their departure they take away.” The presence as addressees of two generations of Pisos allows Horace to touch on related topics: youth and age, birth and death, parents and children.

The Pisos are important to Ferriss-Hill’s reading in other respects as well. Not their exact identity, on which she is agnostic. Indeed, she suggests that it does not really matter much which Pisos are meant. Rather the aristocratic “Piso” functions in the poem primarily as a symbolic name, like “Rockefeller.” What matters is the relationship the poem itself constructs between the author and his addressees. Yet that relationship is curiously elusive. Horace shifts unpredictably from the second person plural to a singular “you” (one of the Pisos? the reader?) to an all-embracing “we.” The Pisos undergo a similar slippage. Nominally the addressees of the poem, they gradually prove to be in some ways its subject: a wealthy amateur and his two failsons in search of a writing coach—or perhaps just a cheerleader. Didactic addressees are sometimes portrayed as slow or troublesome students in need of a stern lecture. Hesiod characterizes his brother, Perses, as an idiot; Lucretius sometimes seems to show impatience with his addressee, Memmius. Ferriss-Hill reads the relationship between Horace and the Pisos as similarly fraught, his attitude to them as implicitly critical.

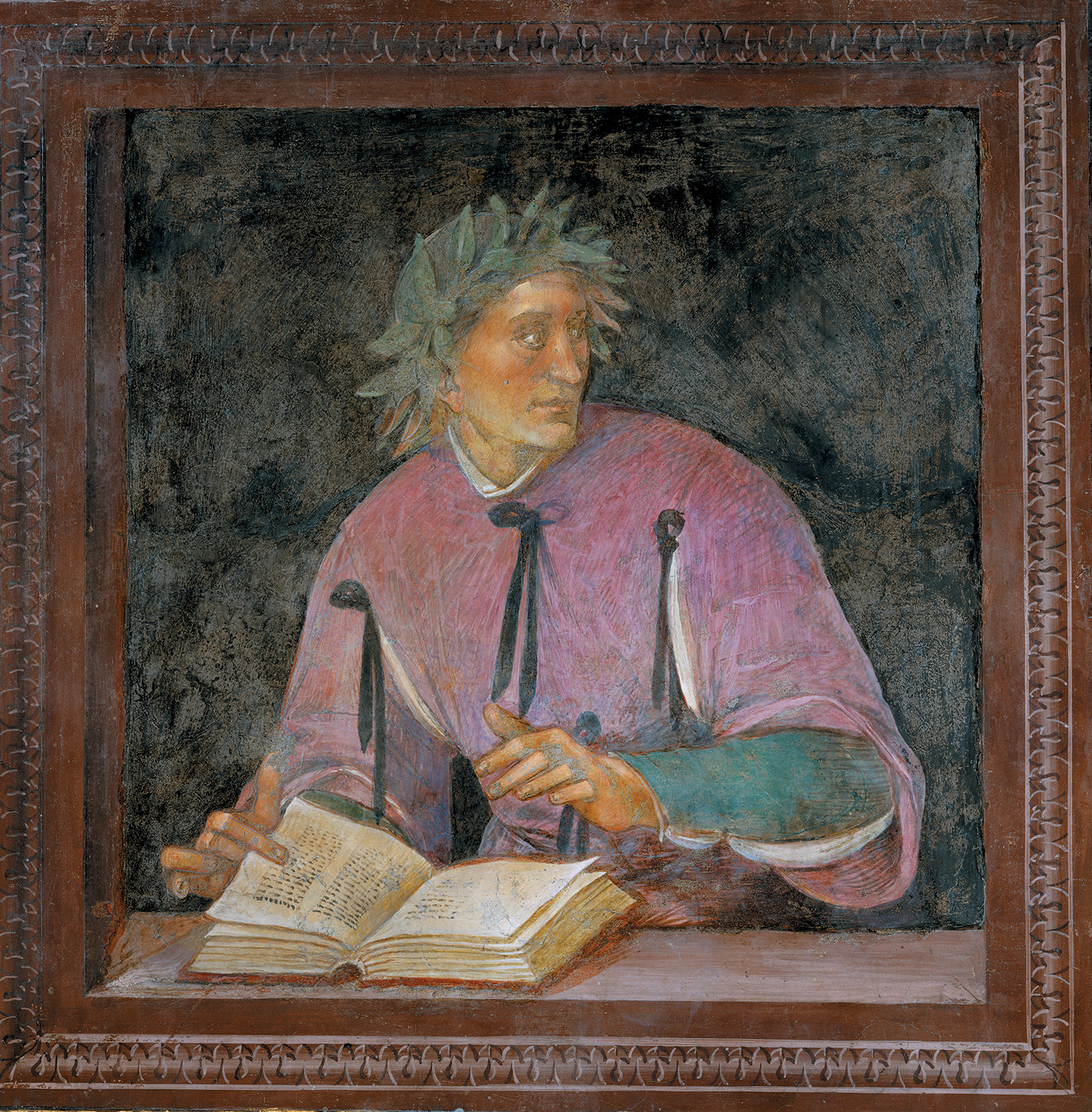

For she sees the Ars Poetica as also an essay on criticism (the title of Pope’s imitation catches something important about Horace’s original)—and not just literary criticism, either. Indeed, the famous vignette that opens the poem is a scene of assessment and critique. Suppose, says Horace, that a painter depicted a human head on a horse’s neck with feathers and a tail: “If you were admitted to view it, friends, would you be able to restrain your laughter?” On the surface the scene is there to illustrate an aesthetic principle: a work should possess organic unity (“Be a Rothko, not a Rauschenberg!”). But for Ferriss-Hill it is the final line that we should be looking at. Horace here depicts criticism as something that takes place in a social context, among friends. The image will return toward the end of the poem as the poet questions how to tell a true friend from an insincere yes-man. (Philodemus, author of the treatises “On Flattery” and “On Frank Criticism,” may be lurking here too.) The real friend, it turns out, is the one who is willing to laugh at you—and not only at your bad poetry—with a view to your improvement. And this, we might suppose, is what Horace does for the Pisos. In fact, it is what the poem itself does for them.

