In the parilka, the wooden steam room at the heart of every Russian banya, a stove heats a pile of stones. When the stones are red-hot, water is thrown onto them, raising billows of light steam. Reclining or standing on wooden benches, bathers sweat and whip themselves with veniki, switches of leafy twigs. When they are hot enough (or too hot), the bathers leave the parilka to cool off by plunging into rivers, ponds, barrels, or marble-tiled pools, pouring tubs of icy water over their heads, or rolling naked in the snow.

In grand urban buildings, village huts, and prison barracks; on trains, ships, and submarines; wherever Russian communities exist, the steam in the parilka has been endlessly refreshed. Over centuries, diverse cultural meanings have taken shape in this insubstantial vapor. As Ethan Pollock writes in Without the Banya We Would Perish, the banya “persisted in Russia despite radical changes in ideas about what constitutes bodily cleanliness and despite remarkable social ruptures.” With its connection to fire and ice, the banya seems to transcend history. Yet it has a history of its own, which gives “an access point to every stage of Russia’s history.”

Muscovite tsarinas gave birth in the parilka. The Romanov tsars, who came to power in the early seventeenth century, saw steam baths as a lucrative source of tax. When the westernizing tsar Peter the Great uprooted Russia’s ancient customs at the beginning of the eighteenth century, shaving off the beards of his noblemen and dressing them like Europeans, he left the banya untouched, though nothing like it existed in the West at the time. Catherine the Great built a stone banya on her estate at Tsarskoe Selo in 1779, and promoted the ancient Russian institution as vital to the health and power of her expanding empire.

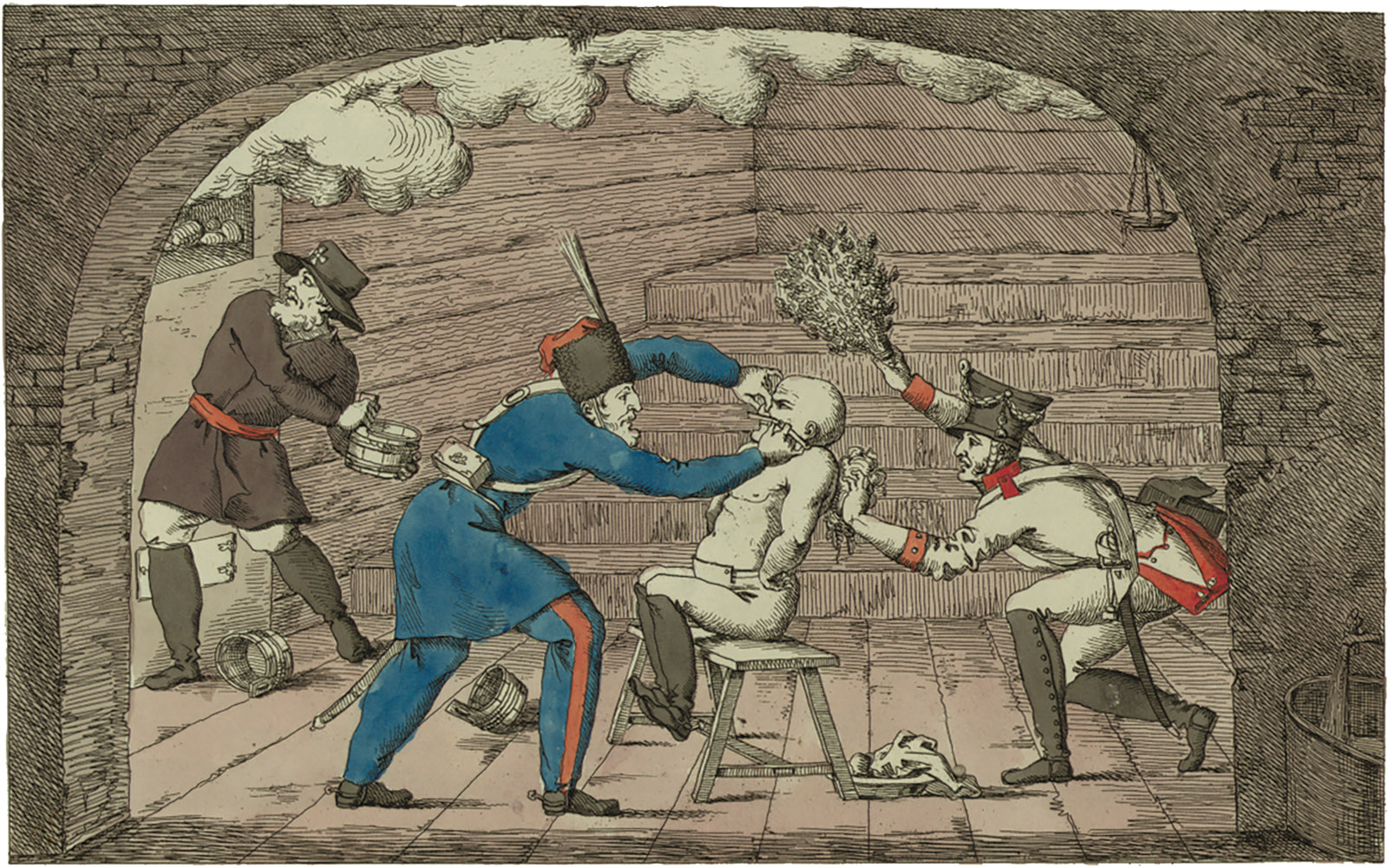

In 1812, when Napoleon invaded Russia, a popular broadside showed him in a parilka with three Russian soldiers. “I’ve never withstood such torture in my life!,” he cries, as the soldiers toss water on the stove and beat him with a venik. “They are scraping and roasting me like in Hell.” “You were the one who entered the Russian banya,” one of the soldiers reminds Napoleon, a stereotypical weedy foreigner (see illustration on page 31). A century later, when luxurious bathhouses were among the pleasures of the modern city, Grand Duke Konstantin Romanov, cousin of Nicholas II, visited the banyas of St. Petersburg for paid sex with young banshchiki (male banya workers), confiding in his diary the torments of conscience he suffered over his “great sin.” Grigory Rasputin, who became the spiritual intimate of the tsar’s family, took aristocratic women with him to the banya, to “remind them,” in his peasant presence, “of their Russian bodies and souls.”

For the Bolsheviks, the banya was a matter of public hygiene. In 1920 Vladimir Lenin lectured Leon Trotsky on the importance of banyas to the welfare of the revolutionary regime. Though there was a banya on the armored train from which Trotsky commanded the Red Army during the civil war, there were not enough in the cities and villages to slow the ravages of epidemics. A hot banya with soap and water could prevent infection and kill the lice that spread typhus. Propaganda posters explained the vector of diseases, ordering people to “go to the banya more often!” Joseph Stalin relaxed in the banya, but, as Pollock writes, the failure of the whole Stalinist project can be measured in “the woeful state of construction and upkeep of banyas” for the masses. No five-year plan could meet the people’s need for steam baths. Public health officials recommended bathing once a week, but by the end of the 1930s, there were hardly enough banyas in Moscow for monthly visits. In other cities, it was worse. Throughout the Soviet period, the chronic lack of clean, functioning banyas was one of the few subjects on which satirical criticism of state authorities was tolerated.

After Stalin’s death, his henchman Vyacheslav Molotov condemned the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev for going to a banya with the Finnish president, as though bathing with a foreigner meant capitulation to the international bourgeoisie. In the 1960s and 1970s, during the era of “stagnation” under Leonid Brezhnev, the banya was not so much a means of hygiene as, Pollock writes, “a magical space of rejuvenation and rebirth,” celebrated in popular culture. The singer Vladimir Vysotsky’s 1968 ballad “White Banya” still resonates with the lacerations of Stalinism. The song is told from the point of view of a man who has a tattoo of his lover Marinka on his right breast and a tattoo of Stalin on his left, above his heart: “Fire me up the banya, woman,/I’ll forge myself, burn myself/At the very edge of the bench,/I’ll destroy all my doubts.”

Advertisement

“The end of the Soviet Union began in a banya,” Pollock writes. In August 1991 the head of the KGB, Vladimir Kriuchkov, and a group of hard-liners from the army and the Communist Party gathered in a banya to plot a coup against Mikhail Gorbachev. A few months later, Boris Yeltsin, who led the defeat of the coup, dissolved the USSR, celebrating afterward in a banya. As a young man, Yeltsin had been made by his grandfather to build a country banya with his own hands as a rite of passage. He reminisced that it was in a banya that he realized, in 1989, that he was no longer a believing communist: “The banya, after all, purifies things…. In that moment in the banya I changed my world view.”