Didactic poets sometimes close on a darker note. Lucretius’s poem, On the Nature of Things, meant to teach us inner tranquility, concludes with a description of a devastating plague. The first book of Vergil’s Georgics closes with the image of a chariot—the Roman state—running out of control, its driver powerless to stop it. The late Greek writer Oppian’s five-book poem on fishing ends with a sponge-diver mauled to death by creatures of the deep, his colleagues grieving over his remains. And the Ars? It ends with a comic yet disturbing portrait of a mad poet, lashing out at others like a savage bear or bleeding them dry like a parasite. (“Leech” is the final word of the poem, as “human” is the first.) For the poem’s message is in the end a negative one: “Horace does not concretely help his addressees…become better poets or become poets at all because he cannot; in fact, no one can.” Poets need talent as well as training, and for those who want to write without the former, Horace’s implicit advice is, “Don’t.”

Ferriss-Hill has written a dense book, frustrating to the reader in the same way, and for much the same reasons, as the Ars itself. Her method is close reading in its most austere form: she worries at Horace’s phrasing, teases out implications, toys with alternative interpretations, follows him down blind alleys. The book loosely follows the trajectory of the poem, but it assumes knowledge of the whole: the discussion can jump forward unexpectedly, and passages we had thought we were done with will crop up again later, now viewed from a new angle or in light of new information. Readers without Latin are likely to find it hard going. Ferriss-Hill does provide an English translation facing the Latin text at the beginning of the book, though one that egregiously disobeys the poem’s own injunction not to translate word for word. When Horace discusses the coining of new words, for instance, we get:

If it is perhaps necessary

to show with recent symbols the

hidden ones of things,

it will fall to you to craft ones not

heard by the girded

Cethegi and a license taken up

prudently will be granted.

This painful woodenness is plainly deliberate; the rendering is meant solely as an aid in construing the facing Latin. Yet no reader new to Horace will emerge from the book with much sense of why he is a great poet.

What the book does do well is to document an intelligent reader’s journey through this most elusive of poems. In the process it offers us a new way of thinking about it, one in which its apparent center moves to the margins and its apparent defects become strengths. It offers a richer and more interesting Ars than most of us are used to, but one recognizably by the Horace we know from other works. Of this Horace it could be said, as Robert B. Parker wrote of Ross Macdonald, “It was not just that [he] taught us how to write; he did something more, he taught us how to read, and how to think about life, and maybe, in some small, but mattering way, how to live.”