Vladimir Putin also grants the banya a transformative part in his own rise to power. As he tells it, he was taking a banya at his dacha with a group of friends in 1996, at a low point in his political career. As they cooled off in a nearby lake, he noticed that the dacha and banya were on fire. All that survived was an Orthodox cross, a gift from his mother, that he had removed from his neck before entering the parilka. With little but the cross salvaged from the ashes, Putin was back on course. Ten years later, the writer Vladimir Sorokin set the finale to his dystopian satire on Putin’s Russia, Day of the Oprichnik, at a grotesque all-male ritual orgy in a banya. “Great is the brotherhood of the banya,” the narrator declares, parodying centuries of nationalistic banya rhetoric. “Everyone is equal here—the right and the left, the old and the young.”

“An archaic institution of pain distributed over a diverse geographical space” is how Daniel Rancour-Laferriere describes the banya in The Slave Soul of Russia (1995). He is in a long line of foreigners for whom the banya is the symbol of an essential Russian oddness. In the fifth century BCE Herodotus traveled to lands north of the Black Sea that would one day be within the Russian empire, and saw how the Scythians threw hemp seeds onto hot stones raising a vapor that made them howl with elation and took the place of a bath. Fifteen hundred years later, the Persian traveler Ibn Rusta observed the steppe-dwellers tossing water onto hot stones and cleansing their naked bodies in the steam. In the twelfth-century Primary Chronicle, a monastic document relating the origins of Kievan Rus, another foreigner, the Apostle Andrew, is amazed by the banya when he reaches the Slavic lands:

They warm [their bathhouses] to extreme heat, they undress…take young branches and lash…themselves so violently that they barely escape alive. Then they drench themselves with cold water…they actually inflict such voluntary torture upon themselves…. They make of the act not a mere washing but a veritable torment.

As the east Slavic tribes united under the rule of the princes of Kiev, the banya became a defining feature of medieval Rus’. It combined the opulent civic bathing traditions of Greece and Rome with the wooden sweat lodges of the Vikings. Its customs were shaped by the diverse cultures converging on the trade routes between Scandinavia and Byzantium: pagan, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim. It absorbed their taboos and age-old associations of bathing with purity and defilement, sanctity and licentiousness, virtue and corruption. While the Orthodox church integrated steam bathing into its teachings and rituals (with prohibitions on mixed-sex bathing), the banya was seen in folk culture as a place for sorcery, magic, and unclean spirits.

Between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, when public bathhouses had died out in Western Christendom, where they were associated with disease and illicit sex, the banya was part of everyday life in Muscovy. In the accounts of European travelers, astonishment at public nudity, extremes of temperature, and violent flagellation with veniki became a stock motif. Queen Elizabeth I’s ambassador, Giles Fletcher, described people coming “out of their bath stoves all on a froth and fuming as hot almost as a pig at a spit…in the coldest of all the wintertime,” and leaping “stark naked” into rivers. For the seventeenth-century scholar Adam Olearius, the men and women of Muscovy bathing together “divested themselves of every trace of shame and restraint.”

“Sex trumped health when it came to travelers’ assessments of the banya,” Pollock writes. Foreign onlookers assumed that its health benefits applied only to Russians. “In the whole world there is only themselves who can bear it,” one Frenchman remarked. The eminent London doctor Jodocus Crull noted in the late seventeenth century that banyas were “universal remedies,” contributing to the longevity of Muscovites, who live healthily “for the most part without physicians,” but he was more preoccupied by the fact that women were “not very shy to be seen by men” when they bathed naked.

Advertisement

In the late eighteenth century European observers began to consider the medicinal effects of the banya. Some even crossed the threshold into the parilka. “The heat was too much for me to bear,” the French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Chappe d’Auteroche gasped. “[I] got out of the baths as soon as I could.” He had traveled from Paris to Siberia in 1761 to watch the transit of Venus across the sun. His Voyage en Sibérie, an account of the “manners and customs of the Russians,” published in 1768 with exquisite engravings by Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, was one of the most influential travel books of its time, authoritative in Enlightenment debates about Russia’s standing beside “civilized Europe.”

The banya fascinated Chappe. A natural philosopher in the spirit of Montesquieu, he viewed “Russianness” as a consequence of meteorological conditions acting on bodily fluids. “Whoever has been through one province knows all the Russians,” he assures his readers. He lists the banya as a cause of their “want of genius,” as though it were as much a part of the natural environment as a cultural institution. The “effect of the soil and the climate,” Chappe writes, makes the “nervous juice” of Russians “inspissated and sluggish,” while the “sensibility of [their] external organs” is blunted by “the flogging they constantly undergo in the baths, and the heat.” As he describes his own attempts to bathe à la russe, the assured discourse of the Enlightenment scholar becomes slapstick. In the steam, Chappe is no longer an objective observer wielding instruments of science, but a naked buffoon, giddy and panting. “The prodigious heat…seized my head,” he writes. “I…fell in an instant…my thermometer breaking to pieces.”

An admirer of female beauty, Chappe recorded manifestations of Venus among the Siberian peasantry (noting that Russian women’s looks are “gone before they are thirty” because “the baths spoil their shapes”). Le Prince’s engraving of the banya in Voyage en Sibérie (which Catherine the Great regarded as “most indecent”) depicts a rococo idyll in which naked men, women, and cherubic babies wash together. At its center, a statuesque beauty, in the contrapposto of Botticelli’s Venus, her modesty concealed by a venik, empties a tub of water over her long hair. Le Prince’s image exemplifies the ambivalence of Europeans contemplating the banya’s simultaneous suggestions of innocence and license.

A conspicuous advance in Enlightenment understanding came from the Portuguese doctor António Ribeiro Sanches, whose writings, Pollock says, had a “profound long-term impact on the way Europeans and Russians conceived of the banya.” Educated at the great medical schools of Europe, Sanches came to Russia as first doctor of the Imperial Army. He served at court and saved the life of the fourteen-year-old Princess Sophie Anhalt-Zerbst. When the princess became empress Catherine the Great, Sanches corresponded with her about the benefits of the banya. His Traité sur les bains de vapeur de Russie (1779) argued for the banya’s role in the prevention and cure of many ailments, and its importance to the state for the management of public health. After the regimen of parilka, veniki, and cold water, Sanches wrote, “the whole body will feel easy, fresh and the soul will also lighten. The banya is the great healer.”

It took over a century for medical science to catch up. Russian doctors were among the last to concede that an indigenous practice so long regarded as backward could be at the forefront of European prophylactic medicine. By the late nineteenth century, when germ theory showed that microscopic organisms causing infectious illnesses lived on skin, bathing was generally acknowledged as a public good. In the wider culture, the banya was by now revered for its ancient origins, seen as a “uniquely Russian social space” untainted by the West, reflecting the intuitive wisdom and authenticity of the people. The banya’s “origins are synchronous with the origins of Russian history,” one doctor wrote in 1888; “it is directly connected with the conception of ‘Russian.’” Peasant sayings like “the banya steams, the banya cures” and “without the banya we would perish” were endorsed by the Brockhaus and Efron encyclopedia in 1891, which listed scores of ailments that the banya could treat, from catarrhal illnesses to neurosis and heart disease.

Late-imperial Russia was a golden age for the urban banya. Innovation came from commercial proprietors rather than doctors or the state. Establishments like the Egorov banya in St. Petersburg and the Sanduny in Moscow were as much about sociability and relaxation as health. Typically, banyas had four sections with ascending levels of comfort and amenity. The luxurious sections were fitted out with leather couches, chandeliers, tiled washrooms, gilded mirrors, and swimming pools. Banshchiki provided a range of services: cleaning, hauling fuel, tending the steam, flogging bathers with veniki, and selling food and drink (and sometimes sex, “for a few rubles and some beer”).

“Not a single Muscovite abstained…not a master of trade, not an aristocrat, not a poor man, not a rich man could live without the commercial banya,” wrote Vladimir Gilyarovsky, a chronicler of city life. In the 1880s Anton Chekhov published two vignettes called “In the Banya,” in which naked mingling in the steam gives rise to comic muddling of social identities. In his essay of 1899, “On Writers and Writing,” the mystical nationalist writer Vasily Rozanov quoted the Primary Chronicle, hailing the banya as a thousand-year-long “stream of human contact,” “a wonderful world,” more ancient and democratic than the English constitution. As Pollock writes, he “welcomed the banya’s associations with sex, extreme heat, and beatings that so shocked foreign observers.”

In 1906 Mikhail Kuzmin’s novella Wings unveiled the banya’s homosexual subculture. For the Hellenist Kuzmin (unlike Grand Duke Konstantin), this aspect of the banya was an unashamed harking back to ancient Greece, but despite the aesthetic refinement of Wings, it was labeled pornographic. The photojournalist Karl Bulla’s pictures of the interior of the men’s washroom in St. Petersburg’s Egorov banya “almost dared his viewers not to see sex,” Pollock writes. His photographs are like tableaux vivants: frozen in their ablutions, men and boys lie on marble benches, stand under showers, and hold veniki over each other’s naked bodies.

Representations of women bathing are a perennial fascination of male fantasy in visual art, and, at least since Le Prince’s engravings for Chappe’s Voyage en Sibérie, the banya has been an ideal subject. The painter Firs Zhuravlev imitated European depictions of languid odalisques with flirtatious eyes in his 1885 canvas Bridal Shower in the Banya. Zinaida Serebriakova sensationally disrupted these traditions in her 1913 painting The Banya. The powerful bodies and open faces of her bathing women convey, Pollock writes, “indifference…rather than allure.” Soviet paintings, from Boris Kustodiev’s Russian Venus (1926; see illustration on page 30) to the 1950s works of Socialist Realist painters Alexander Gerasimov and Arkady Plastov, confirmed the female nude in the banya as a timeless symbol of Russian wholesomeness: radiant flesh and long blond hair in a haze of steam against a backdrop of wood and wet birch leaves.

Rare glimpses into women’s experience of the banya, meanwhile, convey the profound contentment to be found out of sight of men. The Russian-Scottish writer Eugenie Fraser remembers the “happy orgy of splashing” as she bathed in a late-imperial banya with her mother, nanny, and grandmother, who lay on the highest shelf in the parilka with a cold cloth on her forehead. In the women’s section of Moscow’s Sanduny in the late 1970s, the American novelist Andrea Lee enjoyed the “magical freedom…of women in a place from which men are excluded.” Among the “unpretentious and unself-conscious” women at the banya—women she had seen “carrying string bags on the metro”—Lee identified a “wholesomeness” that she found “characteristically Russian.”

Like all cultural rituals of purity and impurity, the rituals of the banya create unity in experience across time. In both tsarist and Soviet times, the banya could be a space of redemptive happiness, cleanliness, and freedom, or it could be hell. The aristocratic narrator of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the House of the Dead is horrified by a prison bathhouse: “Steam blinds your eyes; there’s soot, dirt, and human flesh packed together so densely.” Similar images echo in the testaments of the Soviet Gulag by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Varlam Shalamov, and others, for whom the labor camp banya was a place of filth, degradation, and violence. In the Gulag banya there was “no limit to bullying” and “no limit to human endurance,” one survivor remembers.

In the late Soviet period, the country banya resurfaced as a cultural ideal. By then, despite the efforts of the Banya-Laundry Administration and generations of Communist planners (whose activities Pollock recounts with a weight of statistical detail mined from the archives of municipal bureaucracies), banyas in the cities were often dilapidated, squalid, and scarce. In literature and film, the rural banya, “a space conducive to contemplation and potential redemption,” came to embody authentic Russian tradition. In Vasily Shukshin’s story “Alyosha at Large,” the peasant Alyosha steadfastly devotes his Saturdays to the slow rituals of the banya, true to the rural ideal in the face of modernization. In Nikita Mikhalkov’s 1980 film A Few Days from the Life of I.I. Oblomov, the rural banya makes a natural setting for soulful conversation between friends, conducive to “vigor and idleness all at once.” The urban banya was the ideal space for a different kind of male friendship, offering alcohol and freedom from domesticity. In The Irony of Fate or Enjoy Your Steam, one of the most popular Russian or Soviet films ever made, the steam conjures a beneficial transformation in the life of the hero, Zhenia.

The volatility of the post-Soviet period accentuated the banya’s power to heal and transform, “to set things right,” as Pollock writes: “The more the culture changed, the more the banya accrued value as something that was ancient and consistent.” As contemporary Russia revels in national traditions, the banya is still accruing value. The Sanduny, which preserves the grandeur of late-imperial Moscow, now sells its own brands of vodka and honey, with an oak leaf on the label. Yet expert banshchiki still tend the steam, bathers still pay to be thrashed with fragrant veniki, and nakedness still feels wholesome.

Pollock tells the long story of the banya in chronological order, exploring countless nuances of social reality and artistic representation, gathering its recurring themes. But he begins and ends his book in the present tense, naked in the parilka. In his prologue, Pollock is bathing with Russian friends in 1991, “as the Soviet Union collapsed and a new Russia emerged.” In the whimsical epilogue, Pollock immerses himself in the illusion of the banya’s timelessness. His friends are transformed, in his daydream, into the many historical figures, writers, and fictional characters invoked in the pages in between, all bathing with him in the parilka. The lightness of the steam overcomes the weight of history, and culture is timeless. “I feel relaxed and alive,” Pollock writes, “washed clean enough to imagine that the banya has no beginning and, so long as there is Russia, that the banya will have no end.”